IN THE FULHAM ROAD

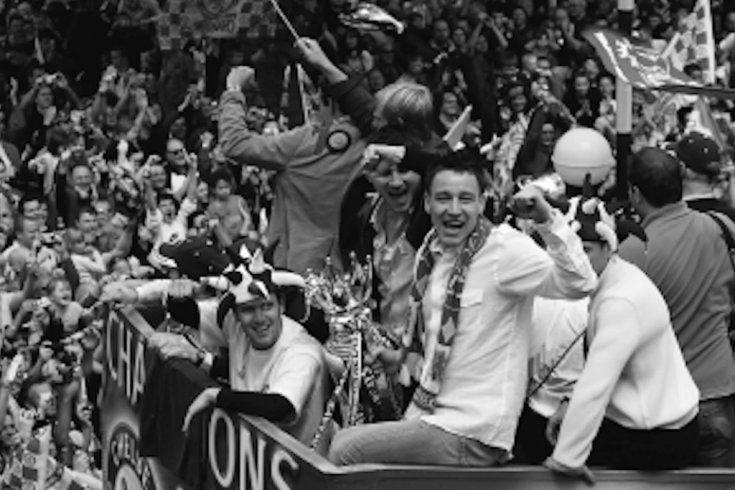

This crowd is unlike any I’ve seen before. Maybe 10,000 people, Chelsea Football Club supporters. Far fewer than were inside Stamford Bridge Stadium a moment ago when the final whistle blew, but I’ve never seen more human beings per unit of pavement. I’m moving without any control over my direction. Bodies are wedged against me on all sides. And they’re singing. In one booming voice, to the tune of “For He’s A Jolly Good Fellow”:

And now you’re going to believe us,

And now you’re going to believe us.

And now you’re going to believe u-uuuuussss . . .

We’re going to win the league!

The hairs on the nape of my neck are standing up. A strange feeling sweeping through. Hyperreality: an experience inexplicable without reference to the television version known previously. Because I’ve heard football songs before. I’ve joined the Chelsea crowds many times via broadcast signals ghosted off satellites in geostationary orbit in the exosphere overhead. I’ve felt the connection. At least I thought I had until I entered this narrow surge channel passing from the West Stand up onto Fulham Road and encountered the passionate, on-the-ground reality of team devotion.

Now my mobile is ringing and I struggle to get it out. It’s my London-based friend, Sean, shouting to be heard: “We’re in the pub across the road.”

“I can’t cross. I can’t change direction. I’m being swept along here.”

“Cut left, cut left. I can see you. I’m waving my arm now. I’m waving my arm!”

No saying excuse me. Working this human river takes shoulders and arms. You have to slide and roll, pick your spots. I’m carried sixty feet before I escape to the wall, where I work my way back to the pub door. But even inside, upstairs, beer in hand, I can’t take my eyes from the streets below. A tide of blue and white, a celebrating sea of song, all the more impressive knowing Chelsea didn’t even win tonight.

A nil-nil draw. That was the result I travelled 7,600 kilometres to see. Chelsea at home against crosstown rivals Arsenal, the Premier League defending champions and a team Chelsea hasn’t beaten in league play for an agonizing ten years. But even without a win, Chelsea is eleven points clear in first place with just four games remaining in the season. And on the street below, the fans of a club that last won the league when Winston Churchill was in Downing Street know that the curse is over.

Now the Arsenal supporters are leaving Stamford Bridge, their coaches inching from behind the East Stand toward Fulham Road. And everybody below and in the room around me bursts again into song. Sean’s friends too, who, like me, aren’t your typical English “footy” supporters. No beer guts, replica jerseys, Burberry ball caps, or gold chains. These are educated, new-economy types. City financiers, an aromatherapy products entrepreneur, an Eton-educated son of money who runs an organic farm north of the city. But even they lean out the windows and shout the refrain down to their departing rivals:

We’re going to win the league!

We’re going to win the league!

“Well,” says David, an investment fund manager, smiling slyly at my elbow. “What do you make of all this?”

I can only shake my head. But what I’m thinking is that it looks very much like what the local press started calling it shortly after Chelsea was purchased by Russian billionaire Roman Abramovich two years ago. It looks like The New Roman Empire, a force that will upend the prior order of things, that will accomplish precisely the objectives of this revolutionized football club: quite simply to become the biggest, most successful in the world, to be known in your neighbourhood, wherever you happen to live.

THE CHELSEA REVOLUTION

I am part of a visible phenomenon at Stamford Bridge these days: the football tourist. Those guys drinking down at the end of the Shed Bar? Norwegians. The people spilling out of the coach that just pulled into the yard? Chinese. The fan clubs from New York and Iceland are both reportedly here. Local fans, I learn with each conversation, are bemused.

“It’s been fifty years since we won the league,” said the man in the seat next to me during that Arsenal match. “Do you have any idea what that means? We’ve been waiting fifty years.”

No, I don’t have any idea. There were no blue-and-white scarves hanging from the coat rack in my West Vancouver boyhood home. My allegiance to Chelsea is a perfectly North American construct: an arbitrary, although inspired, whim. Specifically, a sporting fever picked up watching a five-and-a-half-foot-tall striker named Gianfranco Zola who could tuck free kicks into top corners with a dexterity that took the breath away. “The Little Sardinian” joined Chelsea in 1996, and, after a few years watching him on television skim uprights inches beyond the keeper’s reach and bend wicked shots around walls he couldn’t even see over, I was hooked.

As were many others. Chelsea is located in famous, fashionable West London. Think Chelsea boots, green mohawks, skinhead chic, Sloane Rangers. The place is hard-wired into the global cultural grid, and that’s probably why I’ve run into more remote Chelsea fans over the years than long-distance followers of, say, Scunthorpe County. And the buzz on Fulham Road lately suggests that the Chelsea Football Club might well become the biggest local export of them all.

The club has long had a flamboyant appeal. In the late 1990s, they had so much expensive imported talent, many referred to them as the Foreign Legion. They were led by a player/manager named Gianluca Vialli who grew up in a sixty-room Italian castle. Lots of flash, but success always seemed to elude the team.

“Chelsea had a reputation in those days for pretty football that was ultimately ineffective,” says Rob Hobson, editor of cfcnet, the club’s hugely popular news and discussion website. More bluntly put, Chelsea had the Little Sardinian but not much else to cheer about. Consistently poor on the road and lazy in defence, the derided “Chelsea Millionaires” averaged just sixty points a season through the 1990s, finishing middle of the pack most of that decade.

Over the 2004–2005 season, however, the club was transformed. Abramovich hired a new manager, the utterly confident José Mourinho, who had recently led Portuguese team FC Porto to victory in the European club championship, the Champion’s Cup. And by the end of his first season, Mourinho had revolutionized the club’s play, blending a continental defence with an English-style counterattack. The hybrid has not only resulted in two trophies—the League Championship and the Carling Cup—but Chelsea has smashed records, winning in precisely the areas where they used to be weak. Only fifteen goals were scored against them in league play. They’ve earned the best awaypoints total since the Premier League was established in 1992, and ninety-five points total for league victory.

“If we win the league again next year, the fan base will triple,” Rob Hobson tells me, having seen website traffic already boom from 20,000 users monthly, pre-Roman Abramovich, to 130,000 today.

I met with members of the Chelsea Supporters Group at The Imperial, a Chelsea pub just down from Stamford Bridge on the Kings Road. These aren’t people who excite easily, preferring instead to remind you of leaner times. “We were there when the team was crap,” Gordon says. “The hardest team in London to follow. They hadn’t won anything.”

But on Roman Abramovich, conversation warms. His arrival was like the Kennedy assassination: everybody remembers when and where they heard. And all this because the secretive Russian billionaire grew tired of playing online Fantasy Football and, in the spring of 2003, decided to get involved in the real thing. csg president Trizia Fiorellino tells me how she was at work and her two mobile phones both started ringing at once and didn’t stop for an entire day. Rob Hobson remembers hearing Russian businessman and thinking gangster. “The feeling of the moment was, what exactly is he planning to do with my club?”

What the secretive Russian was planning at that point isn’t clear. Abramovich is the twenty-first richest person in the world according to Forbes, worth over $13 billion (US ). He is unapproachable at the centre of a web of protective corporate layering and he gives no interviews. At the time he bought the club, news outlets scrambled to find a photograph of the man who started selling plastic ducks out of his Moscow apartment and ended up owning the Russian oil giant Sibneft, whose control he secured in 1995 at a fraction of its market value.

What does seem clear is that Abramovich is weirdly committed to Chelsea for someone who—in what seems like a parallel life, lived by a double—also happens to be the very popular governor of Chukotka, in the farthest northeast corner of Russia. He goes to every Chelsea game. He visits the locker room after each one. Even the report that he originally set out to buy Tottenham—and was convinced otherwise by impossible game-day traffic on the high street outside White Hart Lane—doesn’t diminish the heroic timing of his investment. Those Chelsea Millionaires, it seems, were just about to go into receivership.

“We were at the precipice,” Fiorellino says. “Abramovich was a saviour.”

“Four days from bankruptcy,” Gordon says simply.

Abramovich wrote a long series of cheques to change that reality. One to owner Ken Bates, a flamboyant “wide boy” cement magnate who bought the club in 1982 for a single pound from another distressed owner. A second to pay off club debts. Another for new talent, including many English players, eradicating the “Foreign Legion” tag once and for all. A final one to fund a state-of-the-art training facility and football youth academy. Total estimates run to 300 million pounds, a number strongly supporting what Abramovich’s own people declare—that he is in it for the long term. He’s in it to be global.

“We need to increase our international fan base,” Chelsea chairman Bruce Buck said in an interview with British Industry magazine. He was referring to “people in Omaha, that never get to a Chelsea game, but subscribe to Chelsea TV Online and buy a Chelsea replica shirt. People in Osaka doing the same thing.”

Omaha to Osaka. It’s a vision highly evident around Stamford Bridge, with its gaudy Megastore, its architecture more Vegas than SW6 and all those excited, curious international faces. In the West Upper Stand, watching the Arsenal game, I seem to be beside a Dutch tour group. They all grip the seat arms and groan in agony when Chelsea misses a scoring opportunity, exactly like the local man on my other side who has been waiting fifty years.

GLOBALIZATION AND THE MANCHESTER BRAND

Chelsea is not football’s first club to leap from being a local to a global phenomenon. In fact, the discussion of football as an illustration of globalization is well developed. Franklin Foer’s bestselling 2004 book, How Soccer Explains the World, is devoted to the topic, exploring various cultural phenomena through the illustrations offered by football. Sectarian behaviour as seen in the Celtic-Rangers rivalry. The African immigrant experience as lived by Nigerians playing professional soccer in the Ukraine.

But the book also amply illustrates the relatively new global market for sporting loyalties. An American living in DC, Foer loves FC Barcelona. He likes their beautiful play, but also what he perceives as a democratic culture at the club and a low-key approach to marketing, exemplified by their refusal to have a shirt sponsor. In conversation, he acknowledges that his view of the team is romantic, but notes that “when you support a club, you pretty much subscribe to a romantic image of the club or you’re not much of a fan.”

Foer’s book sold extremely well, but, after publication in Spain, Barcelona received him with particular warmth. “I was invited to sit in the president’s box. They had me on Catalan radio ten minutes before game time, asking me my predictions about who would score in what minute.”

Foer attributes the reception to the club’s awkwardness around self-promotion. But Barcelona’s gratitude is just as easily explained by the same broad reality that inspires Buck’s philosophy of expansion and Abramovich’s decision about how 300 million pounds might best be invested. However sophisticated you are in exploiting it, nobody disputes the huge financial gain to be made when a club vaults onto the international stage.

Manchester United is the case study on the topic. The best-known sports club in the world, ManU’s profile has been built the same way Coke’s or Nike’s were in their markets—as a product that delivered quality combined with a recognizable image.

“Delivered quality” is the feel-good part of this equation. After a weak decade, ManU was transformed by new manager Alex Ferguson during the 1990s, climaxing with their 1998–1999 season. Winning the league and the FA Cup that year gave them a coveted double. Then, in the Champions League final, down 1-0 against Bayern Munich, Manchester United scored twice in injury time to take the treble. Three trophies in one year is an unrivalled accomplishment in English football and it was, by sports-page standards, a shot heard around the world. Two weeks later, Alex Ferguson was knighted.

The less celebrated part of ManU’s success, however, lies in branding; the way the club spread its name worldwide and convinced people to identify with it. Two men were behind it. David Beckham is the obvious one, a photogenic midfielder who shoots a pretty free kick and who had the global marketing sense to marry a Spice Girl. It’s never easy to quantify the value of stardom, but when the Tokyo press reported that Japanese girls were shaving their pubic hair in a pattern modelled on the Beckham faux-hawk, global reach had been achieved.

The quieter figure behind the branding campaign was a suit: Peter Kenyon. A self-described Manchester “local boy,” Kenyon was deputy ceo, then ceo, of ManU from 1997 to 2003. During those years, he arranged lucrative sponsorship deals and honed the money-making machinery that brings ManU merchandise to stores all over the world. It was Kenyon who openly spoke of the club as a brand for the first time, who referred to supporters as consumers. It was Kenyon who was in charge when ManU’s stockmarket value—driven by the fastest-growing international fan base in English football—rose to $1 billion (US).

Roman Abramovich showed his astute business sense by writing one of his first cheques not for a talented striker or midfielder, but to secure the services of one Peter Kenyon.

THE AUTHENTICITY TRAP

There is a refrain sung at English football games. It’s probably used in every league by every club that has a loved player whose name fits the rhythm. To the tune of “Guantanamera,” a Chelsea version might go like this:

There’s only one Didier Drogba

There’s only one Didier Drogba

One Didier Drooog-baaa . . .

There’s only one Didier Drooogbaaa.

But in the history of the Manchester United and Chelsea football clubs combined, the following words have never been sung at a game, ever:

There’s only one Peter Kenyon . . . .

Hate is too strong a word, but there is a very real distaste among fans for this successful man who moved his services so dramatically from one club to another.

“Switching allegiance is held in supreme contempt in this country,” Hobson explains to me. “I think I’d be hard-pressed to find anyone who’d admit they liked Peter Kenyon.”

Nevertheless, ManU under Kenyon became rich. At Chelsea, he’s already secured the services of superb Dutch winger Arjen Robben (who had been poised to sign with ManU) and signed the largest sponsorship deal in English football history between the club and Samsung.

What impresses Interbrand director and sports-branding specialist Andrew Milligan about Kenyon’s Samsung deal is the length. “Samsung are long-term global brand builders,” he tells me. “If they’re investing in Chelsea for five years then they’ve got a pretty good feel that Chelsea is the brand to watch in football over that period.”

This reasoning, however, only irritates members of the Chelsea Supporters Group. Mention branding and a wince passes around the table. Football is real. Brands are fake. “It’s an offensive word,” says Paul, an IT manager. “We’re a football club not a brand. If this keeps on, we’ll end up with the ground full of football tourists.”

People like me, I suppose. But it only leads me to wonder what is inconsistent about teams and brands anyway. Branding textbooks sound like they were written with sports in mind. Start with a product that delivers value. Develop a core message and brand personality. Create iconography.

(1) Value: win games.

(2) Brand personality: an articulated team spirit that involves fans.

(3) Iconography: name, jersey, logo, mascot.

What successful sports team is not set on this fundamental tripod? Steinbrenner’s Yankees: countless fall classics, strutting millionaires, and pinstripe suits; the Montreal Canadiens: endless Stanley cups, refinement, the big red C with the smaller H inside; and yes, the Chelsea Revolution too: a title in José Mourinho’s first year, an urban team with flare and grit combined, and blue, blue, blue.

Yet in England there is something absolutely blasphemous about this line of thinking. Ticket prices are soaring (my seat at the Arsenal game cost 250 pounds from a scalper and had risen to 350 by game time). At the famous big-city clubs, increasing numbers of visitors want to see games, and while global strategies are clearly working, many middle-class local fans are beginning to feel the financial cost of their teams’ popularity. That 50 pence they paid for a spot on the Shed End terrace twenty-five years ago seems like a painful false memory.

“There is a worry that the game of football has become disconnected from fans, that the game has basically become a business, not a sport,” Andrew Milligan explains. “Branding, marketing, and television rights all tend to confirm these worries among supporters.”

Local supporters of Manchester United are equally dismayed as the team’s brand has now attracted the interest of yet another mega-rich sports investor: American Malcolm Glazer. Quite unlike Abramovich, however, Glazer is reviled for his interest. Hate is not too strong a word here. When he secured majority interest in the club on May 16, 2005, thousands of supporters began wearing black armbands. The Irish Times (Ireland has the biggest ManU fan base outside of Manchester) ran the headline: “The Day Football Finally Lost Its Soul.” And inside the covers columnist Ian O’Doherty restrained no emotion in describing Glazer as “a hideous carpetbagger.”

The resistance is superficially about finances. While Abramovich bought Chelsea outright, Glazer borrowed 540 million pounds to buy ManU, a liability he transferred to the formerly debt-free club. ManU now faces 46 million pounds in annual interest payments, roughly double the profit earned in the year before Glazer’s takeover. Glazer projects big increases in international merchandise sales, but supporters expect only ticket price increases and a further commodification of their relationship to the old club.

Perhaps the most telling reaction has come from Shareholders United, who owned publicly traded shares in the club until Glazer forced a sell-off and took it off the market. They’ve urged supporters to boycott the team’s sponsors. No Nike, no Vodafone. No Budweiser, Pepsi, Audi, or Fuji. “Support the team,” the group’s statement read, “but the brand is not the spirit of Manchester United.” When Glazer’s three sons visited the ManU stadium in June, irate fans blockaded them inside until police came and rescued them under a hail of bottles and bricks.

The fact is that even if the globalization of football could be stopped, many fans would not want a return to the “good old days” when supporters were genuinely linked to clubs by geography and blood. There were few tourist fans cheering on Stamford Bridge or Tottenham, Leeds or West Ham or many other teams in the Premiership in those days because few would have dared enter the grounds.

“It wasn’t the fighting I was scared of so much as the darts,” a supporter from that bygone era told me, describing how the projectiles crossed the distance between the legendarily rough Shed End terraces and the visitors’ section in the East Stand.

Even if you escaped perforation, the terraces were piss-stained, violent, boozy pens where thousands of fans were crammed into areas that are now mandated by law to seat only a few hundred. Read Bill Buford’s Among The Thugs—described on publication as “A Clockwork Orange come to life”—for horrifying detail on the foulness of these standing-room areas in stadiums across what was then called the First Division. Thousands of fans—to the great shame of Chelsea and many other teams — were also frequently racist. There’s a good reason why ticket prices were 50p in the good old days.

“In the mid-80s the Bridge was a dump,” Hobson says, grimacing. “Now it’s really nice.”

The Irish Times nonetheless lamented the decline of the street-level supporter after the sale of ManU, with columnist Vincent Hogan writing, “The cry of the streets is not a particularly significant sound to men like Glazer.” This, next to a crowd shot of the faithful outside Old Trafford—a sea of shaved heads, the same crowd that proceeded to burn Glazer in effi gy moments later, that hoisted a sign during the last game of the season reading Glazer Watch Your Back. It’s a peculiar kind of nostalgia that mourns the fact that such a crowd can’t make more significant sounds, that they no longer control the club via the terraces.

“The game of soccer in England is infinitely healthier because of the influx of money,” Andrew Milligan tells me. “The trouble with English football is that for regular supporters, [one’s team] is very much part of personal identity. And because of that, teams in the past tended to sell any old rubbish and assume supporters would turn up and buy it because it’s the local club. Now, it’s incumbent on teams to build their brands, to deliver quality.”

The point should resonate particularly for Chelsea fans. Ken Bates had little on-field success and famously referred to the club’s faithful legions as “animals who ought to be caged.” Abramovich has already produced Chelsea silverware. And at every game he presides from his executive box over a clean, terrace-free stadium, where if you act like a hooligan you’ll be expelled indefinitely, where (for the 2004–2005 season) the family section, filled to capacity, was poignantly situated in the renovated Shed End.

THE ROAR

I watch one more game at Stamford Bridge, this one against Fulham. My seat is directly behind the Chelsea bench, so I can watch Mourinho prowl up and down the touch line, brow furrowed with intense calculation. On field, after going ahead 1-0 on a superb goal from Joe Cole only to have it clawed back by Fulham, Chelsea is again leading on a Frank Lampard goal and the crowd is in fine voice. Just now, to the tune of “La Donne è Mobile”:

José Mourinho,

José Mourinho,

José Mourinho.

Simple, but heartfelt. He may be part of the new brand—brash, confident, gritty—but he’s bringing them the league title and they love the guy. “One of the heartening things about this new era,” Barcelona fan Franklin Foer told me, “is that all this corporate fakery doesn’t really in the end diminish the true passion that local fans have for the game.”

At the time of writing, Foer’s club was on the verge of trumping Chelsea by signing the biggest new shirt sponsorship deal in football. The democratic team that never deigned to have a sponsor on their red and blue striped jerseys will now advertise that force for Western liberalism: the Chinese national government.

So brands win over ethos. Or maybe, better put, the clubs were brands all along, only, as Milligan puts it, lacking the commercial discipline of true brands and isolated from competition. In which case, perhaps the Chelsea Supporters Group is less offended by brands than they are by the potentially daunting popularity of their own. Even my friends from the city, in their nice checkered jackets and beautiful English shoes—haven’t they long been complicit in a brand transaction, buying for effect? Aren’t they, after all, slumming a bit? When my aromatherapy products entrepreneur recalls the days when the Shed was “nasty but really quite nice,” I don’t imagine for a minute he ever threw a dart. He’s identifying the sizzle with that comment, not the steak.

On the field, in any case, the players and José Mourinho are nicely illustrating the new global game, blending two styles to devastating effect. The first, distinctly continental. Chelsea move up and down the field as a welded unit, defence from front to back. Fulham take runs through the midfield and get caught in traps, dead ends, get turned around and dispossessed.

The second style, though, pure English: the counterattack. In Chelsea’s case, it inverts the defensive posture into an offensive one with startling speed and scythes downfield. At its most brutal (and most English) form, some teams simply play a long ball downfield for a sprinting striker. But at its best, it’s like Chelsea’s third goal, which seals the game and effectively the league championship.

Fulham attacking, again. Luis Boa Morte this time, cutting to the left, getting trapped by Glen Johnson, forced to pass back. Fulham’s Steed Malbranque collecting the ball and taking his own run, held up by Jiri Jarosik this time, who forces the frustrated pass again. And then comes the transition. So quick that in order to see the instant where Mourinho’s newly moulded team changes direction from defence to attack, I have to wait for video replay. Downloaded from Chelsea TV Online, naturally. Watched in the comfort of my office back in Vancouver.

From there, I could see how it worked. Malbranque’s pass plucked neatly from the air by Chelsea’s Tiago, and cleared to space. A second of lag, as Tiago moves to the ball, head up. And then, across the Chelsea formation, a sense of surge, flow reversing. They are no longer sucking the attack into dead ends, they are looking down long avenues running the other direction. Tiago reads the field, then passes sharply, bisecting the defence and hitting striker Eidur Gudjohnsen at full gallop. Gudjohnsen runs a simple line to his right, cutting out pursuers, slotting the ball past a helpless keeper and into the net. The team’s appeal is fully captured in that move: grit and flair, resolve and no small amount of arrogance, too. But more importantly, the online replay seemed, for that instant, to be the better way to view the game—for the information, for the sense of tactics and logic that have been revealed.

But then, what I can’t feel, what I can only remember, is the roar that followed. It was another of those crowd sounds for which no number of television transmissions could have prepared me. A staggering sound that entered my head and took the long way leaving, which seems to bend the skull just slightly with its pressure. I vainly tried to record it on my Dictaphone, at the match. And I’ve listened to it several times since, trying to recapture the sense of it, the prickling scalp, the sense of closeness to something large and entirely unknown. But while I’ll always think of the roar, maybe even tell people about it, be bound somehow to the club by having stood on my feet and briefly joined in making it, I know now that I didn’t take any of it away with me. That whole sound was real only for the instant of its collective utterance, after which it was carried away in its thousands of fragments, up the crush-packed pavement and off down the Fulham Road.