It’s coming. So says not just Mark Zuckerberg, who recently renamed Facebook in his anticipatory certainty, but a growing chorus across tech, gaming, entertainment, and fashion. Recent headlines proclaim that a slew of megacorporations—Microsoft, Disney, HTC, Dropbox, Samsung, Nvidia, Nike—are getting ready. As the Washington Post reported early last year, Silicon Valley is “obsessed” with what it called “this next frontier.”

Listen to an audio version of this story

For more audio from The Walrus, subscribe to AMI-audio podcasts on iTunes.

And what is this frontier? Matthew Ball, Amazon Studios strategist turned venture capitalist, announced it as a “quasi-successor to the Internet,” with comparable impact and importance, that will give users an individual “presence.” Today, we log on to a disconnected set of disparate experiences: we have various social media accounts where we interact, gaming accounts where we play, and streaming accounts where we relax. There is no continuity; you maintain a distinct identity on each site. The Metaverse will change that. It will provide a sense of place, of geography populated by a singular you and others. No single company will build it; instead, it will be constructed collectively: an interlocking set of interoperating worlds. It will be like an immersive video game you will “live” in—one that never ends, has no one set of rules, and can be joined by anyone at any time. Its activities and economy will span, as Ball writes, “the digital and physical worlds, private and public networks/experiences, and open and closed platforms.” And it will be fully interactive, a dream everyone is dreaming with you.

Roaming the vastness of the Metaverse, you’ll be automatically grouped with friends, or strangers you’re likely to find interesting, and you’ll see their custom avatars around you—the figures that represent their presence, featuring limited-edition virtual clothes, logos, accessories, and badges. Together, you might stumble onto a digitally constructed haunted house or surface in the middle of an intellectual salon or beam into a yelling throng watching a live concert. Perhaps you’ll have a pass that grants you VIP access, virtual swag, or a celebrity companion. At work or school, you’ll collaborate and learn in Metaverse rooms kitted out with whiteboards or screens or productivity tools, sitting beside coworkers all garbed in bespoke pixelated guises. Think of it as a 3D marriage of Zoom, Slack, and Xbox.

The Metaverse is often portrayed as a shared virtual-reality hallucination users experience via headsets that hijack their eyes and ears. VR’s most prominent startup, Oculus, was purchased by Facebook in 2014, and Facebook now sells Oculus Quest headsets, which dominate the VR market. VR also has a more sophisticated cousin, “augmented” or “mixed” reality (AR), in which apparitions are overlaid atop real-world sights and sounds: a fantasy dragon might perch on your coffee table or your walls might turn translucent, revealing the wiring, studs, and ducts hidden within.

Ball, however, is careful to stress that the Metaverse does not require any such headset interface and may play out on simple screens. I suspect this is largely because AR and VR have been one of tech’s great disappointments. As the gaming website Polygon recently put it, “The VR revolution has been 5 minutes away for 8 years.” Its promise and disappointments go even further back. There was a VR moral panic a full thirty years ago, with accusations that it would be “electronic LSD.”

We should have been so lucky. Instead, it remains a fringe activity. In my experience, even the best AR/VR experiences, such as soaring bird’s-eye views of earth’s most beautiful places or intricately detailed science-fictional settings, feel extraordinary for about ten minutes. After the shock of delight wears off, one finds oneself bored, uncomfortable, and all too aware of the tech’s prosaic restrictions: cumbersome headsets, a limited field of view, and for some, motion sickness. The great hope of mixed reality was a headset by a startup called Magic Leap, which promised to seamlessly mix real and fictional worlds without compromise. But, despite spending $2 billion, it was unable to miniaturize its technology.

The struggles of AR and VR shouldn’t really matter to the Metaverse. You can see others’ avatars perfectly well, albeit in 2D, on your smartphone and laptop screens, after all; surely those are sufficient? Maybe. But, if this longed-for Metaverse revolution doesn’t involve new hardware and new forms of interacting with technology, then it’s hard to see how it’s much different from Second Life, a Metaverse-like video game from two decades ago that’s still around, with computer-generated representations, spaces, art exhibits, salons—and barely any users. A very Metaverse-ish startup named Shaker won the TechCrunch Disrupt contest back in 2011 and shuttered five years later.

A Silicon Valley truism holds that being too early is indistinguishable from being wrong, but it’s still fair to ask: Why should anyone take the Metaverse seriously? Every tech startup can tell a story about how wonderful its platform will be once everyone starts using it; investors know that the hard part is getting those users on board. The same is true of the Metaverse. Nobody has yet detailed what exactly will attract people from individual platforms to the nascent Metaverse beyond the tacit assumption that, “if we build it, they will come.” The tech industry has long had a contemptuous term for software products that have been trumpeted but do not yet exist: vapourware. Steve Jobs would never have announced that Apple was becoming a smartphone company without having one already in hand, ready to demo and then ship to customers. The Metaverse is still vapourware, and vapourware always smacks of desperation.

There are three reasons, however, why the Metaverse isn’t hucksterism, which I shall address in order of increasing cynicism:

First, it’s already happening. Fortnite, an online game with over 300 million players and $5 billion (US) a year in revenue, already draws audiences exceeding 10 million to in-game concerts that have nothing to do with gameplay. Many more are growing up on Roblox, a platform for gaming and game creation whose 200 million monthly users include more than half of all American children. Pokémon Go, a game that overlaid its world on our real-world geography, was a worldwide sensation. The recent eruptive success of NFTs—essentially numbered digital art prints with “ownership” registered on blockchains—shows that people will pay real money for digital goods. Facebook planted its first Metaverse seed two years ago: Horizon Worlds (formerly Facebook Horizon), basically a dressed-up version of Roblox for grown-ups. All of the above, and many more, are already grasping toward our Metaverse future from different directions, like vines reaching toward sunlight; it’s only a matter of time before they meet and intertwine.

Second, it’s inevitable. Love or hate Zuckerburg, his acquisitions of Instagram and WhatsApp and his attempt to buy SnapChat, all of which subsequently saw usage skyrocket, show that his crystal ball is much clearer than most. The dominant cultural trend of the last thirty years has been our online lives’ increasing absorption of time, attention, and importance. Every year, we spend more time in abstracted, mediated digital experiences, from Twitter to TikTok, World of Warcraft to Netflix. Studies indicate that the average American now spends four hours per day on mobile devices, up from 2.5 in 2014. A 2019 survey reported that the average Canadian spends eleven hours per day looking at screens. And this overall trend has been greatly accelerated by the pandemic: a remarkable recent study in JAMA Pediatrics indicates that teenagers’ screen time more than doubled during lockdowns, from 3.8 hours per day to 7.7. Through that lens, the Metaverse isn’t a radical change at all; it’s just a rational extrapolation of this inexorable cultural wave.

Lastly, no one in tech can risk not taking it seriously. The industry assumes that we live in a world of endless revolutions: venture capitalists invest in startups, they battle to build what Michael Lewis called “the New New Thing,” the winners become the new venture capitalists and tech execs while the previous generation’s behemoths fight to stay relevant in the new new world, repeat. With AI improving more slowly than expected and self-driving cars therefore on indefinite hold, the Metaverse now seems the most likely New New Thing. As such, a lot of absurdly wealthy venture capitalists and CEOs are about to spend enormous amounts of money to help build it—or to protect themselves from losing users to it.

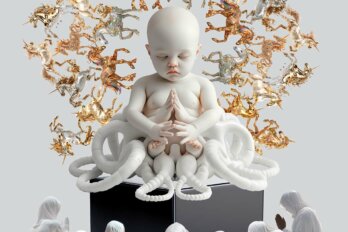

So “Will it happen?” is not really the question. A better question when it comes to tech revolutions is “Should it happen?” The answer there is thornier and more complex. The word metaverse was coined by Neal Stephenson in his 1992 novel, Snow Crash. His metaverse was no utopia. It was a vaguely tolerable, corporate-owned flight from the semidystopian “meatspace” world, where Snow Crash’s protagonist (conveniently self-named “Hiro Protagonist”) lived in a storage unit and eked out a living delivering pizzas for the mafia. The Metaverse’s other literary touchpoint is Ernest Cline’s Ready Player One. Here there is nothing semi about the novel’s dystopia: chapter one begins, “I was jolted awake by the sound of gunfire in one of the neighboring stacks,” wherein a stack consists of dozens of mobile homes arrayed vertically and cities are composed mostly of such stacks.

It is easy to envision, especially for the Roblox generation already spending up to half of their lives on screens, not so much an exodus as an “introdus” away from the physical world and into the Metaverse. This is especially so if, as Stephenson and Cline half-prophesied, political failure and climate change and rapacious inequality combine to make that physical world increasingly undesirable.

Perhaps the grimmest yet most compelling argument for the coming of the Metaverse is that it will offer us all a way to better escape from reality. (We certainly could have used it during the pandemic.) As our meatspace world gets worse, the triumph of the Metaverse grows more assured. Or, put another way, a bet on the Metaverse seems like much less of a long shot in a worsening world.