Today makes twenty—a surreal amount of time since you left. Several eternities. You would most likely be bald by now, Carey, maybe even a little paunchy if my thirst for childhood revenge had a say.

Twenty years does a lot to any family. And we are no different. I think you would still recognize us—genetics is relentless—but then you knew that best of all, with your fancy degrees and everything. We’ve quadrupled in numbers now between spouses and kids. Six nieces and nephews, all unique and amazing: actors, dancers, astrologers, even Olympic-bound athletes. They are strong and resilient kids who know all about you, have never stopped hearing about you. When they are together it’s like a barely controlled nuclear experiment. And it always ends in us gathering around them as they put on a show. Doesn’t matter when: Passover, Rosh Hashana, or Sunday brunch. You are always there, too. We never stop thinking about you. How you would have laughed your ass off at their weirdness. How much they would remind you of us as kids. And how your own kids would have contributed.

It was barely two weeks after you left us that Sharon and I found out we were going to be parents, and shortly after that suffered the first of two tragic disappointments. Needless to say Sharon’s pregnancy was fraught with anxiety. It was obvious to me, if not to anyone else, that fate or God or whatever was using us as a punching bag. When our beautiful boy finally did make his way out, he was days late and arrrived by emergency C-section. Even our moments of joy didn’t come easily. But at least they came. And that baby seemed to edge open the clouds and let a little light shine down on this beaten group. It didn’t take us long to name him Carey, after you.

Our Carey is going to be eighteen this year. He is more curious about you than ever. I wonder what it must be like for him to wear your name around people who remember you and what the name used to mean and what it still does. He has never questioned it or dismissed it, which would have been an easy thing to do. Maybe he wouldn’t want to be named after the uncle who killed himself. But the family never treated it that way. If anything, we probably deified you a bit too much. Put you on a pedestal. Twenty years can make your memory very selective, which gives us the luxury of reinterpreting history. It’s probably why, for better or for worse, he wears your name like a badge of honour.

Mom and Dad are twenty years older, too. There was a time at the beginning that I didn’t know what was going to happen to them. You don’t bury a child and stay the same. Dad was the one who called me after they found you. I was at work, and he just kept screaming into the phone that you were dead. Over and over. My boss threw me in a car and drove me to Dad’s place to try to keep him together. But I couldn’t do it. It seems none of us could, no matter how hard we tried. Dad nearly gave up on everything, including us. Still, it feels like he doesn’t want real relationships with anyone. People die after all. Even your kids. He moved far away from all of us, which was fine until he became chronically ill and required care. He is difficult, Carey, maybe more for me than anyone else, but still. We miss your input on this one.

The first time I saw Mom after they found you was when she came back from identifying your body. She was so calm and quiet. Unsettlingly eerie. I was expecting hysterics but there wasn’t any. She surrounded herself with your friends and insisted on them telling and retelling tales of your wicked sense of humour and odd stunts. No boundaries. Everything was fair game. Underage drinking. Weed. She didn’t care. She just wanted to hear about you.

I think now, for the most part, she is happy. She seems to be as well adjusted to “the new normal” as much as she can be twenty years later. That’s what she calls it: one day she could be normal again, even if it wasn’t the same normal as before. Either way, she seems to be at her absolute happiest when surrounded by all her grandkids. Manic, almost. But the truth probably isn’t as optimistic as that. All of her moments of joy—all of them—are bittersweet. They are edged with pain, with loss, and with your absence. They always will be. That is her normal now.

As for me and your other siblings, well, I guess the reality is that we are different people now, for better or for worse. We own homes and cars and vacation properties. We each have amazing spouses who love us, and children who fill us up with all the blissful crazy we can take. We are okay. We made it. But goddammit, Carey, we miss you. We’ve been clinging to each other for the past twenty years—probably a little tighter and a little more desperately than most siblings do. We took a bullet. It really feels like we did. It may be all scarred over now, but it’s still there. You don’t even have to look that close. And when the three of us are together, with love and intensity and joy, there is still no escaping the empty space. It’s supposed to be four of us, Carey, not three. Four. Not three. Four with the same DNA, with the same parents, the same shared history. You cannot heal a vacuum. It’s just a vacuum. Forever.

Twenty years has brought me relatively safe to shore. I am so grateful for that. But I was bad there for a while, Carey. It was a difficult road. I was angry, really angry, at a lot of different things. The injustice of how such a brilliant mind was so infected with pain that it couldn’t stand another moment on Earth. How I couldn’t seem to help no matter what I did, and how I eventually gave up on you. But mostly I was angry at how I didn’t get to say what needed to be said between us. The things that mattered.

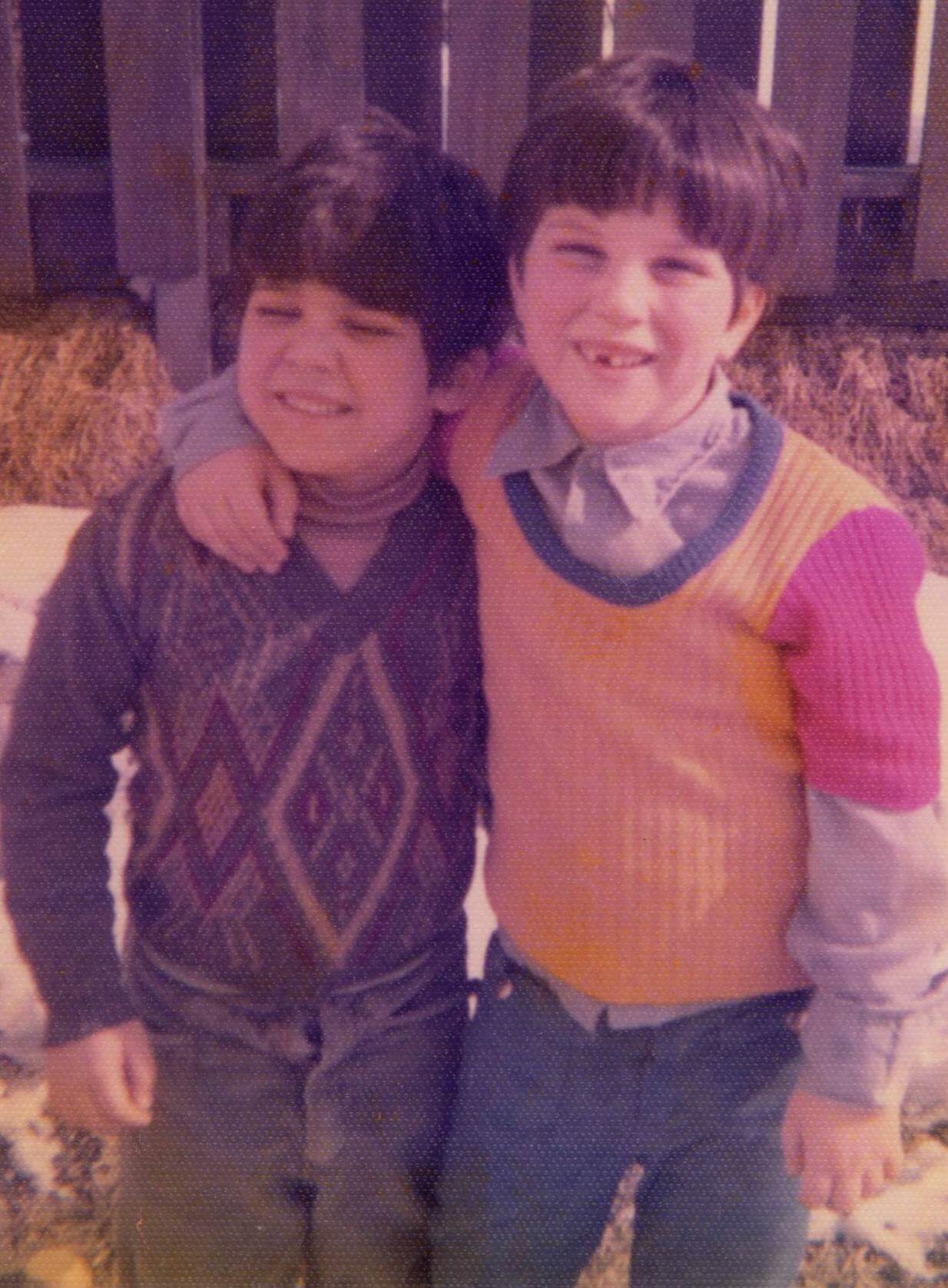

I was less than two years older than you, and we wouldn’t leave each other alone. We drove Mom past her limit. We literally beat the shit out of each other for the first fifteen years. You never let me forget that I was fat and I never let you forget that you were inexplicably strange. There was bloodshed and weaponry. But somehow we lived through it and turned the corner. We even moved in together after Mom and Dad broke up. We had a meeting of the minds.

But your illness was already at work. You wouldn’t sleep. Late at night I would wake to hear you softly crying in the bedroom next to mine, but I didn’t dare ask what was going on. You were intensely protective of your privacy. And then you started disappearing for days at a time. So I asked you why and you told me. It was hard for me to understand your hospital stays. Mental illness didn’t make sense to me at the time, and I needed, I still need, things to make sense. The worse you got, the less I understood. When we had to start pulling you off bridges I just got angrier and angrier with you. Why couldn’t you help yourself? Why weren’t you letting us help you? Why were you endlessly dragging us out in the middle of the night to save you when you obviously didn’t want to be saved? Why were you doing this to us?

And then you did it. And I was relieved it was over. Actually relieved.

How horrible a person are you to be relieved that your brother is dead? That was me. I will always have this weight. I will go to my own grave with it. You deserved so much better than me, Carey. I was the worst example of a brother, while you were alive and when you weren’t. I should have done everything differently. I desperately wish I could change that, and I wish you were here so I could tell you that to your face. But I get it now. I understand. All of it. The depression. The loneliness. The absence of hope. I know the illness very well now. It has taken me twenty years to get here, but I have forgiven myself. Because you aren’t here to forgive me.

Twenty years ago you made a grave miscalculation in your exit from this world. You sincerely thought we’d get past it and move on. You even wrote it in your notes. Well, we failed you miserably. We moved on, but we never got past it. Sometimes I think I miss you more now than ever before.

We were so young back then, Carey. I’m nearly fifty, and you would have been right behind me. My kids were all born after you died and suddenly they are graduating high school. I wish I could explain to you how impossibly fast this time has gone. We have all grown older and wiser. But no one ever got past it.

Quite the opposite.