There are maggots inside my gloves—this I discover after a few minutes of wear, when I get a prickly feeling in my fingertips. I quickly take the gloves off, flip them inside out, and rinse them in the river. I’m making my best effort at being tough and unflappable because I’m out with the Stó:lō fishing fleet, and fishers, as a rule, are tough.

Listen to an audio version of this story

For more audio from The Walrus, subscribe to AMI-audio podcasts on iTunes.

The gloves go back on. I reach into the net and pull out another writhing, surprisingly strong salmon. I’m on a flat-bottomed boat with just enough space for a very large ice-filled fishing tote, a couple of helpers, and the captain, all of us members of various Stó:lō First Nations.

The salmon goes from the river to the net to the tote, all the while heaving its body back and forth. Blood, ice, and water spray when the lid on the tote comes up—enough gets in your mouth that you can taste the salt of it. This is fresh water, so that salt taste is blood. The nausea from the maggots is a distant memory now.

As our boats come in, trucks swarm us, non-Natives looking to buy our fish. Our tote might hold $2,000 worth of salmon, but it’s all accounted for, and the government’s put off signing the contract that would allow us to sell any extra anyway. That night, as we’re washing down the boat, we overhear the news on TV: a spokesperson from the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) is accusing us and other Stó:lō people of illegally selling our fish, which we’re meant to keep only for our consumption.

Adding insult to injury, the spokesperson tacks on a warning to the unsuspecting public, telling them that we don’t know how to handle the fish properly; in another news report, they advised that any salmon bought from us poses a “significant risk to human health.”

Our catch is fine for us to eat, apparently—it’s just a problem for “human” health.

Stó:lō means “river people,” and this river is full of salmon—or, at least, it used to be. It’s our staple food, eaten smoked, baked, boiled, and candied. My grandma prized the eyes, plucked out and sucked on till they popped and released their fishy goo. My nephew goes for the eggs; he quite literally licks his lips at the sight of them. My uncle takes the best cuts to smoke outdoors with a closely guarded, centuries-old family recipe.

It takes a lot of nerve to say we don’t know how to handle salmon—but I suspect the reality behind that claim is that a great many Canadians can’t imagine us knowing anything independently, as Native people. It’s a way of thinking that is common enough among non-Natives, going all the way back to Christopher Columbus, who, describing his first encounter with “Indians,” gave us the backhanded compliment: “These are very simple-minded and handsomely formed people.”

Pretty and dumb.

Canadians, Americans—all of them treat us as the poor cousin of the human race. We’re seen as inferior Stone Age people, incapable of inventing or creating or even running our own lives. Look at how Indian Affairs or Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada or Indigenous Services puts training wheels on our nations. Look at how the DFO talks about us as if we were dangerous incompetents. Non-Natives act like we entered the world the day after they landed on Plymouth Rock, like they brought us into creation and are teaching us to be almost but not quite as good as them.

It’s a sentiment expressed openly in a 2012 editorial from a small-town Alberta newspaper, which declared, “It is our obligation, as trained and educated citizens, to become more involved with First Nations peoples and guide them towards becoming more responsible citizens.” The writer went on to ask, “Are First Nations people capable of understanding and assuming these responsibilities?”

Another way of saying that we’re pretty and dumb is to praise us for the “light touch” we had on our environment. “The native people were transparent in the landscape, living as natural elements of the ecosphere.” That assessment doesn’t trace back to Columbus, though, or even to those first colonizers. That was Smithsonian botanist Stanwyn G. Shetler, writing in 1991, for the occasion of the 500th anniversary of Columbus’s voyage. In effect, he and many others think that we had the same impact on our continent as squirrels—which is to say that, even though we were here, we didn’t occupy our land in any meaningful sense. It belonged to nobody.

Sadly, that view of Canada and the Americas as terra nullius—no one’s land—dominates among non-Natives. But what do the facts say? The facts say that, far from them bringing us into the world, and far from us being the pretty and dumb cousin to proper humans, it’s only with our knowledge and creations and work that their world was able to come into existence in the first place. They didn’t hand us the keys to the modern world—they took from us the tools that built its foundations.

The spokesperson for the DFO didn’t emerge out of the earth fully formed: they and their way of thinking came from somewhere. Look to the person who trained them, and the one who trained them. If you keep going back, one boss after another after another, you will eventually end up, at noon on Monday, July 30, 1827, on the Cadboro, a schooner owned by the Hudson’s Bay Company that has anchored in the Fraser River—for us Stó:lō, this is where Canada begins. The boat carries a mix of Quebecois, Hawaiian, British, Métis, Abenaki, and Iroquois labourers. These men have come to build Fort Langley, where British Columbia will one day be founded as its own colony. But—though their descendants might tell you the land was untouched—they are in S’olh Temexw and they work opposite Kwantlen, which is my home First Nation. The construction they start that day is the first act of foreign rule in our country.

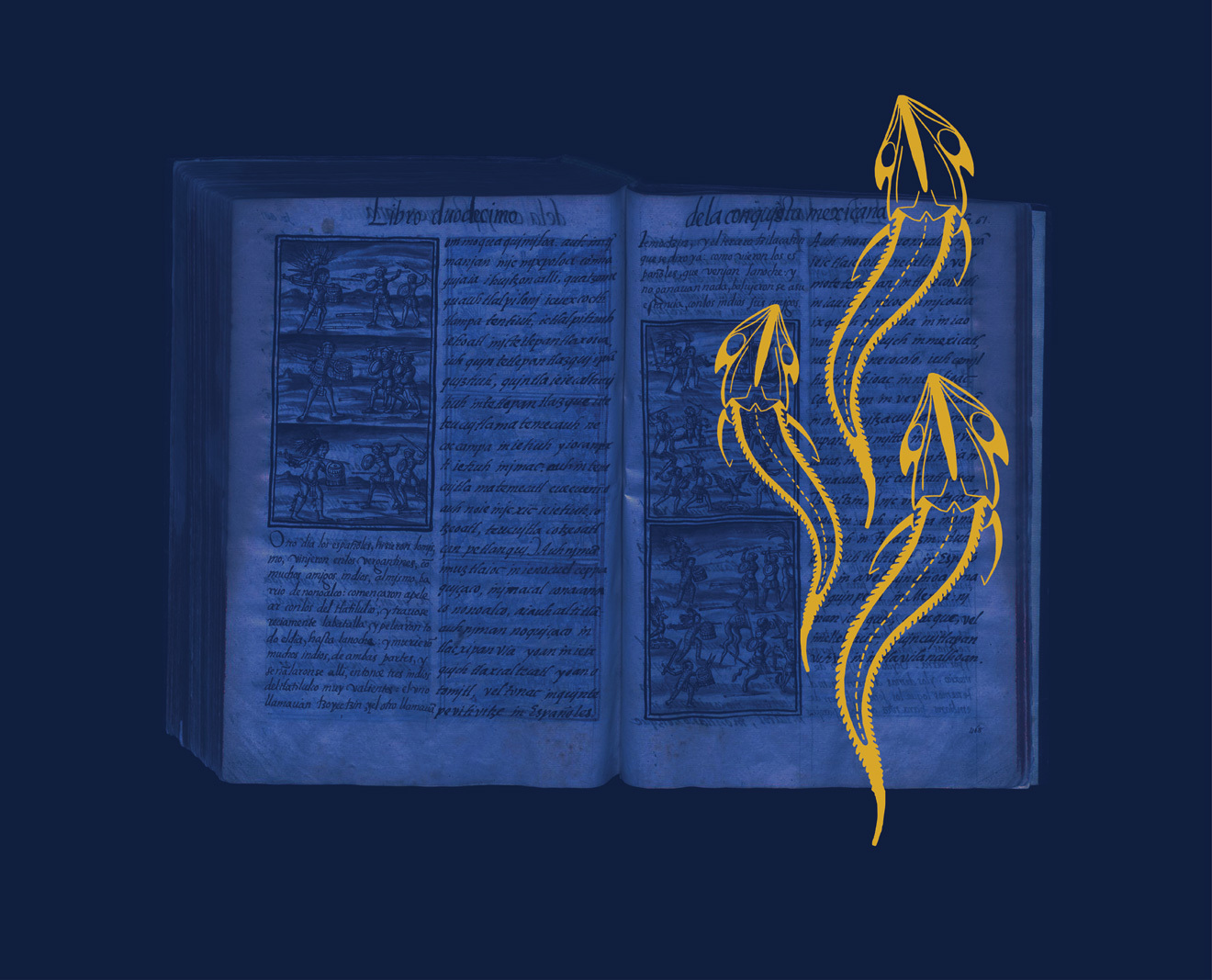

George Barnston was a surveyor for the Hudson’s Bay Company and an important (if undervalued) member of the Cadboro’s crew. One of Barnston’s duties was to keep Fort Langley’s logbook, a diary of sorts. Back in July 1827, Barnston briefly mentioned the settlement but spent the majority of his entry discussing the fishing practices of my ancestors and the ancestors of those I was catching salmon with:

We procured from the Indians today for the first time a supply of fresh sturgeon, which are as large here as in the Columbia. The Spears made use of in killing them are sometimes fifty feet long, running into a fork at the end, on the two claws of which, are fixed Barbs pointed occasionally with iron, but oftener with a piece of shell. When the fish is struck the Barbs are unshipped, and being attached in the middle by a cord which is carried along the spear and held by the Fisherman, they are drawn across the wound in the same manner as a Whale Harpoon, and the Fish when exhausted is drawn up and killed.

It makes sense that the very first meaningful interaction between our two peoples was about food harvesting. It is alluded to in our name for them: xwelítem—the hungry people. Our ancestors gave that name to the starving white miners who came begging at our towns for food during the first winter of the Fraser River gold rush, and it’s a name that has come to be used for all non-Natives.

On Tuesday, August 14, Barnston records the ongoing construction of the fort and the first purchase of dried salmon from our people. That salmon would undoubtedly have come from my family’s stores and would be prepared in the same way as now.

How to prepare a salmon: the fish is gutted and the head and tail are removed and saved, along with the roe. The sides are then salted, rubbed with a mixture of local herbs (the secret part of the family recipe), and roasted over a fire for five minutes per side before being cold smoked over cedar. When complete, the flesh is slightly sticky and sweet—smoky, but not too much.

Stó:lō of that era ate their salmon with a salad of local greens, berries, and a root vegetable called skous, which tastes similar to a Yukon Gold potato. Barnston records the skous-harvesting season in his journals along with many other natural observations. His time in my country inspired him to become a naturalist. He amassed a vast collection of flora and fossils from the Americas, specimens that are housed at Montreal’s Redpath Museum and have found their way into the collections of the Smithsonian and the British Museum.

While in my country, Barnston married Ellen Matthews, the daughter of a fur trader and a wealthy First Nations merchant from the Chinook town of Clatsop, Oregon, which is down the coast from Fort Langley. (Clatsop is an anglicized Chinook word, łät’cαp, which means “place of dried salmon.”) They had eleven children, the two most notable being James Barnston and John George Barnston. James earned a degree in medicine and was the first curator of McGill’s herbarium, which the university now advertises as “the oldest research museum of dried plant specimens in Canada.” John George Barnston ran, successfully, in an 1872 by-election, which becomes very significant if you remember that his mother is Ellen Matthews, daughter of a Chinook merchant—making John George one quarter First Nations and the (hitherto uncredited) first Indigenous person to serve as a member of the BC legislature.

John George would likely reject that distinction: the Barnston children appeared to be entirely alienated from their Indigenous heritage. This is exemplified in James’s description of the pursuit of botany in a lecture to his students at McGill. The Canadian wilderness, he told them, is a “paradise . . . filled with creatures yet to be named.”

If you have a moment, browse Wikipedia’s “Timeline of Historic Inventions.” It includes the cultivation of rice in China, the invention of the wheel in Mesopotamia, and hundreds of other creations from all over the world—but none from the Americas. Believing that we’re transparent in the landscape renders our achievements invisible to the world. Redo the timeline with a knowledge of our peoples, and the cultivation of corn and potatoes will earn a mention, and the creation of the three-dimensional khipu writing system will appear. The invention of spindle whorls among the Salish, Aztec mathematics, and Haudenosaunee constitutional federalism will all have a place.

Contrary to what people like Barnston thought, we have names for everything here—many of them representing achievements that should have a place next to any Mesopotamian creation. These names persist even today: potato, maize, avocado, tomato, tobacco, chocolate, quinoa, quinine, cocaine, and many more. Things created by Indigenous peoples.

Research in recent decades has shown the extent to which the environment in the Americas was crafted by Indigenous people. A 2017 study, published in the journal Science, found that the single greatest artifact of Indigenous agriculturalists is the Amazon rainforest: researchers identified eighty-five different fruit- or nut-bearing trees that were domesticated by the Amazon’s Native inhabitants. What is seen by some as a wilderness is actually, over large tracts, an overgrown orchard—one made wild by the disease and depopulation that came with European contact.

The process of domesticating plants is what turned a bitter red berry into strawberries. It’s how the people of the Balsas River Valley, in southern Mexico, turned a wheat-like grass with small grains, called teosinte, into corn. It’s how ancient civilizations from Ancón-Chilló, in modern-day Peru, made a relative of toxic nightshade into potatoes. It took the raw ingredients of this continent and, through the patient work of generations of Indigenous farmers, created half of the fruits and vegetables cultivated in the world today. Pretty and dumb, indeed.

Native innovation and technology also developed new ways of growing food. It was the Quechua who pioneered the use of “wanu,” or guano—nitrogen fertilizer made from bird droppings. Wars were fought and empires built when the foreigners discovered its value: in 1856, the US passed the Guano Islands Act, granting any American citizen the right to seize any unclaimed island anywhere in the world if it was found to have guano on it. In 1899, three enterprising Americans asserted these rights over Fox Island, a few kilometres offshore from mainland Quebec. The fate of that claim is unclear, but eight islands claimed under the Guano Act remain under US control to this day. It’s thanks to guano (and the artificial versions of it that followed the resource’s depletion at the end of the nineteenth century) that non-Native farmers caught up with their counterparts in the Indigenous Americas and more than doubled their agricultural output in the course of a century.

European farmers of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries had to leave as much as half of their fields empty at any time so as not to exhaust their growing potential. They were also overreliant on grain as one of their few sources of nutrition. The result was that, in England alone, between 1523 and 1623, there were seventeen major famines. The addition of Indigenous agricultural methods and foods domesticated by Indigenous people changed that. Where in the past, a study in Nature found, European farmers could feed 1.9 people per hectare, with our help they could now feed 4.3. Writing in Smithsonian Magazine, Charles C. Mann concludes that, with Indigenous peoples’ sharing of their domesticated foods and agricultural technology, “the revolution begun by potatoes, corn, and guano has allowed living standards to double or triple worldwide even as human numbers climbed from fewer than one billion in 1700 to some seven billion today.”

These foods and technologies weren’t gifted to Europe: they were sometimes stolen, but often they were the objects of trades, like those Barnston was tasked with documenting at Fort Langley. On Thursday, August 2, 1827, Barnston records the following exchange: “Two hundred weight of sturgeon was traded for, with red baize, axes, knives and buttons which, with the exception of blankets and ammunition, are articles in greatest request with the Indians here.”

Barnston is describing a trade that forms part of what is called the Columbian Exchange. To non-Natives, this is an event characterized by the transfer of advanced European technology and practices to the Americas in exchange for our land. They think of it as something like a gift, an act of supreme benevolence. Gratitude was and continues to be expected.

Back during the Columbus quincentennial, one commentator wrote, in the Ottawa Citizen, that “whatever the problems it brought, the vilified western culture also brought undreamed-of benefits, without which most of today’s Indians would be infinitely poorer or not even alive.”

Non-Natives tend to exaggerate the difference between their cultures and Indigenous cultures, and they downplay the dynamism of Indigenous peoples. In a recent discussion about Native people on his podcast, Joe Rogan said: “If no one came to America, if the world just stayed in Europe and Asia and the way it had been before Columbus and before the Pilgrims and all that shit, these people would probably still be living like that. . . . It’s incredible to think there were millions and millions of members of different tribes living in this country, basically like Stone Age people.”

These people are wrong for too many different reasons to count, but two stand out. The first is what exactly Europe brought to the table. Before 1492, the average English family lived in a windowless shanty with dirt floors and a grass roof. They made their clothes at home and, when they weren’t starving, subsisted on a few domesticated animals and gruel for much of the year (there were some vegetables in the warmer months). Looking back at Wikipedia’s “Timeline of Historic Inventions,” in the decades preceding first contact, one of the greatest technological advancements in Europe was the button.

Non-Natives like to think that the Mayflower had Wi-Fi, that the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa María brought with them consumer goods, Facebook, and nuclear medicine. In reality, they brought very little from Europe that Natives wanted beyond weapons and metalwork.

The second error non-Natives make when discussing the Columbian Exchange is in omitting what Indigenous peoples sent to Europe. They didn’t just get our land. What we sent in agricultural know-how was the key to the growth in the centuries that followed their arrival in our countries, raising them out from beneath their grass roofs and setting the stage for the world’s material development.

The Department of Fisheries and Oceans swarms our fleet the next few days out on the river, looking for any little mistake in order to file charges. Video emerges on Native social media showing DFO officers fighting Native fishermen and going for their guns.

Their agents meet us onshore and try to trick us into selling to them. They do this with all the guile and subtlety of Inspector Clouseau, and no one falls for it. When that fails, they invent charges, claiming illegal nets are being used. DFO officers move against the captain of the fishing boat I was on. He is arrested, his nets destroyed, and his catch thrown into the river; he is later sentenced to community service.

Again, another insult: that we don’t know how to manage our own resource. So they tell us when to fish, what to fish, how to fish, and why to fish. Within their narrow limits, we exercise our rights on a river named after us.

Among our catch is a sturgeon—two metres long and impressive looking, like the sturgeon that made up our first recorded trade with the xwelítem, the hungry people. Unfortunately, due to the DFO’s incompetence, our sturgeon are now nearly extinct, so once we are clear of the nets that trail behind the boats, we are forced to return it to the river. It jumps above the waves and then swims off.