Nearly four years after the destruction of the World Trade Center, I surrendered to a long-held curiosity and joined the United States Army. There’s a popular misconception that you can walk into a recruiting station and sign up. But the American army is the most sophisticated fighting force in history and it doesn’t accept just anyone. After a rigorous interview process and several hours studying the materials, I climbed onto the recruiting bus and headed off to basic training at Fort Benning, Georgia.

At boot camp I learned to handle the m16, the fearsome saw, and other modern weapons. After qualifying on the shooting range, I donned night-vision goggles and stalked through the spooky corridors of the urban-warfare facility, firing by instinct at pop-up targets of swarthy enemy soldiers or sometimes a shopkeeper armed only with a bagel. After twelve weeks of training, my outfit, the 22nd Infantry Regiment, shipped out to Iraq. Two days later, I got my first taste of combat. I was on patrol near Baji when my Bradley Fighting Vehicle came under sniper fire. I pursued the gunman into a village before realizing we’d been drawn into an ambush. Bullets whizzed by; a rocket-propelled grenade struck me in the chest, transforming my upper body into a mushroom cloud of pink mist and ricocheting my head off a nearby wall. At this point it occurred to me that fighting the war on terror was going to be more challenging than I expected. With a click of the mouse, I went back to reboot camp and started over, humbled but not discouraged. In this man’s army — a computer game called America’s Army — getting killed in action is nothing more than a temporary embarrassment.

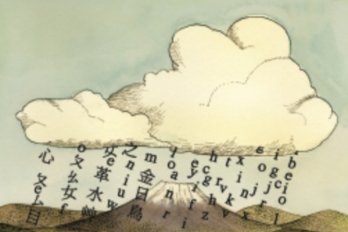

America’s Army is financed and produced by the United States Department of Defense and is designed to lure young men into the forces. But the technology used to create the video game is at the centre of a much larger question that many Americans are beginning to ask themselves: like the teenage boys seduced into playing America’s Army, are they too going to be corrupted just as subtly by the Pentagon’s growing use of digital technology to create false realities? Digital technology has enabled military scientists working at the intersection of fantasy and reality to develop radical new weapons that will target the brain not with a bullet, but through the creation of a seamless fabricated reality. This tactic will, according to psychological war experts, help the American military not only exert behavioural control over the enemy on the battlefield, but, more ominously, over American public opinion.

The US Army used to call this sort of strategy “psyops” (psychological operations) and it even maintains a department of psychological warfare at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. Once dismissed as an idiot uncle of the military establishment, the Civil Affairs and Psychological Operations Command has mutated into a hydra with tentacles in every level of the military. Psyops can now manufacture eerie simulacra of reality, meaning that in the future it will become increasingly difficult to separate real news from combat footage, communiqués, and hostage videos fabricated by all sides for their own purposes. After all, why influence the news when you can invent it and have a digitally created Dan Rather present it? Thomas X. Hammes, a counter-insurgency expert with the US Marine Corps, says these weapons are being employed today to fight the war on terror and will be used even more in the future. “The notion that we can win this fight with a lot of [conventional] war toys is a fantasy,” he says. “It’s really important for people to understand that we’re no longer fighting foreign wars with guns and bombs. We’re fighting with ideas.”

During the 1980s, President Ronald Reagan increased defence spending by 35 percent, to more than $400 billion (US) a year, and promoted the idea of a futuristic missile shield over North America — a notion some scholars believe was inspired by the Paul Newman movie Torn Curtain. The Soviet Union, burdened by an increasingly inefficient economy, couldn’t keep up with US military spending and by 1991 had collapsed. Many hoped that the demise of communism would usher in a new era of global co-operation, but, with the Soviets vanquished, the United States launched its plan to remake the world in its own image.

In 1997, a number of people who are now top officials in the current US administration, including Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, Vice President Dick Cheney, and national security strategists Paul Wolfowitz and Richard Perle, launched a think tank called the Project for the New American Century. The group argued that it was time to take pre-emptive action to enforce US interests abroad, including removing unfriendly governments. “As the twentieth century draws to a close,” according to the project’s statement of principles, “the United States stands as the world’s pre-eminent power. Having led the West to victory in the Cold War, America faces an opportunity and a challenge. Does the United States have the resolve to shape a new century favorable to American principles and interests?”

Reshaping the world in America’s image would not only involve massive funding to produce new futuristic weapons, it would also require the Pentagon to enlist the support of Hollywood, where the arsenal of digital technology is advancing almost daily. Soon after coming to power in 2001, President George W. Bush acted on the first leg of this strategy when he announced that he was pumping hundreds of millions of dollars into such organizations as darpa, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, which grants research money to weapons developers. Since then, development has begun on dozens of weapons that close the gap between old-fashioned military hardware and the virtual future. One of the most promising, in the Pentagon’s view, is the Brain Machine Interface, a system of embedded neural transmitters and computer software that bridges thought and action. It is being developed by Duke University scientists, who have already created a computerized system in which a lab monkey can move a robotic arm in a laboratory 1,000 kilometres away just by thinking about it. In the future, military commanders with brain implants will use more advanced versions of this technology to deploy unmanned gun ships and robotic tanks in battlefields half a world away.

Bush has also revived plans to develop new real-world weapons systems, including fighter jets that do not require pilots and a new generation of smart bombs. And he agreed to spend billions on the missile-defence program envisioned by Reagan twenty years earlier. In support of the plan, defence contractor Lockheed Martin is building an airship twenty-five times larger than the Goodyear blimp. The airship will serve as a communications platform where attacks on enemy missiles will be coordinated.

The military is also planning unmanned spaceships that will carry huge tungsten bolts, nicknamed “rods from God,” that can be dropped with devastating impact on even the smallest target anywhere on the planet. Recently, retired Air Force Secretary James G. Roche described these space weapons as mandatory for any twenty-first-century arsenal. “Space capabilities in today’s world are no longer nice to have,” he said. “They’ve become indispensable at the strategic, operational, and tactical levels of war. Space capabilities are integrated with and affect every link in the kill chain.”

As futuristic and powerful as this new generation of weapons will be, Bush, perhaps more than any other recent president, is guided by an idea once espoused by Napoleon: “There are but two powers in the world, the sword and the mind. In the long run the sword is always beaten by the mind.” According to many strategists, even if the United States wins on the battlefield, it must ultimately win over the minds of the citizens of a country it is invading with propaganda in order to remake the world in its own image. Hammes, who has trained insurgents around the world, believes it was precisely the military’s failure to win over the hearts and minds of its enemies that led to the United States’s defeat in a number of conflicts over the past thirty years. Today, it is no closer to winning over Iraq than it was when it invaded in 2003. “We were defeated in Vietnam, Lebanon, and Somalia, and we’ll lose in Iraq the same way,” says Hammes. “We’ll win the battles, but we’ll lose the war [of ideas].”

With the United States engaged in a protracted war against terrorism and bogged down in Iraq, the Pentagon is keenly aware of these past failures. William Arkin, an author and former military affairs analyst for the Los Angeles Times, says that the military is growing frustrated with its inability to stay ahead of the terrorist threat, and is anxious to enlist Hollywood and its digital expertise in its fight. “Traditionally, the military has been an innovative force in technological development,” he says. “But about ten years ago, with the digital revolution, the civilian world really began pulling ahead of the military. The army just can’t compete with Hollywood or Microsoft when it comes to digital wizardry.” Microsoft alone spent $2 billion (US) developing its Xbox game technology. It is that kind of muscular research spending and product development that has convinced the Pentagon that it must break down the walls between the military and the entertainment industry.

The first of several recent high-profile Pentagon initiatives in Hollywood came in 1996, when top military officers travelled to Los Angeles to brainstorm with executives from Industrial Light & Magic, Intel, and Paramount about storylines for their combat simulators. This wasn’t the first time the military had gone to Hollywood. During the 1960s, the cia was intrigued by the emergence of television and by experiments indicating that moving images produce a shift from left-brain to right-brain neural activity, which in turn induces a sort of chemical trance that suppresses judgment and heightens suggestibility. The researchers learned that once viewers “suspend their disbelief,” they become vulnerable to the values and messages embedded in the drama.

So it wasn’t surprising that soon after the meeting in 1996, the Pentagon proposed a working partnership with Hollywood. Three years later, it announced that it would build a new $45-million (US) production house in Los Angeles and that it intended to hire many of the screenwriters and producers who had attended the meeting. The new facility was designed by Herman Zimmerman, the award-winning designer of a number of Star Trek episodes, and dubbed the Institute for Creative Technologies. The institute soon became a sandbox for forty-five writers, directors, and special-effects technicians, many of them Academy Award nominees.

Their first project was the development of a total-immersion simulator that gives soldiers a preview of real-life combat situations. The simulator consists of a virtual-reality theatre with a 150-degree screen and a Dolby sound system. Inside, young soldiers-in-training can pick their way through a number of spooky combat environments. A typical program recreates a blown-up building strewn with garbage, jagged rebar, concrete, and splintered furniture. Through a hole in the virtual wall the young trainee can peer out at a wasted city, where sparrows dart through the smoke, Arabic music filters up from the street, and a helicopter gunship thunders overhead.

After the attack on the World Trade Center in 2001, the military returned to Hollywood — this time with new urgency — to again meet with studio heads and producers. Their goal: to enlist the entertainment industry in a sweeping campaign to rally public support for the military and the war in Iraq.

According to the entertainment trade paper Variety, those attending the meeting at the Pentagon’s studio included the presidents of cbs, hbo Films, Warner Brothers Television, and prominent producers and writers such as Steven E. de Souza (Die Hard), Joseph Zito (Delta Force One), and Spike Jonze (Being John Malkovich). One of the producers at that October 2001 meeting was Lionel Chetwynd (The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz). “There was a feeling around the table,” he later recalled, “that something is wrong if half the world thinks we’re the Great Satan. Americans are failing to get our message across to the world.”

The meeting was off-limits to the media, and Chetwynd revealed little else. But a White House spokesperson later said that the government was asking movie moguls for their help in selling America’s image to audiences around the world. Said the spokesperson: “The administration will share with studio executives the themes we’re communicating at home and abroad, of patriotism, tolerance, and courage.” Military officials also reminded the producers of certain “resources we might have in government [that would] be helpful to them.”

David Robb, a former investigative journalist with the Hollywood Reporter and author of Operation Hollywood: How the Pentagon Shapes and Censors the Movies, explains what those “resources” might be. “The government,” he said, “is basically offering filmmakers access to expensive military equipment in exchange for editorial control over their scripts.” He sees a dangerous and growing interdependence between the film industry and the military. “It’s all about money,” he says. “If you’re making a movie that requires F-14 Tomcats or combat helicopters, you can save millions of dollars by making a quid pro quo arrangement with the Pentagon. They’ll loan you the equipment for peanuts — for the price of fuel, let’s say — if you let them control the script. Everybody is happy. The filmmakers get access to war toys. And the military establishment gets to flog its pro-war message to millions of moviegoers.”

As a result of this partnership, a string of new movies partially subsidized by the Pentagon will soon be showing up at theatres. In the high-profile No True Glory: The Battle for Fallujah, scheduled for release in 2006, Harrison Ford will play a heroic American general leading his troops into a hornet’s nest of insurgents in the Iraqi city. It’s unclear to what extent the Pentagon influenced the script, but the screenwriter said the movie “will focus on the bravery of our soldiers and point out why our military can be relied upon to do the right thing.”

To ensure their pictures cast US soldiers in the best possible light, producers who want access to military hardware must submit their scripts to the Pentagon. And according to Robb, military censors “always” insist on a rewrite. “They don’t ask for revisions in the script,” he says. “They tell you.” There are countless stories of the Pentagon trying to bully producers. Clint Eastwood, for example, was infuriated when the Pentagon refused to support Heartbreak Ridge because it contained a scene in which Eastwood’s character shoots a wounded Cuban soldier.

Once the revised script satisfies the military, the Pentagon dispatches a “minder” to the set, to make sure the story isn’t changed at the last minute. “Their main criterion,” says Robb, “is that a script has to ‘aid in the retention and recruitment of personnel.’ But Hollywood has crossed the line into the glorification of war. We’re getting a steady diet of this kind of propaganda, and I honestly believe it’s making us into a more warlike people.”

During the 1990s, before aligning itself with Hollywood, the military had conducted digital morphing experiments at Los Alamos National Laboratory in Santa Fe, New Mexico, the birthplace of the atom bomb. They attempted to recreate individual voices by “dragging and dropping” taped words into sentences, but the results invariably sounded phony and robotic. George Papcun, an expert in phonetic synthesis at Los Alamos, later improved the technology and used it to develop several fictive scenarios, including one in which General Colin Powell had been kidnapped by terrorists. Before a group of officers gathered for the demonstration, Powell announced, “I am being treated well by my captors.” In another demonstration, Papcun played an audiotape that had supposedly just been received from General Carl W. Steiner, former commander of the Special Operations Command. “Gentlemen!” said Steiner. “We have called you together to inform you that we are going to overthrow the United States government.”

But these experiments were amateurish compared to the work being done by technicians in Hollywood and Silicon Valley. Their sophisticated digital morphing techniques first appeared on movie screens in 1991, when audiences across the world gasped as a snake-eyed killer robot in a policeman’s uniform morphed out of a tile floor in Terminator 2: Judgment Day. Two years later, Jurassic Park used the same technology. It is the expertise behind the creation of these lifelike digital scenarios that the Pentagon covets. In the movie In the Line of Fire, for example, Clint Eastwood plays an aging Secret Service agent who happened to be on duty in Dallas on the day President John Kennedy was shot. To send Eastwood’s character back to 1963, Hollywood computer specialists used digital morphing to lift Eastwood from an early Dirty Harry movie, gave him a military haircut and a skinny tie, and dropped him into an actual news clip of Kennedy’s assassination, now showing Eastwood rushing to the president’s side.

Ford Motor Company also blurred the boundary between fantasy and reality when it raised Steve McQueen from the dead to advertise its 2005 Mustang. In a scenario cribbed from the movie Field of Dreams, a young farmer builds a winding racetrack on his farm. He circles the track a few times in his new Mustang, then McQueen (who died in 1980) comes sauntering through the cornstalks. The farmer flips the keys to McQueen, who roars off in the car, which Ford designed in homage to the 1968 muscle car McQueen drove in the classic movie Bullitt.

So would the military use similar technology to fabricate news clips, communiqués from insurgent fighters, and videotaped confessions from foreign villains? Perhaps the better question is, why wouldn’t it? Imperial powers have always used disinformation and deceit to advance their military goals. And the American military openly admits that deception will be an important tool in the wars of the future.

Creating virtual worlds to control public opinion and influence the battlefield was the disturbing theme of a paper entitled “Psyop Operations in the 21st Century,” published by the United States Army War College in 2000. The author enthuses over the possibility of using digital morphing techniques to create “simulated and reproduced voices, fabricated provocative speeches delivered by virtual heads of state, and projected images of actual life situations.” The paper concludes ominously that the twenty-first century will be “an amazing place” for achieving “mind and behavior control.”

Imagine, for example, the digitally reproduced president of a small country the United States is fighting appearing on his country’s television network and ordering his army to put down their weapons, or a similarly recreated leader of a democratic faction in Iran inviting the American army into the country to rescue them and dismantle Iran’s growing nuclear program. In fact, Arkin notes that during the Gulf War, this is precisely the technology psychological war planners wanted to deploy in a bid to destroy Saddam Hussein’s reputation with his allies. “They considered faking a video that showed Saddam indulging in sexual perversions, crying like a baby, and exhibiting other types of unmanly behaviour,” he says. “But they backed off because they were concerned about a bad reaction from their Arab partners.” Arkin says the United States also crafted a plan to project a huge holographic image of Allah into the skies over Baghdad, urging Iraqis to overthrow Hussein.

In the end, the military didn’t proceed with these initiatives, but Arkin says the Pentagon’s reservations were strictly logistical. “They scrapped the hologram because it required huge mirrors,” he says. “And there were other concerns, such as what is Allah supposed to look like? I don’t think ethics played any role at all in the decision to back off. These people tend to put military objectives ahead of ethics. And that’s worrisome.” While Arkin says the Pentagon has yet to directly target Americans, it has the growing capability — and perhaps motive — to do so. “There’s no evidence they’ve cooked up faked videos to influence public opinion here at home,” he says. “But there’s a danger that in the ongoing fight for hearts and minds, [it] may prove too tempting to resist.”

There are disturbing precedents. The head of the cia resigned last year after acknowledging that intelligence reports concerning Hussein’s nuclear weapons arsenal, which were used to justify the attack on Iraq, may have been faulty. Some analysts believe they were deliberately fabricated. If such false information can be used to sway public opinion today on such a critical issue, it’s not hard to imagine, for instance, North Korean leader Kim Jong Il appearing digitally on the cbs Evening News boasting about his arsenal of nuclear weapons and his plans to use them against the United States.

Some veteran psychological war operatives believe the military has already crossed that boundary and is moving toward manufacturing virtual newscasts. Retired Army Colonel John B. Alexander is a former intelligence officer with the US Army and author of Future War: Non-lethal Weapons in Modern Warfare. Does he believe that the Pentagon would invent the news Americans are watching to achieve military objectives? “As sure as a heart attack,” he says, without hesitation. “I guarantee they’re doing it already.”

There may not be evidence to prove Alexander’s allegations, but the military to enshroud the American public in a cloud of digital illusion. Clear indications of this surfaced in February 2000, when Colonel Christopher St. John, commander of one of the army’s psychological operations groups, gave a speech in which he called for “greater co-operation between the armed forces and media giants.” With some pride, he revealed that his team had managed to embed some psychological war operatives from Fort Bragg at cnn. They were doing editorial work. While it isn’t clear what the intent of the operation was, they were recalled when their presence at cnn was revealed. Admitted Major Thomas Collins of the US Army Information Service: “They worked as regular employees of cnn and helped in the production of news.”

It’s impossible to run an empire without young men who are willing to risk their lives on foreign shores. With troops stationed in more than 120 nations around the world, the US military is now more widely deployed than at any time since World War II. Virtually every soldier with combat training has been sent overseas, and the Army Reserve, comprised basically of weekend soldiers, makes up about 40 percent of the troops in Iraq. The army estimates that it will need at least 74,000 fresh recruits annually to sustain these troop levels. But since the reinstatement of the draft is widely viewed as politically unworkable, where will all those young recruits come from?

The hope is that such video games as America’s Army, which was the brainchild of United States Military Academy professor Colonel Casey Wardynski, will seduce young men into joining. The army budgeted $7 million to develop the project, and Wardynski partnered up with Michael Capps, a virtual-reality engineer at the United States Military Academy with four degrees ranging from mathematics to creative writing. After three years in the marketplace, America’s Army has proved to be a smash hit, with players having logged more than 60 million hours of online combat.

To promote the game, real soldiers hold tournaments at video-gaming conventions and visit youth-oriented events such as nascar stock car races, where they set up kiosks stuffed with army paraphernalia, real weapons, and computer terminals at which kids can try America’s Army. The US Air Force, the Marines, and the Special Forces have also produced their own games. All this is clearly part of a much broader strategy — one in which digital games, so effective in bringing teenage boys into the army, are expanding to turn the field of battle, and the struggle for the public mind, into a virtual game in which reality and fiction merge.

Of course, as it stands today, reality is still all too real for soldiers in the field. The day Patrick Resta, twenty-six, arrived in Iraq, one of the soldiers in his unit had half his head blown off by a roadside bomb. They bagged his body and set up camp as local villagers shot rocket-propelled grenades at their encampment. “In the confusion,” he says, “this car came down the road, dragging a piece of metal and throwing off sparks. The next thing you know, thirty guys from my unit opened fire on the car, which, as it turned out, contained three innocent civilians, one of them a twelve-year-old boy. This is all in my first three hours in the country. My entire tour of duty was a complete clusterfuck.” He now volunteers for a group of ex-soldiers called Veterans for Peace, visiting schools in the Philadelphia area and telling kids about the reality of war. “It’s not a video game. You’re shooting real human beings, and it’s a horrific thing. These army recruiters show up in their crisp uniforms to talk about adventure, heroism, free college tuition, and so on. The kids are young, and they don’t think their own government would lie to them. But I tell them, ‘Hey, they’re lying, to everybody. Don’t believe any of it.’”