On the wall of my kitchen hangs a print of a William Kurelek “pot boiler,” the dismissive term he used to describe the folksy studies of childhood innocence that made him one of the most successful and celebrated Canadian artists of his generation. My potboiler—a pleasant late-afternoon scene of children tobogganing in Toronto’s Don Valley—displays the deceptively casual Kurelek mastery of composition and tone. The bluish light of the darkening sky reflects off the snowy valley, building an insulating glow that wraps the scene in claustrophobic comfort. In the foreground, a line of snowsuited racers crouch over sleds and twist their heads toward a boy in yellow, his arm raised to signal the start. Down in the valley, children careen and collapse in a sprawl of spidery limbs. A row of dishevelled Victorians gaze on benignly from the distant road, as if waiting to receive the tobogganers at the last of the light.

Kurelek’s commercial success was built on sweet scenes like this. The most iconic drew on his memories growing up on the Prairies during the Great Depression. As a young man, he fled farm life for the city but took the work ethic with him. For much of the 1960s and ’70s, he toiled with furious intensity and industry: limiting himself to five hours of sleep, he could dash off as many as three paintings and drawings a day, leaving a legacy of more than 2,000 works. He mounted dozens of exhibits, oversaw massive print runs of his art, produced several documentary films, and created illustrations for books such as W. O. Mitchell’s Who Has Seen the Wind. He also produced eleven books of his own, two of which, A Prairie Boy’s Winter and Lumberjack, won the New York Times award for best illustrated children’s book of the year. In 1973, Robert Fulford described Kurelek’s youth as “the most copiously illustrated boyhood in recent Canadian history.”

A different Kurelek is found in such works as Our My Lai, the Massacre of Highland Creek (1972). At first glance, it appears to be just another winter landscape: the melancholic slope of snow-covered valley, the thin band of overcast heaven. A modern white tower broods over a snow-lined creek that flows past a clutch of spare evergreens. Then you notice the garbage cans. Marked “Hospital Waste,” they line either side of the creek and overflow with the sick pinkish-red of aborted fetuses. Blood stains the water, spilling off the canvas and onto the frame. A devout Catholic, Kurelek painted such sermons of wrath for what he considered an ungodly world. Early in his career, he announced to a friend his desire to paint religious “propaganda,” a term he used in a positive sense. He lived like a monk, fasting for days at a time, and working for seventeen hours at a stretch with breaks for daily Mass and the occasional cup of coffee. He cramped his body into a tiny basement studio six feet by four feet, a converted coal cellar ornamented by a life-sized crown of thorns, where the noxious fumes from his paints burned his lungs and left him spinning with headaches.

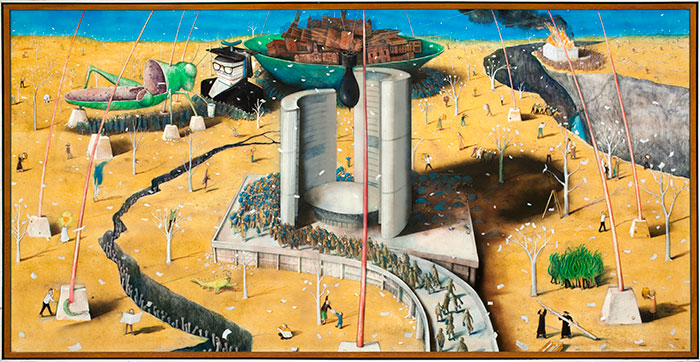

Perched in his cell like a latter-day John of Patmos, he channelled revelations of human civilization’s imminent destruction, as in the immolation of the entire city of Hamilton, Ontario, imagined with hellish detail in This Is the Nemesis (1965). His sequence of works depicting the crucifixion of Christ—160 in all, one for each verse of St. Matthew’s Passion narrative—looked back to the late medieval devotion to blood and wounds, and anticipated the forensic blood spatter of Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ.

To a public bemused by his strong religious convictions (one interested buyer said he would gladly purchase one of Kurelek’s landscapes if the artist would simply paint out the mushroom cloud), he responded clearly, “No religion: No Kurelek. And no Kurelek: No farm paintings.” He hoped eventually to devote himself entirely to religious subjects. But he remained a pragmatic prophet, striking a deal with his Toronto art dealer, Avrom Isaacs, to alternate one exhibit of “secular” works with each religious one.

In the fashionable circles of art criticism in the countercultural ’60s, he was a divisive figure. During the lead-up to the Cuban Missile Crisis, the critic Elizabeth Kilbourn praised his “terrifying vigour,” singling out Hailstorm in Alberta (1961) as “an image of chaos and doom in an age of doomsday diplomacy.” Four years later, in a memorable critical assassination, Harry Malcolmson denounced a Kurelek show as “full of horrid sights”; the works, he wrote, were “so grotesque and exaggerated…they might have been painted by some other artist satirizing Kurelek’s moral earnestness.”

William Kurelek: The Messenger is the first retrospective of his art in a quarter century and the largest ever mounted. A partnership between three institutions, the exhibit opened at the Winnipeg Art Gallery in September 2011 and travelled to the Art Gallery of Hamilton, and finishes its run at the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria this summer. Curated by Mary Jo Hughes, Tobi Bruce, and Andrew Kear, it collects over eighty works, paying particular attention to the artist’s early formative period in London, UK, in the ’50s, when he underwent psychiatric treatment and conversion to Catholicism.

Like every critical appraisal, the exhibit grapples with a variant of the same problem: that there seemed to be not one but two William Kureleks. There is the Pied Piper of prairie life, and then there is the crank whose unsettling visions of modern excess earned him comparisons to Bosch and Bruegel the Elder. But how we frame the Kurelek problem conceals assumptions about the nature of the modern project, assumptions that have come under increasing scrutiny in the thirty-five years since his death in 1977: that strong religious convictions are aberrant in modern life, especially among artists, for whom art supplies a surrogate piety. Along with his philosophy of art, Kurelek’s life story—his conversion from atheism to faith, from skepticism to certainty, from psychotherapy to confession—reads as a fascinating counter-narrative to those of other twentieth-century artists and writers, such as Samuel Beckett and James Baldwin.

By restoring religion to centre frame, the exhibition attempts to rephrase the question. As the curators write in a press release, “Kurelek was at his best and most challenging when he successfully bridged the pastoral and the prophetic, combined memory and message.” Rather than dismissing his religious sensibilities as idiosyncratic, the show conveys his prescience: the global renaissance of apocalyptic, conservative faith and attendant culture war. The problem of Kurelek is not how to reconcile his seeming contradictions of sacred and secular, but whether there was ever a contradiction to resolve in the first place.

Kurelek’s early life was characterized by failure and rejection. Born in 1927 to Ukrainian parents in Alberta, he bore the brunt of his father’s anger whenever he lost track of the cows or had trouble working machinery. An outcast at home and school alike, he fled the farm for high school and university in Winnipeg. Following graduation, he enrolled at the Ontario College of Art in Toronto, but dropped out in his first year, disappointed with the creative environment. Next came a scholarship to study art at Mexico’s Instituto Allende, home to muralist Diego Rivera; but, disenchanted by the air of artistic tourism among the students, Kurelek left there, too.

In 1952, still running at twenty-five, he tried exile in London. Suffering from extreme depression and chronic eye pain, he committed himself to the Maudsley Hospital and was diagnosed with depersonalization, a condition he described as a “trance handicap” that left him feeling that “reality was not concrete enough…to be convincing.” After a spell of Freudian psychoanalysis, he moved on to the Netherne psychiatric hospital, where Edward Adamson, a pioneer in art therapy, prompted him to paint his pain. He happily obliged, spinning out a series of nightmarish works, such as I Spit on Life (1953–54), a bulletin board arrangement of scenes from his life: suffering bullies in the schoolyard and stinging rebukes at the dinner table from his parents, whom he represented with forked tongues. Tobi Bruce, in a fine essay in the exhibition catalogue, describes the work as “part memory, part self-analysis, part exorcism.” As a love token, Kurelek gifted the piece to an occupational therapist, Margaret Smith, then swallowed eight sleeping pills and slashed his arms and face with a razor blade in a failed suicide attempt. Fourteen treatments of electroconvulsive therapy followed, leaving him dazed, disoriented, and suffering significant memory loss. It was “like being executed fourteen times over,” he wrote.

But this also set the roots of a rebirth. Restored to a degree of mental equilibrium, he moved out of Netherne and continued treatment as an outpatient. He earned money by painting trompe l’oeils, hyperrealistic still lifes of coins, stamps, and dollar bills so detailed they create the illusion of reality—a bit ironic, considering his inability to establish solid emotional connections with actual people or objects. Indeed, the exquisite works, several of which are on view in The Messenger, suggest a kind of spiritual discipline. Art had already become much more than a tool of survival or self-therapy for him. By paying attention to the outside world in its humble particulars, he may have learned to love it.

At the time of his attempted suicide, he was already interested in Roman Catholicism, spurred on by his friendship with Smith. His conversion narrative resembles the halting, rational peregrination patterned by Augustine’s Confessions. While in London, Kurelek wore down priests with probing theological questions, a restless urgency to establish proof of God’s existence. Two encounters sealed the deal: the rigour and eloquence of Thomas Aquinas’s systematic theology calmed his skeptical mind, and a pilgrimage to Lourdes warmed his restless heart. His eye pain vanished, the depression receded, and he felt a moral urgency to heal the rift with his father. The prodigal had come home.

While Kurelek recounts the entire conversion in his 1973 spiritual memoir, Someone with Me, the tale is best told through his remarkable self-portraits from the period, on view in The Messenger: Lord That I May See (1955) shows him kneeling in the foreground like a beggar, one arm grasping the air in supplication, head rolled back, with two flesh-coloured divots where the eyes should be. Two years later, in Self-Portrait (1957), he gazes confidently at the viewer, like a Byzantine icon. Behind him, a painting of Virgin and child, postcards of Lourdes and the Shroud of Turin, and a quotation from Augustine’s Confessions testify to his resurrection: “Late have I loved you, O Ancient Beauty, ever old and ever new.”

Like any apostle worth his salt, Kurelek diagnosed the world with the same affliction that once crippled him: the modern age suffered from disenchantment and depersonalization. As Andrew Kear notes, Kurelek cribbed much of his critique from Father Edward Holloway, one of the priests he dogged in the years leading up to his conversion in London. Holloway’s Catholicism: A New Synthesis, published in 1969, joined a broader conservative wave of Catholic and Protestant resistance to the postwar privatization of religion and the decline of Christian cultural influence. However, while the angry evangelicals of the 1970s saw in Communism the font of all evils, Kurelek’s politics transgressed the bounds of secular left and religious right. His seven deadly modern sins included abortion, but also greed, environmental destruction, poverty in the developing world, and nuclear aggression. In Light Trading Day, Toronto Stock Exchange (1971), traders go about their business, oblivious to the crown of thorns tucked discreetly in the corner. Cross Section of Vinnitsia in the Ukraine, 1939 (1968), on the other hand, splits the picture horizontally between a pleasant scene of children and adults dancing and picnicking in a leafy park, and the subterranean cross-section of mass graves beneath their feet.

However he may have mimed Holloway’s theological conservatism, Kurelek’s convictions were nurtured by personal experience. After returning to Canada, he worked briefly at a tile plant in Grimsby, Ontario, and recalled rushing into a fiery kiln to carry out burning tiles with his bare hands, “a foretaste of hell,” he wrote, “like something out of Bosch.” Indeed, by the early 1960s, the great masters of medieval art—Bosch, Bruegel, and Van Eyck—became increasingly central to his vision. He praised the anonymous sculptors of the great European cathedrals, who carved figures high above the ground for the eyes of God alone; he charged the Renaissance with turning art into an idol and making man the measure of all things, “the trend,” he wrote, “that has continued to this day.”

In protest, he sought to assert the artist’s place in the great chain of being. He refused to sign his paintings (a compromise was eventually reached with his agent, in which Kurelek agreed to employ the monogram “WK,” topped by a cross). Imitating the medieval guild, he employed assistants to work on his larger pieces. His monkish habits—fasting and punctuating his work cycle with disciplines of prayer and meditation on Scripture—set him apart from the bohemian lifestyles of many contemporary artists.

Still, to cast him as essentially medieval in outlook may be too much gilding on the picture frame. While he assailed the egotism of the Renaissance, his ego was as strong as they come. And despite his conversion, he did not bow meekly to papal authority. He hated the gaudy affluence of Rome; more significant, his apocalyptic views depended on an idiosyncratic interpretation of Biblical prophecy that diverged sharply from traditional Church teaching. His artistic style in part owes a debt to social realists such as Rivera, and the modern technology of photography. If anything, Kurelek’s critique resembles the romantic rage of William Blake: the eschatological immediacy and prophetic vision, the white-hot fury at the depersonalizing thrust of industrialization and Enlightenment reason, the dialectical play of innocence and experience. Kurelek’s neo-medieval turn was highly self-conscious, individualized, and freely chosen against a flurry of possible options. In other words, it was an expression of his modernity.

One solution to the Kurelek conundrum has trumpeted the safer virtues of his “memory” paintings—the democratic accessibility of his folk-primitive style, the nationalist sweep of his vast prairie landscapes, the multicultural makeup of his subjects—while muting the notes of conservative critique. But cleaving him into his secular and religious selves, the crackpot prophet and the misty-eyed dreamer, has always been deeply dissatisfying; it makes it impossible to see him as he saw himself, as a painter with an integrated vision of the purpose and practice of his craft. For him, there could be no potboilers without the prophetic. Indeed, what an earlier generation of critics and connoisseurs mislabelled as schizophrenia, a newer generation sees as fruitful friction.

The movement from doubt to certainty did not free Kurelek from suffering, but from the meaninglessness of suffering. Restlessness and alienation were not lifted but transfigured. This sweet sadness is ultimately what unites the vast and variegated body of work assembled for The Messenger. The secret spring that connects the tobogganing scene in my kitchen painting and the bloody creek in Our My Lai has less to do with message or audience than with a conception of the human condition, a pervasive melancholy rooted in the Augustinian conviction that the heart is restless until it rests in God.

The natural world for Kurelek was not the repository of magic and meaning it had been for the romantics or the transcendentalists. Wilderness, that surrogate sanctuary for modern poets and artists, did not invite and enchant. He set his figures adrift in vast deserts of prairie and forest, leaving them alienated from their surroundings and from one another. Nature was hostile and forbidding, a place of spiritual temptation, contest, and attrition. He deepened the sense of unease by typically choosing a point of perspective in an intermediate zone six to nine metres off the ground. In works such as No Grass Grows on the Beaten Path (1975), the viewer feels suspended somewhere between heaven and earth, as if peering down on a stage from a balcony, or perched atop a tree branch, or hanging from a cross.

The “Big Lonely”—a colloquialism for the vastness of the Canadian West, which Kurelek borrowed for one of his painting series—comes close to a summation of his complex attitude toward nature. The title of another work, Nature: Beautiful, but Heartless (1976), is even closer. What these post-conversion landscapes reveal is how much of his pre-conversion sense of alienation remained intact. The balm he found at the grotto of Lourdes and in the writings of Thomas Aquinas could not heal the existential wound of being. In his memoir, he confesses that he felt most at home in landscapes seemingly devoid of spiritual presence, such as a bog: “It speaks to me because it is flat and it is lonely, as I often was and sometimes still am.”

Such confessions were rare for Kurelek, who trusted others haltingly. Yet if pain was, as his biographer Patricia Morley claims, his “constant companion,” it may explain why we still puzzle over his paintings. His best work plays through the major and minor chords of joy and grief, a tension that saved his nostalgic work from sentimentality and his darker visions from nihilism. As propaganda, it fails. As honest testament to a wounded, restless heart, it mimes the modern condition.

This appeared in the June 2012 issue.