The horrific spread of aids in Africa has led some to call it “the orphaned continent.” South Africa alone has six million infected men, women, and children, with invisible millions already buried. Surrounded by South Africa, landlocked physically and spiritually, sits the small state of Lesotho, where, in December 2004, Canadian doctor Philip Berger arrived for World aids Day. At the behest of United Nations Special Envoy for hiv/ aids in Africa Stephen Lewis, and as part of a special program established by the Ontario Hospital Association, Berger spent seven months in Lesotho at an aids clinic. By his own account, Lesotho—population 1.9 million; 300,000 adults and 20,000 children infected with the aids virus; 29,000 aids-related deaths per year—is dying. Short on medicine and staff, Berger persevered as best he could, and at night sent emails home. The following text is a small sampling.

December 1, 2004

Hello everybody.

I apologize for a ghastly mass communication but life is very complicated in Lesotho and efficiency in email contact is paramount. Nonetheless my email problems are trivial next to the devastation endured by the Basotho, the people living in Lesotho. Lesotho has an hiv prevalence rate among adults of almost 30 percent. One hundred thousand children have lost at least one parent to aids. One of the hiv counsellors at the Motebang Hospital where I will be working knows of no family that has been spared an aids death. The Motebang hiv clinic is called Tsepong Clinic, which translates as “Place of Hope.”

December 4, 2004

Yesterday we visited the Senkatana Centre, an antiretroviral hiv/aids clinic that opened in May 2004. The name Senkatana derives from a Lesotho legend. Some time ago a terrible monster devoured all the people and animals of Lesotho except for a lone pregnant woman who eventually gave birth to a boy named Senkatana. When he grew older Senkatana asked his mother why there were no people in Lesotho and she told him the story of the monster. So Senkatana armed himself with a spear and slayed the dragon, freeing all the people and animals of Lesotho. Here, hiv is the monster and the clinic is Senkatana.

December 12, 2004

It’s six o’clock on Friday night, December 10—International Human Rights Day. A Motebang Hospital pharmacist just left our home. She came here especially to inform us that there was no infant antiretroviral syrup available or obtainable for a four-month-old girl who we admitted the day before. The girl weighed three kilograms, her eyelids weighed down by exhaustion, starvation, and dehydration, both elbows flexed and held tightly to her sides, fists in an atavistic clench, legs not moving, thigh skin sagging and geriatric. A local aids MD exclaimed that, “This little thing is not enjoying life at all.” The infant girl is so dry that no veins are accessible so the doctor inserts a needle into the child’s groin, apologizing as she plunges it in. The girl speaks for the first time, letting out a hoarse, frail, failed whimpering wail, not the piercing cry of a healthy child.

I am weary and it is late. Of the thirty people we have seen [today] twenty-six were women and children. Staff here dread the Xmas season when male migrant mine-workers return home to their already infected wives and reinfect them, the wives defenceless, terrified of disclosing their condition until the wasting does it for them.

December 22, 2004

As we began our morning clinic, a forty-year-old man was carried in by his brother and friend. They propped the man on a bench beside the others, trying to keep him sitting up . . . not for long. The man suddenly slid down to the floor and stopped breathing, died in the waiting room. No screaming or panic here. We carried him into the nearby meeting room where we confirmed his death before brother and friend . . . no resuscitation equipment at the clinic, no protest, just a slowly forming apologetic tear in the corner of the friend’s eye. The patient lay sprawled on his back, fully dressed, legs in open scissors formation, arms slightly outstretched . . . he looked like he had been slain in an old-fashioned gun duel. In Canadian emergency situations he likely would have had his clothes torn off as revival efforts were instituted. His brother tried and failed to do what the nurses normally do at Motebang Hospital, dislocate the temporomandibular joints so that the teeth of the dead do not protrude . . . because the clinic does not have nurses.

Today we were told that only four bottles of a combination arv were in stock and, at our current pace of prescribing, the supply would be done by next week. An hiv treatment interruption—even by hours—can lead to viral resistance and end the capacity of drugs to beat the virus, not only for the individual whose continuity of arvs is broken but beyond, filtering through to sexual contacts newly infected with now-drug-resistant hiv.

January 2, 2005

Never-ending conversations about “sustainability, empowerment, capacity, rollouts” by “expats” (I guess that includes me) who are “in country” . . . I don’t know what any of these terms really mean . . . what does “in country” mean? I disdain censorship but figure it would still be a good idea to ban all these slogans and start all over, forcing an exact enunciation of what people really think without the cover of inexact jargon.

January 5, 2005

Some signs of victorious battles . . . twenty-nine-year-old woman, 46.5 kg , cd4* count of 411 (almost normal) and a hemoglobin† of 9.4 (normal is 12 but this is great for here); my colleague Dr. Bob Birnbaum exclaims “she is rocking” and so she is. Saw in follow-up a twenty-seven-year-old woman who we treated for a presumptive pcp‡ on Dec. 22, then gasping at 48 breaths/minute with an exercise-class pulse of 144/min—now breathing at 16/min and pulse at 108/min. Her hemoglobin, at 7.7, will always give her a fast pulse but as she says, “I can breathe.”

*cd4—The immune system’s critical cells that hiv attacks

†Hemoglobin—Oxygen-carrying molecules of our bodies

‡pcp—Killer aids pneumonia

January 9, 2005

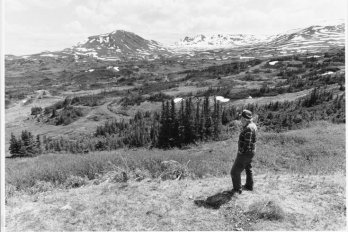

While climbing the 180-metre mountain behind my house this a.m. with Bob and Russell, passing rondavals, gardens, massive aloe trees, cattle in pasture, brick huts, roofs held down by rocks, always greeted by smiles, hellos and some giggles, guided at times by young barefoot boys to the safest path, we were discussing hiv resistance. Bob said if the arvs are not available this week it means resistance, and I agreed it would be disaster for Lesotho and he said “No, resistance for the world.” He is right. Then horrible thoughts came . . . so what, Lesotho dies with aids and without arvs and without resistance, or it dies with aids and with an interrupted supply of arvs and no infrastructure and arv resistance. So what? Matters not to a fifteen-to-forty-nine-year-old generation who will fade away anyway. hiv and hiv resistance could be halted if hiv was engaged as war is engaged. In the meantime Lesotho and the patients we see have nothing to lose, may even gain a few years (which is a lot here and they know it).

January 30, 2005

Last Sunday the church bells announcing the end of mass were delayed. The senior priest delivered a forty-five-minute sermon about the Hope Clinic, the need for early testing, the signs and symptoms of aids, the Christian requirement to battle aids discrimination…to 500 congregants. The Roman Catholic Church is the dominant Christian denomination in Lesotho, its influence is powerful. The bishop of Lesotho publicly underwent hiv testing. The RC Church is central to protecting the weathered women with aids, and paving a path of safety to arvs through the mothers—a gateway for their children before they starve to death in the pediatric ward of the hospital. Monday’s clinic was busy, congregants in attendance.

February 17, 2005

Baby girl, face irresistible, sagging safely into her maternal grandmother’s lap. Mother died of aids in November 2004. Personal health record tells all. An oha team member [TM] takes over through an interpreter.

TM: “Does grandmother know why mother of child died?”

Grandmother [GM]: “She went for many consultations and got here.”

TM: “What did she die of ?”

GM: “She had nervous system problems and coughed a lot.”

TM to me: “She is refusing to name the disease.”

TM to interpreter: “Like it or loathe it, tell her that baby has the same problem as the mother.” He tells her.

GM: “Ohhhh.” Drawn out in typical Basotho exclamatory manner.

TM: “Does she see that herself?”

GM: “I have been noticing the similarities myself.”

TM: “We are going to try and help to make the baby not suffer too much.”

GM: “Ohhhh.”

TM: “But she must understand that this is painful for doctor and me because we know that we cannot cure baby.”

GM: “Ohhh, Ohhh.”

February 26, 2005

Saw a boy, born December 6, 1995, introduced to the clinic a few months ago. We breached international standards by breaking arv tablets in half to produce as closely as possible a childhood dose (prohibited in Lesotho and elsewhere and denounced by increasingly distant experts—see New York Times Feb. 22 editorial) and giving them to the boy whose only other option was disappearing “over there.” Baseline weight at first visit was 19.3 kg, and this week, after a month of arvs, he weighed in at 22 kg—a 14-percent increase. His grandmother reported that he could somersault. We walked to uncut grass just beyond the clinic entrance. He jumped ahead and to cheers of nearby patients rolled through an acrobatic somersault, merging into a sustained headstand; unflinching, straight up and steady. New pediatric test invoked at Hope Clinic: the “somersault/handstand” test.

March 25, 2005

Morning clinic initiated with regular hymn and prayer. All rose except blanket-enveloped man, head toque-covered and body tilted over left side of a wheelchair. I asked a local counsellor how the ordinary Basotho can sing with such perfection and fullness of heart. She replied: “We’re born to sing. We just do it.” Here is what the dying sang in Tuesday’s hymn:

“We praise you G-d

We are happy for you

We’re living happily under your protection

Right now your children are helpful to other people

Through your mercy we’ve been delivered from evil.”

The ailing Basotho all cross themselves.

April 18, 2005

Have ceased taking detailed notes on the humans entering the gated doorway of the clinic . . . no purpose and tales redundant. But the surrealistic settings take hold in one’s mind without need for recording weights, cd4 counts, or respiratory rates. Though penultimate gasps always impel a retreat into counts of breaths per minute, extreme wasting demands a weight, if only for affirmation of what seems unacceptable and unbelievable.

My Peace Corps friend Elliott Friedlander completed a tedious aphorism I once threw in his direction. I told him that “There are no secrets in Lesotho.” The always and sometimes frighteningly on cue Elliott added: “. . . and no secrets leave Lesotho.”

— Philip

Steve Simon is a Canadian freelance photographer based in New York City. He has documented the spread of HIV in Zambia, Mozambique, Ethiopia, and Lesotho. Simon’s work has appeared in Harper’s, German Geo, and the New York Times Magazine.