In a restaurant in Singapore’s Little India district I chatted recently with a man doling out bowls of fish-head curry. He called me a “mat saleh,” Malay for ‘white foreigner.’ He dubbed a woman who walked past us an “S.P.G.”—a ‘Sarong Party Girl.’ Upper-crust Singaporians who put on posh accents were “chiak kantang.” “Chiak” is Hokkien for ‘eating,’ “kantang” a mangling of the Malay for ‘potatoes.’ ‘Eating potatoes’: affecting Western mannerisms.

Singapore has four official tongues —Mandarin, English, Malay, and Tamil. At street level, though, none of these takes precedence. Neither does the Hokkien dialect, spoken by many older Chinese. The city-state’s functioning language is actually Singlish, a much-loved, much-frowned-upon hodge-podge of dialects and slang.

When the man asked if I could pay for the meal with a smaller bill, he expressed it this way: “Got, lah?” I recognized that bit of language cobbling. In Hong Kong, where I was then living, Cantonese speakers sprinkle their English with similar punctuation. ‘Lah’ often denotes a question, like ‘eh’ for Canadians. ‘Wah’ infers astonishment. Once, when I was walking through that city’s nightclub district with a Chinese friend, we nearly knocked into a Canto-pop star, a young man of smouldering Elvis looks. “Wah, now can die!” my friend said, only half-jokingly.

If English is the region’s default—neutral terrain for doing deals and making friends—loan words and hybrid street dialects advance its cause. It is the same across most of Asia. In the Philippines, Tagalog speakers refer to a look-alike as a “Xerox” and an out-dated fad as a “chapter.” “Golets,” they say, meaning ‘Let’s go.’ Anything first-rate in Bombay gets called “cheese,” from ‘chiz,’ the Hindi word for ‘object.’ In Japan, students on a Friday night announce “Let’s beer!” and salarymen quit smoking because of a “dokuto-sutoppu”—a ‘doctor-stop,’ or orders from their physician. The majority of these word constructions would be no more comprehensible to a North American than the latest slang out of England or Australia. They belong to the places that formed them.

All this activity marks an interesting point from which to examine the latest evidence surrounding the explosion of English, which now boasts 1.9 billion competent speakers worldwide. Ac-cording to the Montreal writer Mark Abley, author of Spoken Here: Travels Among Threatened Languages, “no other language has ever enjoyed the political, economic, cultural, and military power that now accompanies English.” English, he says, acts like a “brand name” and serves as a “repository of global ambition.” Describing a quiz given to young Malaysians that contained references to American culture, he reports: “The obvious theme is the United States. But the subtler theme, I think, is power.”

Mark Abley is far from alone in linking the spread of English with fears of a bland consumerist empire—i.e. with a certain vision of American might. Geoffrey Hull, an Australian linguist quoted in Spoken Here, advises the banning of un-subtitled English programming on TV in East Timor. “English,” he warns, “is a killer language.”

Such unease isn’t hard to understand. Of the 6,000 living languages, some ninety percent are at risk of vanishing before the end of this century. These are tongues spoken by fewer than 100,000 people, and rarely as the only means of communication. For some, the death of each marks the disappearance of a world view: Without a language to call one’s own, original stories stop being told and unique conversations with God diminish.

But is the link between the “tidal wave” of English, as Abley puts it, and the threat to variety so direct? English has long been viewed as a unique breed of barbarian. France’s civilisatrice and Germany’s kultur programs granted the colonial aggressions of those nations a patina of benevolence; not so with England. Over the past fifty years, as the U.S. has come to supplant Cruel Britannia as the primary ‘exporter’ of the tongue, it has come to bear most of the criticisms, too. When a Muslim group recently denounced the Arabic version of the Idol TV series because it “facilitates the culture of globalization led by America,” it didn’t matter that the program had originated in England. In certain minds, English can only ever be the language of McDonald’s and Nike, Madonna and Sly Stallone.

By this reasoning, English couldn’t form a natural part of Singaporian street life or Filipino cross-language talk. It couldn’t be the rightful possession of the millions of Indians who now call it their mother tongue. But the truth is, English isn’t just exploding across the universe; it is being exploded on contact with other societies and languages. It is, arguably, already the spokesperson for no single political power or region.

In Asia, at least, English feels this protean. The Hong Kong author Nury Vittachi has been charting the emergence of a pan–Southeast-Asian argot. He calls it ‘Englasian,’ the wonky dialect of international business types and youthful hipsters. Vittachi even penned a short play in Englasian called Don’t Stupid—Lah, Brudder.

Spend any time in the region and two things become obvious. First, English still makes only a minor noise, and only in the major cities. Its consumer blandishments pale against homegrown magazines, movies, and pop singers. No major Asian language, be it Mandarin, Malay, Japanese, or any of the fourteen principal Indian tongues, is at risk of vanishing. In fact, those languages are killing off their own sub-dialects and non-standard variants. The world is everywhere too connected for the health of the linguistically vulnerable.

The second observation relates to the playfulness of inventions like Singlish. If Asians are threatened by the growing presence of English, they are express-ing their fear in the strangest manner—by inviting the danger into their homes. Linguists praise a language for its capaci—ty to acquire and assimilate expressions from elsewhere. Such openness is taken as a sign of confidence and growth. By this measure, the principal languages of nearly half of humanity are prospering. English isn’t storming these cultures to wage war on them; the locals, certainly, aren’t under that impression. They view the language mostly as a tool, one they can manipulate, and perhaps even make their own.

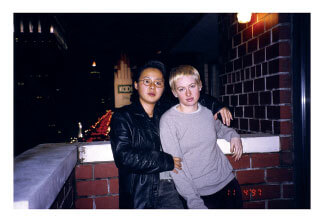

PHOTOGRAPHS: Speaking their language: From photographer Nikki S. Lee’s book Projects. For each project, Lee infiltrates a subculture over a period of weeks or months. She adapts her appearance—her hair and clothes—but also her speech, behaviour, and mannerisms, to blend into the group. These photographs of Lee, in her various guises, were taken by her new friends, with a point-and-shoot camera. ©Nikki s. Lee. Courtesy Leslie Tonkonow artworks + projects, new york