2017 Governor General’s Literary Award winners on the art of storytelling

The Walrus asked the 2017 Governor General’s Literary Award winners to answer a question— “What compelled you to tell this story?”—about their award-winning novels, plays, translations, and poetry.

The 2017 Governor General’s Literary Award winners are:

- Fiction:

We’ll All Be Burnt in Our Beds Some Night by Joel Thomas Hynes (St. John’s, Newfoundland)

HarperCollins Publishers - Poetry:

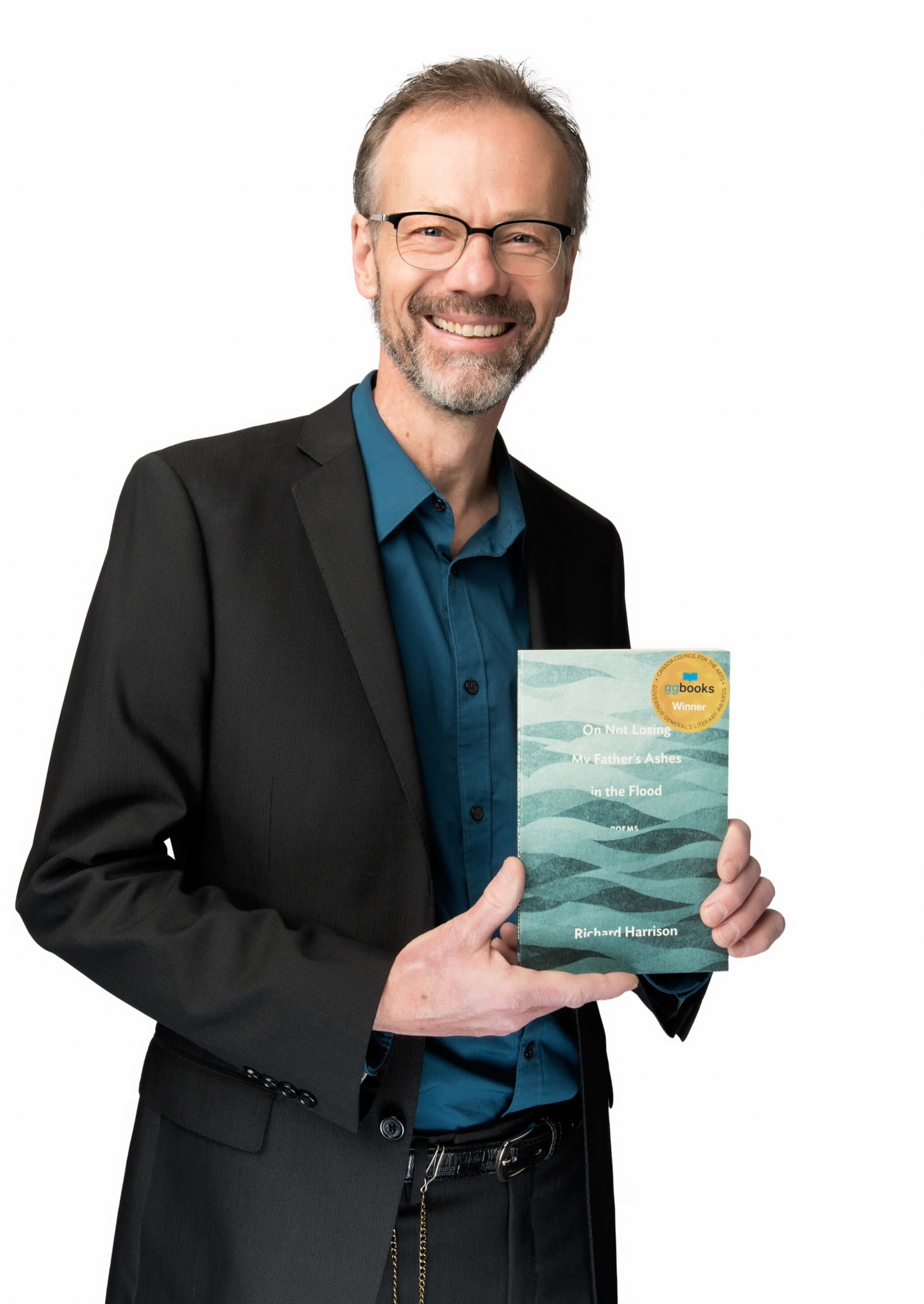

On Not Losing My Father’s Ashes in the Flood by Richard Harrison (Calgary, Alberta)

Buckrider Books / Wolsak and Wynn Publishers - Drama:

Indian Arm by Hiro Kanagawa (Port Moody, British Columbia)

Playwrights Canada Press - Non-fiction:

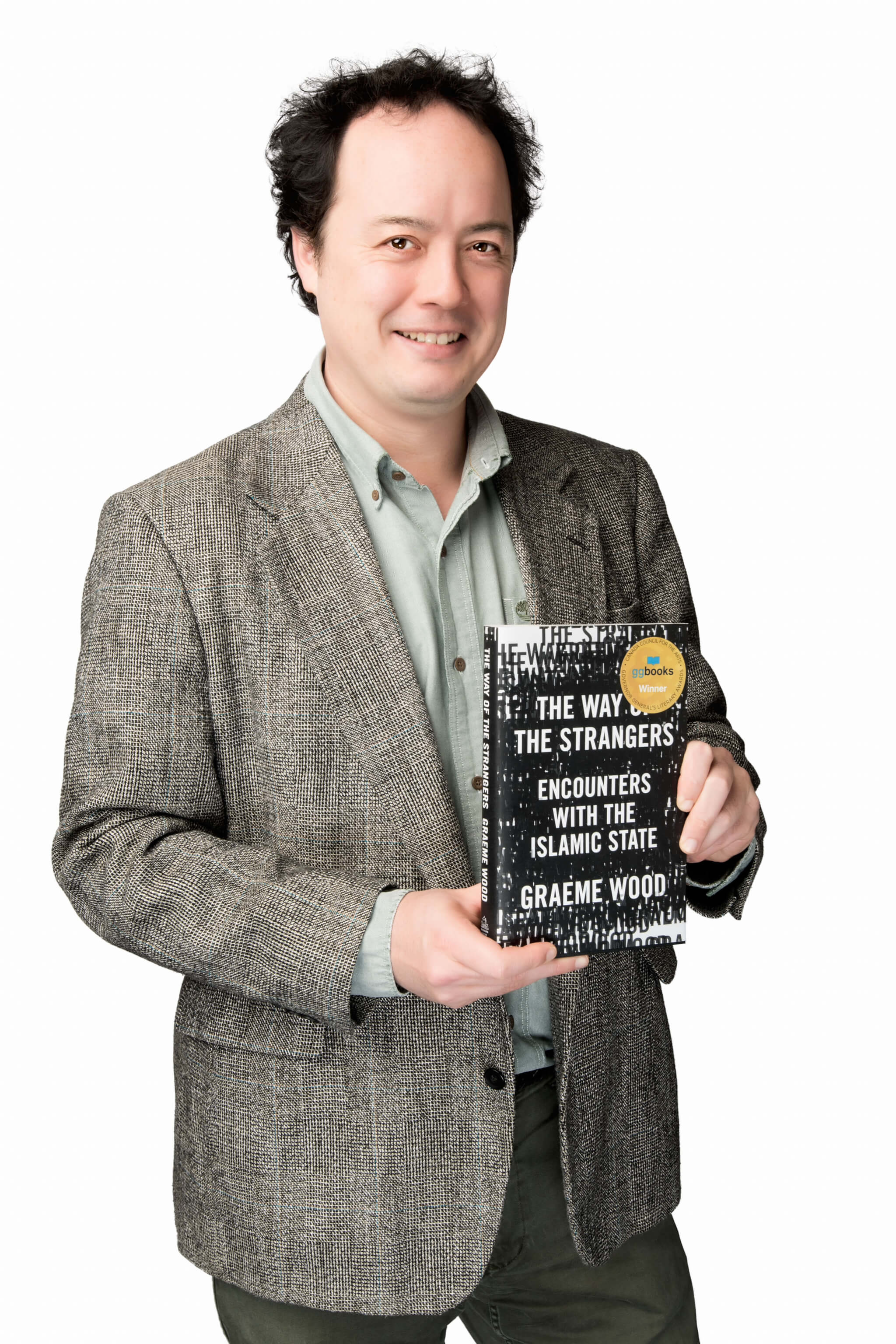

The Way of the Strangers: Encounters with the Islamic State by Graeme Wood (Connecticut, USA)

Random House / Penguin Random House - Young People’s Literature – Text:

The Marrow Thieves by Cherie Dimaline (Toronto, Ontario)

Dancing Cat Books / Cormorant Books - Young People’s Literature – Illustrated Books:

When We Were Alone by David Alexander Robertson and Julie Flett (Winnipeg / Vancouver)

HighWater Press - Translation (from French to English):

Readopolis translated by Oana Avasilichioaei (Montreal, Québec)

BookThug; translation of Lectodôme by Bertrand Laverdure, Le Quartanier

Q: What compelled you to tell this story?

Joel Hynes: I’m treading over old territory talking about this subject, but I have always been very interested in characters that dance around the peripheries of society. I have more of an appreciation for the underdog than the person who has had it handed to them their whole lives and fucked it up. I love stories of people who overcame great odds when the world was stacked against them—and I love very, very flawed protagonists.

I had also been wanting to write a road story, to stretch out geographically. Take a more regionally minded character and take him outside his comfort zone and see who he becomes. That’s what was interesting to me. Who are you when you don’t have the familiar? The idea I was working with [with Johnny, the main character in We’ll All be Burnt in Our Beds Some Night] was that the further and further he went from his geographical/spiritual home, the closer he could get to accepting and seeing himself and maybe forgiving himself for the man he’s become.

Q: What makes a good story?

Joel Hynes: I think when an author is very, very careful and considerate of the reader but at the same time isn’t giving a sweet fuck about the reader? There’s a fine line to tread in there.

As a writer, when you can walk away from a piece and interpret the story in one way and then have a conversation with a reader and they see it in a whole different light—in a way you didn’t intend or didn’t see. Compelling fiction does not spoon feed, and it’s not conscious of itself on the page. Doesn’t make it too hard, doesn’t make it too easy.

Richard Harrison

Q: What compelled you to tell this story?

Richard Harrison: Clearly part of my motivation to write poetry is just to write poetry—I love doing that. The poetic impulse for the book was a series of poems about different types of poems.

My love of poetry stems greatly from my father’s love of it. Whenever we would talk about things that were emotional, the poems would come out. The apocalyptic visions of Yeats, of the pastoral Dylan Thomas—that was the language that he would reach for to describe the most significant things in his life. And I carried that with me. He died in 2011 from vascular dementia, so the last ten years of his life were a slow diminishment of his memory, his capacities, and his physical self. And as he faded away, the last things to go were his poems.

The flood took a lot of things but also left a lot of things behind. It threw everything into chaos and then it left—and said, “Now you pick it all up.”

Q: What makes a good story?

Richard Harrison: It’s two things. One, it has to be the nature of the story itself, it has to be something I care about. But there also has to be a truth or point of view in the story that’s in language that I like. That’s probably where the move to poetry, instead of some other form, for me, exists. It has to be a language that has that cadence, that rhythm, that vocabulary, those sounds, those syllables that breathing method that I like.

I think the closer answer is that I’m really interested in getting that language down to the point where the story tells, in as detailed and intimate a way as possible, the truth as experienced from a given perspective. One tiny perspective. The paradox of it is, the poem that pleases me most looks like it was written by somebody else.

Q: What compelled you to tell this story?

Hiro Kanagawa: Stories and storytelling have been central to my life. So there is that aspect of it where I am a storyteller’s son and I love stories—I’ve studied them, [and] I’ve taught playwriting and a central focus of my class is narrative structure and the history of it. I really believe human beings are the storytelling ape, that it’s innate in us.

If you look at the cave paintings of pre-modern hominids, even petroglyphs, you can see that there is an innate desire to create narrative and to communicate stories to the others in your tribe. There is research done with very small children, less than a year old, and when researchers show them some series of events that has a narrative—a beginning, a middle, an end—and if you subvert the expectation of the narrative, even very small infants will react with astonishment. Stories are very important to us.

Q: But why this specific story?

Hiro Kanagawa: The story is an adaption of an Ibsen play called Little Eyolf, and the impetus came from the artistic producer of Rumble Theatre, Stephen Drover, who commissioned me.

Around that time, I had decided for myself that my mandate, my agenda as a writer, would be to write about the Canadian experience. I had decided I wanted to write Canadian stories, stories that were rooted in the Canadian experience and the region where I live, the lower mainland of BC.

I didn’t know how this 100-year-old Norwegian play would fit into my agenda, but then a couple of really cool things emerged—one was that Little Eyolf is set on the shores of a Norwegian fjord and right near where I live in Port Moody is Indian Arm, which happens to be a glacial fjord. The second thing was that the Tsleil-Waututh people, the First Nations people who claim Indian Arm as central to their traditional territory, they consider themselves the children of Takaya, which means “children of the wolf.” The wolf features very prominently in their mythology and their creation myths. And eyolf actually means wolf or “wolfy.”

With those two coincidences, I started to develop a story, a very Canadian story of my own, inspired by Little Eyolf, which involved Tsleil-Waututh characters and was set on the shores of Indian Arm.

Q: What makes a good story?

Hiro Kanagawa: What makes a good story is so different depending on the genre or the expectations of the audience and what any given storyteller is trying to achieve. And that’s what has been so interesting about meeting the other Governor General’s Award laureates—we all work in different genres. To speak with people who write children’s books, that form requires such economy in terms of using words and how you tell the story which is very different from writing a novel…and then playwriting is very different as well because all the narrative has to be conveyed through dialogue.

In my own case—I’ve taught narrative structure, so I do believe in that classical structure of beginning, middle, and end. And then the three things that I look for in my experience of story, especially in the theatre, are ritual, poetry, and transgression.

When I say ritual, I’m looking for it to take me back to that primal place where the earliest humans told stories about the scary things that were beyond the fire. I want that mythic element.

When I talk about poetry, I’m not talking about just beautiful words—I’m talking about a poetic sense of beauty and connectedness in the world. Storytelling compels us to be empathetic, to walk in someone else’s shoes, to understand how they’re feeling, to understand why they’re motivated to do the things that they do.

Finally, when I speak of transgression, for me personally, I enjoy it when a story is dangerous, when I feel like a story allows me to experience something I’m a little afraid of. I like feeling like I shouldn’t be reading this, I shouldn’t be seeing this. I’m not just talking about shock value. Because if you think about it, Greek tragedies where you have the gods and you have the mortals, that’s inherently transgressive because it transgresses the natural laws of nature. Human beings don’t ordinarily interact with the gods. It’s not just about stories that transgress the moral values of the day.

Stories take you somewhere—they allow you to travel to other spaces and times you ordinarily wouldn’t. All of these things are important to the human experience because they connect us.

Q: What compelled you to tell this story?

Graeme Wood: Islamic State militants were really stealing a lot of our attention. In mid-2014, in Canada and elsewhere, there was widespread confusion about why people would be doing this. And widespread disbelief—we wondered why there were dozens of people who were travelling from our country and tens of thousands travelling from others to go and leave everything behind to go to Iraq and Syria.

I wrote my book in part to remedy my own ignorance about what ISIS was and what ISIS was doing. That is the genesis of a lot of non-fiction writing—the discovery of something in the world that doesn’t match your priors, doesn’t match your expectations, and requires some analysis and exploration. There was a need, a market niche, and a kind of civic responsibility I had as a journalist to describe what this phenomenon was so we didn’t misunderstand it any longer than we had.

Q: What makes a good story?

Graeme Wood: Most of what I write is reported. Which means I gotta get out there and find information that I couldn’t figure out just from sitting around or playing on my laptop. And that’s related to what I think is one of the originating impulses of a good narrative, and that is starting with a mystery.

The first thing to start with is some deep and burning question that if you didn’t answer it once it was posed then the reader would be irate. You want to get the reader to a point where they’re as desperate as you are to answer whatever that original question is. The same impulse that propels that reporting, will, if it’s properly conveyed, propel the reader as well.

Q: What compelled you to tell this story?

Cherie Dimaline: The book started from a short story, and I was asked to write science fiction or speculative writing from an Indigenous viewpoint—to which I thought, “God, that’s so odd!” But I thought, “I’m going to do this, I’m going to think about what the future might be from an Indigenous perspective.”

So when I was thinking about the future, really what kept coming up was the past—this really tumultuous history that we’re still dealing with. We’re still in the midst of colonization, [and] we still live under the Indian Act. So I thought, “Okay, I’m going to take these issues from the past and move them very, very slightly into the future.”

For me, it’s the most important book that I’ve written, and it was really important that it be for young people, for Indigenous youth. I really desperately wanted them to see themselves in the future. We have a lot of issues in our community with suicide epidemics, so I thought, “I really want these kids to see themselves in the future and not just surviving but being heroes and being the answer.” And for non-Indigenous kids, I really wanted them to look at a potential future of residential schools and devastation of communities and think, “I would never let that happen.”

Q: What makes a good story?

Cherie Dimaline: I’m really lucky I was raised with my grandmother and her sisters and they were storytellers in our community. I was raised with the understanding that all of our history all of our teachings and all of our lessons are contained with stories—that a story is like a suitcase we carry our culture forward in.

I’m personally really interested in characters—what drives people and what their passions are. And the nuances emerge from there.

There’s something about a character who is really, really trying just to live. Living ferociously, living full out, doing whatever it takes to really feel and live completely in each moment. When I have characters that are doing that, that are just really living—it doesn’t have to be their best life, it can be a broken, messed-up life—but if they’re living as hard as they can, that’s what makes me love them and it makes me want to go on this journey with them.

Q: So character leads you to a good story?

Cherie Dimaline: With Indigenous storytelling, a lot of things come into play along the way. When I bring my characters there, when I talk about things that…come from our traditional stories, then I have responsibilities to those stories. There are some areas where I take liberties—certainly with the characters, I change geography—but when it comes to the traditional teachings, those are always unchanged.

Q: What are some elements of traditional storytelling?

Cherie Dimaline: There are a few traditional stories that I grew up with that are teaching tools. And there are some you can play with and there are other ones that have to remain the same, because we have to keep passing those along. For instance, certain stories you only tell at certain times of year. Winter is actually the time of the story. In the cold time, families and community stay inside and gather strength.

In my book, there is a Rugaru, a creature from Métis storytelling lore. He’s a dog that guards the road, and the lessons that the Rugaru carries are about keeping everyone in the community safe. You can change into a Rugaru in a few ways—one of the lessons for men is if you are not respectful of women you become this creature because you forgot your humanity, your responsibility as a man. The Rugaru is also an intermediary between the Indigenous community and the rest of the world—he often represents change and the return to community and the danger of falling out of step with your teachings.

Q: What compelled you to tell this story?

David Robertson: When I was reading the calls to action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and a few of them stuck out for me. One of them was that we needed to be teaching these histories, including residential-school history, as early as kindergarten….When I saw that, I was thinking about the books that had been published already about residential-school history, and I just felt like there was a gap—there weren’t a lot of books, if any, for kindergarten and grade-one-age kids. And, a lot of the inspiration from the book came from the survivors that I know—that I work with or I’ve met.

Q: Is what compels you different every time to tell stories? Is there a common thread?

David Robertson: They’re all about Indigenous peoples. What inspires me from book to book is usually the question “what gaps are there?”—what isn’t being done right now in literature? And what do teachers need? What are the resources they need to better reach and teach their students? It’s rare that I branch out in something that isn’t overtly trying to educate.

My overall goal is to create social change. I think where we start is with youth, and you do that through engaging youth and having them generate empathy for the history, the people that were affected by that history and the impact of that history. That’s really what drives me.

Q: What makes a good story?

David Robertson: I think about this a lot. To me what makes a good story is the characters within it. Whether you have an alien out in another reality somewhere or a little girl talking to her grandmother, if that character feels real, if their problems feel like something that somebody can relate to, if they’re speaking authentic dialogue, if they’re going to authentic emotions, that is what generates an attachment between the reader and the story.

If I get there, then I think kids growing up, those stories stick with them.

Q: What compelled you to tell this story?

Oana Avasilichioaei: It’s a novel, but it’s a novel in the way it’s a novel about novels. It’s a novel that undoes the novel as a genre. It has many forms and voices, including a dystopian, speculative novella in the middle of it. There’s a screenplay, there are all kinds of dialogues, including a Socratic dialogue, various epistolary parts—there are just a lot of genres and voices that have their own way of telling and their own kind of language. So from the point of view of a writer and as a translator, I found I was really compelled by the challenge of entering different kinds of voices and figuring how to recreate all those forms in English.

It is also, in a way, a semi-invented microcosm of the Québécois literary world. And this is a world that’s very little known to anglophone readers because it doesn’t get written about in English. So I think that it offers a small window into the creative landscape of Québécois thinking and literature and language.

Q: How do you decide what you want to translate? What makes a good story?

Oana Avasilichioaei: I also write myself, so it’s a little bit different when we’re talking about my own book projects versus the translations. I’ve been fairly lucky so far. I’m a literary translator, and the books I’ve translated have been books I’ve been interested in.

I’m really interested in how language creates thoughts and how one can keep pushing language to mean…so I’m really interested in work like that, that teaches me things about a language. It might be a compelling story, but if it’s not compellingly written, it’s not interesting to me.

These interviews have been edited and condensed for clarity.

About:

The Governor General’s Literary Awards recognize great Canadian books. Founded in 1936, the Governor General’s Literary Awards are one of Canada’s oldest and most prestigious literary awards programs. The Canada Council for the Arts has funded, administered, and promoted the awards since 1959.