Johnny is a walking hard drive: a courier-cum-USB-stick. Anxious clients pay to stash data in his head. He has no access to the data; the right password, spoken aloud, triggers “idiot/savant” mode—and gets him talking.

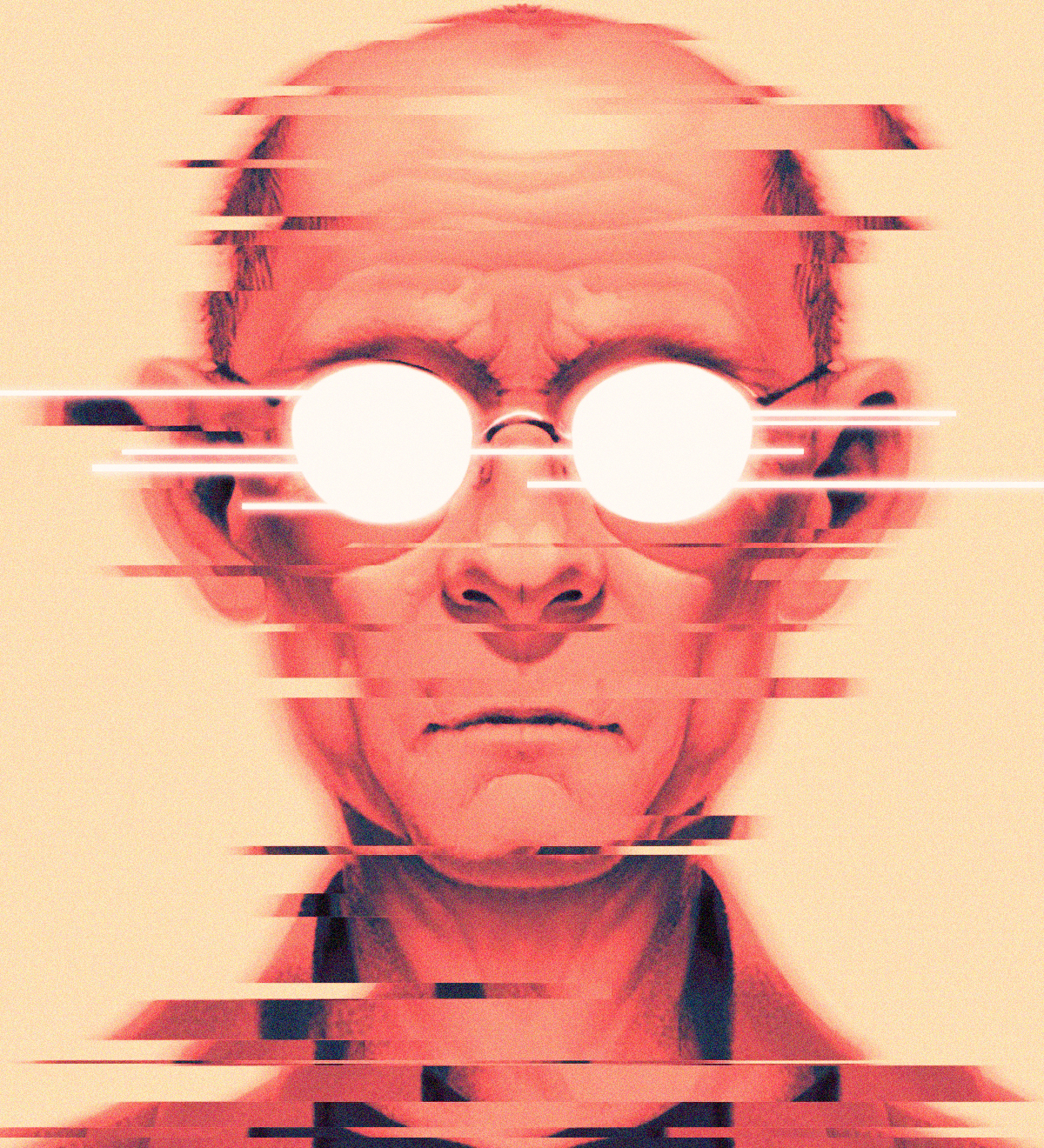

One day, Johnny discovers there’s a contract on his life. (Apparently, his head contains “hundreds of megabytes” pilfered from the Yakuza.) He falls in with a street tough named Molly Millions. Molly has mirrored lenses for eyes and keeps retractable scalpels beneath burgundy fingernails. A Yakuza assassin on their heels, Molly and Johnny eventually retreat to “Lo Tek” country, up in the rafters of one of the sprawling geodesic domes that span cities and their mushrooming subcultures.

It’s been four decades since William Gibson’s short story “Johnny Mnemonic” appeared in the May 1981 issue of Omni magazine. He’d already published a couple of pieces, but “Johnny” was a landmark feat of fiction: in a matter of eight magazine pages, Gibson roughed out the contours of an entire world.

The world Gibson was building was a wormhole away from most science fiction—from space-opera optimism and the sort of intergalactic intrigue that’s settled by laser sword. Gibson’s heroes were hustlers, their turf the congested city. They used substances, skirted the law, and self-edited via surgery (see Molly’s nails). He provided more detail, the following year, in the story “Burning Chrome,” which coined the term cyberspace: a boundless 3-D grid, “an abstract representation of the relationships between data systems”—a kind of web. And then, in 1984, he went even deeper with Neuromancer. His zeitgeist-rattling debut novel was about a hacker for hire who navigated cyberspace using a modem and an Ono-Sendai Cyberspace 7 deck, a Gibson confection that rests on his hacker’s lap (and sounds a lot like a modern-day laptop).

In time, the cyberspace coinage went viral the vintage way: it travelled from printed page to rapt fanboy. Neuromancer scooped up the available awards, generated two sequels, and popularized a sci-fi subgenre, “cyberpunk,” a nuisance term (see also “grunge” or “millennial”) that leapt from think piece to think piece like an augmented tick.

But Neuromancer was more than just an act of prescience that predicted something like the web. As Gibson himself has pointed out, the book was really about its moment. With conspicuous references to plastic surgery, the idle rich, and multinational corporations, the world of Neuromancer and its brethren, the so-called Sprawl novels, was a proxy for the decadent 1980s. In other words, Gibson was a serious writer prodding at the excesses of his present—and in brilliant prose to boot, prose that dared to reckon with the very grain of the environments it imagined. Gibson had spliced the DNA of realism into science fiction.

The Vancouver-based author went on to produce over a dozen books, help launch another subgenre (steampunk), inspire U2, and even trigger a fashion trend (the “normcore” aesthetic of the 2010s can convincingly be traced to the habits of a Gibson character who’s “allergic” to brands). But “Johnny Mnemonic” was the first broadcast of Gibson’s brilliance. Four decades on, telegraphing the style and concerns of the books to come, “Johnny Mnemonic” remains a bracing reminder that Gibson, more than a pop prophet, is one of our best writers.

For all its obsession with the future, science fiction ages quickly. Still, some of the prognostications of “Johnny Mnemonic” have held up. “We’re an information economy,” narrates Johnny at one point:

They teach you that in school. What they don’t tell you is that it’s impossible to move, to live, to operate at any level without leaving traces, bits, seemingly meaningless fragments of personal information. Fragments that can be retrieved, amplified.

Gibson didn’t quite predict cookies and social media, but “Johnny Mnemonic” nails our hermit-proofed paradigm. Even the story’s premise—that the most precious commodity is data—rhymes neatly with twenty-first-century anxieties about privacy and cryptocurrency.

And yet, the most radical thing about Gibson’s story is its realism. At the very beginning, Johnny delivers some tough-guy talk:

I put the shotgun in an Adidas bag and padded it out with four pairs of tennis socks, not my style at all, but that was what I was aiming for: If they think you’re crude, go technical; if they think you’re technical, go crude.

That Adidas bag was as stunning, in its day, as a phaser; sci-fi rarely deigned to mention such base details as brands. A year after the publication of “Johnny Mnemonic,” the movie Blade Runner posited a similarly radical (and radically banal) point in one of its most iconic scenes: the hover cars of the far-flung future, when they finally get aloft, will fling themselves past sky-high ads for Coca-Cola.

“Johnny Mnemonic” also reflects Gibson’s fascination with the cadged-together, a fixation, really, that runs through his work—from the artistic AI that remixes rubbish into dioramas in Count Zero to the squatter-occupied bridge in Virtual Light: a “patchwork carnival of scavenged surfaces.” Here’s a description of the ramshackle turf on which Lo Tek street fights unfold:

The Killing Floor was eight meters on a side. A giant had threaded steel cable back and forth through a junkyard and drawn it all taut. It creaked when it moved, and it moved constantly, swaying and bucking as the gathering Lo Teks arranged themselves on the shelf of plywood surrounding it. The wood was silver with age, polished with long use and deeply etched with initials, threats, declarations of passion.

When I tweeted once about the debris that fills his fiction, Gibson responded: “The mostly American sf I started with as a reader seldom got it that futures are built of pasts.” Gibson’s vision of tomorrow always keeps some clutter in view—“the chassis of a junked console” in Neuromancer, “the tattered yellow wall of National Geographics” in Virtual Light. (Actually, by my count, there are at least three such walls of shelved National Geographics in Gibson’s body of work; the denizens of his futures can’t seem to divest themselves of print media.) Debris provides density, a backdrop against which hi-def futures can properly pop.

Even that opening monologue of Johnny’s—“If they think you’re crude, go technical; if they think you’re technical, go crude”—reminds us that progress is a feint. To prep a shotgun, Johnny notes that he’d “had to turn both these twelve-gauge shells from brass stock, on a lathe, and then load them myself; I’d had to dig up an old microfiche with instructions for hand-loading cartridges.”

Gibson’s characters are often connoisseurs, preloaded with nostalgia streaks. There’s the brand expert in Pattern Recognition who covets her “fanatical museum-grade replica of a U.S. MA-1 flying jacket,” the work of “Japanese obsessives.” There’s the restless publicist in The Peripheral who longs for an artisanal past. Gibson himself once made a living as a “picker,” sourcing antiques for collectors. There may be no purer distillation of temporal tension in all of Gibson’s fiction than the tableau of Johnny and Molly “crouched in the narrow gap between a surgical boutique and an antique shop” as rain from a “ruptured geodesic” falls behind them.

The future shock of “Johnny Mnemonic”—including sharp details like “tooth-bud transplants from Dobermans”—is so distracting it’s easy to miss how graciously economical Gibson is; unremarked-upon references to “Mercedes electrics” and a “tendon stapler” pass by quickly, trusting their reader to fill in the rest.

There are certainly apprentice moments in “Johnny Mnemonic”: overwrought lines, the noir poetry of a novice. (See, for instance, “The Drome stank of biz, a metallic tang of nervous tension.”) But, for the most part, the story is delicately observed and pledges a fealty to physics and the implications of plot. When Molly, talking to Johnny, climbs up “through a hole in a sheet of corrugated plastic,” the sheet muffles her voice. And, when the Yakuza assassin removes his thumb tip and unspools a length of “monomolecular filament”—a wire the width of a molecule—the prose is precise and devastating:

Just a suggestion of a bow, and his left thumb falls off. It’s a conjuring trick. The thumb hangs suspended. Mirrors? Wires? And Ralfi stops, his back to us, dark crescents of sweat under the armpits of his pale summer suit. He knows. He must have known. And then the joke-shop thumbtip, heavy as lead, arcs out in a lightning yo-yo trick, and the invisible thread connecting it to the killer’s hand passes laterally through Ralfi’s skull, just above his eyebrows, whips up, and descends, slicing the pear-shaped torso diagonally from shoulder to rib cage. Cuts so fine that no blood flows until synapses misfire and the first tremors surrender the body to gravity.

Ralfi tumbled apart in a pink cloud of fluids, the three mismatched sections rolling forward onto the tiled pavement. In total silence.

The “conjuring trick,” the floating thumb, the body parts “rolling forward,” the “total silence”—Had Gibson somehow witnessed the results of an execution by invisible wire?

Panicking, Johnny discharges his shotgun. By this point, the reader may reasonably have forgotten that the shotgun is still sheathed in its Adidas bag. But Gibson hasn’t—and he takes pains to document the by-product: “I was covered in scorched white fluff. The tennis socks. The gym bag was a ragged plastic cuff around my wrist.” Fiction, let alone science fiction, is rarely as tactile as Gibson’s.

Later, after the Yakuza assassin slices off his own hand by mistake and falls through the Killing Floor, the principals rummage around for the hand. Says Johnny: “All we found was a graceful curve in one piece of rusted steel, where the molecule went through. Its edge was bright as new chrome.” That bright wound—reminding us that the new is ever present beneath the old, a gleam waiting to be revealed in rust—is as correct a detail as sci-fi has ever produced.

Perhaps Gibson’s genius, then, is taking the actions and reactions of his characters seriously. Over thirty years after the Yakuza assassin’s wire trick, in the 2014 novel The Peripheral, a magistrate of twenty-second-century London, Ainsley Lowbeer, produces a different sort of weapon, a shape-shifting baton that can summon a drone strike. A threat is near, and the weapon, a “tipstaff,” begins to

morph again, becoming a baroque, long-barreled gilt pistol, with fluted ivory grips, which Lowbeer lifted, aimed, and fired. There was an explosion, painfully loud, but from somewhere across the lower level, the pistol having made no sound at all. Then a ringing silence, in which could be heard an apparent rain of small objects, striking walls and flagstones. Someone began to scream.

“Bloody hell,” said Lowbeer, her tone one of concerned surprise, the pistol having become the tipstaff again.

The succession of double-take-inducing details is exquisitely managed. (It’s as if someone called in an airstrike on a rotary phone.) Gibson doesn’t explain how the tipstaff works or why it assumes the look of a “baroque” pistol; alert readers will get that tipstaffs are the products of nanotech and nostalgia, of advanced societies that have aestheticized how they do harm. A lesser writer, of course, would’ve insisted that the pistol do the firing, but Lowbeer’s ornamental weapon disgorges nothing, not a peep. The explosion is elsewhere, and Gibson is mindful that explosions have epilogues, the follow-up sound of raining objects “striking walls and flagstones. Someone began to scream.” Two chapters later, as wreckage is combed, we learn that the screaming belongs to a woman, physically uninjured. “‘See to her,’ he’d heard Lowbeer say, to someone unseen, ‘immediately.’” Lowbeer is concerned about trauma. It turns out that the magistrate never intended her drones to inflict so much damage; the approaching threat contained an explosive.

Maybe this doesn’t thrill you, but Gibson’s ability to release his characters into a scene and work out the logical (though not immediately obvious) impacts of their pinballing sets him far above most writers. It’s a rare quality, this knack for accounting. And it can’t be easily installed, slotted into a creative-writing student’s mind, say.

Like virtually everything that followed “Johnny Mnemonic,” The Peripheral also extended Gibson’s punditry, his habit of filleting the present with the edge of the future. Climate change and pandemics have wracked Lowbeer’s world, and Russian oligarchs loom. Even Lowbeer’s drones—the book calls them “flashbots”—quote our era’s impersonalized take on warfare. Gibson continues to iterate new futures to reskin our ever-shifting present.

Johnny and Molly decide to linger among the Lo Teks; characters in Gibson’s fictions often find their way into loose, makeshift communities. It’s a happy ending, though Neuromancer writes over it when Molly recounts Johnny’s inevitable darker fate. And a still-darker fate waited further on: a movie with Keanu Reeves and Dolph Lundgren, he of He-Man fame, reached the big screen (remember when screens were big?) in 1995 and duly flopped.

But the original 1981 story, which can be found at the very start of Burning Chrome, a collection of Gibson’s short fiction, has a deeper legacy. It created a world, sure, but a writer too. And, after all these years, it remains unforgettable, which merely means its sentences stay with you, as if they’ve been permanently uploaded.