It was the tiny, brown birthmark near the pupil of his right eye that gave Yehuda away. We were on a windswept hilltop not far from Jerusalem in the West Bank outpost of Amona. Chaos erupted all around us when Israeli soldiers clashed with nearly 2,500 protesters resisting any attempt to remove Jewish settlers and demolish their homes. Arieh Eldad, a right-wing parliamentarian, was taken away on a stretcher; Effie Eitam, another member of the Knesset, bled profusely (he said that his skull had been clipped by the hoof of a police horse). Hundreds of young men, dressed like Yehuda in loose-fitting shirts and sporting shoulder-length sidelocks, staggered about, their faces covered in blood and tears. Throughout the melee, Yehuda stayed calm, occasionally leaning against a bulldozer and considering getting in front of it—showing an angry determination that I first saw in him during a protest in Hebron in late January.

During that confrontation, Yehuda’s face was concealed in a mask made of bandages; only his emerald-coloured eyes shone through the slit in the disguise. Yehuda was in Hebron to help settlers stop the evacuation of the Kasbah at the entranceway to the city, and just across from the Tomb of the Patriarchs, one of Judaism’s holiest sites. He had been defending the settlements on the West Bank since August 2005, when Prime Minister Ariel Sharon pulled settlers out of the Gaza Strip. At that time, he was a student at a seminary in the Golan Heights, and along with almost 1,400 other young men he followed their rabbi’s instructions and travelled to Gaza to stand vigil. Yehuda was expecting something miraculous to happen because a week beforehand, and for as long as he could recall, the rabbi had declared that the settlers would never be removed, that God would come down in a pillar of fire and that the Lord and his angels would intervene on their behalf.

Neither God nor his angels arrived, and on the fourth day of the campaign Yehuda was dragged off to prison. He felt the rabbi, who was both his mentor and a father figure, had lied to him and he considered taking his own life. So perhaps it’s not surprising that Yehuda no longer consults a rabbi before confronting the Israeli army. Instead, he has joined Noar Hagvaot (HilltopYouth), a guerrilla group run by a wealthy settler who is recruiting large numbers of disaffected young people like Yehuda. “I no longer have much use for my family, for the extended family which is called the religious Zionist community, “Yehuda told me. “Nothing like that matters anymore because everyone lied to me. No one had the courage to do what God commands. They [the rabbis and the leaders of the religious Zionist community] are all mityamrim [posers] full of more hot air than lofty ideals.”

In January, Ariel Sharon was hit with a massive stroke, and his Kadima Party—founded after right-wing members of the Likud Party rebelled over the Gaza withdrawal—was left in the hands of interim Prime Minister Ehud Olmert. Polls in January predicted that Kadima would sweep the March 28 election and that, in general, Israelis support negotiating with the Palestinians and rolling back Jewish settlements. But Israeli opinion surveyed before the Hamas victory in the Palestinian election may mean little today. Hamas has extended olive branches, but it clings to its core mandates of destroying Israel and establishing an Islamic theocracy over these troubled lands. Questions remain about how Olmert will respond, but he will most likely continue evacuating a good number of the 102 Jewish encampments located on the Palestinian side of the 700-kilometre security wall that Israel is still erecting and, in so doing, he may possibly spill the blood of religious Jews, young and old.

Essentially, religious Zionists believe that redemption will come only when Israel reclaims all of its biblical lands, a great arc stretching from Beirut to Baghdad. Only then will the Mes-siah arrive, will the dead return, and will the world finally accept the primacy of Halachic (Jewish) law. The Gaza pullout represented a renunciation of this Zionist dream, which still fires the imagination and which was one of the chief motivations behind the very creation of the Jewish state. But the religious Zionist community has reached a historic tipping point, and it appears that the forces of secularism, not religious idealism, will shape the future of Israel and its relationship with Palestine. “Israel in an ideological project,” said Elyakim Haetzni, a lawyer and a founder of the settlement movement, who vows not to move from his home in Kiryat Arba, a whitewashed town of 6,500 people in the occupied territories. “To undermine Zionism is to challenge the viability of the nation as a whole. This is what happened in Gaza. We are now living in the aftermath of a tsunami from which it is not clear we will ever recover.”

For Haetzni, as for Yehuda, the sins of Gaza and of the father—of Ariel Sharon, once the great champion of settlements but now the devil traitor—will not be repeated here in the West Bank, where the symbolism runs deep and where the overwhelming majority of settlers are religious Zionists.

Between December 2003, when Sharon first announced his plan to evacuate the Jewish settlements in Gaza and northern Samaria, and August 2005, when the Israeli Defence Forces (idf) and police successfully implemented the disengagement, the religious Zionist leaders vacillated between brazen defiance, deep contempt, and pathetic victimization—between a world-class boxer and a phlegmatic limb-swinging drunk—but were nonetheless unified in their opposition. During this time, the movement managed to jack up tensions in Israel to a point where even a sober Supreme Court justice predicted civil war. Referred to by secular Israelis as kippot srugot (knitted skullcaps), religious Zionists engaged in continuous acts of civil disobedience, and hundreds of thousands of them joined together for several three-day-long protests against the planned evacuation. Throughout this period the movement’s more extreme leaders called on Israeli soldiers to disobey any orders having to do with the evacuation. In late July 2005, ten rabbis instigated a pulsa denura, or death curse, against Sharon. At a huge protest in Tel Aviv, some Zionist leaders took public oaths of allegiance to the Gaza settlers; others, led by former prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s brother-in-law, political activist Hagai Ben Artzi, pledged to leave the Gaza settlements only in a coffin.

And then the army kicked in, clearing out the region in less than a week and without real incident. At the end of the day the only thing to leave Gaza in a coffin was the religious Zionist movement itself. “Ariel Sharon broke the back of our camp,” said Shaul Goldstein, the mayor of Gush Etzion, a bloc of twenty-one communities in the occupied territories, and a senior member of yesha, the Council of Jewish Settlements in the West Bank and Gaza. “Our rabbis are now arguing with each other to the point of total boycotts of one another. Our public is in shock, our youth is lost and despairing.”

To understand just how ugly things have become, one need only glance at the daily squabbles listed in Nekuda, the settlers’ weekly news bulletin, or listen to the religious Zionist community’s radio station, Arutz Sheva. In early December, the Jerusalem Post ran a full-page article titled “Heading for a Political Fall “which argued that the future of religious Zionism as a political force looks grim. Not only are the National Religious Party (nrp) and the National Union (nu) in what seems like an unstoppable slump in the polls, the leaders are deadlocked in a manner that shows no sign of letting up. Zevulun Orlev, chairman of the nrp, is struggling to distance himself from the concept of Greater Israel, wanting instead to emphasize education, identity, and social welfare. But men like nu Chairman Benny Elon identify with the old Gush Emunim (bloc of the faithful) theology that views Greater Israel as an integral step toward final redemption. For these men and many of their followers the state of Israel is not just a means of protecting Jews, it is a vehicle for redemption.

To stem their decline the nu and nrp have entered into a tenuous merger, but both have had their power base hollowed out. Whatever support they get will come mostly by default, i.e., from voters who see no viable alternative. In fact, many religious Zionists, who constitute up to one-third of Israel’s population, are threatening not to vote at all. More critically, the movement’s foundation, long anchored in extra-parliamentary institutions like yesha, has virtually disappeared. yesha, Goldstein told me, hardly exists any longer, despite most Israeli newspapers continuing to refer to it as alive and kicking. Senior operators like Baruch Spiegel and Yechiel Leiter, who once ran the show from backstage, have vanished from the political arena.

Witnessing all this raises the question: what really happened to the religious Zionist movement during the disengagement Off the top, the answer is easy. In August 2005, Israel deployed overwhelming force, the resistance buckled, its leadership imploded. Yet even this much is unclear, if only because a single spray of bullets from one Uzi submachine gun—which many settlers own—might have stopped the pullout in its tracks. That no settler chose to draw his gun means that something other than overwhelming force was operating here. Why did the community not act more decisively, heroically, even martyr itself And when the campaign was over, why was it unable to regroup or tend to its many psychological wounds Why did a movement that seemed so bullheaded end up shattering into a thousand different pieces by the finish line And most importantly, what can we expect from the religious Zionist movement in the future should the government choose to evacuate further settlements in the West Bank

In search of answers, late last year I attended a conference called “After the Disengagement: Religious Zionism and the Israeli society. “The gathering was hosted by Bar Ilan University, whose campus stretches across seventy acres of prime real estate in Ramat Gan, a ten-minute drive from cosmopolitan and secular Tel Aviv. There is little that is either secular or cosmopolitan about Bar Ilan. One cannot help noticing just how many students and staff wear skullcaps and just how many of the buildings, halls, and even individual rooms carry plaques that identify donors as Orthodox Jews. But for a secular Israeli like me, there is more to the feeling of being out of place here than the immediate recognition that one does not belong to this community. This feeling has to do with the university’s recent history, a past that foreshadowed the disengagement battles, which mostly luck prevented from becoming a civil war and an international disaster.

On November 4, 1995, a third-year Bar Ilan law student, twenty-five-year-old Yigal Amir, travelled to Kikar Malchei Yisrael, a city square in Tel Aviv, where a peace rally was being staged. By late afternoon the media were predicting a massive turnout, a forecast that caught the attention of then-prime minister Yitzhak Rabin’s senior handlers. They were hesitant. On several occasions since Rabin signed the Oslo peace accords his life had been threatened. An effigy of the prime minister in an SS uniform was marched through the streets of Jerusalem just one month before. Nor had the international Jewish community sat on its hands. In July 1995, Canadian-born scholar and mathematician Rabbi Nachum Rabinovich published an article in the Jerusalem Post that compared Rabin’s government to the Judenrat (Jews who assisted the authorities) in Nazi-occupied Europe and described Rabin as a moser, a collaborator who delivers Jewish lives or lands into the hands of enemies. While Rabinovich did not demand din rodef—the duty to kill a Jew who imperils the life or property of another Jew—he strongly urged settlers in the occupied West Bank and Gaza to lace their lands with explosives to prevent the Israeli army from engaging in any sort of evacuation.

That evening, Rabin’s motorcade left Jerusalem, and by 8 p.m. the prime minister was on stage delivering what commentators later called the speech of a lifetime. At 9.25 p.m., Yigal Amir, armed with a nine-millimetre Beretta, eluded the heavy security and shot Rabin three times before being apprehended. Two of the hollow-point bullets entered Rabin’s spleen, severing major arteries and his spinal cord. Just before 11 p.m., the prime minister died on an operating room table at Ichilov Hospital, a few blocks east of what became Rabin Square.

In the months that followed, a mourning and weary nation managed to hold off Jewish zealots long enough to take a few small steps toward resolution of the conflict with the Palestinians. Shimon Peres, who replaced Rabin, withdrew Israeli troops from six Palestinian cities. To distance himself from the attendant conspiracy theories surrounding the assassination, Benjamin Netanyahu, who took power in 1996, promised to be “the prime minister of all the people.”

After Rabin’s murder, it was impossible to persuade a cab driver to take me anywhere near the Bar Ilan campus. Many students reported feeling uncomfortable wearing skullcaps in Tel Aviv. At the same time, Israel was reaping the benefits of the Oslo Accords, its streets crowded with official visitors from the European Union, the Far East, and even from the Arab world. Israeli businessmen circled the globe developing new markets, and the Arab boycott crumbled.

And then came the Shamgar Commission’s investigation into Rabin’s death, which, among other things, exonerated the board of Bar Ilan. Two years later, things had completely deteriorated. The peace process was stalled, the Oslo agreements were frozen, negotiations with Syria had not been renewed, and the Arab world suspended all contact. The gdp dropped precipitously and the country descended into a Fortress Israel mentality.

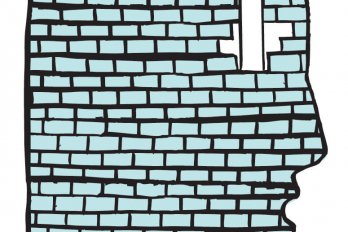

For the religious Zionist community, however, the discontentment of the late 1990s were halcyon days. Like clockwork, their trains kept running: 154,000 settlers moved to the West Bank, hundreds of vigilante attacks on neighbouring Palestinian villages were launched, and a tunnel excavated beneath the Wailing Wall came dangerously close to the Al-Aqsa mosque, one of Islam’s holiest sites. Countless other provocations—including, especially, Sharon’s walk to Jerusalem’s Al-Aqsa mosque—triggered a second, and far more violent, Palestinian intifada. In real terms, it was not until the disengagement campaign of August 2005 that these trains hit a brick wall and religious Zionism began leaking confidence in itself and its mandate.

How could the Israeli government have allowed such footloose behaviour Why did Peres not treat Rabin’s assassination as an occasion to censure the religious Zionist movement as the Egyptian government had censured the Muslim Brotherhood or, more significantly, as Israel has demanded the Palestinian Authority do to Hamas In this context, it must be repeated that the religious Zionist idea of Greater Israel calls not only for the annexation of all the occupied territories, but the conquest of the entire Beirut-to-Baghdad biblical homeland. It is, therefore, no less grand and fanciful than Hamas’s insistence that Israel be wiped off the map. Both are untenable fantasies that only create havoc in the minds of youthful aspirants and lead to the most extreme types of behaviour.

At the very least, one might have expected the government to force the closure of extremist seminaries, like those run by the disciples of the murdered Rabbi Meir Kahane, who advocated the expulsion of all Arabs from Israel, and the Bar Ilan Kolel, where Yigal Amir studied. But even in the few instances in which seminaries were closed, they quickly resurfaced having changed only their names. Any way one looks at this period, no decisive measures were taken, and through the hearts of religious Zionists bad blood continued to flow.

Some Israelis explain the passivity of the government by citing the exigencies of national unity. Others point specifically to the peace process, arguing that negotiations with the Palestinians could not proceed if Israeli society was openly divided. Idit Zartal and Akiva Eldar, the authors of Lords of the Land, claimed that the government was simply intimidated by the religious Zionist movement. Yigal Amir’s biographers, Michael Karpin and Ina Friedman, were blunter still, pointing out that to have acted decisively Israelis would have had to first “penetrate dark corners of religion and politics, basic Halachic issues, the relationship between religion and state.”

To Karpin and Friedman’s inventory of dark corners, I would add the concept of Zionism itself. Because Zionism is a commitment common to both religious and secular Jews, it is not something any politician tampers with easily. Both groups subscribe to the notion of Zionism as grounded in the right-of-return for all Jews. Secular Jews cleave to historical rights, religious Jews to entitlements derived from biblical scripture. As a result, there is a wholly fluid movement between religious and secular Zionism, so much so that it is impossible to change one without seriously altering the other.

Theoretically, it might be argued that Zionism achieved its principal goal with the founding of Israel in 1948 and that by now it has overstayed its welcome. Israelis could jettison the “rights “argument and replace it with a watered-down version of Zionism akin to the patriotism to which most nations subscribe. But a majority of Israelis hang on to a far more aggressive version of Zionism as one would hang on to a life raft and believe that to whittle off a plank, even one that is clearly rotten, is to put Israel itself at risk.

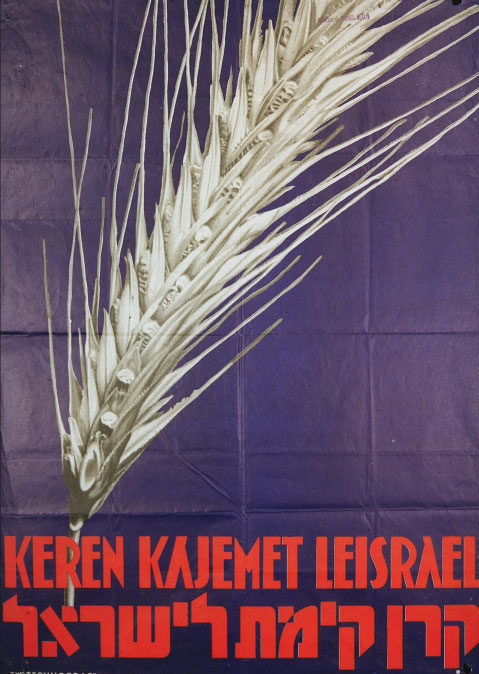

The religious Zionist movement has existed since the late 1890s, though it gained momentum only in the 1930s when Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook first articulated arguments that allowed religious Jews to embrace the Zionist project. Before Kook, most religious Jews held that there ought to be no state unless the Messiah declared it. Kook, on the other hand, argued that Zionism was not merely a political movement by secular Jews, but a tool of God to promote a divine scheme initiated by the return of the Jews to the promised land.

While a generous and a tolerant leader, Kook had a rather patronizing attitude toward secular Zionists. “They may think they do it for political, national, secular reasons,” he wrote, “[but] the actual reason for them coming to resettle in Israel is a religious Jewish spark [nitzotz] in their soul, planted by God.” But Kook did not overplay this hand. For the most part he respected the positions of secular Zionists and was a good friend of Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion. Kook established the largest yeshiva in the country and became the nascent state’s first chief rabbi. From Merkaz Harav, his seminary in Jerusalem, the venerable rabbi preached moderation, personal integrity, and individual choice. The single most important feature of Kook’s teaching may have been his notion that redemption’s foremost agent was the individual, not the state. This view allowed early graduates of Kook’s yeshiva to remain behind the scenes, to accept that God expresses his will through the individual, and that there was therefore no reason to seek power. In 1956, religious Zionists formed Mafdal, which grew to become the nrp, but they did not append to it a competitive national agenda. Rather, the nrp concerned itself with religious issues and defending the rights of religious Jews.

All this changed in 1967, when the agent of redemption suddenly became the state of Israel itself. “To us [religious Zionists] the Six Day War seemed like a miracle,” Yigal Amir’s mentor, Rabbi Raziel, told the media at the time. “The Egyptian air force destroyed in a few hours; the whole land of Israel ours in a few days. It was beyond anything natural, the hand of God in the process of redemption.” Within months of the war, religious Zionism, once a largely apolitical force, consolidated on the right and became more directly involved in matters of state.

Seven years later, in 1974, this same community formed Gush Emunim, the settlement movement from whose ranks arose men like Yonah Abrushmi, who threw a grenade into a crowd of Peace Now activists, and Yehudah Etzion, whose plan to blow up the Al-Aqsa mosque was foiled in 1984. Dr. Moshe Hellinger, a political science professor at Bar Ilan University who spoke at the conference I attended, argued that today being part of the right-wing coalition has become the sine qua non of the movement and that “there is [now] no dialogue between the huge majority of right-wingers and the tiny minority of left-wingers.” Insisting that “many religious Zionists know next to nothing about their history or ideology, or anything else but that they are committed right wingers,” the young professor was almost booed off the stage.

While striking, many attributed Israel’s victory in the Six Day War to something other than divine intervention. “We were all swept up into a major euphoria, “General Shlomo Gazit, who later led Israel’s military intelligence, told me when I visited him in his office at the University of Tel Aviv. “But over time most of us got over it. We realized that in large part our exhilaration could not really be explained by the fact that we were now in possession of those Jewish sites which our ancestors had always dreamed of. In fact, many of us were so secular that we didn’t give much of a damn about such things. What caused us to feel so intoxicated was that our military had done so much better than anyone had dared expect.”

Such confidence was almost shattered in the 1973 war with Egypt and Syria, a devastating conflict in which Israel had to rely heavily on American arms shipments. That war speaks volumes about the paranoia Israelis feel about security and the need to create buffer zones between themselves and their Arab neighbours. The assassination of Egyptian President Anwar Sadat after he signed a peace treaty with Israel made the point that moderates would not survive. And so an emboldened Sharon, then Israel’s defence minister, led the incursion into Lebanon. Two intifadas erupted, violence cycled upon violence, and, over time, most Israelis came to accept that the military’s top brass and Israeli politicians must work hand in glove to protect the state.

Today, no sober politician believes that the Israeli army is anything less than a well-oiled machine, fully capable of exploiting the weakness of Arab states and of the Palestinians. But few Israeli politicians or military strategists think in terms of an ultimate victory. Everyone prefers to talk about managing the conflict for decades to come, and few mainstream politicians or military officers consider the Islamic Jihad, Hezbollah, the Al-Aqsa Brigades, or Hamas as anything more than a serious pain. As idf Chief of Staff Dan Halutz recently put it, the terrorism of these groups is simply a “nuisance.”

By and large, however, religious Zionists have not adapted to the unfolding reality on the ground and continue to think of the conflict with the Palestinians and with the Arab world in mythological, timeless terms. They exist in a finite, temporal state, perhaps, but also in a place (and through a history) that is regarded as transcendent, and it is this belief that gives the movement broad appeal. Throughout the Gaza disengagement, the leadership of the religious Zionist movement cast Arabs in general and Palestinians in particular as the latest incarnations of Amalek, the arch-enemy of Biblical Hebrews. They marched holding placards displaying photos of the Lubovitcher rabbi, Menachem Shneerson, with captions written in Biblical language that read, “Gentiles must leave the land of Israel, so that they shall live. “In the rhetoric of the rabbis and right-wing leaders prior to the disengagement, Jews were consistently depicted as “the chosen people “and the “light unto nations “or they were spoken of as Holocaust victims who must now rise and avenge themselves.

At the enormous protest in Kfar Maimon preceding the Gaza pullout, a rabbi claimed that the nations of the world would simply stop existing were it not for Israel. Made with a straight face, such statements smack of a dangerous nationalism and are, in a sense, laughable. Measured against the actual reality of life in the Middle East, the rabbis struck many secular Israelis (and certainly foreign journalists) as rubber figurines promoting a heightened sense of paranoia and condemning Israel to neta zar, an inimical or alien element. But with their rhetoric sounding from bullhorns, the rabbis soldiered on, and, upon reflection, I realized that it was not nationalism to which they were speaking, but rather it was the dream of redemption.

What is fascinating about the more extreme rabbis is just how incapable they are of curbing their impulse to wax on about security issues, even though very few of them have taken the trouble to educate themselves on such matters. When I interviewed Dov Lior, the chief rabbi of Kiryat Arba, it was clear that he was a military junkie. After he laid out a particularly grim assessment of the Palestinian Authority, I asked Rabbi Lior if he considered himself an expert on Arab terror. He responded that he knew next to nothing about such things but, not two minutes later, he was again dishing out advice on security matters. Rabbi Lior seemed unable to control himself not because he lacked personal discipline, but because for him the concept of redemption is inextricably welded to national politics, and he is unable to distinguish between the two.

When Rabbi Lior spoke directly about geula (redemption) his eyes lit up, communicating a sense of excitement that was palpable and intoxicating. He seemed to feel that we would all be better off if we could only believe that the simple, physical act of settling Israel is the expression of a preternatural process that will end with the rising of the dead and peace on earth. If one could only let this idea serve as the marrow from which meaning flowed, then the problem of leading a meaningful life would be solved. The symbols and mythic elements that constitute the language of redemption—through which religious Zionists extend ancient mythology into the present—prop up such a belief. And without the seminal idea of Greater Israel, it is doubtful that Zionism itself would have the mass appeal that it does. The pillar of fire may not have arrived, but the pillar of Israel is Greater Israel itself.

Ariel Sharon realized that religious Zionism is timeless and immutable, that it might bend but that it will never break. As such, the Gaza pullout was a gamble. When settlers accused their former champion of being a “turncoat,”of “exiling Jews under fire, “Sharon replied that “things had changed.” The religious Zionist leadership responded that things had not changed, and that they never will. But of course Sharon’s gambit ultimately worked, and the movement has suffered a mighty body blow.

At the Bar Ilan conference, Nissan Slomiansky, an nrp member of the Knesset, spoke about the three pillars of religious Zionism—Eretz Yisrael, Torat Yisrael, and Am Yisrael; the land, the holy books, and the people of Israel. Claiming that they are all woven together and must be respected and advanced by every generation of Jews, and taking direct aim at Sharon, he continued: “The nails which hold these three elements together are hammered in just so, and to lose one element is to lose them all—have the edifice in its entirety dissolve. This is just what Arik wanted and did. During the disengagement, the prime minister raped us. He forced us to choose between the three things we loved equally. It was a black day, but we finally chose Am Yisrael, the nation, which is why there was no undue violence during the disengagement. But we must also admit to ourselves that the battle over Eretz Yisrael, the land of Israel, was lost in August of 2005.”

While damaged, religious Zionism is not without answers, not without agendas. As Slomiansky put it, “We expected that hundreds of thousands of Israelis would come down the Gaza settlements and embrace the settlers. But not more than a trickle made their way down to the settlements to support us. Why Because we religious Zionists had not embraced the people of Israel properly in the first place. We must take a deep look at ourselves, think about new ways of embracing the nation more firmly, more unshakably, more lovingly. We must win over the hearts and the minds of the people.”

Slomiansky’s mea culpa resonates strongly among the kipot srugot, including the mayor of Gush Etzion, Shaul Goldstein. He is a short, squarely built man with blue eyes set in a boyish face. In a former life, he was a contractor who did well for himself by developing land in the West Bank. Born into a secular family in Jerusalem, he built his own home in the settlement town of Efrat and now presides over the oldest settlement bloc in the West Bank. Goldstein has received considerable notoriety by declaring his position on the Security Wall. “No one wants it, “he told me even before I asked. “The International Court at the Hague has declared it illegal. The Americans, the Europeans, the Palestinians all want construction to stop. So why is it still going up “But Goldstein’s opposition to the wall comes from a different set of concerns than those expressed by the international community. Whereas the UN and EU worry about entrapping Palestinians, Goldstein is anxious about the Jewish settlements that may find themselves on the wrong side of the wall.

This much notwithstanding, the Israeli media has had a field day with the issue: “Anarchists Against the Wall recently received a new recruit,” one newspaper article began. Goldstein was not amused, but took the opportunity to put forward his own view of the disengagement defeat, which he happily repeated for my benefit. “After the disengagement, a large segment of our public suddenly realized that the flag we had waved all these years hadn’t forged a connection with anyone. We were the vanguard, leading a non-existent camp. We ran alone, we charged ahead, and when we looked back, we saw that there were no armies, that they simply weren’t there. So I proposed to my friends in yesha that we announce that there is no longer a yesha Council, that in its place is another council, one that can embrace other values…that in order to hold on to Tekoa and Karmel Tsur [two isolated encampments in Judea] we need to build outposts in Tel Aviv, Beer Sheva, and Afula.”

Besides the Slomiansky/Goldstein approach, there are at least three other reactions to the Gaza defeat worth mentioning. Moderate religious Zionists are prepared to let bygones be bygones, arguing that the disengagement is a fait accompli. “No amount of tears will bring back our beloved settlements,” one rabbi told me. “We can only hope and pray that God will not allow another such campaign. And by the way, it does not hurt one bit that Sharon is pretty well finished.”

Others, led by Rabbi Uri Sharky, a senior member of Machon Meir (a right-wing think tank) and a rising force among religious Zionists, take a far more aggressive approach. In addition to direct action against any future evacuations, Sharky wants to infuse Israeli society with the spirit of religious Zionism by making the Supreme Court subservient to the Rabbinical Court, requiring religious education in schools, and creating sophisticated religious media outlets for propaganda purposes.

Then there are religious Zionists who want nothing more to do with the state of Israel, but who will pursue their dreams at all costs. This group includes many young people who insist that they will not serve in the armed forces, will not vote, and will no longer pray for the state or for the army. This group includes young men like Yehuda, who no longer think of themselves as mere Zionists but rather as “saviours” of the Jews and of Judaism itself.

There are echoes of the same determination (and anger) in Elyakim Haetz-ni. When I visited him at his home in Kiryat Arba, Haetzni told me that he would much rather give up his Israeli citizenship and live under Palestinian rule than move out of his home. During the run-up to the disengagement, Haetzni recommended that resistance take the form of illegal roadblocks and sit-down strikes. Like most members of yesha he did not suggest military disobedience, and most certainly did not endorse firing on Israeli soldiers. “But there are a hundred shades of grey between the passivity that finally characterized the resistance and the shrill insanity that some of the rabbis had called for.”

Haetzni’s big idea was to fill the jails with protesters. This tactic, he believed, would have forced the government to reconsider. And for the first few weeks of the resistance, it seemed that his plan might have worked. In May and June 2005, at intersections across central Israel and on the ramps to major highways, hundreds of young protesters wrapped themselves in orange T-shirts, orange ribbons, and orange headgear, and carried enormous signs with slogans like “Sharon is bending to terror” or “A Jew does not exile a Jew.” But one of Israel’s most popular broadcasters announced on public television that the next time he ran into protesters he would beat the living daylights out of as many of them as he possibly could. The broadcaster was not alone, and such animosity caught yesha off guard. Fearing a total shipwreck, the leadership redeployed its troops to legal protests in Kfar Maimon and Tel Aviv’s Rabin Square.

“They [yesha] simply have no balls,” Haetzni told me. “What did they think That acts of civil disobedience would make the people love them Of course they would not. The point of the disruptions was not love but imprisonment. By backing off this strategy, the rabbis proved that they simply do not have what it takes to lead. They want to be loved not only by family, friends, students, but by the nation as a whole. Most of them really believe they are acting in the nation’s best interests and cannot get it into their thick heads that not everyone sees things as they do.”

Haetzni’s disdain runs deeper than he would like to admit. As a Holocaust survivor who moved to Tel Aviv soon after World War II, Haetzni does not countenance any kind of passivity. On September 5, 1972, the very day eleven Israeli athletes were kidnapped and then killed at the Munich Olympics, Haetzni packed up his young family and moved from bustling Tel Aviv to the Judean Hills. “Moving to Kiryat Arba was all about my rights as a Jew. The kingdom of Jordan prohibits any land sale to Jews. And Kiryat Arba, to which I moved, operated under Jordanian law. I needed to take a stand against such things.”

It is with this history in mind that Haetzni views the lack of resistance to the Gaza pullout as an abomination never to be repeated. For him it is simply a matter of human rights, the right that any man or woman has to live wherever they so choose. “Arik Sharon, as the democratically elected prime minister of Israel, had the right to withdraw Israeli troops from wherever he likes. The prime minister can even go so far as to turn off the lights that Israel has supplied, reroute the water mains, the roads leading in and out of the Gaza settlements. But what Sharon had no right to do is force settlers to leave their homes. He had no right to render Gaza Judenrein [free of Jews]. Those who wished to remain under Palestinian rule should have been allowed to do so. And if it were me living in Gaza, I would have preferred to stay put rather than give up on my Zionism and on my right to live wherever I so wish.”

In one sense, Haetzni was simply letting me know that should Israel wish to evacuate the Hebron region in which he lives, he will not move and may fight to the death to preserve his fundamental right. But it is interesting to note the extent to which Haetzni’s core beliefs converge with the more extreme elements within Israel’s left wing. Might his commitment to a rights-based religious Zionism extend to Palestinians wishing to live in Israel Do they not also have the right to live wherever they wish Are they not equally entitled to the right of return If the answer to these questions is “yes, “how will the Jewish state remain a Jewish state Perhaps, in the end, there is an internal contradiction in Zionism—a contradiction that is irresolvable. I asked Haetzni if it was not paradoxical that his extreme rights-based position blended with those advocating a binational state.

He smiled and said, “After all, this is the Middle East.”