It would be hard to overstate Ferdinand Eckhardt’s impact on the Canadian art world. Eckhardt arrived in Canada from Vienna in 1953, and under his directorship, the Winnipeg Art Gallery became a late-modernist powerhouse. It is not only home to major holdings of international and Canadian works but boasts one of the largest Inuit art collections in the world. For his pioneering curatorial work, Eckhardt was inducted into the Order of Canada, received honorary degrees, and was awarded a Queen Elizabeth II Silver Jubilee Medal. Meanwhile, his wife, Sophie-Carmen Eckhardt-Gramatté, became one of Canada’s leading composers, helping make Winnipeg more receptive to advanced musical ideas from Europe. Both were formative figures on the prairies.

Much of that glamour has now been dispelled following Conrad Sweatman’s revelations of Eckhardt as a Nazi sympathizer—revelations The Walrus published for the first time on November 9. Building on German historian Andreas Zeising’s investigation into Eckhardt’s Nazi writings, Sweatman’s story draws on months of extensive research and is supplemented by scores of documents from archives in Canada, Austria, and Germany. It paints a picture of a man who, after promoting Nazi tenets in his early thirties, moved to Canada and ascended to one of the highest echelons of the country’s art scene.

These findings—since picked up by the Winnipeg Free Press and CityNews—have put pressure on the Winnipeg Art Gallery to confront the truth about its pioneering leader. The University of Manitoba, a beneficiary of the Eckhardt-Gramatté Foundation, announced on November 29 that it is conducting an investigation into Eckhardt’s past and is considering renaming its music library, currently named after Eckhardt’s wife.

I decided to catch up with Sweatman to learn more about the fallout from the article and where he thinks things should go next.

It’s been nearly a month since we published your exposé on Ferdinand Eckhardt’s public endorsements of Nazism. What has the reaction been from the artistic community?

Among younger artists and curators as well as the history professors in Winnipeg who have spoken to me, there’s a sort of shocked fascination and frustration. The Manitoban reported that the sign displaying the name of the Eckhardt-Gramatté music library has since been covered. Things are a little different with Eckhardt’s old allies. I was hoping that, in their stages of grief, they’d move more quickly from denial to acceptance. After all, anyone in Winnipeg can head over to the Archives of Manitoba at this point and get an eyeful of some of Eckhardt’s far-right and Nazi activities during the 1932/33 period.

You’re referring to his memoirs.

That and even more so to a folder called “Kunstkampf,” which includes an additional account of that period by Eckhardt that he titles “Mein Kunstkampf.” In this newly public manuscript—by joining the words “Kunst” (art) and “Kampf” (struggle), the title seems to play on Hitler’s Mein Kampf manifesto—Eckhardt provides some context and rationales for his behaviour, often relating to his precarious financial situation. The folder also includes several relevant letters and articles that show his Nazi involvements run deeper than what he’s prepared to explicitly talk about in his memoirs. And even these documents don’t nearly cover the extent of his involvements. To begin to get a fuller picture, anyone can also access Andreas Zeising’s 2018 profile, in his book Radiokunstgeschichte, of Eckhardt’s far-right writings on arts education, radio, and museums. These materials together show the energy Eckhardt spent in the cultural world egging on the Gleichschaltung, the Nazis’ process of establishing totalitarian control over most areas of German life, beginning almost overnight. Whatever fond memories people have of Eckhardt, this warm sense of him has to make room for unseemly truths. Eckhardt’s foray into Nazi politics is a fact.

In the Winnipeg Free Press write-up about your piece, Stephen Borys, director and chief executive officer of WAG-Qaumajuq, appeared to minimize your findings. Did that frustrate you?

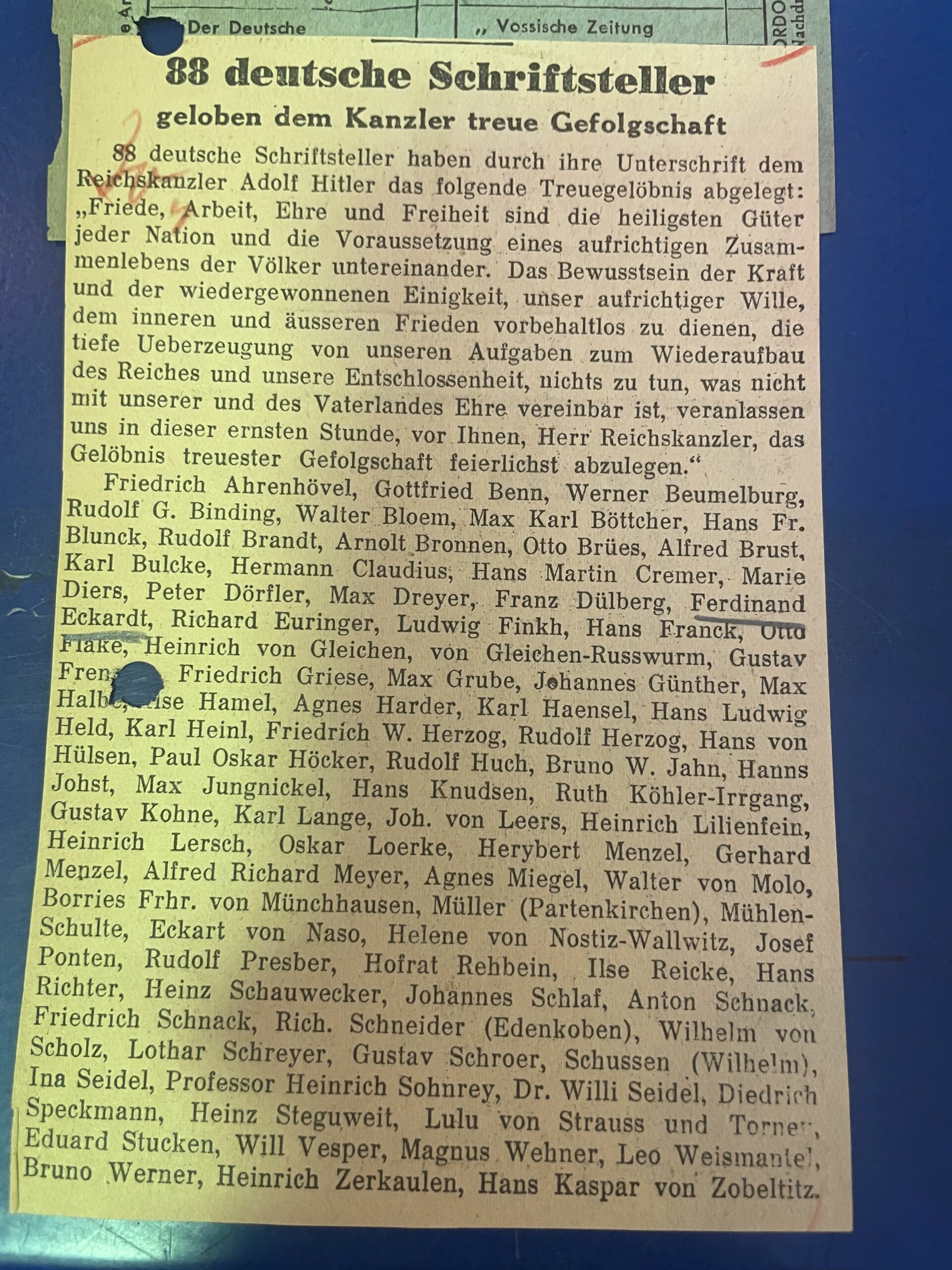

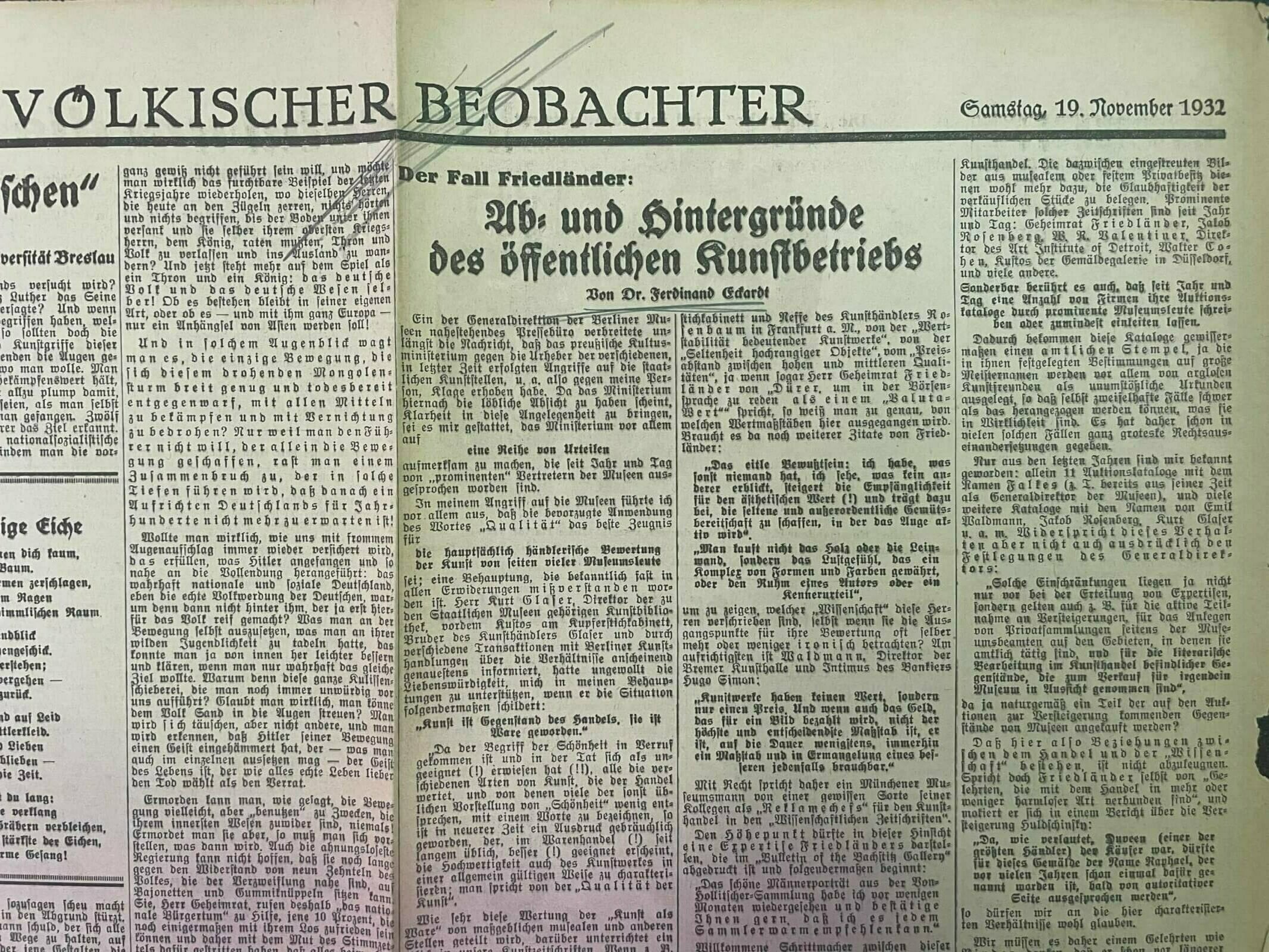

The WAG minimized but didn’t fully deny matters. In a roundabout way, they acknowledge Eckhardt’s involvement in Nazi journalism. They describe Eckhardt as “writing that one article, which he couldn’t get published anywhere else.” The WAG seems to be referring to a 1932 article that Eckhardt tells us he submitted to the daily newspaper the Volkischer Beobachter, one of the Nazis’ main mouthpieces for bile against the Jews. And as we now know, in the year or so following that article, Eckhardt kept churning out pro-Nazi articles. He became lead art critic for the Reich Chamber of Culture, a key institution for the Nazification of German culture, and, upon their encouragement, signed a pledge of loyalty to Hitler. He did dirty work for the KfdK, or the Militant League for German Culture, a group infamous for using violent methods to purge German culture of Jewish influences. Even if we ignore all the other articles and letters available elsewhere and just focus on new relevant folders at the Archives of Manitoba, it becomes quickly clear that Eckhardt was, at least for a period, a vocal, committed Nazi supporter. The WAG’s comments came a few hours after the article’s publication, and they were reeling. But there’s now been plenty of time for them to review the evidence we’ve so far presented.

What do you think the WAG should do?

I hope the WAG can at least explicitly acknowledge that Eckhardt was involved in Nazi politics. It’s possible a more complex assessment of Eckhardt may ultimately emerge, but first the basic facts.

Do you really think the WAG was entirely clueless about Eckhardt’s Nazi dispositions? You’ve reminded me, more than once, that even a simple Google search brings up elements of his past.

I’m not inclined to be overly cynical about the contemporary WAG. Still, a lot of people—and this goes for folks inside and outside the WAG, stretching back for decades—give Eckhardt the benefit of the doubt on too much. Like the fact he worked in advertising and pharmaceuticals for IG Farben, which Eckhardt never denied. IG Farben, lest we forget, is a company whose leaders were tried for war crimes that included the use of slave labour and the production of the poison gas used to kill millions of Jews at Nazi death camps. Saying, as some do, that Eckhardt was peripheral to the atrocities only takes you so far—as eminent historian Peter Hayes has said, “the killings were an open secret within Farben.” Eckhardt’s Winnipeg allies also don’t properly dig into a lot of information concerning his Nazi past that’s been pretty readily available for years. This sort of homework seems basic when we’re considering someone active in German professional life between 1932 and ’45.

And to what do you attribute that benefit of the doubt?

Eckhardt has this “founding father” aura not just for the modern WAG but also, with his wife, for prairie modernism generally. All of this makes it tough for people. I guess, for a long time, the thinking for many was, “Who are we, as bush league Winnipeggers, to question such cosmopolitan, modernist European fancy-pants as the Eckhardts?” Meanwhile, in reality, Eckhardt had aligned himself with one of the most brutal regimes to ever exist. I can understand people being sloppy with their homework. I even get people being a little indulgent toward an old friend when signs of inconvenient truths emerge. This is all too human. But a loud foray into Nazi politics, once discovered, can’t be treated as a foible.

I think it’s worth discussing some of the damning material you found that, in the interest of space, we decided not to explore in detail in the article.

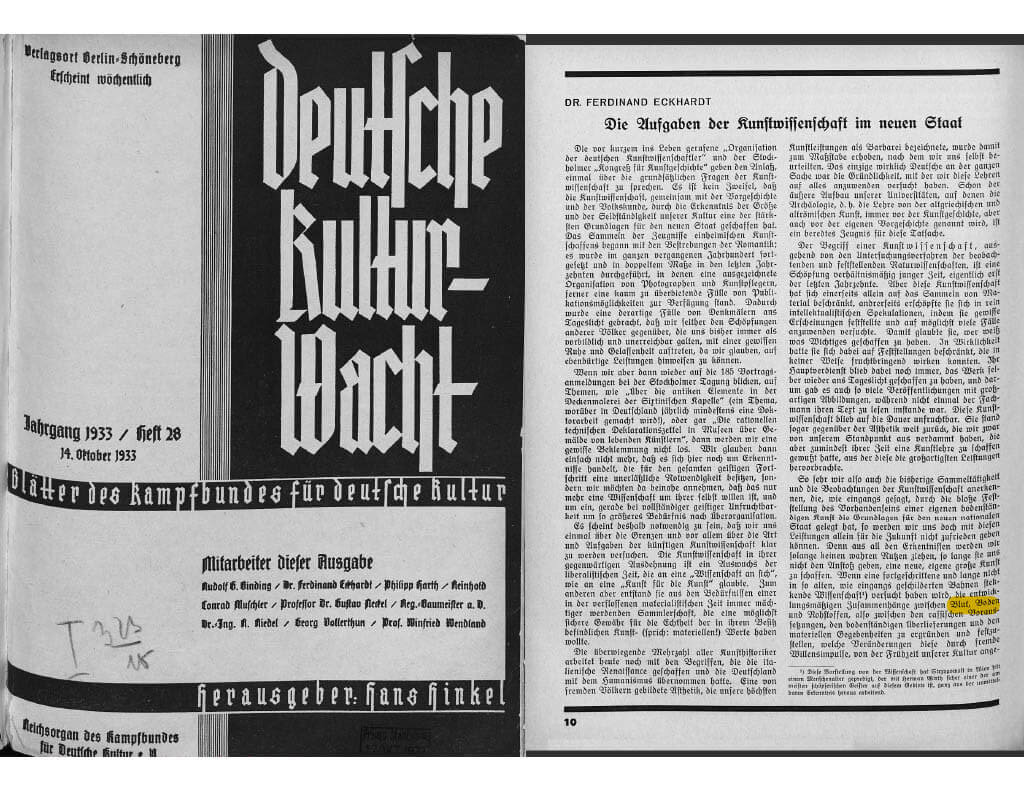

Sure, let’s get into a few things. In Eckhardt’s memoirs at the Archives of Manitoba, he mentions associating with the KfdK, that society of antisemitic goons I referred to earlier. In this connection, he also keeps a letter he sent to the KfdK about his involvement, as their representative, in a 1933 art exhibit. He explains his decision to remove an Otto Pankok painting because its depiction of Christ “with pronounced Jewish features might not completely match the idea of what Germans imagine the Saviour to be.” In the KfdK’s journal Deutsche Kultur-Wacht, an official Nazi outlet, we also find articles by Eckhardt published in 1933. In a similar connection: at the Germanisches National Museum, which houses part of Eckhardt’s estate, we find friendly correspondence to Eckhardt from Paul Schultze-Naumburg about Eckhardt’s writing. Naumburg is a notorious name in Nazi cultural politics and someone likewise linked to the KfdK. Naumburg was known for holding up modernist paintings in lectures beside medical photographs of deformed or diseased people; both, he told his audience, represented the same degeneracy. He was a key influence on the Nazis’ 1937 Degenerate Art show, a takedown of modern art. It’s one of the most odious exhibits of all time. Eckhardt’s KfdK connections are interesting because they point to his alliance with some of Nazism’s most anti-modernist elements. This is ironic given Eckhardt’s reputation in Canada as a father figure in prairie modernism.

And is your sense that there’s still more there to be potentially dug up?

There’s a lot of intriguing threads and loose ends we haven’t discussed, and more keep appearing all the time. For instance, I recently found a 1990 interview attributed to Eckhardt in a book called “Entartete Kunst”: Ausstellungsstrategien im Nazi-Deutschland by Christoph Zuschlag. In this interview, Eckhardt recounts stealing a Walter Gramatté print that had, in turn, been expropriated by the Nazis. While the bold act speaks to Eckhardt’s fondness for the artwork of his wife’s late first husband, one wonders who this piece’s original owners were and whether the piece was ever restored to them. As Zuschlag comments after quoting Eckhardt, “The fact that this was probably not an isolated case should not be disregarded when considering the whereabouts of lost exhibits today.” It’s also interesting to find a 1953 letter—the same year he moved to Canada—that Eckhardt sends the Vienna police. It protests his innocence after his arrest at the Kunsthistorisches Museum on suspicion of art theft, concerning another object. The letter comes from his personnel files at the museum, where he worked after the war. So, yes, it’s hard to say what else will emerge—there’s still many other sources, libraries, and archives to tap and threads to tug.

Why was it important for the Nazis to have its artists on side?

Good question. Despite his mediocrity as a painter, Hitler supposedly still called himself “an artist and not a politician” as late as 1939. Very quickly, this supposed aesthete would show the world the deadly, colossal scale of his political ambition. Nonetheless, his comment reminds us of how important the arts were to Hitler and Nazism. The Nazis conflated modernism with biological and cultural “degeneracy,” which for them certainly included Jewishness. The flip side to all this was the Nazis’ championing of neo-classical art: a lot of kitschy knockoffs of hunky ancient Greek and Roman statues that presented a vivid embodiment of Nazis’ ideals of racial hygiene and biological fitness. Artists conforming to this style could be made officially celebrated artists by the Nazis overnight. So art mattered for the Nazis—it wasn’t just for financial gain that they plundered hundreds of thousands of paintings across Europe. They were also trying to build the world’s most impressive art collection, some of it for eventual display in the unrealized Führermuseum, which would inspire the German Volk towards greater supremacy.

How did Eckhardt’s art writings fit in with what the Third Reich was trying to do?

Taken together, Eckhardt’s writings from the Third Reich’s early years draw a familiar dichotomy between a racial Volk and a liberal, money-grubbing elite whose degenerative influence over the German arts world demands a decisive clean-up by the “new state.” The Reich Chamber of Culture, of which Eckhardt was made lead art critic, was under Joseph Goebbels’s control. Radio was incredibly important to Goebbels, and the Nazis, as a propaganda tool. So it’s no surprise that we find him writing several articles in the radio press about how this new medium might advance the goals of National Socialist arts education. One article even has Eckhardt seemingly auditioning for a role in Goebbels’s propaganda ministry as head of an “experimental centre for art broadcasts” dreamed up by Eckhardt. Eckhardt’s radio-related articles, read beside his museum-related articles, show that he was capable of serving multiple agendas within the Third Reich’s early cultural politics. All while broadly towing the party line.

I find it incredible that the WAG harboured such a figure. But it does seem to fit into a disturbing pattern of Canadian indifference to Nazi expats in the country.

The theme of Nazi expats operating freely in Canada is obviously a popular one right now, especially after the recent Yaroslav Hunka affair (when the Waffen-SS ex-member living in Canada was given a standing ovation in Parliament). I think it’s important to morally distinguish war criminals and SS men from Nazi fellow travellers like Eckhardt. But it’s also important to cut through the horseshit of the “inner emigrant” posture struck by people like Eckhardt feigning a subtle rebellion against Nazism which never really took place. The story of Eckhardt reminds us how readily seemingly ordinary Germans succumbed to the Third Reich’s momentum.

And in the case of Eckhardt, we succumbed in turn, didn’t we?

I think that quality of ordinariness—the fact that someone like Eckhardt looked a lot like “we liberals” with his cosmopolitan sensibilities—helps to explain how certain Nazi types infiltrated our liberal culture and institutions. To come to grips with Eckhardt, I think we also have to understand Canadian liberalism’s sometimes confused culture of tolerance. A tolerance that is also a source of hypocrisy—moral strength distinguishing us from intolerant enemies and naive weakness in the face of their advances. But there’ll be time for a more nuanced conversation surrounding Eckhardt, an accomplished figure also responsible for a considerable pro-Nazi output. Right now, we need the WAG to show their mettle. When an influential public figure traffics in history’s most heinous ideology, it’s in the public interest for us to clear the air. So let’s get it over with.