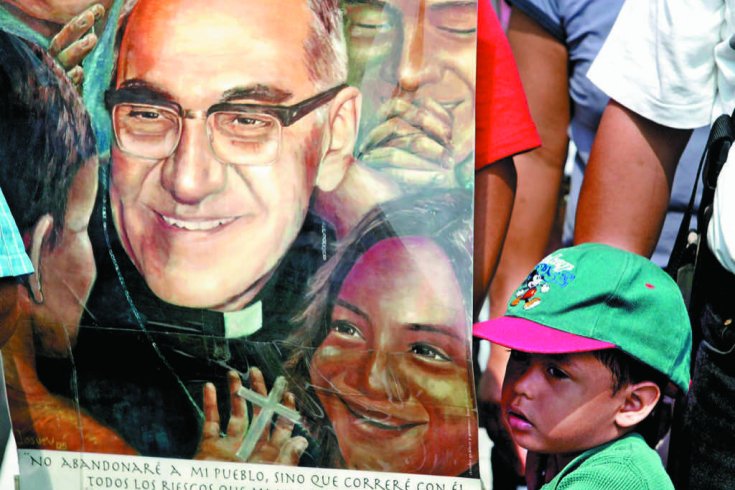

san salvador—Strong winds swirled through the central plaza in San Salvador, rippling the forty-foot banner depicting Archbishop Oscar Romero and tipping the handheld placards borne by local and international solidarity groups. The Salvadorans, steeped in the biblical association between wind and the Holy Spirit, sensed perhaps that the forceful gusts—unusual for El Salvador in April—held more than meteorological significance, and lent credence to their chant of “Que viva Monseñor Romero!” No less significant was the crowd, 30,000 strong, gathered around them for the rally and Catholic mass concluding a two-week celebration in honour of the twenty-fifth anniversary of Romero’s death. The festivities had been a time to reflect on Romero’s place in history, the challenges his spiritual heirs face today, and the future of liberation movements in Latin America.

An assassin’s bullet pierced Romero’s heart on March 24, 1980, as he celebrated mass in San Salvador. A formerly introverted church administrator, he had experienced a type of metanoia shortly after becoming archbishop of El Salvador in 1977, when his good friend, Jesuit priest Rutilio Grande, was assassinated. The murder transformed him into a champion of human rights.

Romero once observed that the gospel “illuminates beautiful things, but also things which we would rather not see”—a belief that compelled him to challenge El Salvador’s ruling class, which lorded over a country where most of the people lived below the poverty line and six out of ten children died at birth. He declared that these odious conditions were the fruits of corruption, greed, and a sinful will to power, not God’s will, as five centuries of “conquistador” theology and Church practice in Latin America suggested. In his Sunday homilies, broadcast throughout the country on the radio, he protested government sponsored murders and death squads, and denounced the economic conditions that would fuel a civil war in El Salvador from 1980 to 1992 and claim some 75,000 lives, including those of eighteen priests (their murders portended by government leaflets bearing the slogan, “Be a patriot, kill a priest”).

For many, Romero embodied liberation theology, which had argued since the 1960s that Christian neutrality in the face of injustice was impossible and that the Church must adopt what the Latin American Bishops Conference, meeting in Medellín in 1968, termed a “preferential option for the poor.” After Romero’s death, the movement continued to perturb Latin America’s political and ecclesiastical elites, who chafed at the notion of the Church replacing its traditional teaspoons of charity with the bulldozers of justice. It persevered through the tumult of the 1980s, when the Reagan administration, fearing Communist domination of Central America, sent an average of $1.5 million (US) per day in aid to El Salvador’s military controlled government. And it also persisted through Vatican investigations that led to the silencing of several priests and liberation theologians.

The crowd at the memorial mass was testament to liberation theology’s tenacity and scope, filled as it was with indigenous groups, women’s organizations, and religious activists from across Latin America, as well as solidarity groups from Canada, the United States, Africa, Europe, and Japan. Costa Rican scholar Elsa Tamez observed at a conference held during the celebrations that liberation theology has persisted because it speaks to people’s needs. “In Latin America, we are worse [off] than in the 1980s,” she said. “Poverty—worse. Unemployment—worse.”

The justice-oriented Christians at the mass were veterans of such battles as the Zapatista liberation campaign in Chiapas, Mexico, the successful protests against water privatization in Bolivia in April 2000, and the ongoing fight to overturn the Central American Free Trade Agreement signed last year by several countries, including the United States. Vatican indifference, and in some cases outright resistance, to such issues led Brazilian theologian José Comblin to quip that the Catholic Church has adopted a “preferential option for the rich.”

Curiously, the mass fell on the same day as Pope John Paul II’s death. Many in the crowd speculated about who would be the next pontiff, but few would have guessed, or prayed, that it would be Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger. As the Vatican’s chief adviser on doctrine from 1981 to 2005, the cardinal (now Pope Benedict xvi) spearheaded a campaign to “correct” liberation theology’s errors. Romero didn’t live to see Ratzinger’s 1984 Instruction claiming that the theology was tinctured by Marxism but he was visited by Vatican investigators three times during his tenure as archbishop. Today, Romero’s case for canonization is moving slowly, despite the near-doubling of the number of saints under John Paul II.

Such troubles seemed somehow small, though, to the cheering crowd watching the origami cranes that flew nimbly in suspension above the altar, the beams of flashlights that shone across the windswept stage, and the fireworks that outlined Romero’s face in the sky. No matter what the official process of canonization yields, Romero has already been deemed “Saint Romero of the Americas” by the voiceless poor for whom he gave his life. This, in fulfillment of a promise he made in an interview just weeks before his death: “If they kill me, I will rise again in the Salvadoran people.”