The first time I heard Tig Notaro talk about her cancer, on an episode of This American Life, I didn’t know about my own. It was the year before I was diagnosed, when my cancer was silently having a field day of rampant cell multiplication in my body.

I’ve been trying to think about how it’s different, reading the same story years later in Notaro’s new book, I’m Just a Person, knowing that I have cancer. Her story is the same, but it lands differently. The litany of misery laced with forthright, self-aware humour is somehow funnier and more intimate. Before, I shook my head, now I nod—a subtle shift that makes all the difference.

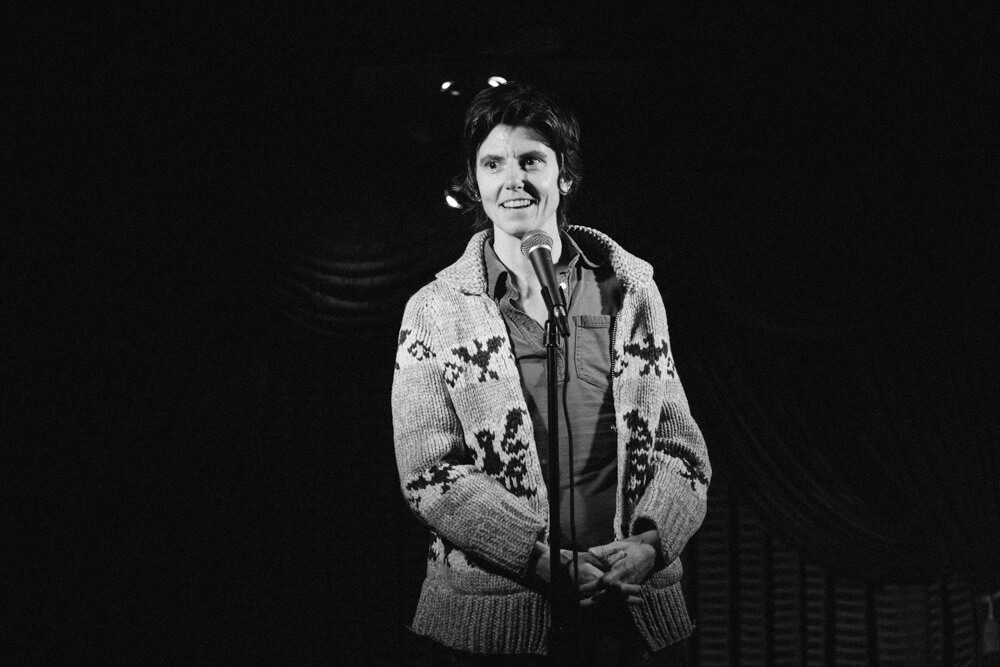

By now, Notaro’s no good, very bad year is public record, so I feel safe recapping its horrors without worrying about spoilers. The day after learning that she had cancer, Notaro took to the stage at Los Angeles’ Largo comedy club and told a packed room, “Hello. Good evening. Hello. I have cancer, how are you?” She then outlined the tragedy-packed four months leading up to her breast cancer diagnosis: pneumonia, a dangerous hospitalization with the intestinal bug C. diff, her mother’s sudden death, and, oh, a breakup. This one evening catapulted Notaro from respected road comedian—a comedian’s comedian, as it were—to the centre of public discourse about cancer.

And fame. It made her really famous.

In fact, the comedy album of that set, Live (pronounced the other way, as in, “and Let Die”), peaked at number one on Billboard’s Top Comedy Albums chart and was nominated for a Grammy. Netflix produced a documentary, Tig, about the show and what came next. The film chronicles a year of searching, looking forward, falling in love, trying to have a baby and finding her way. It’s a charming, if somewhat flawed, documentary. Directed by friends of Notaro’s, the film’s bias is clear. Enjoyable as it is, it feels like it barely skims the surface of its complex subject matter, which includes the extremes of life and death, disease, IVF, surrogacy, and love.

Which brings us to I’m Just a Person, and the question of what is gained through repeated re-examination.

When Notaro walked on that stage at Largo and opened her mouth, she wasn’t sure exactly what she was going to say. What came out was brilliant improvised comedy that captured the intersection of some most human forces: struggle, suffering, love, and compassion. But it’s different telling her story in a book. There’s time, not just timing. The interface with the reader is both remote and intimate. A book affords the room to expand, to reflect, and to correct the public record.

Even though she is an entertainer, Notaro was private about her personal life until one day she opened up and shared deeply. On stage. Perhaps cancer was one misery too many and she broke. When she opened up her personal life, turned it inside out and spilled it across the stage, something changed in her. “Everyone, including me, was living moment to moment, processing raw truths in the dark,” she writes, “I still had cancer, but I felt empowered, as though I had an edge over the competition.” One might say that she stopped being just a person when that set went viral. I would disagree. At the base of tragedy there’s pure humanity. This is where we connect most easily, where one person relates to the experiences of another.

Any one of Notaro’s tragedies would have been enough to disrupt her life. The misery could have broken a person with a lesser sense of humour. Yet it galvanized her. This is where the book gives us more. Notaro frames that awful year with joyful living. It begins with the family that raised her: a wildly charming (or charmingly wild) mother, an older brother, a stepfather who steps up his support after her mother dies, and a largely absentee father. The book closes with the family she chose to love from her tight-knit comedy community.

Like Notaro’s stand-up, the book is breezy, even chatty. It draws you in and warms you up. And flatly, without affect, she tells it like it is. Hers is a quintessentially American story: born in the South, went west for the bright lights of LA, survived tremendous adversity and rapid-fire near-death experiences, and emerged victoriously happy and unstoppably hopeful.

It’s not despite the miseries that the book is uplifting, but because of them. And because of Notaro’s ability to keep getting up, no matter how many times she’s knocked down. She jokes about the inadequacy of the aphorism, “God never gives you more than you can handle!” to provide comfort, ”But I can assure you that C-diff, the death of my mother, and breast cancer were each, individually, more than I could handle. For all of them to be happening at the same time—peppered with a breakup—put me way beyond my limit. I mean, it really felt like enough when I had pneumonia.” She improvised her way through adversity—like the consummate comedian that she is—and landed in a better place than where she began.

Yes, Tig Notaro is just a person who got cancer, like far too many of us. But what makes her special is the way her diagnosis propelled her out of her comfort zone to seize not just life but also living.