It starts the way a dream might start: I’m in a boat riding down a canal inside a shopping mall that is also somehow Venice, and Céline Dion is my gondolier. Her voice is right there, singing just for me. “Take me back into the arms I love,” she begins, so close it’s more like temperature than sound.

This gondola is made for love. It carries passengers in units of two, or two and two plus the gondolier makes five, which happens to be Céline Dion’s lucky number. I’m riding alone, balanced in what isn’t so much a seat as a place to cuddle up, press knees, hold hands. “Just believe in me, I will make you see all the things that your heart needs to know,” Céline reminds me, romantic as hell.

We pass under a bridge and the key changes, the song gliding up to meet its own bridge. The word for what’s happening is coincidence. Céline lets her voice open all the way up, reaching out to caress every stone: “Whatever it takes, we’ll find a waaaaaaaay—”

We emerge into the light, and the singing is cut short. Dream over: I’m in Las Vegas, being ferried on a twelve-minute journey up and down the Grand Canal Shoppes of the Venetian, which is an almost-pretty thing to call a mall. For the remainder of the ride, my gondolier, who moonlights as a Céline Dion impersonator, slips back into character, and we pretend to pretend that we’re in the real Venice. It’s only kind of a stretch—the boat is real, and the canal is really man made, like all canals are. My gondolier, clad in a navy-striped T-shirt, straw hat, and red satin neckerchief and sash, serenades me with an old Italian folk song as we glide past an Auntie Anne’s pretzel shop and a store called Socks & Bottoms.

The mall’s ceiling is a trompe l’oeil mural of the sky, and I find myself checking to be sure it isn’t a screen projecting a moving image. It’s only paint, but the light is warm, and without thinking, I close my eyes and dial my face upward like a starved Canadian heliotrope searching for vitamin D and happiness. For a moment, I give myself to the illusion and tell myself it’s just like the real thing.

Céline Dion has been in residence at Caesars Palace Las Vegas more often than not since 2003. They built the Colosseum just for her, plugging 95 million American dollars into a 4,000-plus-seat concert hall modelled after the ancient Roman original, though this one has the largest LED screen in North America and a stage that’s more motorized lifts than stable ground.

The gamble has paid off. Céline Dion’s first occupation of Caesars, A New Day…, is the highest grossing concert residency anywhere, ever, with Billboard reporting that it earned the equivalent of $610 million Canadian during its run, from 2003 to 2007. Queen Céline returned to her palace in 2011 for Céline, which is the second-most successful residency in history, having taken in $320 million by the time it ended in June of this year.

Céline’s time in the desert has been epic. I mean that in the classical sense: lengthy, episodic, featuring the triumphs of a heroine. Over the past sixteen years, she has performed in Vegas 1,141 times. That’s around 1,141 days of total vocal rest to save herself for the show, 1,141 times yelling, “Shall we go for it?” at the audience, 1,141 E-flat-fives belted at full volume while doing the kind of Gumby-like back bend a yoga teacher would call a heart opener. Céline—is it okay if I call her Céline?—has opened her whole bleeding heart to 4.5 million people in Vegas alone.

Back in 2003, the Vegas strip was a palliative-care ward for fame: residency there was little more than a way to let one’s star fade with a little dignity, plus 24/7 access to slots and steaks. Then came Céline—still Titanic-ally famous, her heart going on and on—and soon others followed. First Elton, then Britney and J-Lo and Shania, and now the fresh class of Vegas residents includes Lady Gaga, Cardi B, and Drake. Céline Dion—who has long been impressive and spectacular but until recently few would have called cool—made having a Vegas residency a Thing.

At fifty-one, Céline has arguably become Canada’s greatest living icon. Parents love her, grandparents adore her, and now the younger generation is discovering that not only is she endlessly talented but also endlessly memeable. The internet swooned when she arrived at this year’s Met gala looking like she’d been baptized in gold paint and sewn into a bodysuit slash bead curtain, a corona of singed peacock feathers growing straight out of her skull. Not long after, she sashayed through Paris Couture week and Twitter feeds like a living gif, serving such high-meets-low looks as a no-pants-no-problem scuba number with blazer, a gown that looked like sound waves rendered in mesh, and a replica of the honking Titanic jewel necklace worn over an “I Love Paris Hilton” T-shirt.

At the apex of midlife, here’s where things are at for Céline: It’s been three years since René Angélil, her manager of more than thirty years and husband of twenty-one, died of complications from throat cancer. Her twins are eight years old; her eldest son recently became an adult. In April, she signed her first beauty contract with L’Oréal Paris. Her new gender-neutral children’s clothing line, Célinununu, is popular with both shoppers and conspiracy theorists (think onesies that manage to be both cute and somehow satanic). This September, she launches Courage, her first world tour in over a decade, kicking off the first sixty-six dates with close-to-home concerts in Quebec City, Montreal, and Ottawa. Her twelfth studio album in English and twenty-seventh overall—also Courage—is expected to drop in November. Not one but two Céline-inspired biopics are currently in production.

As she leaves Vegas and heads back into the world, nearly four decades into her career, a full-blown Célinaissance has been declared. But why is her celebrity suddenly so pressing, so meaningful, so of this moment? Céline isn’t exactly new—just about everyone already knows the basic story: born and raised outside Montreal, a preteen singing sensation by fourteen. More than 200 million album sales later, she’s banked five Grammys, two Oscars, seven Billboard Music Awards, twenty Junos. She’s been around for so long that much of the world has no conscious memory from the Before Céline era: she has always been the soundtrack to grocery store aisles, cab rides, the corniest parts of every cornball movie you hate to love.

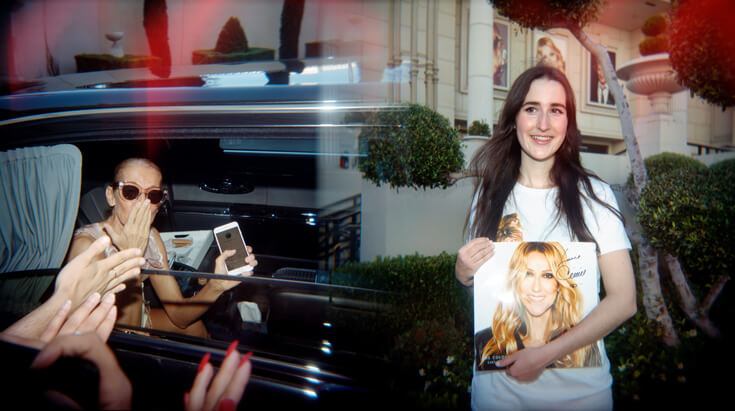

Trying to understand Céline’s resurgence after a lifetime of fame feels like trying to pinpoint when exactly weather becomes climate. I decided to get closer to the source. I went to Las Vegas see Céline Dion in the final days of her Céline concert. But I also went to see her in not-Céline—Vegas being a breeding ground for impersonators who have made embodying the icon into their art and their livelihood. After all, celebrity can be blinding—sometimes the best way to see it is to turn away from the bright centre of the many-sequined spectacle, to reconstruct the disco ball by looking at the carousel of lights spinning in its orbit.

Morgane Latouche started out as a dancer: first in ballet, then doing cancan at a Paris cabaret before moving to the US nine years ago and getting a part in the Vegas showgirl classic Jubilee! As she entered her thirties, years of kick lines and falling into the splits were taking a toll on her body. Latouche needed a retirement plan, so in 2014, she started taking vocal lessons. All she wanted to learn were Céline Dion songs. Her vocal coach, who happens to be a Madonna tribute artist, was the first one to see it: she thought Latouche might have what it takes to pull off a Céline impersonation.

“I was like, Me? No way! There’s no way I can do what she does, no. She’s, like, up there,” says Latouche in an accent that is French-French, not Céline-French, holding her hand far above her head to show me where exactly Céline Dion exists. It seemed like hubris for a brand-new vocalist to think she could replicate the three-octave diva’s rare power. “I had people who had been singing for twenty, twenty-five years tell me, ‘Pffft, Céline. Well, good luck.’”

But then Latouche thought, Why not, as she puts it, “Go for the big one”? She’d loved Céline since she was thirteen and first heard 1995’s D’eux, which remains the world’s bestselling French-language album. Latouche says: “It came from a place of passion, not a place of ‘I wanna make money out of it,’ or for my ego, or ‘I wanna be the best.’ No, it came from just happiness that I was able to sing like her. That’s just happy!” So she put together a wardrobe of glittery dresses and began taking gigs—unpaid, at first—at retirement homes, fundraisers, wherever she could.

When she was starting out, Latouche would overwork the performance, trying too hard to match every step and gesture and note to one of Céline’s. Now that she’s been at it for a few years, she’s reached an equilibrium where she can tell herself: “You sound enough like her, you look enough like her, so just be her but, like, chill about it,” she says. “Only now I feel her even more in me. It just comes naturally. It’s not forced anymore. I feel like I tap into something. And I know that I channel something about her.”

Latouche wants to be clear: she doesn’t mean channel in a formal sense. She isn’t psychic or anything. But she does believe in trusting the universe. She calls vibes “vibrations” and tells me that you can be with a person “vibrationally” even after they’re gone—or even if, like Céline, they’ve never exactly been with you to begin with.

When she sings, she feels it: a frequency of Céline-ness riding on the air, like some aspect of the real deal is making itself felt through her. “It’s a weird feeling—a good feeling. So good. I feel like I’m just with her,” she says. “You know that mother-daughter kind of thing? I know it’s weird, but I feel protected, in a way. Like I have validation and a motherlike sensation of protection.”

Latouche, who is now thirty-seven, reminds me of Céline a lot, actually: charming, warm, toggling so suddenly between goofiness and earnestness it’s almost disconcerting. She recently became a mom, and she tells me it’s brought up all these small points of intersection between her life and Céline’s. Latouche’s mother is named Thérèse, same as Céline’s. Latouche gave birth to her son by C-section, just like Céline did for her twins. When Latouche and her fiancé had their son baptized at a Vegas cathedral, the priest told them afterwards that he’d organized the christening of Céline and René’s twins. “All the time, it’s always like that,” Latouche says, “another event that’s bringing me so close to her.”

It’s not that Latouche thinks the coincidences are prophetic, exactly; she knows she might never meet Céline Dion, might never get any closer to her than she already is. But the details feel important—haunting, in a good way.“She must know who I am. She must know,” Latouche muses at one point during our conversation—but, like, she’s musing intensely, musing kind of hard. I find myself agreeing, saying yes, of course she must, thinking, How could Céline miss this? How could she not feel it, you know, vibrationally?

Back at my hotel room, though, I’m not so sure. I try to imagine Céline Dion googling herself, picture her typing “Céline Dion impersonator” into a search bar. Does Céline really need to go looking for herself in the world? Does she ask the whole stupid internet the same questions the rest of us ask: How do you see me? Who am I really?

René Angélil loved to gamble. He was capable of yo-yoeing through losses and gains of up to a quarter million dollars in a year. But the biggest bet he ever took was on Céline herself, mortgaging his home to pay for her first album, 1981’s La voix du bon Dieu. Angélil held to what he called a “theory of patterns,” claiming that wins come in waves. He believed you can tune in to the vicissitudes of fortune, feel when luck has gathered around you and when it’s left you on your own.

Céline is similarly attuned to the vibrations of chance. Take five: it’s been her lucky number for thirty-seven years. She was fifth to perform at the 1982 Yamaha World Popular Song Festival in Japan twice in a row, drawing the same lot for the final rounds of the competition. Then, as she stepped onstage, she spotted a five-yen coin and slipped it in her shoe. The Japanese word for five is go. Céline went. She won.

“You don’t create superstitions, it happens,” Céline once told a reporter who was not me. Her world is full of rituals, tokens, and charms. When events feel important, Céline circles back, repeats, willing moments to overlap like a double exposure. Her assistants once happened to wave goodbye to her in unison, so now they have to do it that way every time. She does a thumb-forward handshake with each member of her crew before a show. She found a nickel onstage in Trois-Rivières, like the Japanese coin resurfaced in a new form, and now it lives in her Louis Vuitton purse.

LV: Louis Vuitton, Las Vegas, the Roman numeral for fifty-five. The initials LV held some special meaning to Céline and Angélil that was none of these or all of them—Céline swears she’ll never tell. The pair had a secret handshake, dancing their fingers at each other like baseball coaches signalling a play. Before a show, she would lay the fingers of her right hand on his left and hold them there until they both felt it: connection. Now she does it before every show with an effigy—a literal replica of Angélil’s hand, cast in bronze.

Steven Wayne has been performing as Céline in Vegas for longer than Céline has. In 1999, he was working as a kindergarten teacher in North Carolina when a producer called to say that the long-running Vegas drag revue An Evening at La Cage had lost its Cher and was looking for a replacement. Coincidentally, Cher was Wayne’s drag specialty. The only catch was they needed someone who could do double duty as Céline Dion. Wayne sort of knew who that was. He went for it.

“I called the producer and I flat-out lied,” Wayne tells me. “I said, ‘I am a Céline Dion lookalike.’” Then, in an era before YouTube or the verb “to google,” he pored over his copy of VH1 Divas Live on VHS, grabbed a blond wig, and went west.

Wayne played Céline and Cher in La Cage twice a night, six nights a week, for ten years. “The joke was you needed a note from a mortician to get off work,” he says. In 2009, a version of the show was remounted as Frank Marino’s Divas Las Vegas, and Wayne put in another nine years as Céline slash Cher right across the street from the real Céline at Caesars Palace.

“It was my dream job,” Wayne tells me, speaking in the past tense because Divas closed abruptly last summer over a case of fraud (Marino wasn’t so much donating a share of proceeds, as advertised, as not doing that). Since then, Wayne—who is still a full-time kindergarten teacher, by the way—has been setting up gigs for himself, going it alone.

He hates to admit it, but when he first started playing her, Wayne didn’t think Céline was very, well, attractive. Plus the audience would always laugh when he played her. It wasn’t about Wayne: even at the peak of her stardom, Céline has always been just a little bit marginal, a little bit ridiculous, the butt of some long-running, unspecified joke. In time, Wayne says, he came to realize that the laughs weren’t at his expense—they were a form of appreciation. “I had to understand that that’s how they were letting me know they recognized what I was doing,” he says. “They understood the connection.”

Steven Wayne and Céline Dion are the same age, born within a few months of each other in 1968. She may not have been his first choice for a celebrity to embody, but after so many years, his attachment has grown deep. “She’s had a total metamorphosis—caterpillar to butterfly. She came to Vegas and turned into this goddess. I think she’s just breathtaking,” he says. He will sometimes plug “Céline Dion live” into YouTube and just let clips run in the background all day, spending ambient time with her while he tends to his wigs. (He has many for Cher—1960s-long and black, platinum waves, mop of dark ringlets curled individually by hand—and one perfect honey-blond blowout for Céline.)

“Cher was my original passion,” he says. “But I have more fun being Céline, because I get to just act like a fool.” He does a small, controlled spasm to demonstrate, and even though right now he’s a medium-aged, medium-sized man in glasses and a Superman T-shirt (it was superhero day for the kindergarteners), I see it—she’s right there. “She possesses my body,” he says. “It’s like I’m Canadian all of a sudden.”

I ask if he’ll still be performing as Céline when they’re both eighty-five, and Wayne says absolutely, yes, he’s in it for life. “People are like, ‘Are you saving for retirement?’ I’m like, ‘No, I’m saving for a facelift. I’m not going to retire.’” He has a feeling Céline is the same, the kind who lives for her work. He imagines her future: chart-topping albums, world tours, a triumphant return to Vegas someday. He hopes to see her fall in love again. “I mean, she’s young,” Wayne says. “I like to think that I’m young too.”

A scene that seems apocryphal, even though it’s true: twelve-year-old Céline Marie Claudette Dion of Charlemagne, youngest of fourteen children, beloved but accidental coda to her warm, musical family, stands in René Angélil’s office, sings a capella, and brings the Québécois music mogul to tears. The song she belts into a pen, “Ce n’était qu’un rêve,” (“It Was Only a Dream”) was written by her mother and brother, designed as a vehicle to carry young Céline’s voice into the heart and tear ducts of someone like Angélil, someone with the power to make a star.

“Ce n’était qu’un rêve” is like a musical adaptation of a 1990s Lisa Frank lunchbox: a story of an enchanted garden overrun with winged horses and pastel butterflies, fairies and flowers and doves. “Though just a dream / so beautiful, more real than I can say,” goes the English version of the chorus. The song would become Céline’s first single, charting in the top ten in Quebec.

In the years since, Céline’s song choices have remained just as melodramatic and saccharine. But her vocal skill is no joke. Within the music industry, she’s earned an eclectic roster of fans: Alice Cooper, Ice-T, Pavarotti, Prince. Drake says his next tattoo will be of her face. She is discussed with the same reverence as Whitney Houston and Mariah Carey, and only a handful of singers alive can match the horsepower she brings to her full range. As critic Carl Wilson points out in Let’s Talk About Love, his 2007 book on Céline’s place in the pantheon of taste, the force of her talent is most often delivered as a statement of fact: those are some pipes.

Brigitte Valdez was the first Céline hired by Legends in Concert, an impersonator revue and the longest-running show in Vegas. She got the audition thanks to an Elvis she met on a briefly lived impersonator reality TV show.

When she started at Legends back in 2002, Valdez was still a relatively new Céline. The vocals came to her easily enough, but she struggled with the speech and the look. Her mom, who is part French, helped Valdez with the accent, but Legends didn’t have in-house costumes or makeup artists for main acts. “You’re kind of thrown to the wolves in that way,” Valdez says. She sourced hair and makeup advice from a drag queen who was about to leave the part of Cher with a side of Céline at An Evening at La Cage.

Valdez did not start out planning to impersonate Céline Dion; she was tapped by an agent who heard her sing with a cover band. “I never in a million years would have ever pictured myself as an impersonator or a tribute artist,” she says. “I guess it was a gift that was given to me.”

But performing took a toll. She doesn’t play Céline as often as she used to; when she stopped performing regularly with Legends, in 2007, to have kids, she decided to put the six-show-a-week days behind her. “It just takes a lot. I mean, not only physical energy and work but the emotional that goes along with it,” she says.

When René Angélil died in January 2016, Valdez had to perform as Céline soon after she got the news. She couldn’t make it through rehearsals without breaking down. There she was, all dressed up in her white satin suit and blond wig, her makeup in place, and she couldn’t keep it together. “I would literally start crying in the middle of the song. I was like, How am I going to get through the show this way?” she says, sighing. “You just take it so personally when you’ve been doing a character for so long.”

In 1990, three nights into the tour for Unison, her first studio album in English, Céline Dion lost her voice. Singing onstage in Sherbrooke, Quebec, it just “came apart like wet paper. It was like entering a vacuum,” she writes in her 2000 autobiography, My Story, My Dream.

Céline was only twenty-two at the time, and her response to her vocal injury was extreme, beginning with a weeks-long retreat into total silence followed by the razing and reconstructing of all her natural vocal habits, building new muscle memory from scratch. For the nearly thirty years since, she has been following almost unfathomable physical, vocal, and dare-I-say spiritual regimens: vigilant exercises, special diets, a lifelong relationship with speechlessness. It’s a strange combination of self-denial and self-worship—treating her body, with all its temporary, mortal vicissitudes, as a vessel for her voice. Céline manages to even make asceticism seem extravagant.

This is Céline’s default setting: over the top, excessive, too much. She wears her heart on her sleeve but makes it fashion. Consider her blowout royal-style wedding at the Notre-Dame Basilica in Montreal (public procession, live TV broadcast, Céline sporting a headpiece so burdened with crystals that she told her hairdresser to pin it straight onto her scalp) followed just six years later by an equally ostentatious vow renewal at Caesars Palace (pan–Middle Eastern themed, camels, René playing the part of a caliph, Céline as Scheherazade). “Wealth doesn’t hide itself,” she writes in her autobiography, shrugging off critics. This is a woman who owns so many pairs of shoes (possibly as many as 10,000, she isn’t sure) that she had to acquire a warehouse to store them all.

Laura Landauer looks a lot like Céline Dion. Maybe not in a stop-for-an-autograph way, but from the right angle, the resemblance is more than passing. And Landauer knows her angles: how to pull her face like taffy, how to fling a rangy limb just right. She now lives in Toronto but was born and raised in Montreal, which I suspect brings something incalculable to her version of Céline—a shared terroir.

Despite these natural advantages, Landauer actually started out as an Elvis, encouraged slash dared by a friend who happened to be an impersonator of the King. Then she dabbled in Cher for a while before finding her way to Céline. In 2007, she put on a one-woman play called Céline Speaks; the following year, her sketch video “The Celine Dion Workout” went quasi-viral, and she was tapped for a role as Céline in the Mike Myers film The Love Guru. More than a decade later, Landauer still gets regular work as a Céline. She says the requests tend to ebb and flow. She has no idea why. She’d fielded about ten queries the month we spoke.

An impersonation, Landauer says, starts with watching and listening: videos, music, interviews, anything you can get your hands on. You don’t just study the person; you need to spend time with them ambiently. Then, when it’s time to perform, you take a breath and just go for it. Like, literally: “You just kind of breathe them in,” Landauer explains.

For years, Landauer put herself through a Céline-immersion program where hers was the only music she would listen to. She doesn’t need to do that anymore; Céline is now muscle memory. “Sometimes, my kids will be like, ‘Um, stop it, you’re saying that word like Céline,’” she says. “It just pops out unintentionally. It’s something you can put aside, but it’s still always there.”

Not long ago, Landauer scrolled past a photo of Céline, and for a second, she wasn’t sure what she was looking at. “I thought, Oh my gosh, I don’t even know if that’s me or her,” she says. “I don’t know who that is. I don’t know who I am anymore.” She posted it to Instagram with a poll asking “Who is this?” The result: 54 percent Céline, 46 percent Laura.

Landauer has seen Céline live just once, back in 2008 at a concert in Montreal. She tells me that it was great, and Céline was amazing. But honestly? It kind of freaked her out. She was sitting in one of the first few rows, and Céline was right there, almost close enough to touch, wearing a short pink dress that she, Laura, has a replica of, doing all the same moves—kicking and shimmying and pointing—that she, Laura, also does, and it was just… “it was kind of weird?” she says, like she’s not sure if that’s okay. She tries “odd,” and then “strange,” but at some point, words fail and she makes a noise—something like “eeungh.” I took it as that hint of disgust that comes from being too familiar.

I had always imagined you’d have to be somewhat of a Céline fan to be a good Céline impersonator. I had no idea. Fandom is observational, appreciation cultivated with the luxury of distance. Impersonation is more like running a simulation of another human being through the instrument of your body. It’s intimate and self-abnegating and so one sided it hurts me to think about. It’s crushing on someone, vibing them, breathing them in—so close and yet and yet and yet. Meeting all these Célines, I’ve come to realize that imitation isn’t flattery; it’s a whole other language for love.

At one point while we’re talking, Steven Wayne gets a little sad. “You know, I’ve been here twenty years, and she’s never, ever come to see me. Never. And it was just across the street!” he says. He doesn’t just sound disappointed, he sounds rejected.

If you think you have imposter syndrome in your career, just imagine making a career out of being an imposter. Gigs can be sparse, and a solid performer might make $800 for a good night’s work. And, though tribute artists gush about the star they’ve applied their talent to mimicking, they have to live with the possibility that their idol would prefer they just not—not reflect their brightness, not ape their talent, not play them for yuks and cash. They might not see themselves in the imitation at all.

“If Céline does know about me, would she embrace me? Or is she not happy about the idea? I don’t know if I even really want to know,” Brigitte Valdez says. She sent Céline a letter once, years ago, but she never heard back. “Maybe it’s better to keep a healthy distance,” she says, but she sounds like she’s talking herself into it. Valdez admits a bit shyly that she’s written songs with Céline in mind to perform them. She hasn’t submitted anything yet, but she’s getting closer. Maybe she’ll do it soon.

I wanted to find Céline through five of her impersonators—for the luck, for the pattern. Connect the dots and it’s there: five points to make a star. But one Céline flaked on me (she’s gigging on cruise ships, doing Céline on the high seas), and I wound up with only four. I thought it would be all wrong. But, of course, it’s obvious: Céline is the fifth Céline. Two plus two plus the gondolier makes five, and Céline Dion is here for it.

There is a video of her that went viral in January 2018. A seemingly drunk woman makes her way onstage during a concert, swings a leg around the singer’s willowy frame, and gives her a solid, canine humping. Céline’s reaction is to sing the Barney & Friends theme song: “I love you / You love me.”

As security moves in, Céline keeps the woman close: “Look at me in the eyes. Do you see my heart?” she asks like an especially earnest hypnotist. “We got something in common. We got babies that we love, and we gonna fight for them. And we’re wearing gold. That’s a sign,” she tells her public molester. As the woman is gently led away, Céline looks out to her audience. “I don’t know her. I love her,” she confesses with a helpless shrug.

It’s moments like this that define Céline. Yes, she is a self-important, all-consuming, unabashedly rich megastar, but she’s one who still insists on recognizing herself in other people. Not every celebrity can do that: convert egotism into sympathy. Céline is sincerely superficial but never superficially sincere. In her world, even the most minor points of intersection have meaning. All those fragmentary details where human lives seem to mirror one another aren’t mere coincidence—they are a pattern, an opportunity, an ethic.

One morning, before the sun is all the way up, Steven Wayne sends me a text: “I met Céline Dion last night.” There’s a picture of the two of them pressed together as if conjoined: Steven-Céline in a black, sequined gown embellished with silver stars, Céline-Céline in a bedazzled cap and pants like a denim cocoon. The shot was taken on the set of a promo video for the Courage tour. Wayne was hired as a Céline doppelgänger who happens to drive up with a car of drag divas when Céline is stranded on the side of a desert highway.

I ask what she was like up close, in real life. Wayne reports that she swore like a sailor and sang like the heroine of a musical and was incredibly gracious. Céline thanked Wayne for impersonating her. He could hardly believe it. Then she repeated it, thanking him again.

The supersized buildings on Las Vegas Boulevard make everything seem close when, really, nothing is. For the three days I spent waiting to see Céline in concert, I paced up and down and up again, passing in and out of microclimates of Juul while being assaulted by light and noise that didn’t so much seem to be competing for my attention as engaging in a badly run conspiracy to murder it. Nothing was really separate—it all came back to the same place, like recursion and corporate cannibalism.

I wasn’t tired; I felt like I was already sleeping or hypnotized. I dosed myself with $4.33 (US) espresso shots that tasted like burned ruins. No matter how hard I tried to stick to the sidewalk, I kept winding up indoors, carpet patterns shifting underfoot. I swear at one point I walked through a wall like a ghost.

I met one Céline and then another. I texted a third from the official Céline Dion boutique in Caesars Palace to show her a marked-down-to-$80 sequined tank top of Céline’s face (I thought it looked more like her). An employee told me the rotation of Céline songs piped through the speakers plays three-and-a-quarter times per shift. He can feel the soundtrack passing through his body every workday.

I tried to get away from the strip and wound up standing on the side of a highway crusted with evidence of life: nests of tumbleweed and garbage and what I’m pretty sure was human feces cracked and half-petrified by the sun.

I went to see the impersonators at Legends in Concert, and they were all very talented singers, yes, I can say that’s true. Céline wasn’t there, but Lady Gaga was, and she brought up the unfortunate coincidence of that other “Lady,” said with scare quotes, who’d taken up residence across the street. But this ticket was a little less expensive, our Lady joked, and the crowd laughed because we were so smart! Two-thirds the Gaga for one-tenth the price! And then she sang “Shallow” with a backup singer who did Bradley Cooper’s part like it was his time to shine in show choir, and please believe me when I say I tried not to find all this tragic and also believe me when I say I failed.

I lay on the floor of my hotel room and listened to recordings of birdsong. I did yoga, bending way back, trying to unzip my sternum and open my critical heart. I watched The Voice and wanted to cry because bodies are temporary instruments and it hurts to see people want things, because the dream is so big and so hard to share.

Finally, I went to see Céline Dion in Céline. It was the fifth day of the month. She would make a rumoured $500,000 (US) for this one show. I walked through the gates of the Palace, and soon she was real: there on the stage that could lift her to the heavens, in the theatre they built just for her, apparating like a blur of glittering pixels, approximately ten feet tall, hair and skin and clothes all spun from some rarified gold. She said thank you to the audience a hundred times. I couldn’t stop laughing—she just reminded me so much of herself. She asked how we were all doing, and I know that’s what they all ask, but it seemed like she really meant it, and 4,000 of us screamed together as if by her grace, in our worship, we’d become one thing. “We got something in common already,” she said, like this was only the beginning of what we would find if we looked, “because we’re doing pretty good too.”

And then Céline sang. It wasn’t like anything I’ve ever heard.

Sarah Palmer is a photographer who has contributed to Toronto Life, Maclean’s, and the Globe and Mail.