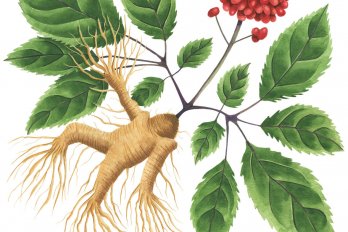

Steep me like tea in a scalding sea.

Pour the brew on the roots of a tree.

Look up, up, up for brush

when you worry. It’s me.

Follow my coniferous coif home, but

cut me down if need be. Chopping

spree. Decisions are arduous; love

can be trigonometry. All straight lines

can be expressed as y=mx+b,

but we are not formulaic, you see?

We leave Points A and Points B

to the petite bourgeoisie, to the

rampart hearts that beat, badly,

in barracks, under lock and lost skeleton key.

Sweet tea, when you need a hand,

grasp my trunk tightly.

Call that synecdoche.

Call it “come sit next to me.”

Call it: I know you’d undrape

the nape of your neck for me,

would unwind the twine

and silver filigree that stitch

your scar tissue into Body, into

your Möbius-stripped-down topology.

Climb on top of me. Open. Let’s oxidize our insides out,

if we have such sacred architectures.

I pray only to wordplay. Am I wrong

to fetishize fluidity? Strength? To steep

your oolong too,

too long?

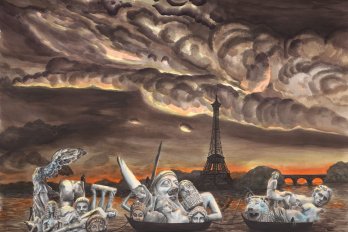

A chemist-chef has concocted a double-edged tea:

a drink that’s half hot, half cold.

To which side of the cup would an optimist first lend her lips?

You and I wouldn’t choose; we’d sip

from both parts at once.

My partner gave me the chemist-chef’s cookbook.

Your ex gave you many of your favourite teapots.

Dr. Phil would ask what in tarnation we think we’re doing.

In his experience, too many chefs

means there’s trouble brewing.

But what is excess? What is shame? Is it hot

and cold kissing? Is it the kettle wet-hissing your name?

The secret of the queer tea: the cup is filled with a liquid gel

divided into two temperatures, so that the potion’s imperceptible

viscosity prevents mixing—just a gel, for all that fuss, just

a semisolid masquerading

as fluid,

as us.