On July 4, 2016, ten years into a life sentence for murder, Terry Baker was found unresponsive in a segregation cell at the Grand Valley Institute for Women, in Kitchener, Ontario. The Canadian Association of Elizabeth Fry Societies, an organization that works with imprisoned women, reported that she had a ligature around her neck; her body was scarred from years of self-harm. Baker was haunted by her role in the vicious killing of Robbie McLennan in Orangeville, Ontario, which occurred in 2002, when both she and the victim were just sixteen years old. McLennan was beaten to death in an act of revenge—he had taunted and teased another teenager for not being able to hold his alcohol. Baker pleaded guilty to first-degree murder and was sentenced as an adult, receiving life imprisonment.

Like so many other female inmates in Canada, Baker struggled with mental illness. She engaged in self-harming behaviour throughout her time in custody. At one point, it became severe enough that she was transferred to the Regional Psychiatric Centre in Saskatoon. When she returned to prison, she was in and out of segregation, where treatment for complex forms of mental illness is virtually non-existent. Now Baker is the latest in a growing list of mentally ill women who have died in federal penitentiaries. Canada no longer executes convicts. But for those suffering from mental illness, a prison sentence too often becomes a death sentence.

In 2011, the correctional investigator of Canada reported that about one in ten men and two in ten women entering federal custody had a mental illness. Eighty-six percent of women in prison have also been victims of physical abuse. Some are seriously ill, yet have still been deemed criminally responsible for their behaviour. These people, who are “sane” enough to find themselves in a prison rather than a psychiatric hospital but are too unwell to live safely among the general prison population, are most likely to experience the horrors of segregation—Canada’s very own Catch-22.

When mentally ill prisoners act in unpredictable ways or become difficult to manage, they may be put into “administrative segregation.” There, they are confined to a cell alone for twenty-three hours a day, sometimes in physical restraints—strapped to a bed or a chair, or in cuffs that inhibit their movement. These steps are supposedly taken to protect them, the other inmates, and staff. But in some cases, prison officials simply don’t know what else to do. While Correctional Service Canada (CSC) staff are purportedly trained to address inmates’ mental-health needs, evidence presented at the coroner’s inquest into the death of Ashley Smith revealed that many in the organization, including those specifically tasked with managing complex mental-health issues, have shockingly little knowledge about mental illness and the best practices for working with people who suffer from it.

If psychiatric symptoms are detected and addressed properly, there is rarely any need to use segregation, which can exacerbate mental illness and destabilize people further. Although the CSC has the legislative power to transfer mentally ill people out of prison and into mental-health facilities, it rarely uses its authority in this way. At the same time, there are very long waiting lists for beds in forensic mental-health facilities across Canada, and hospitals are not enthusiastic about accepting transfers from correctional institutions. Forensic hospitals, moreover, are not always equipped to create a therapeutic, supportive environment for patients who have challenging mental-health needs. When inmates transferred there become difficult, it is too easy for the hospital simply to send them back to the prison. Nobody feels truly responsible for providing proper care for offenders with serious mental illnesses.

Very few citizens will ever come face to face with what actually goes on in Canada’s prisons—or with the horrors of solitary confinement. But for those of us who have, it is difficult to understand how segregation is still an accepted practice.

Several years ago, I represented the Elizabeth Fry Society at the coroner’s inquest into the death of Ashley Smith. Ashley died in her cell at the Grand Valley Institute on October 19, 2007, while a prison guard stood by and videotaped her. She was nineteen and had been in segregation for close to four years.

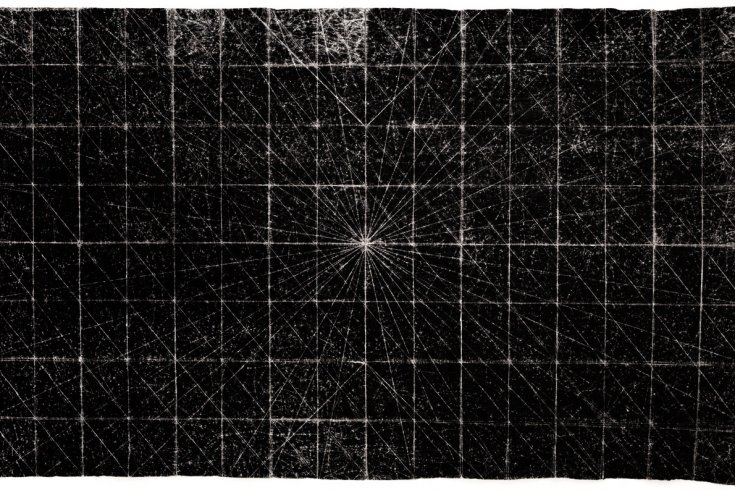

Partway through the inquest, the coroner, jury, and lawyers toured the prison, and we were given the opportunity to go into Ashley’s cell. I asked the officers whether I could go in alone. As the heavy door closed behind me, I imagined how helpless she must have felt in that cement box, which was furnished only with a toilet, a metal slab for a bed, a surveillance camera, and a four-by-twelve-inch food slot in the door through which she communicated with the medical staff and guards.

If Ashley behaved, she may have been allowed out of her cell to shower or to spend a short time in the “yard,” a small cement enclosure. Otherwise, she was in her cell, clothed only in a tear-proof gown, with no blanket or mattress and nothing to occupy her time. She even had to ask the correctional officers for toilet paper, which they rationed out of concern that if they gave her too many squares at one time, she would use them to cover the lens of the camera in her cell and take the opportunity provided to harm herself. (Sadly, such behaviours are not uncommon: prisoners in segregation have been known to make use of any tool at their disposal to help them end their own lives.)

In December 2013, after having listened to the evidence for eleven months, the jury issued a list of recommendations that could have revolutionized the way the mentally ill are treated in the correctional system 1. The CSC was required to submit a report to the coroner detailing the changes it had instituted. But a year later, its response contained more buzzwords than substantive updates. For example, when it came to the issue of mentally ill women being transferred to hospitals to serve their sentence, the CSC boasted that it had introduced a five-year pilot project that involved access to two beds at a psychiatric hospital in Ontario. Yet at the time of the inquest, one prisoner advocacy group estimated there were nearly thirty women in custody that needed psychiatric care.

Terry Baker’s death in the same institution where Ashley died is a painful, unnecessary reminder that prisons can be life-threatening for people with serious mental illness—and that little has been done to mitigate that danger. However, there are signs that political will may be starting to align with common sense: the United States, a country to which Canada typically adopts a condescending attitude when it comes to penal reform, recently banned the use of solitary confinement on juveniles in federal prisons, citing its “devastating, lasting psychological consequences.”

We will never know how Baker’s life would have unfolded if she had received proper psychiatric care in a therapeutic environment. Her legacy now will be yet another coroner’s inquest. But we don’t need another jury to recommend the decarceration of mentally ill people. When Justin Trudeau delivered his mandate letter to the new minister of justice last year, he directed her to implement the recommendations of the Ashley Smith inquiry. It’s now been more than a year since the Liberals took office, though, and little has been done. We should not have to see more suffering and death before they take action.

What We Learned from the Ashley Inquest

In December 2013, the jury in the coroner’s inquest into the death of Ashley Smith made 104 recommendations with a view to preventing deaths in similar circumstances. Many focused on the treatment of women with complex mental-health issues. The jury, for example, recommended:

- that women with serious mental-health issues and/or self-injurious behaviours serve their sentence in treatment facilities, not prison-like environments;

- that women with serious mental-health issues be “promptly transferred” to treatment facilities;

- that there should be an absolute prohibition against holding women in segregation for more than fifteen days;

- that when a woman is held in segregation, she should still have access to programs, activities, and services within the institution;

- that if physical restraints are used on an inmate, one-on-one therapeutic support must be provided while she is in restraints;

- that the CSC make it possible for inmates to have weekly contact with their families; and

- that non-governmental organizations have greater access to CSC institutions and inmates in order to monitor and report on the conditions of detention.

This appeared in the January/February 2017 issue under the headline “Boxed In.”