The jagged Sawtooth Mountains loomed in the distance as the elders sauntered into the faux-stone band office in Telegraph Creek. Taking off their shoes, they asked to see Chief P. Jerry Asp. A receptionist led them upstairs to the crescent-shaped conference room, where band manager Bob Edzerza told them that the chief was meeting with Shell Canada in Calgary. He asked if he could help.

“We’re here to meet the chief,” elder Terri Brown replied. “And we’re going to stay here until he returns.”

Edzerza sat quietly for a moment, as if struggling to comprehend. It was mid-January, and the pink glimmer of a winter sunrise crept slowly across the room. He excused himself. The elders exchanged nervous glances across the oversized conference table. Most were grandparents, some had great-grandchildren in the village; few had ever done anything like this. When he returned, Edzerza said the chief would be back on Wednesday, and offered to set up a meeting.

“We’ll wait,” Brown replied.

They waited for eight-and-a-half months.

By the time the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada took over operation of the northern British Columbia band office in late September, this quiet gang of elders—most in their sixties and seventies—had inspired a blockade, an industrial strike, and the arrests of fifteen Tahltan. And as 2006 dawns, they may pose an obstacle to Premier Gordon Campbell’s plans to reopen British Columbia to large-scale mining, as well as his hopes for a “new relationship” with First Nations.

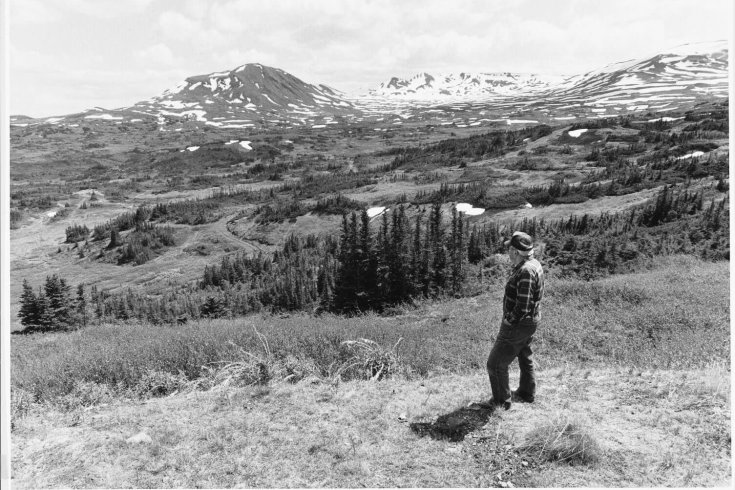

The Tahltan are a loosely knit band of matrilineal families who share Athapaskan roots and a claim to roughly 150,000 square kilometres of the most resource-rich terrain in Canada. Their vast inland territory stretches from the northern Canadian Rockies to the Alaskan border and contains the headwaters of some of Canada’s wildest rivers, including the Nass, Skeena, Dease, Iskut, and Stikine. It’s a place so large that, in the words of explorer and ethnobotanist Wade Davis, “Canada could hide England [there], and the English would never find it.”

The Tahltan are relentless hunters, and though a few families practised their traditional nomadic lifestyle as late as the 1950s, most now live in three small communities. Telegraph Creek, the only town on the 600-kilometre Stikine River, is home to the largest reserve. Iskut, nestled in a mountain pass near the fabled Spatsizi Plateau, is home to the descendants of several inland families. And Dease Lake, a muddy strip hunkered along Highway 37, hosts the newest reserve and the only concentration of businesses in the territory.

It was in Dease Lake that NovaGold Resources decided to host a community assembly in January 2005. NovaGold controls one of the largest undeveloped mineral deposits in North America, at Galore Creek, where an estimated 13 million ounces of gold, 156 million ounces of silver, and 12 billion pounds of copper lie buried. But Galore Creek flows through territory claimed by both the Tahltan and the Crown. Before the Vancouver-based NovaGold can mine its claim, the province is required by law to “consult” and “accommodate” the Tahltan. This meant negotiating with the Tahltan Central Council (tcc), a nonprofit society that regards itself as the government-in-waiting for a Tahltan Nation.

As a prelude to provincial consultation, NovaGold worked with the tcc to organize a meeting on January 8 and 9. The company invested a reported $100,000 in the assembly, much of which went toward airfare and chartered buses to bring Tahltan home from as far away as Ottawa. One of the presentations at the meeting described a “memorandum of understanding,” signed two months earlier, under which the province was to pay the tcc $250,000 to negotiate agreements for future mining, forestry, and hydro projects. In addition to the NovaGold mine, four other megaprojects were in the works: bcMetals’ Red Chris gold and silver mine, Fortune Minerals’ Mount Klappan open-pit coal mine, Shell Canada’s Klappan Valley coal-bed methane project, and Coast Mountain Power’s Forest Kerr hydroelectric dam.

The audience was startled. Few were aware that so many large developments were underway. Many were disturbed to learn that the tcc, which was created to negotiate on their behalf with industry and government, was to receive funding from those with whom it was supposed to be bargaining. The elders took notice when Telegraph Creek chief Jerry Asp and Iskut chief Louis Louie returned from a private lunch with the NovaGold executives. Said Terri Brown, “It was very, very embarrassing for me as a Tahltan to see our leadership sit there like trained dogs.”

The Telegraph Creek elders returned home that weekend via one of the more spectacular two-hour drives in Canada. The route traces an ancient Tahltan path that was pummelled into a mule road during the Cassiar and Klondike gold rushes, then widened to a truck road during construction of the Alaska Highway.

Overlooking the scrubby boreal forest on the outskirts of Dease Lake is Mount Edziza, a 2,787-metre-high volcano that the Tahltan’s ancestors had routinely scaled to collect obsidian. They would chip the hardened black glass into knife blades and arrowheads for trade to neighbouring bands. As miners themselves, the elders had no cultural objection to a well-run dig. Some had worked at the long-shuttered Golden Bear mine, and many of their children held jobs at Barrick Gold’s soon-to-be-closed Eskay Creek mine. They were hoping the Galore Creek mine would replace the Tahltan-held jobs that would be lost because of the Eskay Creek closure. But five projects? That would create far more jobs than the few hundred working-age Tahltan in the region could fill, prompting an invasion of fortune-seeking labourers, whose presence would further complicate the already thorny issues of land claims and self-government.

Halfway to Telegraph Creek, the gravel road begins to parallel the Grand Canyon of the Stikine. In this 100-kilometre-long gorge, the river has carved a window into the past. The rocks on the river bottom were thrust into place by continental plates more than 180 million years ago, and the walls soaring hundreds of metres above the river are the stratified remains of a 90-million-year-old lake bed. This prehistoric layer cake has been preserved for the past five million years by a cap of hard rock formed when volcanoes rerouted the river. Below it all, the Stikine churns so violently that only a handful of expert kayakers have managed to paddle its length. BC Hydro wanted to build two seventy-storey dams here in the 1970s. The project would have flooded the canyon and much of the surrounding territory. The Tahltan opposed the dams—one elder publicly threatened to blow it up—and under the leadership of Tahltan chief Ivan Quock the plan was defeated.

Just downriver from the canyon, the clear blue Tahltan River swirls into the muddy Stikine. The Tahltan have been harvesting salmon along these banks since the last ice age ended thousands of years ago. The northern shore is speckled with fish-drying sheds and brightly painted summer cabins. A cliff soars to the south, rippled into two forty-metre arcs—a supernatural sculpture that evokes a massive eagle. This is the heart of Tahltan country.

Twenty kilometres west, the road crosses a one-lane bridge and winds into the first of two Telegraph Creeks. “Downtown” Telegraph Creek is a graveyard of broken dreams. Victorian frame houses sag inward, while lopsided log homes tilt out. Vintage pickup trucks and dogsleds lie abandoned among the cottonwoods. Telegraph Creek took its name from an audacious plan to build a telegraph line from New York to Paris via Siberia. The project was abandoned after the transatlantic cable was laid first. The river town blossomed briefly as a supply depot for the Klondike gold rush and again during the construction of the Alaska Highway. But for most of its long history, downtown Telegraph Creek has survived on a slow trickle of hunters (and, later, hippies) calling in at the inn that occupies the old Hudson’s Bay Company post.

“Uptown” Telegraph Creek is reminiscent of a Toronto suburb. Above the main drag sit several dozen split-level homes, their lower floors half-buried in Mississauga-sized yards, their upper floors sheathed in pastel shades of white, yellow, and baby-blue vinyl siding. A health centre and Catholic church flank the north side of the road below, while a community centre, general store, and fire hall line the south side. The two-storey band office stands at the far end. Inside, at the top of its broad, curved stairway, hangs a framed copy of the Declaration of the Tahltan Tribe, signed on October 18, 1910, by Chief Nannock and eighty-two other Tahltan. It reads: “We claim sovereign right to all the country of our tribe—this country of ours which we have held intact from the encroachments of other tribes, from time immemorial, at the cost of our own blood.”

Uptown was abuzz the week after the NovaGold assembly. A series of impromptu gripe sessions at the store led to an evening of tea and strategy at Pat Carlick’s house, which paved the way for a meeting of the Tahltan Elders Society. On Sunday night, January 16, Terri and Lucy Brown approached several elders and asked if they would support a sit-in. All said yes. “I thought they wouldn’t keep the secret,” said Terri Brown, whose experience as an activist (she’d been president of the Native Women’s Association of Canada and the National Action Committee on the Status of Women) thrust her into an organizing role. “The office would be locked up and that would be it.”

But by sun-up the next morning, the elders were seated in the conference room. News of the sit-in spread quickly, and more elders arrived by the truckload. By suppertime, between forty and fifty people were jammed into the room, laughing and telling stories.

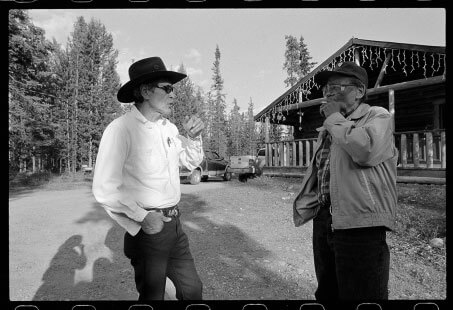

August Brown, a former ranch hand who still dresses like a cowboy, shared a tale about Chief Asp. They’d grown up together in Lower Post, a small town just south of the Yukon border. The future chief, he told the elders, used to shoot pine cones at the other boys with a slingshot. Brown reminded Asp about this shortly after he was elected. “I got a piece of pine cone,” he said. “I put it right in front of him, on his desk.” August paused to mimic Asp’s puzzled expression. “Finally he smiled. He picked it up. He looked at me. I said, ‘You remember that?’”

About a dozen elders slept in the band office that night, nodding off around the conference table as if it were a campfire. In the morning, they talked about what to do about Chief Asp. Though Asp is Tahltan and an elder (he has seven grandchildren), he does not live in Telegraph Creek and had never been part of the community. After growing up in Lower Post, he had dropped out of high school to work as a miner, taking on a variety of jobs in British Columbia and the Yukon before founding Tahltan Nation Development Corporation, a construction and camp-services company that is now the largest employer in Dease Lake. As founding president of tndc and vice-president of the Canadian Aboriginal Minerals Association, Asp was one of British Columbia’s highest-profile native businessmen. He lives in a modest off-reserve home in Dease Lake.

Asp was elected chief of the Tahltan band in 2002 and again in 2004, promising to lure investment and lower unemployment. (He succeeded: the Tahltan enjoy a 6-percent unemployment rate, one of the lowest among First Nations.) His campaign strategy had focused outside the community, though, relying on the Supreme Court of Canada’s decision in the case of John Corbiere et al. v. Her Majesty the Queen and the Batchewana Indian Band. In accordance with the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the Corbiere decision required bands to allow all their members to vote in Indian Act elections—not just those who live on a reserve, as had previously been the practice.

There are an estimated 5,000 Tahltan living in Canada, but fewer than a thousand live on the Telegraph Creek and Dease Lake reserves. (Iskut elects its own chief.) Asp mailed flyers to off-reserve Tahltan, and by all accounts was the first Tahltan chief to win election without receiving much—if any—support in Telegraph Creek. “About 90 percent of my support comes from off-reserve,” Asp said in an interview. “The on-reserve people don’t [have] control anymore and they don’t like it.”

The elders showed Asp just how much they didn’t like it on Wednesday morning. Asp arrived at about 11. The snow-covered parking lot was overflowing with pickups; the lobby was a sea of shoes. Some sixty elders confronted Asp in the entryway to the band office, beneath dozens of 8 x 10-inch colour photographs of local kids posed giddily in graduation caps and gowns. Elder Bobby Quock read from a prepared statement, accusing Asp of overstepping his authority, alleging a conflict of interest between his roles as chief and president of tndc, and demanding his resignation. “Jerry Asp,” Quock said in a grave, raspy voice. “You are no longer chief of the Tahltan people.”

Asp did not resign. Nor did he return to the band office after that day. And despite various efforts to oust them, the elders did not leave. The sit-in entrenched itself, the months wore on, and life at the band office settled into a rhythm.

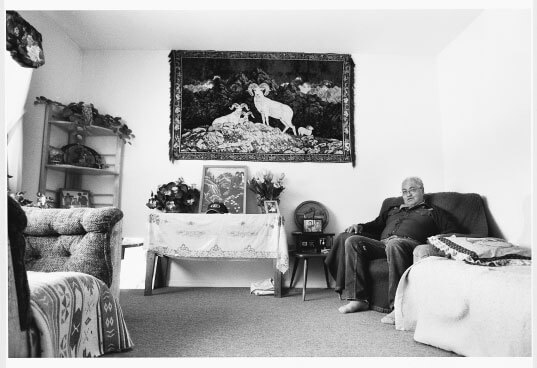

Lillian Moyer was usually the first one up in the morning, padding down the blue-green carpet in her slippers. Moyer grew up in Telegraph Creek, but developed tuberculosis when she was thirteen and was sent away to a Vancouver hospital. Though thrice married, she has spent most of her adult life as a single parent, working as a barmaid to support her children. She moved to Dease Lake in 1979, and eventually became a band councillor and head of the Tahltan Elders Society. Feisty and quick-witted, the sixty-six-year-old grandmother is known by both her friends and enemies as “Tiger Lil.”

Lucy Brown was Moyer’s most loyal companion. The two of them slept in the band office every night for the first four-and-a-half months. Brown has spent her entire life in Telegraph Creek. She and her husband, Orville, own one of the cookie-cutter houses that give the reserve its eerily suburban character, but spend much of the year in the nearby fishing or hunting camps. Brown is as quiet as Moyer is chatty, often reacting to her friend’s rants with a deadpan shrug, as if in a Laurel and Hardy routine.

Both women described the sit-in as something akin to a teach-in. Moyer was among the first generation of Tahltan to return to Telegraph Creek after living among mainstream Canadians. From her, Brown learned to expect more from government and gleaned a sense of activism. From Brown, Moyer relearned how to live as a Tahltan. For example, when Moyer harangued Brown about the time she was spending at her fish-drying camp, Brown responded with seven words: “Band office won’t feed us in winter.”

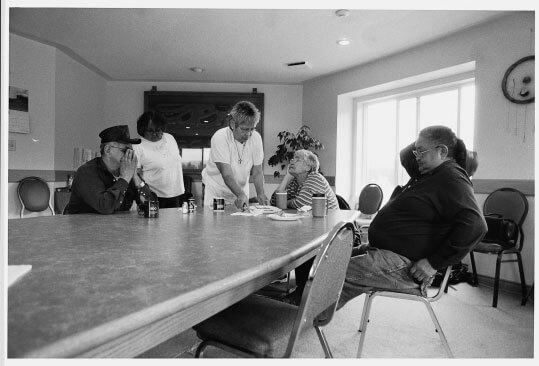

After the men dressed and put away their bedrolls, Brown and Moyer would serve coffee and eggs in the conference room. Another elder, Earl Jackson would roll up to the office each morning by 8:45, and the night watchmen—younger Tahltan backing the group—would leave for the day. In an unusual bit of protest symbiosis, the office workers would arrive. Though the staff had been sent home the first few weeks, the elders went out of their way to invite them to return. Support for the sit-in would dry up quickly if local assistance cheques stopped flowing to the rest of the community, so the elders confined their activities to the upstairs kitchen and the boardroom.

With Jackson on duty, Moyer was free to stroll around the village for an hour or two. Her rambles were part exercise, part civic politics. With no local newspaper or radio station serving Telegraph Creek, chit-chat is how news travels. In the evenings, the crowd would swell to two or three dozen as neighbours dropped in with platters of salmon and moose meat. Pat and Edith Carlick were regulars; Pat speaks more Tahltan than most, and he challenged his fellow elders to keep their language alive.

After dinner, there were meetings. During the early months, the elders discussed immediate problems, such as the occasional calls put in to the rcmp to remove them (the police visited, but considered it an internal matter). Later, their talk turned to what a new Tahltan government should look like. At no point did they ever take a vote. Instead, they would talk until a consensus emerged. “I didn’t get it for the longest time,” said Terri Brown. “The guys were sitting around and not saying things, and the women were talking and being more in the forefront. I thought these guys didn’t support us. And what it was really about, was they didn’t say anything, so that meant they were supportive.”

The elders decided on a “one mine at a time” strategy, under which they sought to keep their children fully employed by selecting one megaproject per generation. In February the group enacted a moratorium on development until Chief Asp was out and a new Tahltan Central Council was in place. Entitled Dena Nenn Sogga Neh ‘Ine (Keepers of the Land), the document declared: “All agreements negotiated with industry and government to date . . . are hereby declared void.”

Inspired by the Telegraph elders, the Iskut band began a protest of its own in March. Iskut is the gateway to the Spatsizi and Klappan highlands, where Tahltan have traditionally hunted groundhog, beaver, moose, caribou, mountain goat, stone sheep, and bear.

The Klappan is also rich with coal. Fortune Minerals hopes to wrest 3 million tons of anthracite per year from the region by building open-pit mines, while Shell Canada plans to extract coal-bed methane for use as household gas. The methane-extraction process could involve drilling hundreds of wells through which gas can be forced to the surface. Each well typically requires a gravel pad about the size of an ice rink and each pad requires a connecting road. Iskut elders were concerned that Fortune would decimate Klappan Mountain and feared that the Shell project would transform the alpine valley into a gravel checkerboard, possibly polluting the region’s pristine rivers in the process.

Shell planned to discuss these concerns at assemblies in Telegraph Creek, Iskut, and Dease Lake in early March. When the reps arrived in Iskut, villagers were waiting in the snow in front of the band office. The children carried neon-green placards bearing slogans such as “Save Klappan” and “No Shell.” The elders wore traditional Tahltan regalia—red blankets decorated with black trim and white buttons—and sang Tahltan songs.

Standing behind the Iskut elders were several of their Telegraph Creek counterparts. The solidarity was remarkable, given the half-century of tension between the two villages. Around 1950, as part of an effort to corral natives onto reservations, many of the Iskut elders had been cajoled into wintering directly across the river from Telegraph Creek. They spent a decade on the so-called Stikine Nomad Reserve—a shoddy camp where both whites and more established Tahltan living in Telegraph Creek looked down on them—before relocating to Iskut in 1962. The mutual support passing between the two protests was for some a long-overdue détente.

When the men and women representing Shell stepped out of their muddy white suvs and saw the Tahltan, they smiled and waved, assuming they were being welcomed. It was not until they walked closer and read the placards that their faces fell.

The Tahltan scrummed around them. Iskut resident Oscar Dennis read a letter warning Shell that because the company had not talked to the Iskut elders before staking its claim, it had not fulfilled its duty to consult. Oscar’s father, James, spoke next. “We are looking after our own country,” the elder Dennis began. He started a second sentence, then stopped. Face to face with Shell’s Doug Ford, he became emotional. But like many natives of his generation, he had developed the habit of keeping his feelings well hidden in the presence of outsiders. Collecting himself, he looked Ford in the eye and said bluntly, “Go home.”

Iskut chief Louis Louie spoke last. Though he’d initially supported the developments, he’d since taken an earful from local elders and wasn’t about to openly defy them. “There will be no business on Tahltan lands,” he said, “due to the moratorium that was imposed by our hereditary elders council.” Impeccably inscrutable, Louie added, “We’d be very pleased if you’d just leave us alone.” Shell’s Doug Ford nodded gravely. “Thank you,” he said, as respectfully as possible. “Thank you very much.” The Shell delegation walked away quietly, their boots shuffling through the slushy snow.

The crowd adjourned to the school auditorium and gathered in a large circle. Chief Louie’s wife, Rita, prayed, throwing in a polite request that the Shell representatives have a safe trip home. The following day, the Iskut band council joined with the Telegraph Creek elders in withdrawing its support from the Tahltan Central Council.

In April, more than three months after the faceoff in the band office, Chief Asp finally met with the two groups of elders. The three-day meeting took place at the high-school gym in Dease Lake. Asp sat alone in the mouth of a large horseshoe of tables and chairs. Among the first to take the microphone was Pat Carlick. Pointedly speaking in Tahltan, he urged the present generation of leaders to think about future generations. But it was quickly apparent that few, if any, of those leaders could understand their native language.

The meeting’s facilitators asked that Tahltan speakers translate their statements. Carlick replied in English that at meetings like the NovaGold assembly, no one had bothered to translate technical language into something the traditional elders could understand. The crowd applauded.

Elder Millie Pauls rose next. “You know the language barrier we just had a few moments ago?” she asked. “Well, that’s the kind of dispute we’re having today.” She said the dispute was about more than just one chief and warned that a slate of megaprojects would overwhelm small communities. “All the old things will fade away,” she said. “What will be left for the children?”

Financial concerns arose too. NovaGold expects to unearth $6 billion worth of gold at Galore Creek, and billions more in silver and copper. The elders wanted more than a few hundred jobs—they wanted better schools and money to improve their communities. “Our country is going to be torn up and the Tahltan people don’t get a penny out of it,” said Bobby Quock. “We should get shares or a percentage.”

The months of debate that had taken place in the band office were evident as the elders—many of whom had only grade-school educations—spoke knowingly about arsenic released by gold mines and waste-water problems associated with coal-bed methane production.

Chief Asp had a chance to respond in the afternoon. He walked up to the microphone and spoke with his hands behind his back, his eyes fixed on the ceiling. He acknowledged the animosity in the room, then reviewed each of the development projects. “NovaGold has set a standard that every mining company in our traditional territory must meet,” he said, before speaking about Shell, Fortune Minerals, and bcMetals. Though he had concerns, he stressed that the province was moving ahead with or without Tahltan support. The one-mine-per-generation idea, he said, was simply not an option.

Asp knew better than most how eager the provincial government was to re-establish British Columbia as a mining province. During Premier Gordon Campbell’s two victorious election campaigns, he had promised to reduce barriers for foresters and miners. To avoid consultation with First Nations for projects on contested land, his government fought aggressive court battles with the Taku River Tlingit and the Haida nation. After this tactic failed, they imposed “Forest and Range” agreements that paid First Nations as little as $500 per member in exchange for access to timber and other resources. But the BC Supreme Court struck those agreements down in May. Stymied, the premier recently launched a high-profile plan to develop a “new relationship” with First Nations.

A vicious question-and-answer period followed Asp’s response. A veteran aboriginal politico named Allen Edzerza stood behind Asp during the questions, occasionally whispering in the chief ‘s ear. It was Edzerza who, as a consultant to the tcc, had negotiated the memorandum of understanding that had provoked the elders in January. And it was Edzerza to whom Premier Campbell had turned to help craft his new start with First Nations—a reminder to everyone present that the province stood behind Asp’s agenda. “The only way you can get your concerns heard is to be part of the process,” the chief told the assembly. “We can say we are not going to the table, and government will say, ‘That’s fine.’ We have no choice—absolutely none whatsoever—but to be involved in mining.”

Sunday’s meeting started even more contentiously. After a squabble about who was, and was not, sufficiently Tahltan, most of the traditional elders walked out. In their absence, the tcc passed a resolution endorsing itself. A member of Asp’s family, Edward Asp, moved the motion, stating, “All elders attending a properly convened meeting of Tahltan elders resolve that the tcc is the sole and proper authority to address issues of Tahltan title, rights, and interests.” A second motion supported Jerry Asp’s status as chief of the Tahltan band.

The next day the tcc distributed a press release promoting the resolutions. It was a brazen move. It may have impressed the mining companies, but to the Telegraph elders and much of the Iskut band it was a declaration of war.

The glacier of discontent that had formed in January was a river by July. On the fifteenth, a heavy-equipment operator from Iskut named Peter Jakesta got a call from a company wanting to clear a campsite. As soon as he learned that the work was for Fortune Minerals, Jakesta knew he wouldn’t take the job. The next morning, he went to Ealue Lake Road, where he waited until an eighteen-wheeler arrived, laden with heavy equipment. As the truck approached, he and his then-three-year-old daughter, Katrina, stepped into its path.

The driver stopped and climbed down. Jakesta told him the road was closed. The driver asked why. “The people negotiating for this land do not represent us,” Jakesta replied. “We are blocking the road.” The driver went to call his boss, and Jakesta’s wife, Rhoda Quock, sped to Iskut to round up support. By the time the driver returned, there were a half-dozen Tahltan waiting. Oscar Dennis served the driver with a warning letter similar to the one he’d given Shell back in March. The driver left and the Tahltan set up camp by the side of the road.

For the first few days, a handful of elders came from Iskut to sit around the fire and tell stories. It was fishing season, and many Tahltan were loathe to leave their spots on the Stikine to join the protest. Then, a few days into the blockade, a semi carrying Alaskan salmon crashed just south of the roadside camp. Salmon spilled from the overturned trailer. The Tahltan retrieved hundreds of fish and built drying racks. For many, the salmon were a sign. The camp began to grow, and a few Telegraph Creek elders began commuting between the two protests.

Like the Telegraph Creek sit-in, the Iskut blockade evolved into an informal seminar led by a handful of strong women, in particular Rhoda Quock. “In Iskut everyone stays in their houses,” Quock observed. “Here they are getting to know each other all over again.” At night, with the sounds of the campfire crackling, the dogs sniffing about, and the wind rustling in the trees, the blockade had a timeless feel.

The sparks flying around the campfire soon spread to Chief Asp’s Tahltan Nation Development Corporation. On August 12, a group of heavy-equipment operators employed by tndc told a manager at the Eskay Creek mine that unless Asp resigned as president of tndc, they were yanking the keys out of their machines and starting a work stoppage. Barrick Gold depended on tndc to supply labour at the mine; more than a third of the 320 on-site workers are native. And tndc was even more dependent on Barrick; most of its 120 employees work at the remote mine. Neither company could afford a strike. By the following Monday, Jerry Asp had resigned from the company he’d helped found twenty years before.

After several postponements, Shell Canada and the tcc held a community meeting in August about the proposed development in the Klappan, but few elders attended—not even the lure of a free flight to Wyoming to tour US coal-bed methane fields could entice them to participate. Soon afterward, the company postponed its plans to drill more test wells, depriving tndc of a $4-million contract.

But Fortune Minerals would not abandon its plan to drill twenty-five holes in order to complete its environmental-assessment application. On July 19, Fortune president Robin Goad flew out from the company’s headquarters in London, Ontario, to try to work something out. When that failed, Fortune petitioned a Vancouver court for an injunction against the blockade. Given only two days’ notice, no Tahltan could attend, and Fortune was granted its order.

When the confrontation finally came, on September 16, the Iskut protestors held a traditional ceremony attended by roughly 100 supporters. These included representatives from the Haida, Gitksan, and Wet’suwet’en First Nations. The Haida had launched a blockade of their own in the spring, over logging rights, and had thanked the Telegraph Creek elders for the inspiration.

Wearing their button blankets and marching to the slow beat of skin drums, the Tahltan elders marched in unison toward the waiting rcmp. Some of the younger children cried as ten Tahltan elders and five youths were handcuffed. Among those arrested were James Dennis, who had faced off with Shell in March; Bertha Louie, a disgruntled director of the Tahltan Central Council; and Rita Louie, wife of Iskut chief Louis Louie. The honour of being the first elder hauled off to jail was reserved for “Tiger Lil” Moyer.

The Telegraph Creek band office stood empty over the fall. Indian and Northern Affairs Canada shut it down at the end of September. Asp said he requested the action because the band was behind on its housing payments; the elders believe Asp simply wanted them out. As a result of the takeover, Chief Asp and the band council lost all administrative authority. Autonomy will be restored after the next election in June 2006.

Lillian Moyer and the Tahltan Elders Society celebrated the takeover as a victory, predicting that future generations will remember the band office: “This is where the elders got their power back.”

Chief Asp disagreed. “How is it a victory for the Tahltan band?” he asked. He claimed that between the band office and the upcoming Eskay Creek layoffs, Tahltan unemployment will soar. “I’m still the chief and I’ll stay the chief until the next election,” Asp said. “I may run again just to spite them. And I’ll probably win . . . . Rest assured that the off-reserve people want me there as chief.”

Asp and the tcc maintained that the Tahltan should negotiate every proposal, because there is no way of knowing which will succeed and which will not, and because the province would proceed regardless. “They simply don’t understand. They think that every project will go ahead,” he said. “They aren’t doing anything constructive. Anybody can be destructive. Anybody. It doesn’t take a genius to be a critic. You just have to be an asshole with a big mouth.”

Terri Brown laughed at this assessment. “I think we can thank Jerry Asp,” she said. “In a way, he gave us a gift.” It didn’t matter to her whether or not she and the other elders had defeated the chief. “This success and victory thing, I don’t even know that it’s such a part of our vocabulary,” she said. “Success is not necessarily, ‘Did you shut the government down’ or ‘Did you shut the mining companies down.’ The success is what happened between [Lillian and Lucy] in the band office . . . . That’s where the real change is. When the individual changes, the nation cannot help but change.”