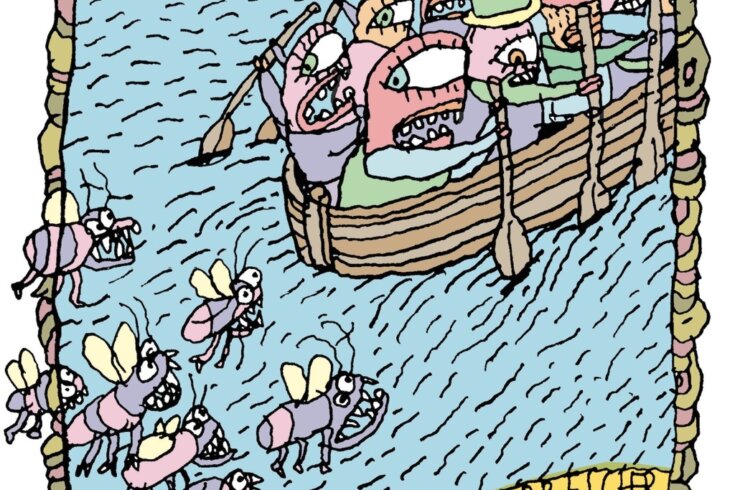

The scene is a large field with a stage and tents near Kearney, Ontario, close to dusk. Billions and billions of blackflies have gathered for BloodFest “06, the annual rally for the 255 North American species of the blood-feeding family of Simuliidae. One of their leaders, Eric, hovers up on stage. Like all blackflies, he is humpbacked and bug-eyed. He wears a BloodFest “06 T-shirt with a squashed-mosquito icon on the front and the slogan “You suck—I bite!”

“Greetings, Simuliidae! [The insects cheer and swarm.] Welcome to our annual rally, close to the all-you-can-eat blood buffet of Algonquin Park. My name is Eric and I’ll be your host this weekend, so just relax and enjoy. [They hover.] I guess you all know why we’re here today—to celebrate the blackfly’s contribution to Canadian history and ecology, to learn more about our neglected heritage—and, of course, to knock back a whole lot of blood! [Whistles.] Have you checked out the park yet Man, I bit one tasty loon today. [Someone fakes a loon call.]

“Speaking of loons, I have to ask: how come they end up on a coin and we don’t Is it the bling around the neck Loons can vocalize, no question, and they’re crazy enough to mate for life [guffaws]…but they don’t kick butt like us!

“And did you see all those TV ads during the Olympics, with those two cartoon beavers How do they get to be a Canadian symbol We are talking about a large, nocturnal rodent with tiny eyes, folks. Okay, they have good work habits—beavers are the cubicle workers of the animal kingdom. But they destroy trees. Is that what we want from an icon They dam the rivers we depend on for our hatching and incubation, and they’re hopeless in a crisis. For instance, if Canada requires more military muscle—say in Afghanistan—what good is a beaver Are they going to make checkpoints out of twigs and mud Our mighty nation of blackflies, on the other hand, can marshal aggressive bug power up into the trillions. The human politicians Stephen Harper and Rick Hillier claim they want to strengthen our military presence. Well, we have the numbers. We trump the Canadian population by at least a couple billion. And we’re aggressive—we’re the ultimate carbon-dioxide-seeking missile. Consider what a Blackfly Battalion could do to safeguard international peace. [Some insects start chanting “All we are saying…” until the rest drown them out.]

“By the way, has anyone out there ever tried to bite Stephen Harper Tried to get up into that gelpak hairline I haven’t worked so hard since I tried to feed on a prairie bison. He was worth it, though. There’s really nothing like human blood, right [Cheers.] But our impact on animals has been totally underestimated; do you really think those herds of caribou in the far north migrate just for the fun of it No! They’re trying to outrun us! Self-esteem, folks—just remember that a couple hundred blackflies in a feeding frenzy can bring a 300-pound ungulate to its knees. We may be small—okay, we’re tiny, and we only live three weeks—but were powerful. No one, not even Donald Rumsfeld, has considered harnessing the power of the blackfly as a biological weapon. But when the call comes, we’ll be ready! [Sustained applause.]

“Hey, remember when Justin Trudeau took that little paddle down the Nahanni Wasn’t he delicious See, we don’t discriminate between who we bite and who we don’t—and that’s what you want in a fighting insect.

“A word about mosquitoes here. [Boos.] No, come on now, they do what they do pretty well. I know some of you think they’re just stagnant-water bums who can’t hack the currents, but with the heat on about West Nile these days, theyre going through a rough time. deet levels are up everywhere—I don’t have to tell you that. They’ve lost a lot of numbers so let’s remember: we’re all insects here. Although they tend to overdo the whining thing, and their tactics are predictable—buzz, land, eat sort of thing. Bo-ring. A lot of them get whacked that way.

“But when a human encounters a blackfly…well, we’re just very erratic. We hover. We crawl, but we don’t always bite—it drives the humans nuts! We can also land silently, infiltrate cuffs and collars, scope out the rim of the ear—yum—then we open our mouthparts and actually bite their flesh! That little pool of blood is what nourishes our eggs, of course. But it’s not even strictly necessary—we just like to do it! By the time the humans get around to slapping at us and counting their welts, we’re already out of there, with their blood. You know, there’s nothing wrong with mosquitoes for simple puncture wounds and all-round irritation. It’s just that in terms of numbers and stealthy aggression, we’ve got it all over them.

“But listen, isn’t it weird that May 24th is the weekend when many humans leave home to visit their small woodland dwellings What are they thinking This is our time! The rivers thaw, the tree buds burstand were all out there, on the job. Just the other day, I personally fed on the blood of every member of the extended Patterson family of Gravenhurst, Ontario, who were determined to grill some steaks, at dusk—near some rapids. [Laughter.] There was some serious football neck there, folks—tough but sweet. Ten minutes, and they were running back inside. On May 24th—we rule! [Whistles, swarm-dancing.]

“A couple announcements: for all you ladies, the prenatal tent is set up in Section H. I know some of you are laying 150 to 600 eggs a season, and we want you to know that we really appreciate all your efforts. [Applause.] After all, not only do you lay all the eggs, you do all the biting and feeding to fatten up the eggs.” [” And what is it you guys do again” Laughter.] “Okay. Nice. Settle down, ladies.” [Male voice shouts, “We have sex with blueberries.”]

“Suuurre we pollinate the berries—who started that rumour anyway We might hang around blueberries. We might land on them or skim off a little nectar, right But we leave the pollinating to the big furry guys who buzz. No, our job is…[He turns to a roadie standing in the wings.] Can you help me out, Richie

“That’s right! Our job is to hover and to crawl.”

[The crowd whistles and makes circular hovering gestures with their legs.]“I know you’ve been waiting all day for the trivia quiz, and here’s a little teaser: I’m looking for a line from an Alanis Morissette song. It’s supposed to be ironic: That would be…”

“A blackfly in your Chardonnay!”

“You got it. It’s like ray-ee-ain on your wedding day Alanis, that is not ironic, that is just an unfortunate turn of events—even an insect knows that.

“Hey, the Nunavut Giganteums are with us, over there, and I see the Labrador blackflies have just arrived—welcome to Ontario, you crazy bugs. I hear you’re brutal even in July. You know how one canoeist described the Labrador blackflies—he called you “vicious, carnivorous, little flying piranhas!’ My question to him: Do you need to canoe in Labrador Are you Jacques Cartier

“But seriously—it’s great to have so many larvae with us today. Moms, we’ve set up a flume ride for them over in the corner. You little guys are one of the most efficient filter feeders in the water world, did you know that You get 800,000, a million larvae in a fast-running river, all feeding on microscopic organic matter, and they turn into a great little food factory for everybody else in the water. Did you know that the fecal pellets of blackfly larvae retain 80 percent of their nutritional value [Whistles and cheers.] People think our whole thing is biting and bloodfeeding…”

“And hovering!”

“And hovering. But the fact is that were a major player in the ecosystem—because wherever you find blackflies, you’ve found clean running water. Humans are finally starting to recognize this, and I’m happy to say that we have one of them here with us today. Can you stand up, Professor Doug Currie. [A lone human in a bug hat and hazard suit, engulfed in a black cloud of flies, stands up.] Professor Currie has devoted his professional life to the study of blackflieshes one of the world authorities on us—and he is of the opinion that we get a bad rap. Mr. Currie is curator of entomology with the Royal Ontario Museum’s Department of Natural History, a professor in the Department of Zoology at the University of Toronto, and he has published numerous articles on us. Come on up here, Doug.” [He steps out of his suit and goes on stage wearing only a bug hat. The microphone feeds back a little. He is nervous.]

“Hello Is this on Hi.” [He lifts the bug veil.] “Can I take this off [Eric pretends to dive at his neck and everyone laughs. Currie drapes the veil back over his Tilley hat.]

“Thank you very much for inviting me to BloodFest “06. It’s a real honour to be here. As some of you know, I’ve been studying the blackfly for many years. I’ve canoed the Thelon and paddled 700 kilometres down the Horton River in the Northwest Territories, just to figure out what makes you tick—if youll pardon the term. [Laughter.] People sometimes ask me, why blackflies Why not butterflies or no-see-ums I’m not sure. I know I find the white-stocking blackfly a rather pretty insect [whistles] with those white markings on the legs. But there’s so much about your species that I admire—your tenacity, for one thing. Not every bug has been around since Jurassic times. And your diversity—over 1,200 known Simuliidae species in the world. And I can’t get over your immature stages, either. How many larvae, for instance, could figure out how to stick to a rock at the lip of a waterfall”

“I don’t want to get you nervous, Professor Currie—just because there’s a field full of us out there—but I guess youve had a few welts in the line of duty. Tell us about the bites.”

“Well, on the Horton we encountered a herd of Bluenose caribou that were crossing the river at quite a clip. They were followed by this great black plume of pestilence, until the blackflies noticed us and went after us instead—we were slower. [Knowing cackles from the crowd.] To me, being bitten is just part of being out there. Actually, I think you guys help protect the entire Arctic region from being overrun by tourists who just don’t want to put up with the bugs. But clouds of biting insects are part of our heritage. [Some applause.] It can’t all be about sunsets and scenery.”

“That’s right. Were not just a postcard of Lake Louise—we’re also a country rich in blood-feeding insects! [A hovering ovation.] And I think that’s an appropriate introduction for our next speaker, Victoria, a blackfly historian from the Yukon.” [A blackfly indistinguishable from any other blackfly takes the stage. She has a tic in one wing and carries a sheaf of notes.]

“Thank you Eric and Professor Currie. Im so excited to be here at BloodFest because this is a chance to correct a lingering injustice in our history. [Some larvae are bouncing a giant ball around the crowd. Victoria looks annoyed.] If… [The ball hits her.] Do you mind [The crowd settles.] Thank you. If you study pioneer literature and the journals of early explorers, you will discover a very disturbing thing: we don’t exist. Most of the time, nobody bothers to distinguish us from mosquitoes, and often we are simply referred to as “bugs’ or “insects.’ Here is a quote from Samuel Hearne’s Hudson’s Bay journals, in the year 1775. He is trying to blame the construction delays at Cumberland House on the “mosquitoes.’ [She reads.] “The reason of our not getting a sufficient quantity of Plank cut emediatly on our arrival ware oweing to the Meskittas being so thick that the People could not work in the woods.’ Obviously, there were some mosquitoes involved here. But who does that sound like”

“Us!”

“And why do you think the voyageurs paddled fifty strokes a minute, for fourteen hours a day Out of diligence or duty No. They set a breakneck pace because if they stopped paddling, the bugs would blacken their bacon and coat the coffee in their pot. It’s possible that Canada today might not extend beyond Thunder Bay if the bugs hadn’t been driving the early explorers ever westward. The very shape of our country might have been the result of men desperate to exit the wilderness.

“Listen to this testimonial from the early 1900s naturalist and author Ernest Thompson Seton: “The blackflies attack us like some awful pestilence walking in darkness, crawling in and forcing themselves under our clothing, stinging and poisoning as they go.’ Contemporary author Margaret Atwood, whose father was an entomologist, frequently alludes to birds, snakes, and mosquitoes in her writing. But she has publicly confessed that she considers the word “blackfly” a mere localism. When Ms. Atwood spoke to a British audience for her 1991 Clarendon Lectures at Oxford on the subject of the strangeness of the Canadian North, this is what she said: “I will try to avoid using specialized vocabulary, such as “toe rubbers’, “blackfly,’ and “chinook’, without clarification.’ How tragic that she overlooked this unique opportunity to carry the blackfly name and reputation overseas.” [Scattered applause as Victoria leaves the stage.]

“Thank you, Victoria, for those insights. Now, for our final guest appearance, I need your attention and respect. As some of you know, some years ago, as an ironic tourist incentive, the town of South River in Ontario launched an event known as the Black Fly Hunt. [Some boos.] Hang on, let me finish. This event involves a four-week competition to see who can capture the highest number of blackflies. The 2005 winner, Roy Warriner of Trout Creek, Ontario, has admitted that he used a net to capture 3,213 of us, in the Almaguin Highlands. [The crowd falls silent.]

“Now, in the big picture that’s not a lot, but we lost some key players: Sabrina from Rainy Lake, Trudy from Powassan. These courageous insects were just doing their job when they were netted (and eventually died). I know humans have to protect their species, who cannot fly and who depend on Weber barbecues and motorized watercraft for their well-being. But Roy Warriner was a merciless bounty hunter. [He shows a picture of Warriner being crowned World Blackfly Hunting Champion.] Please, if you see this human, fly away quickly. According to our intelligence, he wears pants with a button-fly; in the event of an encounter, you can infiltrate in that region.

“Okay, I know everyone is eager to get at the all-species buffet, so I just want to leave you with a few empowering thoughts: Would the Arctic be overrun by pina-colada-slurping tourists driving atvs if we weren’t working overtime to drink the blood of every innocent two-legged visitor Would our national parks buckle under the influx of unharrassed human beings We’ve got a stake in this great country of ours and it’s time we were recognized for the work we do—keeping the wilderness wild, and the rivers full of life.

“Remember: we don’t suck…”

“We bite!”

[The Rolling Stones’ “Let It Bleed” plays over the sound system as black swarms settle on picnic tables.]