We are supposed to believe, if we think about it at all, that modern-day policing is unmoored from its historical past and its beginnings rooted in slavery. Yet examples of historical practices giving birth to current ones are everywhere. Take what in many police jurisdictions are often called street checks, or carding in Ontario, and stop-and-frisk in places like New York City. Carding is part of the long history of travel passes, which date directly back to plantation and urban slavery. Even in urban historical slave-holding centres like Montreal, Halifax, and Fort York (colonial Toronto), slaves and freed Blacks, in order to freely move around, required passes to prove their status to the white people who demanded them. More generally, slaves who ventured outside of their master’s homes or off their plantations could be required by any white man to prove, usually in the form of a note, that they had their master’s permission to move around. This practice, later modified, was codified in racially segregated places through pass laws and in the form of passbooks, which were documents that confirmed “legitimate” travel. But it also showed up in nations like South Africa, which segregated Black people into ethnic or tribal homelands, and in the way countries like the US, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand placed Indigenous people on reservations according to tribe. In fact, South Africa modelled its own passbook policies on what it saw in Canada, the US, New Zealand, and Australia, while its segregationist policies were modelled on American reservation systems.

The legacy of pass laws was evident in the unwritten rules and codes of communities such as sundown towns: that is, towns in the post-emancipation Americas where Black people knew they should not be found once darkness fell or they would make themselves vulnerable to bodily harm. Sundown towns and places like them were based on the assumption, long central to plantation logic, that Black and other nonwhite people are always out of place and do not legitimately belong anywhere that large numbers of white people reside, especially in places now assumed to be white homelands. In a post-slavery world, such practices work to devalue Black citizenship, rendering it less-than-citizenship.

The history that underwrites practices like carding springs from slavery and its afterlife. And, while these practices are now often recast as being about safety and security, the fact that they target the same groups of people as the earlier laws makes the truth abundantly clear to anyone who really cares to consider the matter. In Toronto, 27 percent of all carding documented in 2013 involved Black people, a vastly higher proportion than their 8.9 percent share of the municipality’s population. Indeed, it is the awareness that this dreadful history and its most brutal practices continues that motivates Black peoples’ demands for abolition. Carding and like practices create continuity between plantation slavery and the present moment, reminding Black people of their struggle for agency, autonomy, and ultimately, to own their own bodies.

A central problem with policing in its modern manifestation is that it cannot escape its founding in slavery, the aftermath of that founding, and how that founding continues to shape its present practices. The outcome of policing’s dreadful anti-Black legacy is that its practices seem inexorably more focused on those who were targets in its earliest days: Black people. Last summer, activist and organizer Mariame Kaba wrote in the New York Times that:

There is not a single era in United States history in which the police were not a force of violence against black people. Policing in the South emerged from the slave patrols in the 1700s and 1800s that caught and returned runaway slaves. In the North, the first municipal police departments in the mid-1800s helped quash labor strikes and riots against the rich. Everywhere, they have suppressed marginalized populations to protect the status quo.

So when you see a police officer pressing his knee into a black man’s neck until he dies, that’s the logical result of policing in America. When a police officer brutalizes a black person, he is doing what he sees as his job.

The desire to maintain a system of policing but reform it so that it is less biased—or, better yet, not biased at all—is central to any conversation about abolition and why it has emerged as such a powerful idea and demand. Since at least the 1970s, Black people across North America and beyond have come to understand that what is called police reform almost never has any impact on how they themselves are policed. In fact, one of abolition’s foundational notions is that policing as an institution cannot be reformed in any fashion that would make it amenable to Black safety, security, and ultimately, to Black life. What I therefore suggest is that the abolition of slavery was just the first stop on the abolition journey of, and for, Black people.

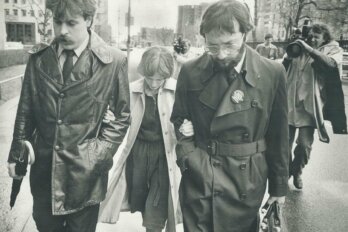

In the early 1990s, walking along Toronto’s Queen Street West near the corner of Portland Avenue, I was stopped by two policemen who demanded to know my name. I refused and instead asked them why they wanted to know it. My refusal led to the situation escalating quickly, and in a rather short space of time, I was surrounded by at least six other officers, making the total number eight, all with batons drawn. My white woman friend began shouting at me to tell them my name because “they are going to beat you up.” Above her plea I heard one of the officers say that they were looking for a white man in a pair of blue shorts who had tried to abduct a child. I was wearing blue shorts. But I was most definitely not a white man. This seemed to make little difference.

One can arrive at an abolitionist position independent of such personal experience, but encounters with police as a Black person definitely shape how you think of them and approach them thereafter. If you are Black and have ever been surrounded by police threatening to beat you up, your sense that slavery and the white master or mob have never actually disappeared is vitally manifest. Modern policing practices offer a significant and constant reminder to Black people that slavery isn’t that far in our past, less than 200 years for those of us living within what was once the British Empire; and, for African Americans, it is much shorter, little more than 150 years, and that’s not counting all the indignities and injustices that followed Jim Crow, making the historical timeline short enough to exist within living memories. My insistence that contemporary abolition is a continuation of an unfinished abolition movement is tied to both the sensation and reality of still being trapped by slavery’s ongoing practices.

Excerpted with permission from On Property by Rinaldo Walcott (Biblioasis, February 2021).