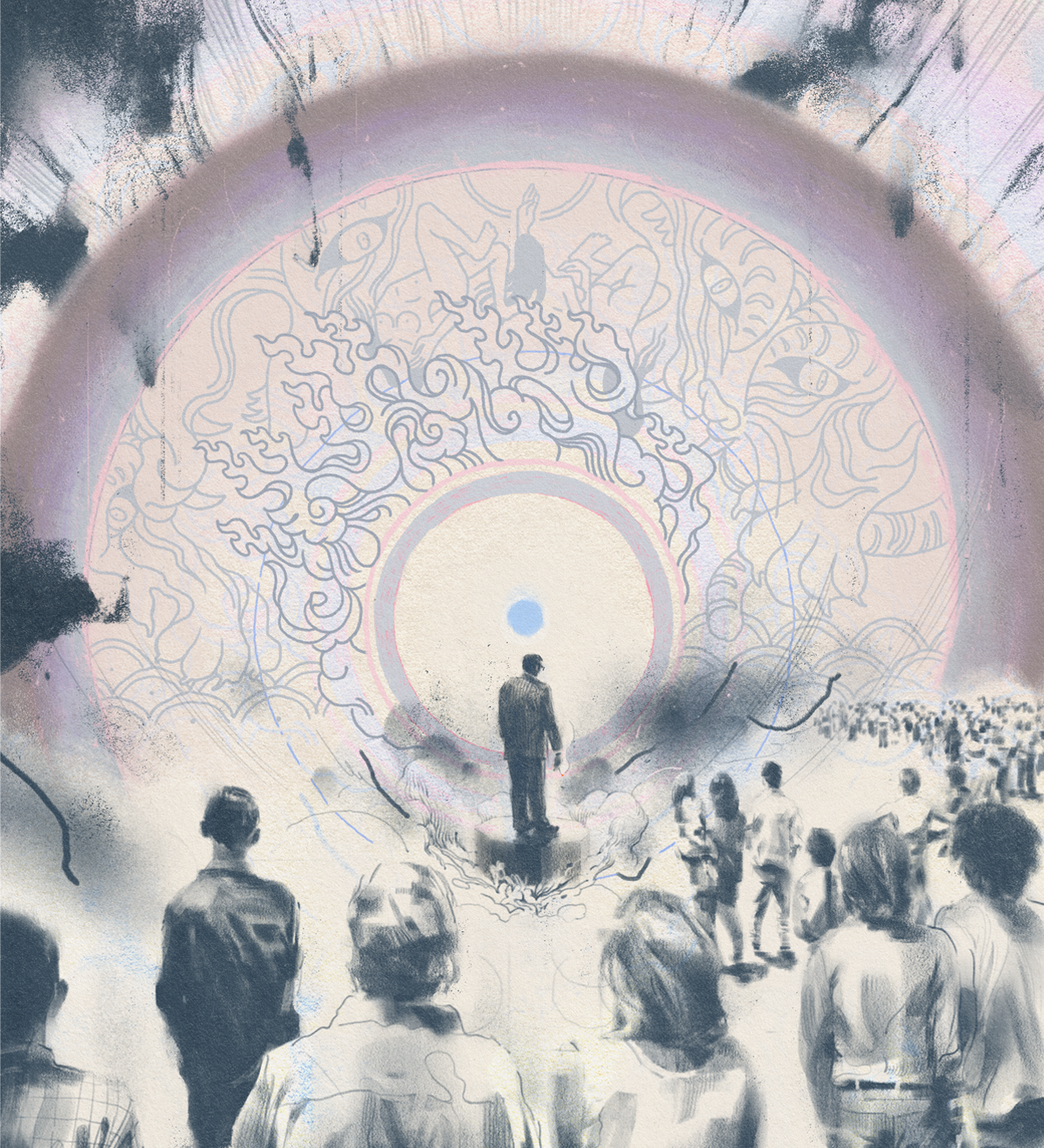

On April 4, 1987, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche lay dying in the old Halifax Infirmary. He was forty-seven. To the medical staff, Trungpa likely resembled any other patient admitted for palliative care. But, to the inner circle gathered around his bed and for tens of thousands of followers, he was a brilliant philosopher-king fading into sainthood. They believed that, through his reconstruction of “Shambhala”—the mythical Tibetan kingdom on which he’d modelled his New Age community, creating one of the most influential Buddhist organizations in the West—he had innovated a spiritual cure for a postmodern age, a series of precepts to help Westerners meditate their way out of apathy and egotism.

Listen to an audio version of this story

For more audio from The Walrus, subscribe to AMI-audio podcasts on iTunes.

Standing by Trungpa’s deathbed was Thomas Rich, his spiritual successor. Rich was joined by Diana Mukpo (formerly Diana Pybus), who had married Trungpa in 1970, a few months after she turned sixteen. Also present was Trungpa’s twenty-four-year-old son, Mipham Rinpoche. While the cohort chanted and prayed, twenty-five-year-old Leslie Hays listened from outside the door. Trungpa had taken her as one of his seven spiritual wives two years earlier. After being called in to say a brief goodbye, Hays walked out into the evening, secretly relieved Trungpa was dying. She would no longer be serving his sexual demands; enduring his pinches, punches, and kicks; or listening to him drunkenly recount hallucinated conversations with the long-dead sages of medieval Tibet.

Trungpa stopped breathing at 8:05 p.m. His attendants bathed his body in saffron water; painted prayers on small squares of paper and fixed them to his eyes, nostrils, and mouth; then wheeled the gurney into an ambulance to bring him home for a ritual wake. The cortège drove south, through the chilly night, toward Point Pleasant Park, the forested tip of the Halifax Peninsula. They pulled into a circular drive at 545 Young Avenue, a mansion dubbed “The Kalapa Court” after the fabled Shambhala seat of power.

Devotees rolled Trungpa’s body into the living room, which had been mostly cleared of furniture except for a Tibetan throne. They dressed the body in gold brocade and wrenched its legs into a crossed position to prop it up in a final meditation. In his death notice to the community, Rich stated that the guru had attained “parinirvana”—a transcendant state in which he would be free from the cycle of rebirth. (Years later, Trungpa’s personal doctor would cite liver disease from alcohol abuse as the cause of death.) “We vow to perpetuate your world,” Rich wrote.

Following Trungpa’s death, his Halifax congregation and hundreds of pilgrims flocked to Kalapa for five days of visitation. Temple guards in full military uniform admitted mourners around the clock. They filed into the dim room, through clouds of juniper incense, to chant, meditate, and bow in prostration. They believed that Trungpa’s consciousness was expanding into the infinite. One group member recalls throwing the windows open to the cold, wet air as a funk set in.

Some mourners knew Trungpa from his lectures on meditation. Others would have been enthralled by his 1973 book, Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism, which has sold 200,000 copies. Others still had likely attended the opening of his Naropa Institute, in Boulder, Colorado, in summer 1974, when 1,500 spiritual seekers had arrived to listen to him lecture beside countercultural heroes like Allen Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs. Many in the room in Halifax had uprooted their lives to live close to Trungpa, to work in his centres or transcribe his teachings. Some had pledged him their present and future lives through the ritual bonds central to Tantric religion. However they’d come, and for whatever reason they’d stayed, they were the core of what would become Shambhala International, a thriving network of more than 200 meditation centres and retreat destinations in dozens of countries. Headquartered in Nova Scotia, the organization’s motto is “Making Enlightened Society Possible.”

These days, Trungpa’s kingdom presents less like an “enlightened society” than it does a longitudinal study of intergenerational abuse and of how thin the line between religion and cult can be. In the thirty-three years since her husband’s death, Leslie Hays has felt her relief sharpen into fury. She has now emerged at the forefront of a movement of ex-followers who say that Trungpa’s public image as a spiritual genius has been used to hide a legacy of deception, exploitation, behavioural control, and systemic abuse. Their activism has organized around Trungpa’s son, Mipham, who eventually inherited his father’s empire and, in 2018, began to face his own public allegations of physical violence and sexual assault.

Over the course of two years, I’ve interviewed close to fifty ex-Shambhala members. They have told me stories of every type of mistreatment imaginable, from emotional manipulation and extreme neglect to molestation and rape—stories that turn Shambhala’s brand narrative, with its promises of utopia, upside down. Posting on the Facebook page created to support survivors like herself, Hays has shortened the group’s name simply to “Sham.”

Nearly 2,500 years ago, Buddhism began, in ancient India, as an austere movement of self-discovery that preached meditation and meticulous attention to ethics. Early converts radically rejected the classism and ritualism of existing religions. Today, Buddhist teachings hold that the mind is the first and central source of conflict and that meditation can help a person see reality more clearly, past their anxious desires. This, it is claimed, can decrease or even extinguish cycles of violence.

Mass-market visions of this modern Buddhism tend to orbit around stately figures, like the Dalai Lama and Thích Nhất Hạnh, the antiwar cleric from Vietnam nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize by Martin Luther King Jr. in 1967. American popularizers include Jack Kornfield and Sharon Salzberg, who co-founded the Insight Meditation Society, in Massachusetts, in 1975. Their professional trainings helped commodify and suburbanize ancient meditation techniques into secular wellness tools for use in self-help psychotherapy and even business coaching.

Trungpa’s organization grew in tandem with this popular interest. But his own reputation was built on the idea of enlightened chaos. He introduced his recruits to “crazy wisdom,” the practice of using bizarre and sometimes abusive methods to jolt devotees into higher states of being. In a series of 1983 sermons, he compared the attainment of spiritual wisdom to the act of rape. His butler recounted, in a memoir, Trungpa torturing a dog as a metaphor for how the unenlightened should be taught the uncompromising truths of Buddhism. Trungpa also taught a technique called “transmutation,” by which an enlightened person transforms the common or even the disgraceful aspects of their life into the sublime, thereby purifying themselves. The Tantric texts, logic, and ritual by which transmutation happens are all meant to be kept secret—which worked in Trungpa’s favour. His true ministry, if openly known, would hardly have ingratiated him to buttoned-down Nova Scotians.

Trungpa first scoped out Atlantic Canada in 1977. He travelled in the guise of a Bhutanese prince, making his disciples, during dinner, wear tuxedoes or evening gowns and white gloves. He loved the region’s remoteness, isolation, and rain. Trungpa found in Nova Scotia the perfect setting for a kind of spiritual invasion. It was sparsely populated, with one of the highest unemployment rates in the country. Citizens were dissatisfied with local government and ready for something new. He observed that Nova Scotians were psychologically “cooperative” and “starved” and opined that they needed “more energy to be put on them.” Back in Boulder, he declared that he could feel the same goodness in the earth in Nova Scotia that he remembered from Tibet, which he had fled in 1959.

Trungpa started frequenting Halifax as his eastern seat after devotees acquired the Young Avenue property. By the time Trungpa died, around 800 of his most ardent followers—mostly young, well-educated, middle-class white Americans—had settled on the East Coast life, laying down roots from Halifax to Pleasant Bay, a small community in Cape Breton, where they helped establish Gampo Abbey, now presided over by one one of Trungpa’s most famous former students, self-help author Pema Chödrön. Followers opened businesses in the burgeoning wellness sector, working as massage therapists, acupuncturists, and psychotherapists. In the summer, they gathered for communal events, like “seminary,” where Trungpa would teach Buddhist philosophy for days on end, and “encampment,” where members would march in parades and sing songs around campfires. Over the years, Maritimers joined the movement, drawn to its secular accessibility and devotional intensity, and soon came the first generation of born-and-raised Halifax Shambhala Buddhists, who joined the ranks of other so-called Dharma Brats in the US.

It was a community in thrall to Trungpa, a leader with an authoritarian streak whose eccentricities were typically passed off as transmutation. When he asked his dishevelled devotees to cut their hair and become professional, Trungpa—who had his suits hand-tailored on London’s Savile Row—was transmuting their late-hippie immaturity. When he dressed up like Idi Amin or rode a white stallion while wearing a pith helmet and phony war medals, he was transmuting the aggression of militarism. When he insisted that his courtiers learn Downton Abbey–style dinner etiquette, he was transmuting the colonial pretension that had almost destroyed the Asian wisdom culture he embodied. On the grandest scale, Trungpa saw Shambhala as a transmutation of the nation-state itself—complete with a national anthem, ministers, equestrian displays, an army, a treasury, specially minted coinage, and photo IDs.

But Trungpa’s transmutations didn’t stop there. They were also used to rationalize the sexual abuse he committed against countless women students—abuse that devotees justified as Trungpa transmuting the repressed Christian prudery of North America and turning lust into insight. Public evidence of this abuse was first published in a local Boulder magazine in 1979, but the most public and credible accusations came from Hays on Facebook, starting in 2018. Hays remembers Trungpa demanding women and girls at all hours of the day and night, some of them teenagers. He was not only prone to outbursts of physical violence but, according to Hays, her job as a “spiritual wife” (traditionally a consort for ritualized sexual meditations) involved offering Trungpa bumps of cocaine, which she remembers his lieutenants pretending was either a secret ritual substance or vitamin D. Hays’s entire relationship with Trungpa testifies to how he used his charisma to prey on followers.

Hays grew up in a Minnesota farm town and moved to Boulder, in 1981, to study journalism at the University of Colorado. She was twenty. Three years later, she took a nanny job with a couple who were devotees of Trungpa, moving into their house. She was asked to attend a summertime Shambhala training camp so that she’d be more aligned with the family’s values. That winter, the couple was hosting a wedding that Trungpa himself would be attending. They regaled her with stories of his “unfathomable” brilliance and asked her to prepare to meet him with meditations that involved visualizing him as divine. They took her shopping for clothes and taught her to walk in heels. In our conversation, Hays remembers being impressionable at that age and thinking it would be fun “to meet an enlightened meditation master from Tibet.”

At the wedding, Trungpa lavished attention on Hays, then showed up at her employer’s house the next day to propose that they marry. Hays was baffled, so he invited her to his home for a get-to-know-you date. Guards ushered her into his bedroom, where he was waiting for her, naked. That same night, he asked her to marry him again. Stunned, she agreed, believing it to be an honour, and for a while, there was a honeymoon-like feeling between them. But, after the first week, Hays told me, things started to go wrong. In the bedroom, Hays says, he would use a vibrator until she screamed out in pain. Then Trungpa started to punch and kick her.

“What Trungpa did,” says Liz Craig, “was create an environment for emotional and sexual harm in which nobody was accountable for their actions.” Craig worked as a nanny in Trungpa’s household. “If he’d been publicly violent, it would have been easier to identify him as harmful and Shambhala as a cult.”

Another ex-Shambhala student, who asked to remain anonymous, knows of several women Trungpa physically assaulted besides her. “He pinched me to the point of leaving dark bruises,” she says. I reached her at her office in Atlantic Canada, where she runs a practice as a therapist. She described one summer-long event in 1985 at the Rocky Mountain Dharma Center (now the Shambhala Mountain Center), north of Boulder. She was twenty-three at the time and was recruited to cook and clean in Trungpa’s residence. Trungpa’s “henchmen,” as she calls them, would circulate through the participants to find the women he desired. “The entire scene around him was sexualized,” she says. “Trungpa was basically the king of the universe, and any contact with him was a blessing that was going to guarantee your enlightenment and eternal salvation.”

It wasn’t only women who were caught in Shambhala’s abusive culture. Ex-member Michal Bandac, now living in Germany, says that, in the 1980s, Shambhala adults introduced him to cocaine use when he was twelve. The scene was considered safe, Bandac says, because they were taught that, “according to Buddhism, the children are always better than their parents.” Bandac’s mother, Patricia, was a senior Shambhala teacher for thirty years and the director of the Nova Scotia retreat centre. Since leaving Shambhala in 2015, she has struggled to understand how the group affected her family. While she wasn’t aware of her son’s exposure to cocaine, she does remember him telling her about Shambhala women in their thirties luring him into his first sexual experiences. “I was kind of shocked,” she says. “But I didn’t do anything about it. It was so normalized. There was statutory rape going on all over the place.”

Abuse continued after Trungpa’s death. In 1989, the New York Times reported that Trungpa’s spiritual successor, Thomas Rich, had been having unprotected sex with an unknown number of men and women while being HIV positive. This not only had gone on for years—Rich was suspected to have contracted the illness in 1985—but was likely known to senior leadership. Moreover, according to a 1990 article, Rich’s sexual history suggested such encounters weren’t always consensual. The media coverage forced Rich, in California at this time, into exile. After Kier Craig—Rich’s student and the brother of Liz, the Trungpa nanny—died of HIV/AIDS, likely contracted from Rich, even more Shambhalians fled the community. Program attendance and membership donations plummeted. The legal entities that held Shambhala’s assets were dissolved to avoid liability.

In the early 1990s, Tibetan clerics moved to stabilize Shambhala by certifying Trungpa’s son, Mipham, as a reincarnated master and the rightful heir to his father. It was an unlikely fit. Although in his thirties, Mipham didn’t have any of the expected monastic training and was not known for his charisma. Nevertheless, in 1995, Mipham was enthroned as sovereign over Shambhala and dubbed with one of his father’s own honorifics: “Sakyong,” which roughly translates to “Earth Ruler.”

As Sakyong, Mipham’s management approach was distinctly corporate. By 2002, he’d appointed the former public-relations head of Amnesty International as Shambhala’s new president. He replaced the mostly male administration with a more gender-balanced and international board of directors. Between 1999 and 2018, Mipham’s restructuring helped Shambhala’s global membership grow from under 7,000 to 14,000. Members participated in programs and training at outposts around the world, drawing an annual revenue of $18 million (US) in North America alone.

In the early 2000s, memories of Trungpa and Rich’s acts of sexual abuse seemed to have faded. Chödrön, Shamabhala’s self-help superstar based out of Cape Breton, lit out on an extraordinary run of mass-media success, appearing on Bill Moyers’ PBS miniseries Faith and Reason and eventually selling more than 1.2 million copies of her books in eighteen languages. Mipham also moved to shield what were reputed to be the most mystical elements of his father’s teaching content behind a pay-wall. He developed a pyramid-style series of training sessions and ceremonies only he could preside over as a kind of papal gatekeeper. Sporting brocade robes, Mipham came into his own as a regal figure, giving ritual initiations to new and old members and creating newer levels of secret practices for devotees to invest in. In 2005, he married Khandro Tseyang—the daughter of a Tibetan spirit medium who claims a royal pedigree. From the outside, things seemed to be looking up. But it was during these same Camelot years that Mipham allegedly assaulted attendants and students.

One of those students was Julia Howell, born into Shambhala in Nova Scotia in 1984. For children who grew up in the community, the promise and betrayal of their upbringing are difficult to separate. Sometimes, Trungpa’s world felt like a happy place. Some describe loving the free-range summer “Sun Camps.” They were consistently told that they were special—the “first Western Buddhists,” who would both embody and evangelize a new age. They had been given early access to authentic Buddhism, so they were told, and the teachings would take care of them. They were encouraged to internalize the group’s meditation techniques and use them whenever they lost their feeling of “basic goodness.”

When Howell was twenty-four, her mother was diagnosed with stage-four breast cancer. That fall, Howell applied for the Tantric training that was said to eventually lead to full citizenship within the mystical world of Shambhala. Her aim was partly to prepare herself for the coming loss and partly to join her mother in practices to prepare for death. Howell’s initiations involved vowing to perceive Mipham—now the group’s leader—as the gatekeeper to enlightenment. When her mother died, in 2010, Howell practiced with an intensity that matched her grief. Her ardour drew her closer to Mipham’s inner circle.

In 2011, Howell went to a party at the Kalapa Court, the enclave that Trungpa founded in Halifax. The occasion was Mipham’s daughter’s first birthday party. Howell says that, after his wife had gone to bed and most of the guests had left, Mipham, drunk, assaulted her. “I felt frozen, without agency,” she says. “I had taken a vow at seminary to follow his instructions like commands.” Alone, confused, and grieving her mother, Howell plunged deeper into her practice to make sense of it all.

“This liturgy embodies the magical heart of Shambhala,” announces the text Howell used. Written by Mipham, it proposes that the gifts of Tantric practice flow from developing a pure view of the master, then merging with him, body and mind. A key part of the ritual involves a purification fantasy. Howell was instructed to visualize light streaming down from a deity seated at the crown of her head. The light was washing away the karma of negative emotions, seen as dirt and muck pouring downward, out of her body and into the earth. Inevitably, this brought up traumatic memories associated with the assault. “It was an exercise in self-shaming,” says Howell. Her practice included visualizing Mipham, in royal attire, hovering above her head, then morphing into a fantastical bird, who entered her body and descended to dissolve into light in her chest. Should another assault happen, rather than experiencing it as a violation, she would will herself to see Mipham as the Buddha. “I was really training to think that rape is not rape,” she says.

After more than three years of trying to interpret the assault and justify Mipham’s behaviour, Howell decided to face him. It took several months to get the meeting through underlings. Mipham offered her a weak apology “about the whole thing,” as Howell remembers. She recalls him performing a healing ritual for her, then handing her a mala—a sort of Tibetan rosary—and saying, “This is for your practice.”

Through the summer and fall of 2017, stories about similar abuse ripped into other spiritual communities. In July, eight former attendants of the late Sogyal Rinpoche, a celebrated Buddhist teacher and the author of the bestselling Tibetan Book of Living and Dying, published an open letter describing decades of physical, sexual, and financial abuse by the religious leader. In November, Karen Rain alleged on Facebook that renowned yoga teacher Krishna Pattabhi Jois had sexually assaulted her and other women under the guise of “postural adjustments.” The children of Shambhala were watching. Andrea Winn, who had lived most of her life in Trungpa’s kingdom, decided it was time to speak out. (As Winn declined an interview, what follows is from publicly available records.)

“Something has gone tragically wrong in the Shambhala community,” wrote Winn in “Project Sunshine: Final Report,” a feat of guerrilla journalism published online in February 2018. The report featured five anonymous testimonies of assault, rape, and abuse that implicated unnamed Shambhala senior leaders as either enablers or perpetrators. “We have allowed abuse within our community for nearly four decades, and it is time to take practical steps to end it.” Winn, now fifty-three, included details about her own childhood sexual abuse by “multiple” community members and how, when she spoke out as a young adult, she was shunned. Her healing process led her to a counselling-psychology degree specializing in relational trauma. “One thing that is clear to me is that a single woman can be silenced,” she writes. “However, a group of organized concerned citizens will be a completely different ball game.”

Shambhala’s old guard likely knew that Winn’s report was coming. Three days before Winn published, Diana Mukpo, Trungpa’s wife by legal marriage, posted a letter to Shambhala’s community news website attempting to discredit Winn and the project, calling it a personal attack on her family. “When I first heard about Project Sunshine,” Mukpo wrote, “I thought it would be a wonderful way to embark on this important process. But now that I’ve seen its connection to the spreading of inaccurate, misleading facts, I no longer have faith in its ability to assist with this important task in an unbiased and honest manner.”

Winn teamed up with a retired lawyer, Carol Merchasin, who worked through the spring of 2018 to corroborate testimonies for a second, more explosive report. This round focused on allegations of sexual misconduct and assault against Shambhala’s leader, Mipham. Merchasin recounts that they reached out to the Shambhala Kalapa council to present the allegations prior to publishing and to encourage the organization to conduct an investigation. No one from the council would meet with the whistleblowers, but, according to Merchasin, the council hired a mediator who threatened her with legal action days before she and Winn planned to release the second report online on June 28.

Soon after the report was published, Mipham paused his teaching activities and issued a vaguely apologetic statement announcing that he was committing to a shared project of healing. “This is not easy work,” he concluded, “and we cannot give up on each other. For me, it always comes back to feeling my own heart, my own humanity, and my own genuineness. It is with this feeling that I express to all of you my deep love and appreciation. I am committed to engaging in this process with you.”

But Winn and Merchasin released a third report, that August, that included two further accounts alleging that Mipham had abused his power. Facing pressure from local and international media coverage, Shambhala decided to launch an independent investigation. The investigator’s conclusion, released in February 2019, was that Mipham had caused a lot of harm, and they encouraged him to take responsibility and “be directly involved in the healing process.” Two weeks after the findings were released, six former personal attendants to Mipham came forward with an open letter about their years of serving him. They described his chronic alcohol abuse and sexual misconduct, his profligate spending, and his physical assaults against Shambhala members. Six days later, forty-two of the organization’s teachers posted their own open letter, calling on Mipham to step down “for the foreseeable future.”

Suddenly, Shambhala leaders could no longer dismiss allegations of long-standing systemic abuse. The community’s Dharma Brats—those of Winn’s generation and later who’d grown up in the kingdom—now had a lot to say and a place to say it.

Sometime after the third report, Mipham fled Canada, with his wife and three young daughters, for India and Nepal. In February 2019, he issued a carefully worded acknowledgment of the abuse crisis, declaring that he would retreat from his teaching and administrative duties. “I want to express wholeheartedly how sorry I feel about all that has happened,” Mipham lamented. “I understand that I am the main source of that suffering and confusion and want to again apologize for this. I am deeply sorry.”

For more than a year, Mipham did in fact lie low, avoiding public events. But what is expedient in public-relations terms carries a steep price for Tantric devotees. For them, Mipham’s legal and administrative standing pales against the belief that his very body carries his father’s perfect revelation: the ritual keys to the Shambhala kingdom. It’s a Faustian bargain: they must petition for Mipham’s return regardless of what they know of him and despite the repercussions for people like Julia Howell. For those who believe that Trungpa’s revelation was messianic, the double bind is even tighter. It is said that Tantric teachings can be given only if devotees supplicate to the master for them. If they don’t literally beg for Mipham to come back, they’ll be personally responsible for the death of the enlightened society that was meant to save the world.

Last December, Mipham sent an announcement out over Shambhala networks featuring a cryptic love poem to his devotees: “Like a mist, you are always present. / Like a dream, you appear but are elusive. / Like a mountain, you remain an immovable presence in my life.” The rest of the letter offered family and business news and bemoaned the state of the world.

Two weeks later, a newsletter from the Shambhala board pledged support for Mipham’s return to ritual duty. The letter explained that 125 devotees had requested that Mipham confer the “Rigden Abhisheka”—an elite level of Shambhala teaching—in a bid to restore legitimacy to the damaged brand. In response, the Shambhala centre in France invited Mipham for the summer of 2020.

Pema Chödrön responded by stepping down from her clergy position. In a letter posted to the group’s news service in January, Chödrön said that she was “disheartened” by Mipham’s announced return. She had expected him to show compassion toward the survivors of his abuse, she wrote, and to do “some deep inner work on himself.” But it was the support from the board, she added, that distressed her more. “How can we return to business as usual?” she wrote. “I find it discouraging that the bravery of those who had the courage to speak out does not seem to be effecting more significant change in the path forward.”

The months that followed Chödrön’s letter have seen stock in Trungpa’s legacy continue to plummet. Shambhala centres in Frankfurt and New York issued rebukes of the board’s decision to support Mipham’s return. The board countered with a long-winded affirmation to steadying the course with reforms that stopped short of disinviting Mipham. And they kept fundraising.

Group members were further rattled when Michael Smith, a fifty-five-year-old former member of the Boulder Shambhala group, pled guilty to assaulting a thirteen-year-old girl he’d met through the community in the late 1990s. A similar case against William Lloyd Karelis, a seventy-three-year-old former meditation instructor for the Boulder Shambhala community, is set to go to trial next spring. Karelis is accused of repeatedly sexually assaulting a thirteen-year-old girl who had been assigned to him as a student in the 1990s. In February, the Larimer County Sheriff ’s Office closed a more than year-long investigation into “possible criminal activity” at the Colorado centres. They released a redacted file of their interviews with ex-members, which corroborated several of the abuse testimonies published by Winn and Merchasin, including Howell’s account of Mipham assaulting her in Halifax. No charges were filed.

On March 11, when the WHO declared COVID-19 a global pandemic, Mipham was leading a Tantric meditation retreat at a monastery in Nepal. Along with the monks, 108 pilgrims from seventeen countries attended—108 being a number of ritual perfection in Indo-Tibetan religions. Mipham’s blog reports a schedule of ceremonies, meet-and-greets with himself and his wife, and a sermon from the monastery’s abbot, who affirmed that Mipham’s leadership challenges were common to great Buddhist teachers. A wide-angle photo shows the middle-aged devotees, many of them white, sitting at attention in the shrine room. Each sports a lapel button emblazoned with what appears to be Mipham’s portrait.

After the retreat, which ended March 15, pandemic lockdowns shuttered Shambhala spaces around the world. With retreat and programming income slowed to nearly nil, the San Francisco centre notified members it was on the brink of insolvency, and the larger retreat centres asked members for a bailout. Mipham’s summer event in France was postponed, but he kept in touch with devotees by sending out pandemic practice instructions, including advice for devotees to chant the mantra of the Medicine Buddha, often used for healing.

On May 14, a group of the Nepal pilgrims paved the way for Mipham’s full return with an open letter reaffirming him as the organization’s leader. The writers claimed that “many of the allegations reported about the Sakyong were exaggerated or completely false” but that, “if someone felt hurt or confused by their relationship with him, he has done his best to address their concerns personally.” (Julia Howell confirmed that she has not heard from Mipham since the allegations were published.) Mipham’s Kalapa Court is wholesome, the letter continued, is responsive to the needs of followers, and remains the centre of the Shambhala universe. “There is no Shambhala without the Sakyong,” they wrote.

As of this writing, Mipham seems to be consolidating an inner core of devotees who will remain loyal to him and continue their journey toward his kingdom. And, while the remaining Shambhala administration claims to be working on reform policies, it’s not quite clear who will remain to enact them or keep the faith. I made multiple requests to Mipham for comment—directly and through various Shambhala administrators—about the Winn report, the independent investigation, Howell’s allegations, and his future teaching intentions. He did not respond.

For survivors of Shambhala, the reckoning continues—and with it, the struggle for recovery. Rachel Bernstein, a Los Angeles psychotherapist who treats ex–cult members, told me that it can be healing to reconnect not only with former members of the same group but also with former members of similar groups, so the person can understand that abuse patterns are standard and predictable. Janja Lalich, an expert on the effects of cults on children, argues that kids who grow up in a group controlled by charismatic leadership have almost no access to outside points of view or ways of being in the world. That’s why she encourages ex-members to reestablish secure bonds with family or those who knew them before they entered the group. But, for those born into a cult or recruited through their parents at a young age—as was often the case with Shambhala—this option is rarely open.

John (whose last name is withheld for reasons of family privacy) ran out of options completely. In 1980, at the age of twelve, he left his father and stepmother in Miami to join his mother, Nancy, in Colorado, where, as part of her program in Buddhist psychology at Naropa University, she had to complete a three-month retreat at the Rocky Mountain Dharma Center. While she was meditating from dawn till dusk, John was in residence. One night, he said, he was woken up by a man—a student in his mother’s cohort—assaulting him. John froze and pretended to stay asleep.

“After that first night,” John wrote in a statement to the Larimer County police, “he pursued me persistently for many days—at the meditation hall, in the shower room, and in the bathrooms. I was twelve and eventually I gave in.” The abuse continued, John remembered, for between three and six months. When he was thirteen, another Dharma Brat became John’s girlfriend. (She went on to become Trungpa’s sixth “spiritual wife” and later died by suicide at age thirty-four.) When John was fourteen, he wrote, another man at the Rocky Mountain Dharma Center—possibly an employee—abused him. Around this time, John first attempted suicide.

John told me his mother had gone to Trungpa and asked him what she should do about her troubled son. According to John, the leader told his mother it needed to be handled by professionals. Then Trungpa told her that she should attend another intensive residential seminary program. At nineteen, John wrote his mother a letter about his sexual abuse. She never answered it, he said. Years later, he found it, opened, in a family photo album. He ripped it up.

The abuse followed John into adulthood. Monique Auffrey was John’s partner from 2000 to 2004; they have a daughter together, now eighteen. Auffrey knew John as someone who was both victim and aggressor, who struggled with substance abuse and who used Shambhala psychology to try to persuade her that his domestic violence was acceptable. In 2011, John was charged with uttering death threats against Auffrey and their daughter as they attempted to leave Nova Scotia. “My main memory of him is fear,” she said by phone from Calgary, where she’s the CEO of a non-profit that provides services to women and children escaping domestic violence.

Auffrey said that, when she was pregnant, John forced her to take Shambhala training. She hadn’t been part of the Buddhist group before meeting John. She spoke of a cycle of abuse similar to that described by victims of Trungpa and Mipham—and similar to John’s own history as a victim: “He would be violent with me, attack me, insult me, threaten me, and then the response to dealing with that was to meditate and take more Shambhala lessons.” Auffrey remembered “There’s neither good nor bad” being a consistent mantra in the group. “It always felt like there was no accountability for anything, no matter what it was,” she said. “The group’s ideology allowed people to get away with rape, with assault, with crimes that the larger population would never put up with.”

In our second interview, in May 2019, John described a moment that suggested he had finally abandoned Shambhala teachings. He was driving one day and pulled over when he heard an interview with Leonard Cohen on the CBC. “‘These religions that promise you liberation and freedom,’” John recalled Cohen saying, “‘that you will be liberated from all of this: it’s a cruel promise that won’t come true.’ “I just burst out crying,” John said. “I was just so happy that he said something I was feeling all along. That there was a scam or some kind of package being sold. And he was saying: ‘In many cases, you feel things worse, more intensely, more painfully.’” A month after that interview, John died by suicide in his Dartmouth home.

By phone, Auffrey offered a personal assessment of her late partner that seemed to ring true for Trungpa’s legacy in general. “If people had rallied together to hold him accountable for his own behaviour,” she told me, “there might have been a chance that he could have gotten the help he needed. That’s the way I like to look at it—to hope that, with intervention, we can change the course of such a destructive trajectory.” It struck me, after we hung up, that her words sounded almost Buddhist in their mindfulness and compassion.

April 13, 2021: A previous version of this story stated that Nova Scotia had the highest unemployment rate in the country in 1977. In fact, it had one of the highest unemployment rates. The Walrus regrets the error.