In July 2013, Sarah Treleaven and her partner, Jamie Levin, started looking for someone who could make some basic repairs to their house in Toronto: the gutters were old and rusty and had to be fixed, and the exterior trim needed to be patched and painted. They thought the project would amount to a few days’ work. When Jamie began soliciting quotes from a few contractors, a friend, Simone, said that she’d had a good experience with a tradesman who had recently done work on her home. The search was over.

Listen to an audio version of this story

For more Walrus audio, subscribe to AMI-audio podcasts on iTunes.

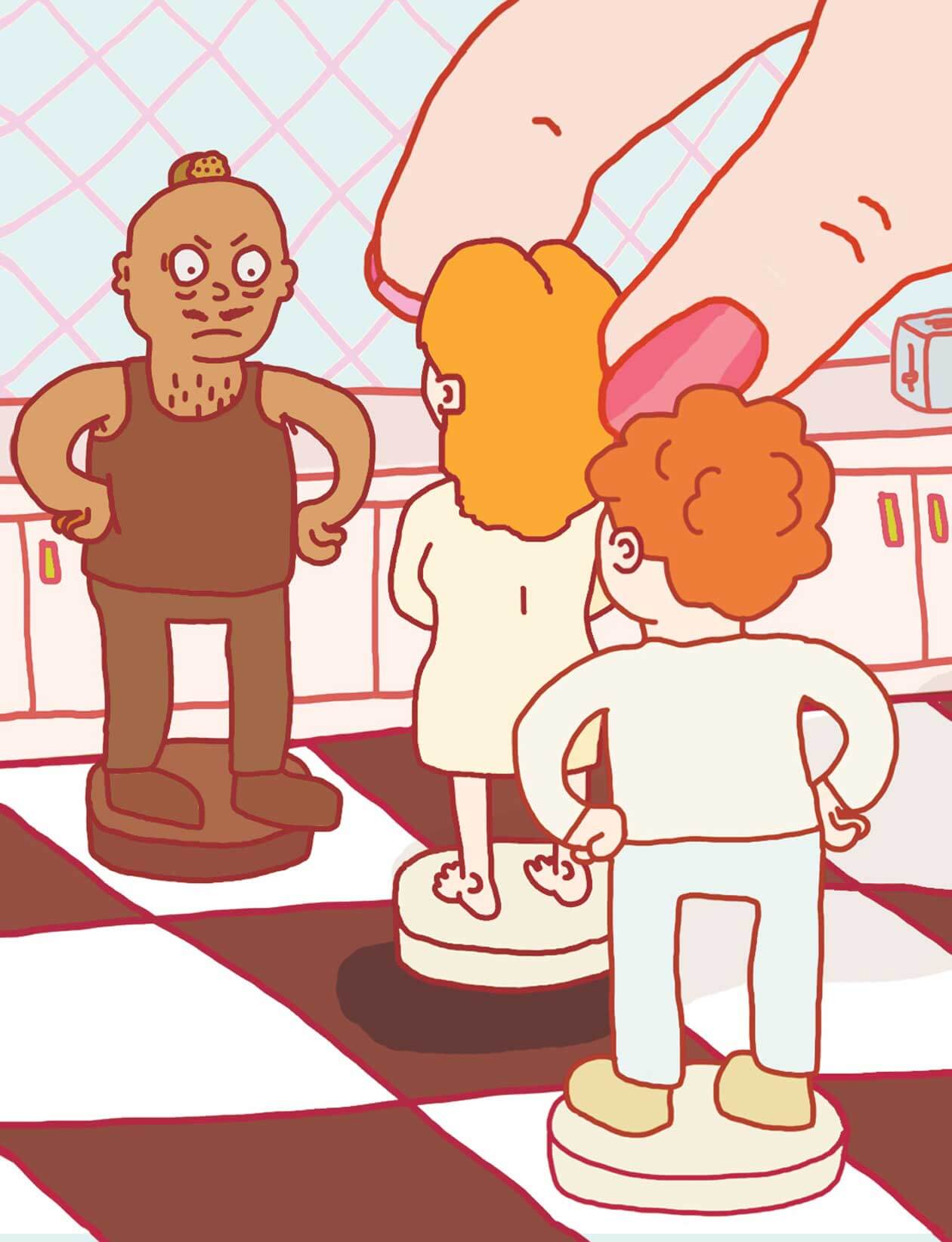

The handyman showed up as promised. He was pleasant and accommodating, and the first day of work went well. Paint was stripped, holes patched, gutters removed.

Jamie: On day two of the repairs, I was rushing out the door on my way to deliver a lecture at the University of Toronto, where I was finishing my PhD in political science. I ran into the handyman outside.

“The job is done,” he said. But it wasn’t. The paint needed a second coat, maybe a third. The repairs stopped midway up the house—nothing had been done above the reach of his short ladder. Worse, a gaping hole, about a few feet long, had materialized in the front of the house after he had pulled off a large piece of the facade, taking bricks with it in the process. Unless it was sealed, rainwater would seep in and all manner of wildlife would find a comfy new home.

“The job isn’t done,” I told him. But the handyman was finished, and he wanted his money. He suddenly towered above me, radiating aggression. He wanted his money now.

Sarah: I was sitting in the living room, avoiding my work as a freelance journalist by browsing the internet, when I heard a commotion outside. As soon as I stepped out onto the porch, I saw that things had gone south with the handyman. I had two responses: annoyance over the scene unfolding in our front yard, and an obnoxiously superior sense that Jamie was likely making things worse by overreacting.

Jamie: I quickly backed away from the handyman and crossed the street, putting distance between us. He turned and went up the ladder, calling at me from above, threatening damage. He started prying at the gutters. I told him to get down, and said that he was trespassing. It wasn’t courage or conviction—it was instinct. “Get down. Take your tools and go.”

But he didn’t. Confrontation is not in my nature. I might spar intellectually with friends and colleagues—Sarah would call me argumentative—but a physical skirmish is completely foreign to me. I called the police. My hands were shaking as I dialed the number. I made a visible show of placing the call, and that motivated the handyman to leave, but not before he issued a warning. You will regret making an enemy of a handyman, he said.

Later, the police came and Sarah and I made a report. The officers were largely indifferent. “Call us if anything happens,” they advised. Still, I was feeling better. I had recovered my composure and Sarah seemed fine. We thought it was over.

Sarah: In the days after this incident, we laughed at the handyman’s parting words—a curse worthy of a flamboyant Disney villain. Our new enemy, the handyman! We went back to our lives. But it turned out the handyman was right: we did end up regretting that we’d made an enemy of him. Given what happened next, we both wish we had just ignored the damage and pressed $1,200 into his hands.

About a week later, Sarah and Jamie heard a knock at the door. Standing on the front porch were two firemen who had received a complaint that an illegal boarding house was being run out of their address. It took a moment for Jamie and Sarah to put two and two together—this was the handyman’s attempt at revenge.

Jamie: Maybe a couple of days after that, there was another knock. This time it was a city bylaw officer, responding to the same complaint. “We don’t operate a boarding house,” I explained. “This is our home.” There was another search, another invasion of our lives. All the same, we decided that these “anonymous” complaints were mostly harmless—the act of someone with a limited imagination.

But we did start to wonder why our close friend Simone had given us the number of such an incompetent and—worse still—vindictive handyman. When we asked, she said that she remembered him being a bit brash, but thought his cheap rates made up for that. (Simone would later discover that the handyman had left her and her husband with a leak that plagued them on rainy days.)

A short while later, we received a citation by mail from the City of Toronto, which demanded that we fix the damaged exterior wall of our house. I had explained my story to various city officials—police and fire and bylaw. Yet I was the one being reprimanded.

I had the wall fixed before the autumn chill set in, and there were no more unexpected visits from city officials.

In mid-October, a registered letter arrived. Sarah was on the phone at the time, and she hastily signed for it. The letter had the University of Toronto, Jamie’s employer, scrawled as the return address. When she got off the phone, Sarah opened the envelope and found part of a television manual—and nothing else.

Sarah: When I pulled out the manual, my stomach dropped. I knew there was something sinister about it—the booklet was open to the section that deals with electrocution warnings. What could this mean? It seemed absurd, but was it some sort of oblique threat? I immediately thought of the handyman.

We called the police. They didn’t seem interested. Next, we called all the lawyers we knew—including my dad and stepmother, as well as Simone and her husband. We were hoping they might have a magic cure, some deterrent or punishment we hadn’t yet thought of. They were all stumped.

Jamie started to think about why someone might want to send a registered letter. If this was the handyman and he just wanted to do something weird, why spend the extra money on a registered service? It was something to do with the signature. And why would you need a signature?

Jamie: When you sue someone in small claims court, you need to submit an affidavit attesting that you have notified the defendant and served them with all the relevant documents. You do so by swearing an oath and providing proof of delivery, such as the return receipt from a registered letter. Simone offered to take me to the courthouse to test my theory. I was proven correct and, for a small fee, was able to get copies of the documents the handyman had filed. All we had received in the mail was a television manual, but the handyman’s sworn affidavit indicated that we had been properly served. He was claiming several thousand dollars in damages against us.

Even though the handyman had used fraudulent means to sue us, the machinery was still in motion. We had a limited amount of time to respond. If we didn’t, a default judgment would be automatically awarded against us. Our next course of action was to file a counterclaim.

For the first time, I began to feel that we might not be dealing with a small-minded thug. The handyman wasn’t just petty; he was calculating and deceptive.

I took the lawsuit seriously and became something like a sleuth crossed with a jailhouse lawyer. I spent countless hours online investigating the handyman. I uncovered numerous other complaints against him for shoddy work. I filed statements of claim and counterclaim (in triplicate). I had documents served. I filed affidavits—each one meant a new visit to the courthouse and the payment of more fees. I even assembled full-colour exhibits and lists of witnesses, and rehearsed my arguments.

Over the winter, spring, and summer, the court case hung over our lives. In the fall, more than a year after the whole ordeal began, we had our day in court. After waiting for the handyman to show (he never did), the judge dismissed his case against us and then proceeded to review our claim. He awarded us $8,650 in damages. But to my surprise, he did nothing about the handyman’s attempted manipulation of the court system.

It didn’t feel like a victory.

Sarah: We had won. That’s what happens at the end of the movie, right? I figured that we would never see any actual money, but we had this judgment to hang over the handyman’s head in case he ever gave us trouble again. I thought we had taught him a lesson about sending television manuals and filing false affidavits. This was an example of the system working, just as we always believed it would.

But then Jamie decided that he actually wanted to try to collect on the judgment. I couldn’t believe it. We finally had leverage over this guy who had proven he had a taste for retribution, and Jamie was going to poke the bear again? All of our friends were opposed. Our parents were opposed. Jamie accused me of being too cautious and WASPy, of wanting to avoid confrontation—which was true, but I was still convinced that engaging further with this man would be a mistake.

I found myself begging Jamie to let this lie, but he was unmoved. There was something about the whole incident that made it impossible for him to just walk away with the upper hand. He needed to play it. This decision left me grappling with the terrible sense that what I wanted and needed—the restoration of normalcy—wasn’t as important to Jamie as proving a point.

Jamie: It is true that Sarah was loudly and vehemently opposed to collecting on the judgment. She was convinced it would simply invite more destructive behaviour. But the court appearance had been a letdown. Yes, we were off the hook for damages, but we had spent hundreds of dollars defending ourselves against spurious charges, and thousands more repairing the damage the handyman had done. Why should we be out of pocket?

With the judgment in hand, I emailed the handyman with an ultimatum: pay me promptly and I’ll settle for half of the damages. Don’t make good, and I’ll use the full force of the court system to seek the entirety of the award against your assets. When I didn’t hear back, I hired a paralegal to begin proceedings to seize the handyman’s assets.

One Friday night, weeks after he had issued the ultimatum, Jamie received an email and then a phone call—both from people looking for “massages.” He asked Sarah if it could possibly be a coincidence. She thought that was unlikely. After some creative Googling, Jamie found the source: the local paper had run a classified ad—complete with Jamie’s first name, phone number, and address—that listed their home as a brothel.

Sarah: We scrambled to get the ad taken down that night. We called the police. Yet again, they were uninterested. One cop actually thought it was a hilarious prank. We called the paper and got its voice mail. Jamie called another brothel, the one from the ad next to ours. They proved tremendously helpful—the proverbial sex workers with hearts of gold—and got the ad removed.

I felt like my basic sense of security had been violated. We now had a nemesis who wanted to make us feel unsafe in our own home. And every time the handyman upped the ante, we were shocked. It was a total failure of imagination on our part. A few times that night, as he was calling the numbers on escort ads, Jamie tried his best to make light of the situation. “Maybe we can pick up some extra cash,” he offered. “Looks like this episode is going to have a happy ending after all.” But I wasn’t in the mood to joke. I couldn’t shake my sense of impending doom. I was furious with Jamie for prolonging this ordeal and for failing to see the possible outcome of his determination to get even. The things we had previously enjoyed together—long weekend walks and marathon cooking sessions and making up stupid songs to sing to the dog—had been replaced by endless conversations about how to strategize our way to a satisfactory conclusion to the handyman situation.

Jamie: The next day, I received an email from an unknown sender. “If you don’t transfer by email $1,000 in timely fashion . . . then you, your family and anyone associated with you in this business will be dealt with.” So it had come to this. We were being extorted. We called the police—again. This finally got their attention. Our case was transferred to a detective. He made promises: an arrest would be made; charges would be laid.

Sarah’s fear was suddenly infectious. I began checking and rechecking the locks. I installed security cameras. I scrutinized street traffic. But at least we finally had the attention of police. Despite my increasing anxiety, I felt that there was light at the end of the tunnel. We just had to keep it together long enough for justice to be done.

The Truth About Mr. Jamie Levin, PhD Candidate.” That’s what the email said. In late October, it was sent to a number of Jamie’s colleagues and superiors at the university. A link led to a crude website claiming that Jamie had embezzled money in a previous job, and a “commenter” claimed that in Jamie’s position as a PhD candidate teaching undergraduates, he was accepting cash for grades.

Jamie: I was nearing completion of my PhD, about to defend my thesis, and I was in the midst of applying for academic jobs. Anyone searching for me online would find the website. The allegations were nonsense—my friends knew it, my mentors and supervisors knew it. But would a hiring committee? My colleagues and friends rallied around me. One major figure in political theory emailed and offered to intervene on my behalf. “Sorry about the evil slandering asshole, I’d be delighted to punch them in the face,” she wrote, channelling Tony Soprano more than Socrates. But I felt helpless.

I tried to get the website taken down. It didn’t work. I checked in with the detective, who advised me to be patient. Time passed and I didn’t hear back, so I began leaving messages for the officer, only to learn that he was out of the office: on vacation, on leave, on extended training.

Sarah: I was travelling for work when Jamie Skyped to tell me that the handyman was now trying to destroy him professionally. I can’t remember where I was—I think I might have been in Lima, coping with food poisoning from some bad chaufa. I was afraid for Jamie, and horrified that someone hated him this much. But I was also afraid of how Jamie would react. His anger and frustration touched a nerve for me, and I was seized by anxiety every time I felt his emotions intensify. The handyman was clearly Jamie’s nemesis. For me, it was a little more complicated. I felt like I could deal with an enemy outside the gates, but the growing rift within our own home was a bigger challenge.

After two mostly very happy years together, we were surprised to learn that we became completely dysfunctional when confronted with a crisis. We fell into a cycle: Jamie would demand that this issue monopolize our attention; I would resist; we would both feel resentful, and then accuse each other of being uncaring. We were forced to ask ourselves how much conflict a relationship could bear. And what is the true mark of a robust relationship—how you deal with each other on a daily basis, or how you deal with each other in a worst-case scenario? There were points during this episode when, after returning home, I would just sit on the front steps because I didn’t want to go inside and start the cycle all over again.

Throughout this whole affair, a part of me strongly wanted to minimize everything that was happening and stay cool and rational. But when I got back from my trip, I had coffee with a friend one afternoon and filled him in on the latest update. I can still remember the horrified, incredulous look on his face when he heard about the handyman’s campaign—an expression I had never before seen in our almost twenty years of friendship. Finally, he put his head in his hands and said my name. I didn’t want things to be that bad. I also started to wonder if I was the one living in a fantasy.

What kind of person would go to such lengths over a perceived slight? At the end of December 2014, Sarah and Jamie went online (again) in an attempt to find out. They soon thought they found an answer: an accused war criminal. There were court documents that referred to someone with the same name as the handyman and contained appalling allegations—he had been accused of torture and the murder of his compatriots. This man had been deported from Canada, and spent time in a jail here for uttering threats. Yet he seemed to have thwarted immigration authorities and found his way back to the country.

Jamie: This discovery wasn’t exactly new. While preparing for small claims court, I had come across articles tying someone with a similar name to crimes against humanity. But we assumed it was another person. It seemed too outlandish to be true. It was only after the extortion message and the email to my faculty that Sarah started connecting the dots and thought the two men to be one and the same.

Sarah: At first, I thought this new development was wildly surreal. How could this situation possibly get any more sinister? I mean, it wasn’t like we were dealing with someone guilty of egregious human rights violations and breaking international laws, right? And then, suddenly, it seemed like we were. My amusement had dipped by the time the sun started to set. By nightfall, when I let the dog into the backyard, I lingered in the doorframe to keep an eye on him. I thought about how easy it would be to poison our tiny, not terribly bright dog. Soon, my imagination was running wild. The handyman wasn’t just a jerk anymore; he was potentially someone capable of the most horrific behaviour. I was terrified of what he might do next. Every time a car parked in front of the house or a man lingered on our street, I was compelled to check if it was him. I started to worry about Jamie walking home alone at night. What would someone like this do if he really wanted his money, or wanted to avoid paying a debt? I pictured a baseball bat and a fractured skull.

Jamie: I count myself firmly in the liberal internationalist camp. As a Jew whose extended family perished in the Holocaust, I am keenly aware of Canada’s dark history just before the end of World War Two, when many refugees and immigrants weren’t welcome. Canada’s post-war record of peacekeeping abroad and resettling refugees at home is for me emblematic of how countries—particularly middle powers—can help remediate the worst aspects of armed conflict.

But now, for the first time, I began questioning these beliefs. If the handyman was actually this accused war criminal, how had been let in to the country? And how was it that he’d been allowed back in after being deported? The experience began to affect my moral compass.

Sarah: I started putting hypothetical questions to friends who worked in government. I emailed an acquaintance who worked for Citizenship and Immigration to just casually inquire about how one might go about obtaining some immigration files or alerting someone to a dangerous asylum seeker. I got a well-deserved scolding about privacy rights. At one point, I found myself Googling “how to get someone deported.” All of these acts were half-hearted and felt completely divorced from who I am. I didn’t want to believe that my values were simply a matter of privileged convenience. But I also felt like we were out of options.

Jamie continued to leave messages for the detective. In January 2015, after months of waiting, the couple finally dragged Sarah’s parents—both lawyers—into the police station to meet with the officer, certain that he would take them more seriously. But the detective declared that it was too difficult to trace websites and that there wasn’t enough evidence that the handyman was the responsible party. (At one point, he seemed confused about what an IP address was, pronouncing “IP” as if it rhymed with “yip.”) He promised to keep investigating and to follow up, but Jamie and Sarah were not optimistic.

Jamie: We left the police station dispirited. The damage the handyman had done to the house had long since been repaired, but I feared that the longer the website defaming me remained live, the more damage it would do to my reputation and career prospects.

On top of that, my faith in institutions had been badly shaken. I had long harboured a naive expectation that we could depend on the police for help. When it was clear that this was wrong, I became consumed with anger—at them, at the handyman, of course, and also at our friends and family, who were seemingly unable to help. But mostly at Sarah, who was often dismissive and minimized my feelings or attempted to pacify me. Feeling helpless and abandoned, I socialized less with friends and retreated emotionally from those closest to me. But the bunker of self-isolation did little to mute the fear and the constant sense of dread. Really, it made things worse.

Sarah: In the midst of all of this, Jamie and I went on vacation with his parents to Hong Kong. I was hopeful that this was the break we needed, that the physical distance from Toronto might reduce anxiety and restore some of our connection. It didn’t. One night in the metro on the way to meet Jamie’s parents for dinner, we were suddenly screaming at each other. I walked faster and faster on a moving sidewalk, as though I were making some kind of attempt at escape. My frustration had hit its peak. Is this the moment when people break up? I wondered. But I couldn’t bear the thought of leaving Jamie alone to deal with this.

Jamie: A month later, I was on the phone with my parents. They offered to write a cheque, to pay off the handyman. They couldn’t understand why I wouldn’t walk away. I explained again that it was a matter of values; it was no longer about money or ego. Does one stand up for what is right, even under duress, or do they sacrifice their principles at the first sign of adversity?

After we’d talked for hours, my dad told me he understood my position. It was the first conversation I’d had in months in which someone hadn’t tried to placate me or play down my feelings. That small recognition allowed me to lower my defences and listen—actually listen—to someone else. If I wanted to continue fighting the handyman, my father said, I had a duty to minimize the costs to Sarah. It was then that I realized I couldn’t keep fighting the handyman without inflicting collateral damage. After months of digging in, I finally saw the harm I was doing to her and decided to call a truce with the handyman.

After much deliberation, Jamie emailed the handyman and asked him to take down the website and cease all contact, promising that in return, he wouldn’t collect on the judgment. The handyman wrote back almost immediately and agreed—with a cheerfulness that was irritating. He did, however, insist on one further condition: that Jamie remove the negative feedback he’d posted online characterizing the handyman as a hack and a threat.

Jamie: It was an ethical compromise, not warning other people about the handyman. I felt like we were selfishly setting others up for disaster in return for some much-needed peace in our lives. But I did it because we were desperate for all of this to be over. I wanted justice, but everything I had done up to this point had only made things worse.

Sarah: Jamie was clearly disturbed by the idea of capitulating, and I realized that we had duelling loyalties. Jamie felt obligated to society in general; the thought that someone might go through the exact same experience we had—and all because no one had bothered to warn them—was chilling. I understood where he was coming from. But after more than a year of fear and exhaustion and near-constant fighting, I felt fiercely protective of our little family. Society be damned: we needed our lives back.

Jamie: The handyman lived up to his end of the bargain: the website was removed in February 2015, and the harassment stopped.

Life gradually returned to normal. I stopped looking over my shoulder and wincing every time there was a knock at the door. Sarah and I remain somewhat wounded, and we’re perhaps emotionally weaker than we were when the situation began, but we have grown closer again. Sometimes we even laugh at the ordeal.

I finished my PhD, and we moved to Jerusalem, where I began a research appointment at a university. Still, there’s a lingering sense of loss: I feel as though I compromised too much, sold out my values. We were left with a simmering knowledge of what it’s like to feel truly helpless, and of how shockingly ill-equipped we are to cope with a crisis.

We never did hear back from the detective.

Sarah: I still flinch at the word “handyman.”