A patient bursts into the hospital, upset, convinced she has ovarian cancer. She says she has proof: a blood test, ordered by her family doctor, shows elevated amounts of CA125, a protein sometimes found on cancerous cells. But the emergency doctors learn that neither the patient nor her immediate family members have histories of ovarian cancer, which means she should never have undergone the test in the first place: it is not designed for the general population. The patient had heard about the test and asked her own physician to perform it, just in case, setting off a chain of events that led her to the hospital.

Raj Waghmare, an emergency-room doctor in Newmarket, Ontario, says he has repeatedly seen situations like this one—patients rushing to the ER after receiving unnecessary lab results. CA125 testing is most often recommended for women who have or are suspected to have ovarian cancer: it can help determine whether a treatment is working or the cancer has reappeared. But, when used to screen patients who don’t have that history, it can deliver false positives, leading to unwarranted panic and interventions. After conducting a pelvic ultrasound, hospital staff assured the patient that she was fine and sent her home.

Lab tests like the one for CA125, which typically involve drawing blood and examining it for clues about a patient’s health, are vital tools when it comes to monitoring and diagnosing patients. However, a growing body of research, going as far back as the 1970s, suggests that these tests are regularly ordered without cause, which can lead to more harm than good. Today, organizations such as Choosing Wisely—a US-based health-advocacy initiative—have sprung up to educate patients and doctors about the problem. But, in Canada, unnecessary and “inappropriate” tests are on the rise, says Christopher Naugler, a University of Calgary researcher and pathologist. According to a February report Naugler co-authored for the C. D. Howe Institute, an estimated $5.9 billion is spent annually on lab tests, and that cost is rising steadily. A meta-analysis in 2017 found that up to 56 percent of tests each year are ordered against medical guidelines.

Medical advancements have led to a growing number of available procedures. One reason for the increase in testing is simply that patients have more options, says Naugler. Another factor could be the increased burden of disease as demographics shift in Canada: older people are more likely to get sick, and doctors may order more tests to figure out what is ailing them. Yet another cause, Naugler says, is the changing relationship between patients and their health care providers. As the internet has opened up a trove of accessible (if questionable) information, the average person has taken more ownership of their health care. Patients have greater awareness of the existence and uses of certain tests, and they are increasingly asking their doctors to order them. Physicians, meanwhile, might acquiesce when guidelines don’t explicitly recommend against doing so, or because they want to please a nervous patient.

In Canada, there has been an exponential increase in patient requests for vitamin D testing, for example. Talk-show hosts and internet personalities—including Dr. Oz and Gwyneth Paltrow—have started to preach the vitamin’s benefits to followers, who then might decide to get checked by a doctor. But recent research suggests that few people with low vitamin D levels are in need of medical attention. A bit more sun and a few more servings of salmon are simpler—and cheaper—fixes. Choosing Wisely Canada, which is organized by a team from the University of Toronto, St. Michael’s Hospital, and the Canadian Medical Association, says vitamin D tests are unlikely to change a doctor’s advice. They could also lead to needless or harmful treatments. (Overdiagnosis can lead to overtreatment, and too much vitamin D from supplements or injections could damage kidneys and other organs.)

Research has shown that “defensive” health care approaches, which involve the excessive ordering of diagnostic tests, don’t necessarily increase the chances that rare conditions will be caught. They do, however, increase the likelihood of overdiagnosis. False positives are unavoidable: “That’s just the way lab testing works,” Naugler says. A 2018 study, co-published by the Calgary-based doctor, found that, of all the worrisome (or “abnormal”) results from lab tests ordered by family physicians, more than half could be false positives. A patient may undergo a test, Naugler explains, “and it leads to something else, which leads to something else—and the initial test should never have been done.” This process can be costly and cause the patient serious anxiety. It can also lead to further health problems—or, in the most extreme cases, death.

Based on health data from hospitals and physicians, it’s estimated that, each year, patients collectively undergo more than a million tests or treatments that don’t help or may be harmful—from X-rays and MRIs to blood transfusions. Lab tests are arguably the most dangerous of the bunch: nearly three-quarters of medical decisions are made based on their results, making the overall downstream effects of their overuse immeasurable.

It may sound counterintuitive to complain about medical tests. Any fan of House or Grey’s Anatomy is familiar with the romantic narrative of the physician who orders slate upon slate of tests to pin down an elusive diagnosis. The implication is that doctors who order more tests are being more attentive—that the more tests are done, the less likely the medical team is missing something crucial. The reality of lab testing, however, is much more complex: in medicine, context can be everything, and results mean little without the relevant patient history.

Waghmare offers an example: a seventy-six-year-old in the ER, complaining of shortness of breath, was diagnosed with emphysema. He was given an X-ray, which revealed a shadow in his chest. Results from a blood test led to a colonoscopy, during which the man went into cardiac arrest. During his extended stay at the hospital, the patient caught a superbug that eventually killed him.

While the initial X-ray and blood work had not been “inappropriate”—there are no guidelines against ordering these tests under such circumstances—Waghmare says the case demonstrates that ordering more procedures is not necessarily best when one considers the risks. Longer hospital stays can increase a patient’s chance of infection: every year, about 220,000 Canadians contract infections at hospitals, and 8,000 more die because of them. “I wonder what might have happened if I’d just listened to his lungs, presumed he had pneumonia, and given him a course of antibiotics,” Waghmare later wrote about the case.

Most patient harm caused by overtesting is not so severe, but follow-up tests can be painful and invasive. For instance, patients who receive routine pap tests when they are below the recommended minimum age (twenty-one to twenty-five, depending on the jurisdiction) are increasing their statistical likelihood of encountering false positives—including having their noncancerous HPV confused with the cancerous kind. This could lead to repeated biopsies of the cervix, Naugler says, and even the removal of the top of the cervix, which can affect subsequent pregnancies. There’s also the anxiety that comes with waiting for unnecessary lab results: patients might spend weeks or months in anguish over the results of tests they were never supposed to take. That anxiety might lead to loss of sleep, changes in diet, and other behaviours that could affect their health.

As provincial governments across the country scramble to tighten their health care budgets, the rising costs of lab testing are gaining awareness. In August, in an effort to save $120 million annually, the Ontario government delisted from its health care coverage several tests—including MRIs and CT scans for joint pain—that were considered outdated or unnecessary. Attempts at scaling back, however, are sure to be challenged: it’s hard to convince the public that less health care can be a positive change.

To start tackling the problem of inappropriate testing, the C. D. Howe report recommends introducing the concept in medical schools. Physicians should have their ordering practices compared to those of their peers to identify any outliers.

Another solution involves technology, such as digital request forms, that requires doctors to submit reasons for ordering tests. According to a 2017 study on vitamin D testing by Naugler and his team, when physicians are obliged to justify ordering a particular test, they are much less likely to order it unnecessarily.

Meanwhile, initiatives like Choosing Wisely are working to raise awareness among doctors and patients. One of several pamphlets it offers outlines which surgeries require lab tests in advance and which usually do not (typically low-risk surgeries, such as eye, skin, or hernia operations). Choosing Wisely advises patients to always ask their doctors questions about procedures: Do I need this test or treatment? What are the downsides? Are there simpler, safer options? And what happens if I wait or do nothing?

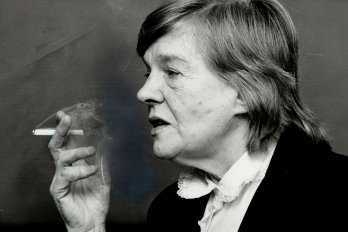

It’s in this conversation that Wendy Levinson, who chairs Choosing Wisely Canada, sees the greatest opportunity for change. “People think that, if they went to the doctor and didn’t leave with a prescription, they didn’t get care,” she says. But prescriptions and procedures are just two pieces of patient care. Physicians need to foster healthier conversational relationships with patients so that patients can fully understand the risks and make more informed decisions about their own health. Only then, she says, can patient care really improve.