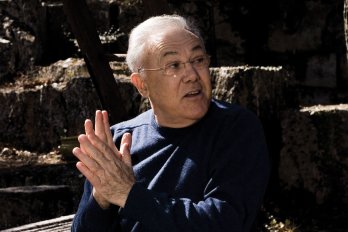

Mission — “Here I have lived and here I shall die,” he said. Behind him, rain drummed on the window and treetops bent with the wind. “Yes, I will be buried here and another will come to take my place.” I could detect no sorrow or fear in what the old monk was saying. He himself was not the point. That others should come, that this order to which he had devoted his life should endure—that was of primary importance. His smile was warm, the look in his eyes confident.

The phone rang and Father Basil excused himself. “Pesky things, aren’t they?” he murmured as he shuffled off. Even here at Westminster Abbey, sixty-five kilometres from Vancouver, technology made its claims on life. While the Father was gone, I checked the time. Had the bells rung to mark the hours. One hour after the next—I had had no intention of staying this long. I had been basking in what seemed to me a realm of Being, my mind and limbs at ease. Outside, the world was busy Becoming, and I would soon have to return to making of the chaos what I and only I could.

Father Basil returned and sat down on the window ledge across from me. He folded his large hands into his black habit, looked to me and said, “So where were we?”

How does a young man say to an old monk, “We were at the point of your death, Father” I fumbled and searched and finally came up with “Continuity. The future of the Benedictine order. Will there be enough young friars to take the place of the old?” He looked at me quizzically, his blue eyes perched above the rims of his glasses. The Father is a grammar teacher in the seminary and has a deep affection for words. “Friars! Friars There are no friars here, me boy,” he said. “You must have read Robin Hood when you were a child. No rotund, staff-wielding, mead-drinking friars at this abbey. The brothers and I live by the Rule of St. Benedict. We are civilized—we drink wine!” He chuckled. Monks from this order used to make Benedictine liqueur but “during one war or another the recipe was stolen and never returned.”

Fortunately, there was still tobacco. The Father partakes of a bowl each night at 8:30 and had been overjoyed by my donation. “Splendid! I had put out word for some English Mixture,” he’d said when I produced the pouch, apparently joining the network of patrons who keep him in smoke.

“Now back to your question. Yes, our ranks will be replenished,” he said. “In fact, the order is experiencing a revival of sorts.” The Benedictines are now recruiting in Asian communities, for example, where interest in monastic life is high.

Over half a century ago, Father Basil helped dig this monastery’s foundation. He was a young seminarian then. “It was the writing of Father Merton that really opened me up to the monastic life,” he said, referring to the Trappist monk Thomas Merton, author of The Seven Storey Mountain. “Young Catholic guys like me were fired up by the challenges that Father Merton proposed: the devotion, the sacrifice, the hard life.” But not too fired up. “There was no way that I was going to go down to Kentucky to join the Trappists. I wasn’t crazy! Those monks lived on nothing but bread!”

Asceticism is among the many constants of monastic life. Benedictine monks like Father Basil, however, though bound by vows of obedience, stability, and “conversion of life” (which implies poverty and chastity, among other ideals), feel that the odd glass of wine or bowl of tobacco need not impede their progress toward union with the Lord. The Rule of St. Benedict is central to their journey. This has been so for over 1,500 years. The Rule is a thread that has been spun out of Monte Cassino, in the hills of central Italy, into the most enduring form of monasticism in Western religion.

The phone rang again, and this time I had to alert the Father to the fact. Outside, the wind continued to blow. Father Basil reappeared with some photographs in hand. The first was a black-and-white of a young man walking alongside a young woman. He was square-shouldered and handsome, she slender and pretty. “This girl is Molly, whom I was telling you about,” he said. Ah, Molly. They had been in love and then parted. She went to a convent to become a nun; he came here. He stayed; she left—both convent and faith—moved to Oregon, got married, and had kids.

The next photograph was recent, and I recognized the surroundings and the man. He was dressed in a blue polo shirt and his arm was around a woman. “That’s Molly now,” said the Father. “And that was Molly on the phone. She comes to see me now and then. Her faith has been restored.” This brought the Father great happiness. It seemed that Molly had never left his heart.

“Next time I will play the organ for you,” whispered Father Basil after leading me into Westminster Abbey’s church. He rolled back the cover from the keys. Brother Peter had restored this organ using ivory from an old elephant tusk. Across from us, a young monk was praying—oblivious, it seemed, to our presence. Elsewhere on the grounds, thirty-two other monks were fulfilling their tasks, from tending livestock to updating websites. Looking down the nave at the stone altar, I realized that if the power were cut, things would be much the same here as they had been ages ago in Monte Cassino. These men would still live under the same Rule and take part in the same daily routine. They would be serving the same Lord and seeking the same reward. This was Being from floor to ceiling, and there was something very comforting in it. If only Becoming weren’t so damn tempting.