At last year’s Paris Fashion Weeks, amid the fuchsia Valentino gowns and fur-trimmed Saint Laurent blazers, an unexpected trend appeared. Model Emily Ratajkowski turned up at the Loewe Spring 2023 show dressed in slouchy two-toned blue jeans and an oversized denim button-down, more affectionately known as a Canadian tuxedo. To the unenlightened, her outfit seemed more Northern Ontario cottagecore than stylish. But InStyle described it as “super-sexy” and “high fashion.” It was one of several denim-on-denim looks to appear both on and off the runway: Bella and Gigi Hadid both wore two-piece denim outfits, while Alexandre Vauthier’s, Balenciaga’s, and Alaïa’s collections all included paired jean couture.

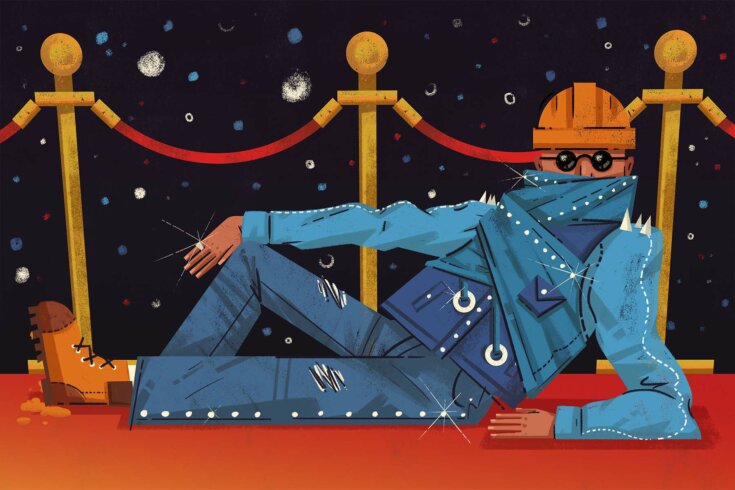

For years, the Canadian tuxedo felt like the butt of a joke, reminiscent of dad rock devotees and sale racks at Mark’s. Now it’s suddenly . . . fashionable? A lengthy list of celebrities—including Rihanna, Dakota Johnson, Kendall Jenner, and Julia Fox—have since donned some version of the Canadian tuxedo in ad campaigns and on red carpets, while Women’s Wear Daily noted spring 2023’s trend as “denim domination.” Fashion publications like Vogue, Glamour UK, and Hello! Fashion have also posted tips for styling denim on denim. So why, exactly, is the pairing—long associated with Canadian non-style—suddenly having a moment?

Despite its name, the Canadian tuxedo was actually inspired and invented by Americans. In 1951, “King of Croon” Bing Crosby tried to check into an upscale Vancouver hotel while wearing his favourite pair of Levi’s and a matching denim shirt. Unimpressed with the casualness of his attire compared to the formalness of other suit-clad guests, a naive desk clerk turned him away. When Levi Strauss & Co. heard about the incident, they designed a bespoke jean tux for Crosby, dubbing it the Canadian tuxedo after the country that prompted its creation (and, perhaps, as a way to take a jab at Vancouver). In a blog post, Levi’s later described the look as an “ironic and cheeky convergence of super-luxe and ultra-casual that was as much a style statement as it was a social one.”

Over the next seventy years, denim took on an entirely new role in fashion. As far back as the early twentieth century, its durability made it the preferred uniform among working men: mainly cowboys, lumberjacks, miners, and railroad workers (all jobs not unfamiliar to Canadians—both practically and stereotypically speaking—which might help explain why we kept naming rights on the Canadian tux long after Crosby debuted his). It wasn’t until the 1950s that denim trousers were more commonly worn as leisurewear, popularized, in part, by the likes of Marilyn Monroe and James Dean.

Even though its popularity was growing, denim continued to be subversive. Jeans of all sorts quickly became intertwined with justice. In 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. wore a work shirt and blue jeans when he was arrested in Birmingham, Alabama—a symbol of the class divide that inspired thousands of other Black activists to don jeans and overalls during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in the US capital. Similarly, denim was the uniform of choice in gender-equality and anti-war protests throughout the ’60s, worn in defiance of the more conservative clothing and ideologies of previous generations (and, in the event of a violent turn, it would also hold up better than something like linen). It wasn’t until the mid-’70s that designer brands like Calvin Klein and Gloria Vanderbilt adopted denim for luxury fashion, making it, for the first time, a staple of high-end style.

In the years since, denim has become a sort of chameleon of fashion: something that can be dressed up or dressed down, fitted or baggy, girly or punk. “Denim has a whole bunch of different meanings based on who you are and when you were born,” says Jonathan Walford, the curatorial director of the Fashion History Museum in Cambridge, Ontario. “What we’re seeing now seems to draw from the whole library of the history of denim. . . . It’s really denim core.” Instead of one specific style or fit being in trend, Walford adds, it’s the fabric itself that’s having a moment.

When I ask Walford whether the Canadian tuxedo is cool again, he seems skeptical. “Maybe ironically cool,” he says.

His speculation falls in line with what Dazed magazine has called the recent “rise of post-internet fashion”—that is, clothing that is sarcastic in nature, shouldn’t be taken too seriously, and is steeped in nostalgia. Perhaps double denim lives here too: a trend that calls back to a different time and is purposely passé—capable of mimicking a catalogue of icons, from Britney Spears and Justin Timberlake’s questionable 2001 American Music Awards outfit to Tupac’s baggy ’90s uniform—yet practical. In many ways, it isn’t so different from the original Canadian tuxedo worn by Crosby—still as much a style statement as it is a social one. Denim has done the unthinkable by blurring the lines of social class, status, and even gender. What was once the most obvious indicator of the working class—blue collar vs. white collar—is now something most people have in their closets. And while most desk-bound employees no longer have the need for workwear, according to Lifestyle Asia, workwear still scratches the itch for a durable, functional garment that works for all body types.

As for its Canadianness, Walford suspects that stereotype isn’t going anywhere. “I think it might be a little bit of a self-fulfilling prophecy,” he says. “We sort of feel like it’s our duty to own it.”