The most useful advice I’ve retained from my undergraduate program in creative writing is a lesson about structure from producer and screenwriter Peggy Thompson. She trained us to watch movies with a stopwatch, clocking the timing of different plot points, such as the call to action, the midpoint, and the climax—her rationale being that viewers’ commitment to mainstream films is tied to their expectations. If the plot twists don’t make sense or the story is taking too long to unfold, we’re more likely to walk out.

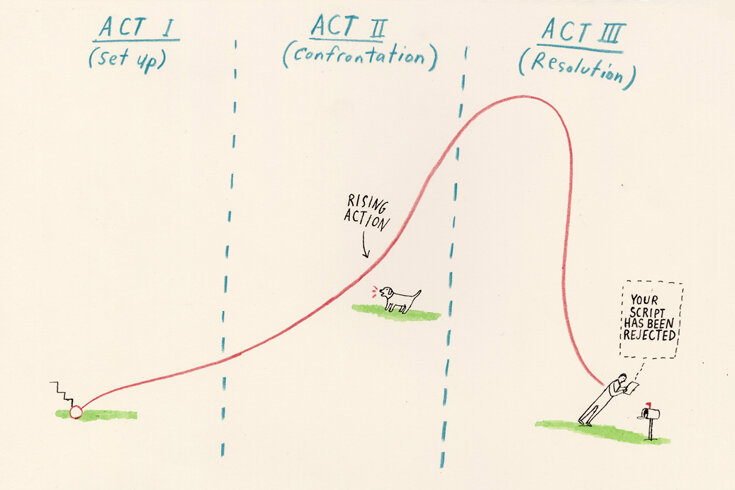

I called Thompson to discuss what struck me as similarities between the COVID-19 pandemic and the story-structure pitfalls she had taught us. The first part of the pandemic was rife with dramatic calls to action—the introduction of physical distancing, nightly cheers for health care workers. Then came progress in curbing infection rates, then (as in any epic struggle) setbacks. But, instead of resolving, as the plot of even the most basic Hollywood movie manages to do, things kept getting worse: ineffective lockdowns, quickly spreading variants, confusing vaccine rollouts. As many critics of the institutional response to the pandemic have observed, you could hardly tell the second act from the third, let alone a potential fourth—especially in regions that have been in and out of states of emergency for months. Now, more than a year since the pandemic started, we seem to have “lost the plot,” Thompson concurred.

Some psychologists say that the narratives we create around our experiences affect the way we feel about them; the same is true of narrative writ large. “On some level, we’re all little kids who look to narrative for answers,” said Thompson. “And we don’t have a lot of answers right now.” In this part of the world, trained as we are to expect a clear beginning, middle, and end, the same guidelines hold true for writing an epic like Star Wars and for responding to a pandemic. As an editor, I can tell you that, when fiction or nonfiction lacks an awareness of plot and structure, it leaves readers unsettled. Their attentions drift. Perhaps they start thinking about what to make for dinner. In the worst cases, the tension caused by a lack of structure can feel existential: Will the problem never be resolved? With increasing numbers of Canadians vaccinated, but the Delta variant quickly spreading, that’s a bit what the pandemic feels like right now.

Looking around at the faces of my colleagues on a recent Zoom call, I noticed that the adrenaline of covering the pandemic’s first wave had been replaced by a grim determination to get the job done: we are experiencing narrative fatigue. Some of us have been sick, and all of us miss loved ones. Yet not one person has given up on bringing in ambitious features, developing relationships with new writers, or working to get our stories in their best possible shape. That commitment reflects our love of the craft and of our readers. It’s also an act of protest against the moment we’re in. It helps us to know that this is a two-way street.

We were moved to learn that a doctor recently requested hundreds of copies of The Walrus for COVID-19 patients at half a dozen Toronto-area hospitals. Perhaps in life, unlike in art, the biggest victories don’t have tidy endings—but that doesn’t make our progress any less meaningful or compelling.