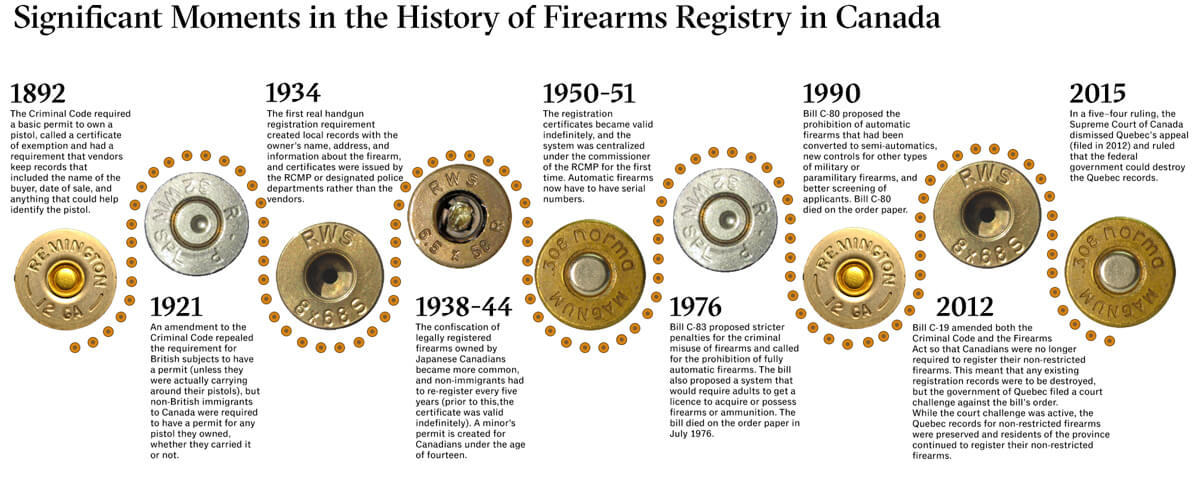

In late January this year, the Quebec government brought the Firearms Registration Act into effect. It requires the owners of all non-registered firearms to register such guns in a database available to law enforcement officials. In other words, the provincial government introduced a long-gun registry.

The coming into force of the Quebec-only version was a bureaucratic moment, timed neither to coincide with past shooting tragedies nor to respond to new ones. The legislation, moreover, is about as non-judgmental as one could want: there’s no fee to register, and the penalty for non-compliance is a fine (anywhere from $500 to $15,000, depending on the type of infraction). If someone repeatedly refuses to register, the courts can seize and eventually confiscate their guns. But the legislation doesn’t provide for jail terms for chronic offenders.

This law, applicable only to a portion of Canadians, represents the end point of a horror show that began on December 6, 1989, when Marc Lépine walked into Montreal’s l’École Polytechnique and killed fourteen women (and then himself) with a Ruger Mini-14—a rifle with an automatic reloading mechanism. The massacre predated Columbine—considered by many to be the event that spawned the mass-shooting epidemic—by a decade.

In the immediate aftermath of the Montreal shooting, the Canadian public was galvanized into action. Ottawa established a national gun registry in the 1990s, under Bill C-68, which allowed police to keep track of individual firearms and also know if one might be present in a location where a crime is taking place. Police chiefs across the country issued press releases confirming the usefulness of a national database that tracked firearms, stating in 2010 that Canadian police checked it about 11,000 times a day. The registry process, however, became mired in mismanagement and overspending and became a talking point for Reform Party and Conservative Party politicians, as well as rural voters—a wedge issue almost as salient and bait-y as fixing the Senate.

The politically motivated death of the federal registry should serve a reminder that Canadians are not nearly as clear-eyed about these issues as we like to imagine. While last month’s shooting at Florida’s Marjory Stoneman Douglas high school evoked a wearyingly long list of other US shootings, some of them very recent, Canadians should remember that such terrible crimes have also occurred here, including one just last year: the Quebec City mosque shooting, which left six dead. All Canadian gun-related killings, in fact, should force us to ask whether our own firearms laws are as robust as many assume them to be.

Thanks to the fervent and infectious activism of a group of Stoneman Douglas students, the political momentum for tougher gun control in the US seems to have reached a tipping point. A Quinnipiac University poll conducted in February in the US showed that 97 percent of respondents supported universal background checks, 67 percent were in favour of a ban on the sale of assault weapons, and 83 percent were in favour of mandatory waiting periods for all gun purchases. (The phone poll surveyed more than 1,200 registered voters.)

Indeed, at a time when so many people have been riveted by the electrifying determination of the young survivors of the Florida shooting, it’s easy to overlook the fact that the Liberal government of Justin Trudeau, with its cloying self-righteousness, has studiously avoided most of the gun-control reforms it promised in the 2015 election. “The gun registry saves lives,” Trudeau said in 2011 on the anniversary of the Montreal massacre. Today, however, he’s largely dismissed long-gun registries as ineffective and, perhaps more saliently, politically divisive.

That’s not to say the Canadian government has done nothing when it comes to guns. Following last October’s almost surreally horrid massacre in Las Vegas, some pundits and gun-control groups began slagging the Liberals for their inaction on those 2015 election promises. About a month later, public-safety minister Ralph Goodale trotted out the government’s response: a guns-and-gangs summit and $327 million over five years (with $100 million annually thereafter) to boost gang-related local law enforcement efforts. Communities, the minister’s presser emoted, “are suffering the devastating effects of gun violence and gang activity.”

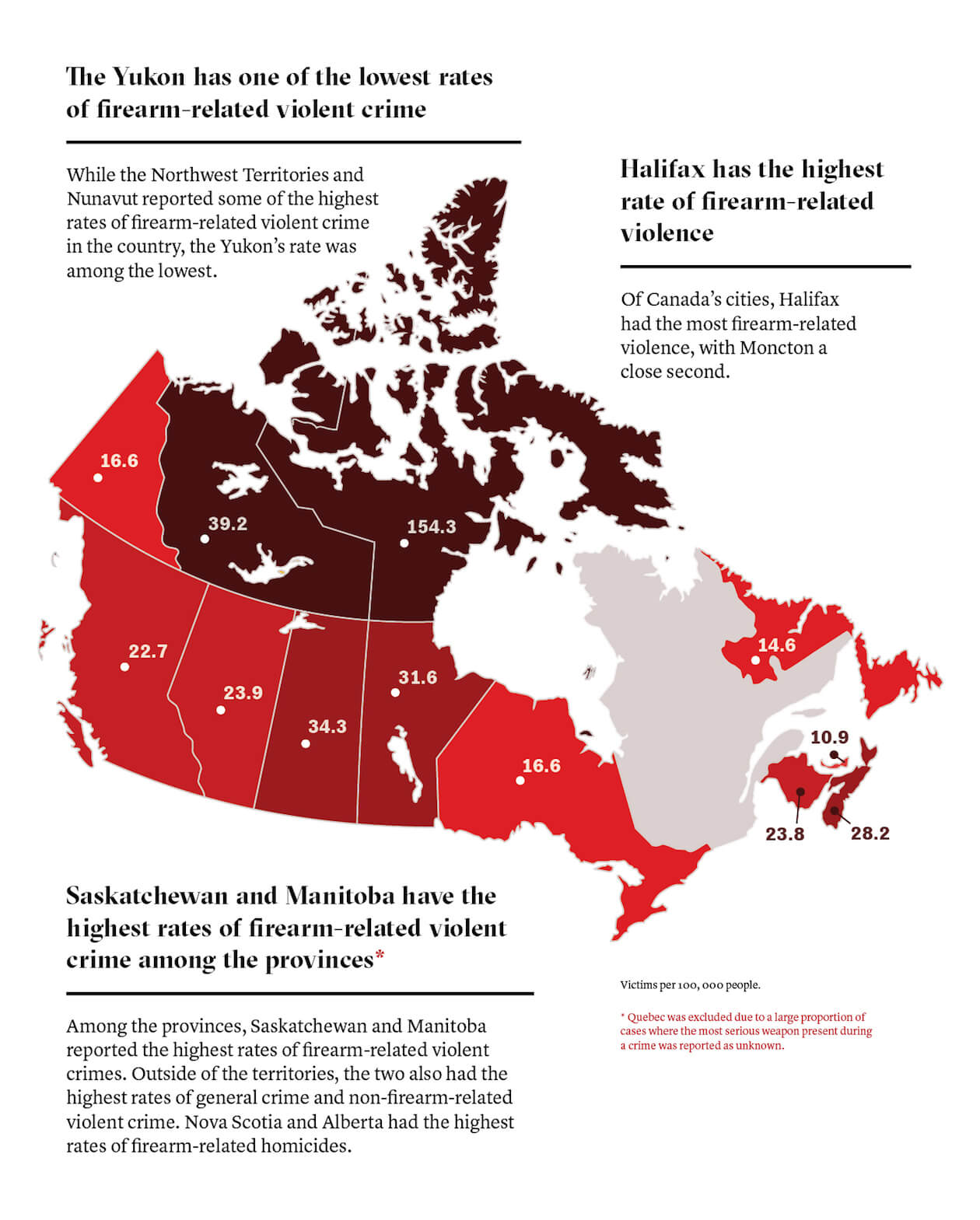

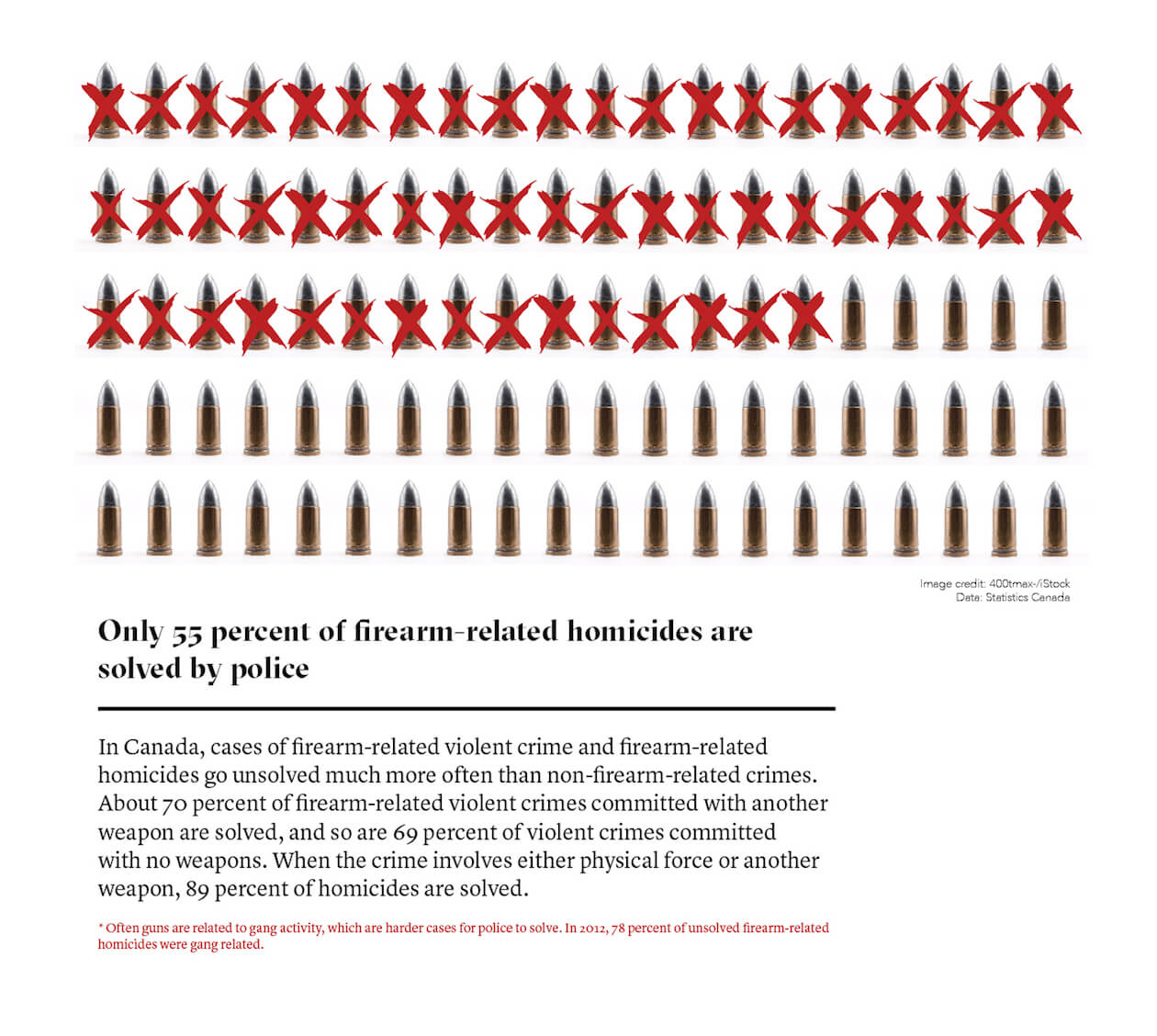

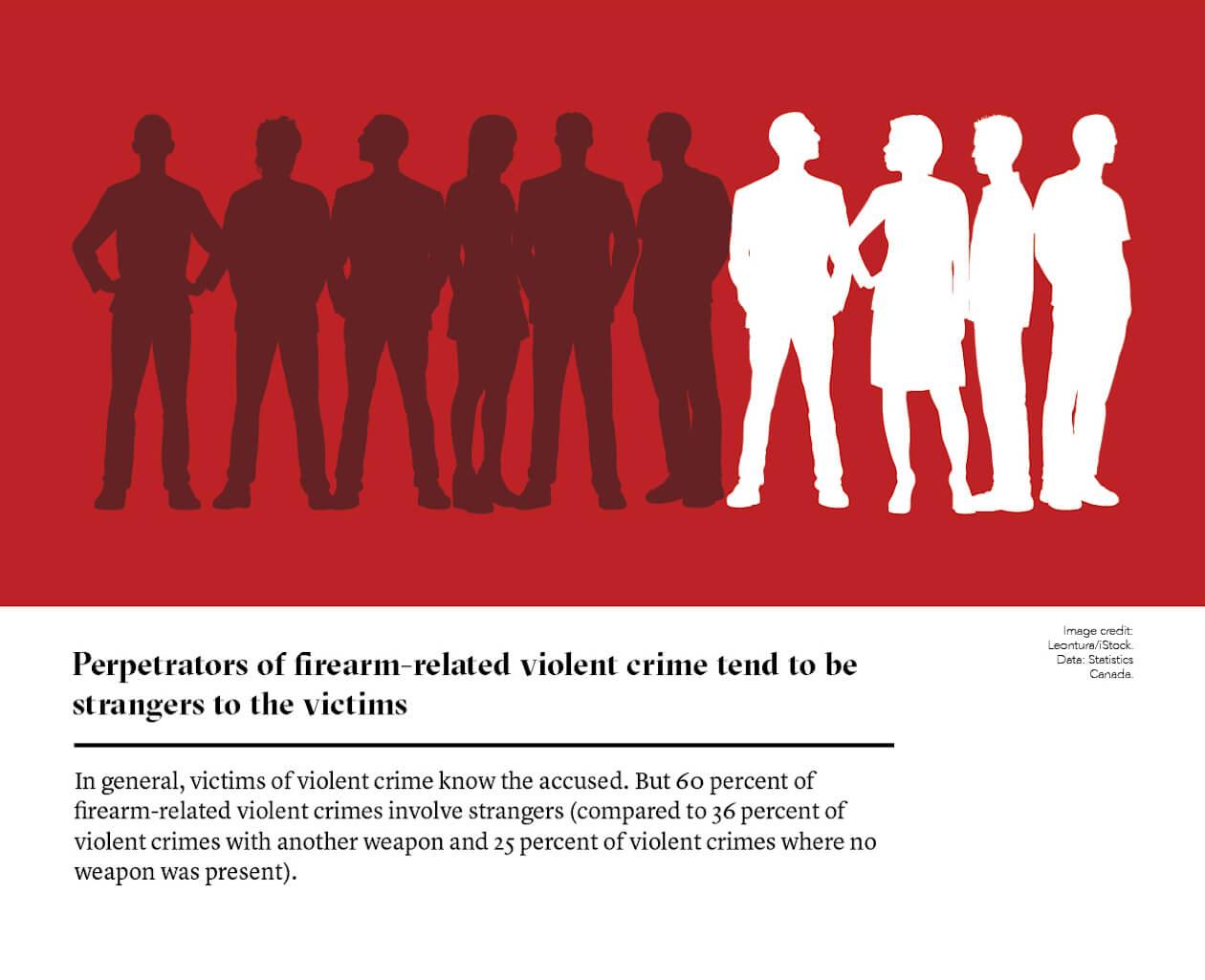

But Canadian gun-related crime isn’t limited to urban gangs. In fact, excluding the US, which is a dramatic outlier in all such comparisons, Canada has some of the highest firearm-related homicide and suicide rates in the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, an intergovernmental economic organization with thirty-four member countries, including Mexico, Germany, and the UK. Meanwhile, our rate of firearm-related crimes grew faster than any other category of violent crime between 2006 and 2016. (After peaking in the mid-1970s, however, the national rate of gun-related homicides has generally been in decline, according to a Stats Canada report from 2012.)

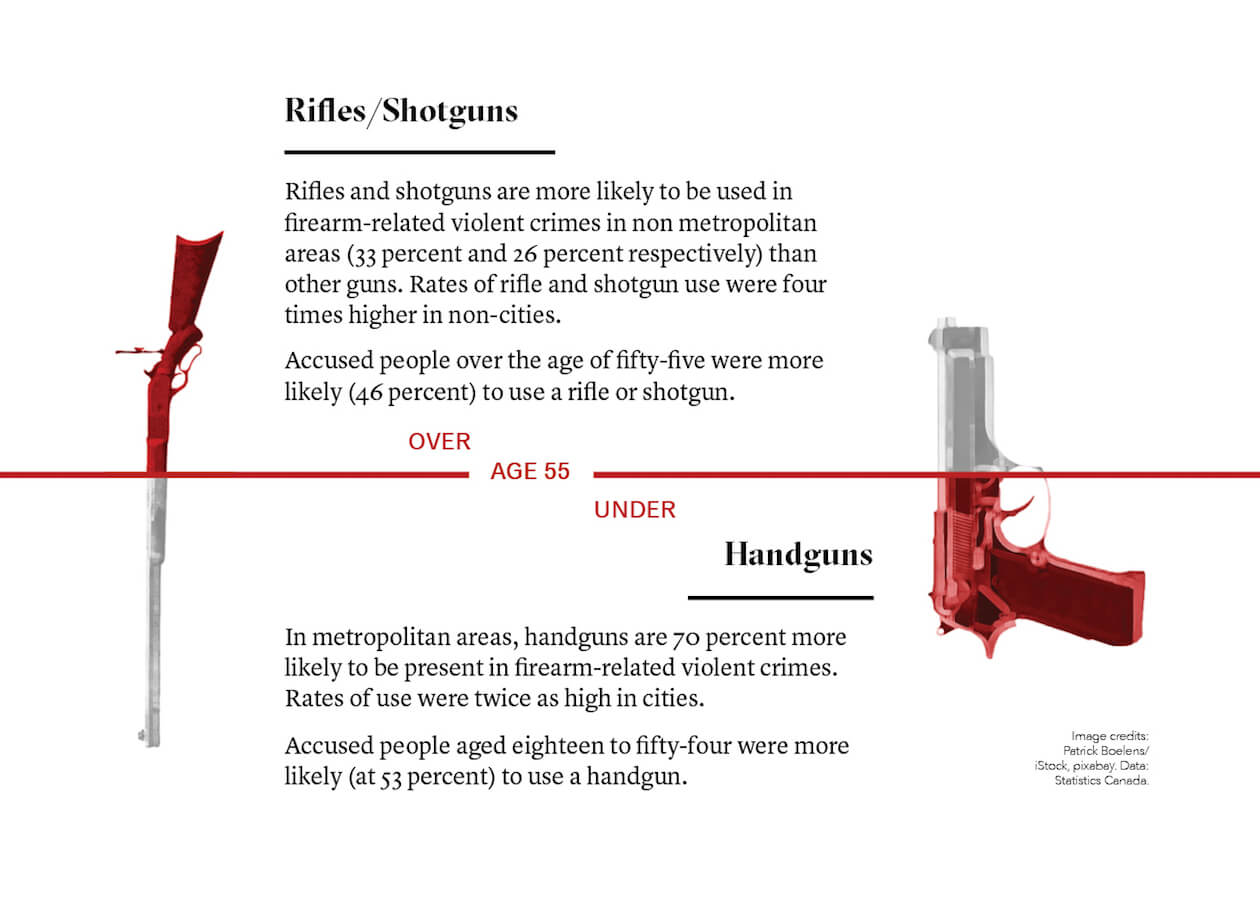

The long-gun registry focused on “non-restricted” firearms, such as the one Lépine used. It was also widely praised for—among other things—its role in helping police respond to domestic-violence calls and suicide prevention. If one took the rhetoric of the Conservatives and the gun/hunting lobby at face value, these long guns were primarily the sorts of rifles and shotguns that would be used for sport shooting or other similar applications, especially in rural areas. These sorts of guns, goes the argument, pose no safety risk because would-be criminals wouldn’t, presumably, make the effort to register in the first place.

Nothing could be further from the truth. A scan of the offerings of Firearms Outlet Canada, an online gun shop with a retail location in Ajax, Ontario, and one of many such dealers, reveals that “non-restricted” firearms include all manner of fearsome military-grade weaponry. These include semi-automatic rifles, such as the Kriss Vector Gen II CRB Enhanced, a gun which, according to the website, complies with “the 21st century requirements for the global law enforcement, military and civilian markets,” as well as the X-95 Flat Dark Earth IWI, which was developed “in close cooperation with the elite units of the Israeli Defense Forces.” The X-95 is not cheap ($2,700), but prospective buyers need not fret about a surfeit of regulation, and the dealer ships the product using Canada Post. As the page for these weapons dutifully notes, “This is a Non-Restricted Firearm.”

While bump stock, an add-on that greatly increases the speed with which a semi-automatic can fire, is not on offer at this retailer (it is not permitted in Canada), there are entire pages dedicated just to the hundreds of “non-restricted” long guns. Providing they have the licences to acquire it legally, customers can also choose to purchase restricted firearms, including the Tokarev TT33, the $300 semi-automatic Soviet pistol with which Saskatchewan farmer Gerald Stanley fatally shot Colten Boushie, an unarmed Indigenous man. (Stanley was later found not guilty of second-degree murder; he said the gun fired by accident.) Or a person might purchase a non-restricted firearm, such as the Kodiak Defense CZ 858, the semi-automatic rifle Alexandre Bissonnette is reported to have had in his possession when he allegedly shot six worshippers in a Quebec City mosque last year.

In short, there’s clearly a robust market for legal firearms in Canada, and some of those guns end up killing people. Beyond that, the number of registered restricted and prohibited firearms leaped slightly more than 20 percent between 2013 and 2016, from just under 850,000 to more than 1 million. In 2016, moreover, Canadian law enforcement officials recorded over 15,000 weapons violations. The jump indicates that the number of weapons in private hands is growing, but it also suggests that many owners do comply with gun-control regulations and register their firearms.

Is there a relationship between the growth of gun ownership and the growth of gun-related crime? Yes, some of the firearms used in crimes, especially in urban areas, are smuggled handguns that come up to Canada in the panels of car doors. But if we can wag our fingers at American conservatives who balk at any suggestion of a causal relationship between the proliferation of guns and mass shootings, we should certainly be prepared to admit as much here.

Besides mere partisan calculation, this position seems increasingly indefensible. The registry, as Canadian police chiefs have repeatedly said, helped them fight gun crime. Quebecers have agreed to adopt their own new registration rules with barely a grumble. Canadians, in turn, own a growing number of guns. And by the government’s admission, the number of firearm-related crimes has been rising, quite steeply, in recent years. What could the Liberals possibly be waiting for?