Edwige Birlouez won’t participate in her town’s medieval fair. She won’t don velvet robes or drink mead. And she most certainly won’t demonstrate reliure: that would give the impression that bookbinding is an archaic art, to be dragged out once a year along with the torture rack.

Unlike the bowyer or the cooper, the bookbinder still performs a necessary function. The library shelves of France are sagging with disintegrating volumes – Bourbon-dynasty Bibles, Revolution-era death records, and mass-produced nineteenth-century novels, all languishing from lack of care. Hence the need for those who can tend to them.

To spend even a few minutes with Edwige Birlouez is to discover her passion for the printed word. Birlouez, who is fifty-four, lives in the fortified town of Semur-en-Auxois, two hours east of Paris, and works in a converted primary school. She believes that books are not simply our intellectual record; they are humanity’s hope. “Bookbinders,” she says, “are guardians of the future.”

Despite the apparent demand, according to Birlouez, the art of book-binding is in steep decline. She cites several reasons, the first being a lack of public appreciation. Few apart from bibliophiles and librarians grasp how much will be lost if those crumbling texts become unreadable. And while France has some seven hundred bookbinders, most are weekend hobbyists for whom the art is more of a craft, on par with candle-making. Birlouez credits the amateurs with having kept bookbinding alive when the professional guilds were banned and then dismantled during the French Revolution. But, in the absence of a formal tradition , these amateur techniques have contaminated the art. “Bookbinding will disappear,” she warns, “unless, right away, something is done.” She aims to restore the strict guild culture, particularly its devotion to “the art of working hard.”

Birlouez fell in love with bookbinding when she was fourteen, after at-tending a bookbinding workshop at school. But her parents, fearing that a career in the obscure field would lead to a life of poverty, tried to steer her toward something more sensible. After studying sociology at university, however, she apprenticed as a bookbinder. For some years she worked as a corporate-communications and human-resources trainer, but that experience of “intimacy with the book” never left her. In 1997, she earned her professional certificate in bookbinding at L’Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs and committed herself to her first love.

In 1999, she founded Les Ateliers d’Or, the only French institution solely devoted to vocational training in book-binding. Here, she instructs groups of a dozen or so students – as in trade guilds of the past – in the art of repairing an old book or even crafting a new one from scratch for special one-of-a-kind art books or limited editions. A core of well-trained bookbinders, she says, will be the profession’s best promoters.

There are more than thirty steps to restoring a book, with more than seventy distinct techniques, drawing upon the expertise of several professions: tailoring, leatherworking, carpentry, draftsmanship, and printing.

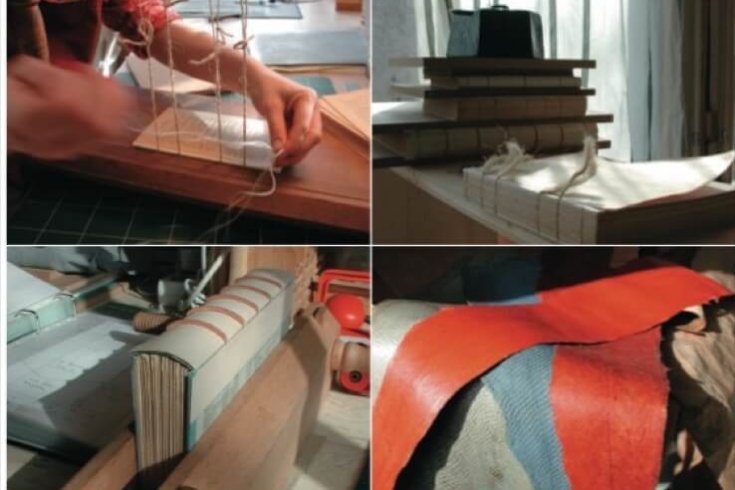

The meticulous process begins with cutting and removing the threads that bind together each signature. (Historically, signatures developed when multiple pages were printed on massive sheets, which the bookbinders then folded, sewed, and bound.) Old glue is cleaned away and each page is assessed for damage and repaired. Back in order, the signatures are held by a vice, where shallow cuts are made horizontally across the spine to make new holes for re-sewing. These cuts also determine the placement of the nerfs (literally, “nerves”), the raised bands that appear on the spines of antique books, now merely a stylistic holdover from when the binding threads were not hidden in grooves as they are now.

The body of the book is then brought to the cousoir, a vertical wooden sewing frame strung with hemp. A needle and linen thread are used to sew each signature, one by one, to the vertical cords.

Next, in a series of precise steps, the cover-boards are attached, the book’s edges trimmed flat, and muslin strips are glued to the spine. Goat-, cow-, sheep-, or even fish-skin leather is cut, pasted, and pinched to define the spine; cover cloths and endpapers are next. Should the book merit it, title and author are gilded on the leather spine using a hot bronze stamp and gold leaf. Between many of these steps, hours or days must pass for glue to dry and for paper and cardboard to be pressed perfectly flat.

A bookbinder’s real battle is with time – to rescue a book from past ravages and protect it for the future. But binders can never know if they’ve truly won the second part of that battle. Birlouez’s confident that her rescued books, treated with methods unchanged since the Middle Ages, will stand that test for at least several centuries. The most modern elements in her atelier are the nineteenth-century hand-cranked presses and paper cutters, and the pots of vinyl-based glue.

Each apprentice (or “future colleague,” as Birlouez prefers to call them) labours at an individual work table. Stacks of books sit under iron weights. The faint odour of glue and sounds of hammer blows fill the air. Birlouez marches in as the students work (average age: thirty) and claps her hands to get the class’s attention, calling out, “Alors, mes enfants.” One afternoon, she lectures on the history of books; another, she complains that some tools haven’t been stored properly.

Birlouez firmly believes no repair job should be irreversible. (All the glue used must be soluble.) Still, students can make mistakes. Dust, ink, or dirty fingers can stain pages; red-hot tools can set them aflame. Books infected with mildew or “foxing” (rust spots) need to be isolated properly from the rest.

And there are tricky questions to be addressed. What’s more critical: protection of the book or historical accuracy? Take specimens from the nineteenth century, the turning point in book publishing. Spurred by the new institution of compulsory education in France, the industrial-era presses cranked out machine-bound paperbacks. Do the surviving examples of such cheap, popular literature deserve the royal treatment? Or should they be left to rot in the attic?

Not all bookbinders are qualified to restore books. Students who complete Birlouez’s two-year program are only certified to do minor repairs. According to unesco guidelines, anyone under-taking to rescue a book dating from the sixteenth century or earlier – with its inevitably flaky parchment and crack-ed leather – requires a specialized six-year degree. (Next year, the atelier will inaugurate a program that will allow its graduates to assist a restorer with eighteenth-century books – no older.) Most students practice on books found at rummage sales, or on their own family heirlooms.

Birlouez emphasizes attention to detail, but she is also thinking on a grander scale. She’s forging alliances with other artisans, such as potters and cabinetmakers. She’s initiating student exchanges between her atelier and comparable programs in other countries. Her most ambitious plan is to found a European University of Book Arts and Crafts, which she expects, a decade from now, will be offering training to enough students to amass an entire army against the ravages of time.

Watching a bookbinder at work, it’s plain the act of recovery is more than tools and techniques; it’s a form of devotion, a prayer for the future. The mindset required for that process is as important to preserve as the techniques. By pursuing the craft, Birlouez’s students hope to find tranquillity. The patient humility of the bookbinder contrasts starkly with the modern state of mind, measured in frantic mouse clicks.

Alas, most of Birlouez’s days are taken up with modern concerns: phone calls, e-mails, and PowerPoint presentations. She networks, markets, plans, and proselytizes. The irony is not lost on her; indeed, it’s a source of some discomfort. “But, in order for others to continue this work, someone has to be an activist,” she says. In another five years, she hopes the future of her art – buttressed by educational programs and high professional standards – will be secure. Then, she’ll be able to retire to her country home, where her bookbinding workshop and her beloved tomes await