soweto—“Shoot the may-or, the may-or, the may-or! I shot the may-or, the may-or, the may-or!” Roughly 500 men, women, and children march down Rissik Street, through the business district of central Johannesburg, and toward city hall. At each intersection they stop, sit, block traffic for at least a minute, and then move on. Seemingly arising out of nowhere and constituting a regular annoyance to pedestrians and drivers alike, these spontaneous protests are always led by women from the city’s poorest townships. They dance, gyrate, shout, “Shoot the may-or, the may-or,” and demand that Mayor Amos Masondo grant them access to life’s basic necessity: water.

The sight of hundreds of disenfranchised blacks and “coloureds” is a stark reminder of a still-divided South Africa. I had come to Johannesburg to see Virginia Setshedi, an activist working with the Freedom of Expression Institute. Her organization is gathering evidence for a constitutional court challenge against the government for violating a fundamental tenet of the new constitution: access to a sufficient water supply. Virginia introduced me to Ratha Moloi, a resident in a new settlement area in Soweto called Phiri Extension. He took us to his new house, one that he bought himself, a fact that distinguishes him from his neighbours, most of whom live in government-built shacks. But while Ratha is employed, upwardly mobile, and part of a new, more hopeful South Africa, he’s also riddled with insecurity and surrounded by grinding poverty. Like his neighbours, Ratha has no water.

Ratha escorts us inside the front door, passes a small television in the front hall, and shows me his bathroom. It is bone dry. His daughter, still in her school uniform, is working on her homework at the kitchen table. She gives a half smile as Ratha explains how the government took away his water supply.

The infrastructure of Soweto reflects the apartheid era. Roads are unpaved, houses are falling apart, and the water system is entirely inadequate. In 2001, the cash-strapped city government formed Johannesburg Water and privatized water and waste management for Johannesburg’s 3.5-million residents. In 2003, mayor Masondo announced a 450- million rand deal (about $100 million) with Johannesburg Water to replace Soweto’s rusted and crippled pipes, the source of much of the seven billion litres of water lost to leakages each month. Today, new pipes are being laid throughout the township, and with them the company also installs pre-paid meters that turn water into a pay-as-you-go service. The government provides 6,000 litres of free water a month, but charges for additional usage at market prices. (It is common for South African families to have eight or nine members; a Canadian family this size uses an average of 82,320 litres per month.)

Ratha does not have a pre-paid meter, and his current water bills from Johannesburg Water far exceed the monthly flat rate of 62 rand previously charged by the government. Ratha shows me a water bill dated March 3, 2004, for 17,960.95 rand. Like the vast majority of Soweto residents who are also receiving exorbitant water bills, Ratha earns less than 10,000 rand a year. When he couldn’t pay, the company cut him off completely.

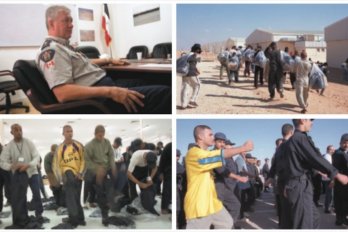

Though Johannesburg Water promised to provide a more efficient water system, Soweto residents have learned that a house visit from the company means only pay-as-you-go water and higher prices. With water shortages making it impossible for locals to grow food in their own and community gardens, and with water theft more commonplace, tempers are rising. Company representatives are chased away, and, when workers tried to install new pipes in Phiri, residents snuck out at night with shovels and flashlights and undid the company’s work. One company worker was shot twice in the chest while installing equipment. He survived, but, with added security, the water company is persevering with its meter-installation plan.

The new South Africa that encouraged Ratha to buy his own house also promised him access to water. And the constitution guarantees it. By providing a mere 6,000 litres for free each month to each household, the government insists that it is living up to its obligation. But, for Ratha, and other men and women of Phiri, those 6,000 litres barely get them through two weeks.

As we drive away, Ratha and his neighbours gather on the lawn in front of his house. They are speaking in Zulu about the court challenge on behalf of their community. For South African blacks it represents a unique opportunity. In turn, an activist South African constitutional court could choose to force the government’s hand, and, in so doing, impose at least part of the better life promised in the African National Congress victory of 1994.