The intersection of Queen Street West and Ossington Avenue in Toronto’s west end is the city’s acme of gentrification. Like other evolving neighbourhoods (Montreal’s Mile End, say, or Brooklyn’s Williamsburg), the street fronts display art galleries and clothing boutiques, yoga studios and furniture stores, deliberately down-market bars, and a stretch of chic restaurants. Squeezed in between are the old fixtures, an autobody shop here, a cheap pho restaurant there, and, announcing itself with a crisp black awning, a swingers’ club called Wicked, where “it’s good to be naughty.” The area is vibrant, populated by what urban affairs guru Richard Florida would call “the creative class,” stylish young people in skinny jeans, affluent parents piloting designer strollers, and bearded gourmands with fervent opinions about coffee. Back in 2007, Toronto Life magazine declared it “a neighbourhood on the verge.” In the six years since, it has definitely arrived.

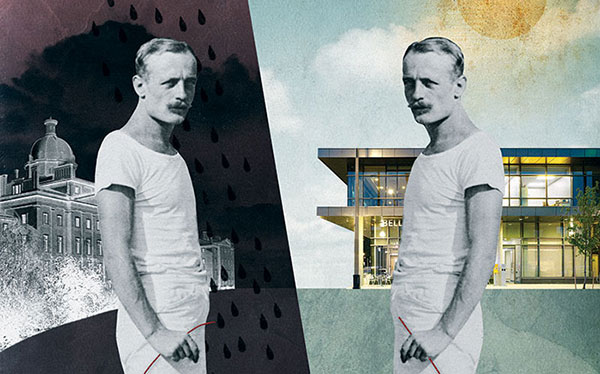

On the south side of Queen Street, running a few blocks to the east and west of Ossington, lies the most dramatic transformation, an eleven-hectare development on the site of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, the country’s largest teaching hospital and research centre in the field. In 2001, CAMH announced what has become a twenty-year capital project to improve the site; to date more than $108 million has been raised in private donations. The plan builds on two pillars of contemporary thinking about mental illness: neuroscience research, and the integration of patients into communities and workplaces.

Last September, I met with psychiatrist David Goldbloom, CAMH’s senior medical adviser, for a tour of the campus. An energetic man in his late fifties, he kibitzes with colleagues as he strides through the property, and later launches a discussion about neuroscience by quoting Woody Allen’s line from Sleeper about his brain being “my second-favourite organ.”

The initial phases of construction are complete, with new residences for those with mood disorders and addictions, a ward for psychiatric patients who have committed crimes, and a centre for geriatric and pediatric care. Before taking me into the latter, Goldbloom tells me CAMH doesn’t have a gift shop. It seems like an odd detail to relate, until he explains the significance: patients here don’t receive many visitors. The new design—large windows, soft chairs and couches arranged in small groups, and a patio outside with tables and benches overlooking a playground and a basketball court—aims for a more welcoming feel.

The next phase includes a complex that will house a theatre and a gallery, and a unit dedicated to patients with schizophrenia. The remainder of the campus is devoted to commercial, non-hospital properties: a drugstore, a bank, a daycare, a café staffed by patients, and affordable rental housing. The sheer scale is remarkable; the entire facility covers nine city blocks. Once it is complete, the mental health centre, with its elegant, modern design and pretty parkettes, will become a defining feature of the neighbourhood.

Goldbloom leads me into one of the residential buildings. It is airy and light-filled, like a cheerful Scandinavian budget hotel. Large windows in the common areas frame views of an inviting courtyard. Squint a little, and you could be in a model suite for one of the nearby condos. The institutional touches are discreet. Staff deliver meals to the units, but each one contains a shared kitchen for clients (the preferred term at CAMH), where they can cook if they choose. Everyone has a private room and a bathroom and windows that open for air—but not too wide. Similarly, hooks and bars are designed to collapse if too much weight is put on them.

In the lobby of the nearby Bell Gateway Building, which houses outpatient programs and administration offices, Goldbloom pauses before a wall displaying high-profile donors. The facility was named in 2011 to recognize Bell Canada’s $10-million donation, the largest corporate gift to a mental health cause in Canada. A decade ago, he tells me, this would have been unimaginable. No one wanted to be associated with mental illness. Nor would so many public figures, such as broadcaster Valerie Pringle or Olympian Clara Hughes, have signed up as spokespersons for the cause.

Mental illness today, as reflected in CAMH’s sleek redevelopment, smack in the middle of Toronto’s hippest neighbourhood, has never looked so mainstream. Advances in neuroscience have lent popular credibility to psychiatry, a field not so long ago considered medicine’s poor relation. A new candour among people with depression, addictions, and anxiety has provided a relatable face for the cause.

To appreciate just how radical this is, you need only look at CAMH’s predecessors. Mental health facilities have existed on this spot since the Provincial Lunatic Asylum opened its doors in 1850. In his moving historical study, published in 2000, Remembrance of Patients Past: Patient Life at the Toronto Hospital for the Insane, 1870–1940, Geoffrey Reaume, an associate professor of critical disability studies at Toronto’s York University, tells the story of 197 patients who lived at the hospital in its early years. It performed an essential function, he writes, but the setting for most inmates was “cold, crude, and harsh”—overcrowded, infested with vermin, stifling in the summer, and bitterly cold in the winter. Some psychiatric disorders were considered intractable, and treatments were rudimentary. An imposing five-metre-high brick wall, built mainly by male patients (unpaid labour was seen as a form of therapy), encircled the property, as much to keep rubberneckers out as to keep the inmates in.

Later facilities were no less foreboding. In the ’60s, ugly, blocky structures replaced the original asylum. Following the mass deinstitutionalization of psychiatric patients in the ’60s and ’70s, former residents found themselves living on the nearby streets or in bleak local rooming houses. Near the end of our tour, Goldbloom takes me into one of the old residences from that era, still in use but slated for demolition. The dark lobby has low ceilings and heavy doors; overhead fluorescent lighting casts creepy shadows. Torontonians of a certain age remember being disciplined as naughty children with the threat of being sent to 999 Queen Street, the same way other kids were ordered to clean their plates because of the starving children in Africa.

In 1979, the facility, then called the Queen Street Mental Health Centre, symbolically changed its address to 1001 Queen Street, to dissociate itself from the past. A few sections of the old asylum wall still border the property, maintained for their historical value, a reminder of a time when most people thought of those inside as deficient and apart. In contrast, the hoardings that bordered the new construction site on the day I visited trumpeted the slogan “Where being part of the community is part of the treatment.”

Dismantling the moral judgments and fears that have persisted throughout human history proves to be a more Herculean challenge. For so many centuries, psychiatric problems were attributed to everything from demonic possession to feeble-mindedness, not to mention rotten mothers. Even as some conditions, such as milder forms of depression and anxiety, have become almost benign in the cultural consciousness, other manifestations of mental illness, like severe psychosis, remain foreign and frightening. In December, as I was writing this, a brief story appeared in the Toronto Star about a missing CAMH client described by police as “a danger to himself and others.” Then came the news of the mass murder in Newtown, Connecticut, in which twenty young children and eight adults were shot and killed. Alongside discussions about gun control was speculation about the killer’s mental state, once again raising the spectre of mental illness as an explanation for deviant, deadly behaviour. (People with mental illness, it should be noted, are far more likely to be victims of violence than perpetrators of it.) Rooting out age-old prejudices appears just as crucial as research into causes and treatments. The best way to do this, though, remains a matter of some debate.

For CAMH’s part, Goldbloom explains, the plan is to utterly erase the demarcation between CAMH and the rest of the city—and, implicitly, between “us” and “them.” The goal, he says, “is integration, to defang an issue that has been a huge threat to people.”

In his lively and opinionated book A History of Psychiatry: From the Era of the Asylum to the Age of Prozac, University of Toronto historian Edward Shorter writes, “Psychiatry has always been torn between two visions of mental illness. One vision stresses the neurosciences, with their interest in brain chemistry, brain anatomy, and medication, seeing the origin of psychic distress in the biology of the cerebral cortex. The other vision stresses the psychosocial side of patients’ lives, attributing their symptoms to social problems or past personal stresses.” Whichever view holds sway in a given time and place has significant implications for how those with mental illness are treated and perceived.

I raise the question of these competing approaches with Arun Ravindran, clinical director of the mood and anxiety disorders program at CAMH. He pauses before answering. Soft spoken and temperate, he is a clinician with eclectic research interests who recently completed a study on the benefits of yoga (which may be comparable to those of antidepressants) on people with depression. Schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, and addiction are widely understood to have a genetic component. However, he adds, “most sensible people in the field would say the causes of mood disorders are multifactorial. Genes have a huge influence, but environment, developmental issues, and childhood adversity all contribute.”

While environment and experience are understood to play a role, the neuroscience model is undeniably ascendant. At CAMH, neural circuitry and brain plasticity have been a major research focus, and one of the redevelopment’s marquee facilities is the Campbell Family Mental Health Research Institute, launched last year with a $30-million private donation. A 2011 Globe and Mail story about CAMH’s fundraising campaign suggested that one factor in its success was the growing acceptance of a biological basis for psychiatric illnesses, many of them treatable with medical intervention.

The biomedical frame is by no means new. Hippocrates attributed emotional and psychological disorders to an imbalance of the humours. In the modern era, Emil Kraepelin, the pioneering German psychiatrist who first diagnosed schizophrenia in the 1880s and later named Alzheimer’s disease, conducted early research in psychopharmacology and laid the groundwork for the classification and categorization of psychiatric disorders.

Recently, inventions such as positron emission tomography (PET) scans, functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and the mapping of the human genome have opened up our cognitive processes to ever-greater scrutiny. And as results from the laboratory, however preliminary and embryonic, have insinuated themselves into the public consciousness, the study of the brain has become irresistibly sexy. Through viral video TED talks and business class bestsellers, neuroscience and its siblings, behavioural psychology and the somewhat dubious evolutionary psychology, have become a lingua franca, deployed to explain our failed diets and gambling habits, our voting patterns and dating choices.

Is it any wonder that neuroscience is so appealing? As a way of understanding who we are, it provides a neat fix for what feels most irrational and inexplicable: our emotions and temperament. And when it comes to the paralyzing emptiness of depression, the heart-thudding adrenalin of anxiety, or the unbidden inner voices of schizophrenia, neuroscience provides hope that these terrifying symptoms might be stilled. Consider the evolution of the psychoactive drugs that began to be prescribed in the ’50s, and exploded into widespread use following the release of Prozac in the late ’80s. By 2008, psychotherapeutic drugs stood second only to cardiovascular medication in dispensed prescription volume in Canada. Millions of lives have been stabilized and saved, and mental illness is now conceived by many as a condition, not unlike diabetes or high cholesterol, that can be managed by modern medicine.

Lately, however, the infatuation with neuroscience has come under interrogation. The phrase “brain porn” is used to describe the dazzle power of scientific theories about human behaviour. A 2012 British study that investigated how the media covers neuroscience revealed how eagerly and poorly it has taken up brain research, reducing intricate studies to grabby headlines about “a faithfulness gene” that could prevent us from straying, or the “Mozart effect,” an unsubstantiated theory that exposure to classical music makes kids smarter.

The problem, Goldbloom observes, is that neuroscience is “infused with enthusiasm and overburdened with expectation.” As with other areas of medicine (think of the protracted advances in cancer and AIDS research), progress in neuroscience moves in stutter-step. The brain is exquisitely complicated, and scientists are nowhere close to cracking its mysteries. “Can we see things in new ways in the brain that we didn’t twenty years ago? ” Goldbloom asks. “Yes. Have we pinpointed the cause of any one mental illness? No.”

Against these vagaries of research, a critique is commonly voiced. In the quest to fashion mental illness as a medical condition, the net has been cast too wide. Serious questions about the efficacy and safety of psychoactive drugs are overlooked. Critics, many of them psychiatrists and physicians, warn that pharmaceutical companies have a big, fat thumb on the scale; medications are overly relied upon and over prescribed, with potentially dangerous consequences. The side effects of some psychoactive drugs can lead to suicidal thoughts and actions.

In the matter of stigma and public opinion, another hazard comes into focus. It has been assumed that the biogenetic model of mental illness might also further the anti-stigma cause. Intuitively, it makes sense: if psychiatric disorders are hereditary, then how could those who are afflicted by them be seen as responsible for their condition?

Research, however, has revealed a more complicated response. Studies indicate that when respondents believed that depression or schizophrenia had a genetic cause, they tended toward leniency in punishing people with these conditions who had transgressed. At the same time, those surveyed saw mental illness as immutable and fixed; because it was inborn, it would not get better. As a result, they wanted less contact with mentally ill people and their siblings, believing relatives to be at risk as well. Rather than generating empathy, the genetic view of mental illness led to a desire for greater social distance.

So, a paradox. Medicalizing conditions such as schizophrenia and depression may help in raising awareness and funds, and make it easier to seek and receive help. The trouble, it seems, is that framing these illnesses as genetic may inadvertently lead us to view people with such disorders as inherently damaged. This suggests that even as we have become more accepting of mental illness as a disease, we are not yet comfortable with those who suffer from it.

In the opposite corner—about as opposite as you can get—is the psychiatric survivor movement, also called Mad Pride. It is a big tent. Some oppose the practice of psychiatry altogether and advocate little or no intervention for conditions such as schizophrenia (many are skeptical that it even exists); others simply want patients, or “people deemed mad” (the term often preferred by Mad Pride), to be more fully consulted and engaged in research, treatment, and public awareness.

Most advocates under the tent, though, remain leery of the biomedical model for mental illness, and with good reason. In the past, this approach has led to some of the worst atrocities in the history of medicine: forced lobotomies; eugenics; and the sterilization of mentally disabled people (in Alberta, the 1928 Sexual Sterilization Act stayed on the books until 1972, and a reported 2,822 people were operated on during that time).

Geoffrey Reaume has schizophrenia and was institutionalized as a teenager. He does not oppose treatment, or even the use of medication, for those with psychiatric disabilities (a term he prefers to “mental illness”). Instead, he is concerned that some treatments can be used as a form of social control, a way to mute individuals who are different. (Take psychiatry’s attitudes toward homosexuality, for example. What is now viewed as a normal aspect of human love and desire was thought, only decades ago, to be a pathology. Homosexuality was not entirely excised from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders until 1986.) “I’m not romanticizing mental illness,” Reaume says. “There is genuine anguish and suffering. But madness can sometimes be a legitimate response to an unjust society.”

Bonnie Burstow, a professor at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education in Toronto, takes a more radical position; she opposes psychiatry altogether. During our interview, because she has back problems, she lies on a chaise longue, the only way she can sit comfortably. She looks imperious but seems quite warm, and she fusses gently over arrangements with the graduate student who has wheeled the chair into our meeting. Then she issues a challenge. As an experiment, one she routinely conducts with her students, she asks that I avoid using any medical language during our conversation. So it is not “mental illness” or “psychiatric disorder,” but rather “human troubles” or “difficulties.” Her point is to illustrate how much the biomedical model has shaped our understanding of our emotional and psychological states. I found the experiment illuminating and frustrating in equal measure.

Psychiatry aims for conformity, Burstow says. “We live in a world that doesn’t tolerate difference. What people call ‘mental illness’ can be a spiritual crisis with insight within.” Noting the higher rates of depression among women, for instance, she says they are not unhappy because of their brain chemistry; they are unhappy because they live in a sexist culture.

The Mad Pride movement has been compared to Deaf activism, which rejects the idea of deafness as a disability, seeing it instead as a cultural and linguistic identity. But it also reminds me of queer activism in the early ’90s, which was defined by combat boots, kiss-ins, outings of public figures, and a resistance to the genteel, ingratiating political tactic of winning equality by appearing as straight and unthreatening as possible. In each of these movements, the aim is not to adapt to suit society, but rather to expand notions of what counts as acceptable.

Elsewhere, you find more moderate strains of the Mad Pride position in the sentiment that psychiatry has pathologized the human condition, turning ordinary nervousness, shyness, and grief into disorders. Allan V. Horwitz and Jerome C. Wakefield have examined the expanding criteria for diagnosis of depression and anxiety in their books The Loss of Sadness (2007) and All We Have to Fear(2012). In a 2008 interview with Scientific American, they noted, “Before 1980, only symptoms that were ‘excessive’ and inexplicable relative to their provoking context were considered to be signs of a depressive disorder. After 1980 all symptoms, even those that are proportionate to their provoking cause, were defined as disordered.” Ethan Watters, author of Crazy Like Us, has reported on the influence of Western ideas about mental health in the developing world, a kind of colonization of the psyche and spirit. American understanding of health and mental illness, he says, is “homogenizing the way the world goes mad.” A recent story in New York magazine called out the modern tendency to attribute nerdy personality tics like social ineptitude, obsessiveness, and narcissism to Asperger’s syndrome. The growing list of measures used for a spot on the autism spectrum, writes Benjamin Wallace in the article “Are You On It?,” has created a “fuzzy, ever-shifting threshold where clinical disorder shades into everyday eccentricity.”

How mental illness is defined and diagnosed has material implications for insurance coverage, drug benefits, human rights provisions, and the justice system. But in an unlikely bedfellows way, the aims of bodies such as CAMH and the rallying cry of psychiatry skeptics are not so different. Both want greater tolerance and understanding. One seeks to remove stigma by naming the disease, the other by limiting what we consider a disease. At the crux of these debates, about the nature-or-nurture roots of psychological suffering and the merits of diagnosis versus the tyranny of labels, sits the question of what “normal” means. Most of us can grasp the difference between major depression, what Winston Churchill so vividly described as a “black dog,” and a passing case of the blues. It is tougher to distinguish the point at which the blues tip into actual depression, fear becomes anxiety, and excitement turns into mania.

In September 2010, neurologist Catherine Zahn, CEO and president of CAMH, gave a TEDx talk in Toronto, where she discussed the latest developments in the study of brain function, and then described her personal connections to mental illness, which included a brother-in-law in recovery from addiction, and grandparents who worked in a mental hospital. It was a feel-good presentation, meant to incite and inspire, but it carried a decidedly provocative title, “We Are All Mentally Ill.”

Are we? Consider the statistics. One in five Canadians will experience a mental illness in his or her lifetime, and the other four will know someone who does. Anxiety and depression are among the top five reasons for visits to the doctor. Mental illness is the second most prevalent cause of disability and premature death; as a nation, it costs us an estimated $51 billion annually in health care and lost productivity costs. Globally, depression will be the single biggest medical burden by 2020, according to the World Health Organization.

Despite the numbers, very few of us receive treatment or care; in Canada, only one-third find the support they need. For children and young adults, the situation is dire. Although many mental illnesses have their onset in adolescence, and suicide is the second most common cause of death for this age group, 40 percent of teenagers with depression never access mental health services.

In the debates over what is or is not a disorder, this state of affairs often gets overlooked. Arun Ravindran explains that his primary concern is not that people are over diagnosed or overmedicated, but that those who are in pain receive no help, or not the right kind. In addition to his work at CAMH, Ravindran also serves as director of global mental health affairs at U of T, and spends a month every year in the developing world, where he has seen people with mental illness chained up and living in squalor. From the table in front of him, he picks up a folder containing documents from an internal inquiry into a recent suicide. The young man had been treated for severe depression for months, and the doctors tried everything to make him well. Nothing worked.

The mainstreaming of mental illness suggests a partial solution. Surely it will lead to more people seeking help, and more money and support for Ravindran’s most marginalized patients. Already, we are becoming familiar and comfortable with these diseases. One critically adored television show at the moment is Homeland, which stars Claire Danes as a CIA agent with bipolar disorder. And at a multiplex near CAMH, three Oscar-bait movies, Flight, Lincoln, and Silver Linings Playbook, feature major characters suffering from addiction, depression, bipolar disorder, or obsessive-compulsive disorder. These fictional images have been matched by insightful memoirs about real-life struggles with mental illness: Mary Karr’s Lit, William Styron’s Darkness Visible, Andrew Solomon’s The Noonday Demon, and Kay Redfield Jamison’s An Unquiet Mind.

It has become common to have an acquaintance discuss her postpartum depression, or to have a friend share the news that his child is in counselling for an anxiety disorder, or to learn that a neighbour follows a twelve-step program. One measure of how far we have come is the relatively open acknowledgement of the incidence of post-traumatic stress disorder among soldiers who served in Iraq and Afghanistan, compared with the near-silence met by struggling Vietnam vets a generation ago.

But a mainstream vision of mental illness still has its limitations. According to Lisa Brown, a former psychiatric nurse and the founder and executive artistic director of Workman Arts in Toronto, many of us make a distinction between the tormented genius and “the person on the street talking to God.” One is romantic, the other crazy. Her organization, which is affiliated with CAMH, supports artists with mental illnesses and addictions, and provides them with studio space and professional mentors. People often assume that the work produced in her program must be amateurish—art therapy, not real art. This is a surprising bias, given the number of great masters (Vincent van Gogh being perhaps the best known) who suffered from psychological disorders, as well as the mounting research that suggests a correlation between creativity and mental illness.

The conversation turns to the question of how certain expressions of mental illness are more stigmatized than others. The composed, neatly dressed types depicted on public awareness and fundraising campaign posters stand worlds apart from the troubled folks sleeping on benches and cadging cigarettes on the CAMH campus. Hope for them remains a glimmer. One promising initiative is At Home/Chez Soi, a five-year, $110-million project run by the Mental Health Commission of Canada that wraps up this spring, and has placed hundreds of homeless people with mental illness into safe, stable living situations.

“Do I associate myself with the person on the street talking to God? ” Brown asks. “No, but I could have ended up there.” Six years ago, at forty-four, she began to have difficulties at social events and felt anxious when she had to leave home. She was frightened to talk to others or speak in front of a group. She had always been a worrier, but this was different. She didn’t feel in control of her own mind. She began to drink more. Eventually, she consulted a doctor, who prescribed medication. “Within three days,” she says, “my anxiety dissipated.” She can’t imagine coping if she had remained in her previous state.

The possibility that any of us could lose control of our thoughts, emotions, and perceptions of reality lays bare our most profound fears. Unlike other disabilities, conditions that affect our mind affect our deepest sense of self, our core. Catherine Zahn’s diagnosis that “we are all mentally ill” is not just a zippy slogan. The toughest battle is not in convincing us that we are all in this together, but rather in asking us to acknowledge that we are all so very fragile and vulnerable. That there is, in the end, no “us and them” at all.

Before my tour with David Goldbloom, I stopped for tea in the Out of This World Café, on the main floor of the Bell Gateway Building. The small restaurant sells sandwiches, soups, and drinks and is staffed by CAMH clients. There are several neighbourhood coffee shops nearby, from the indie cafés on Ossington to the multiple Starbucks on Queen. But the place was full, mainly with CAMH staff, visitors, and people who might be clients. The woman who served me was painstaking in her attention, reading me all of the ingredients in every tea on offer. It took several minutes, but no one waiting behind me complained.

After I got my drink, a man entered the café in a wheelchair, cutting to the front of the line. It was a cold day, but he was barefoot, and his clothes and beard were dirty. He was agitated and muttering loudly. There was a brief, slightly nervous pause in the noisy room. Then the woman who had just served me took control. She tended to him with the same level of care, interpreting his mumbled order, fishing into his pocket for his money and slowly counting it, then carrying his coffee to the table he pointed to outside. Everyone waited as she served him. Coffee in hand, he settled down to drink it. She returned to the cash register and took the next order. It was nothing more than a small moment of kindness and grace. But in this gentrified corner of the busy, changing city, it was its own kind of revolution.

This appeared in the March 2013 issue.