ARTS & CULTURE / JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2024

What Should Canadian Museums Do about Their Stolen African Art?

Repatriation efforts were stymied for decades. But the problem can no longer be stalled

BY CONNOR GAREL

Published 6:30, Jan. 8, 2024

early-to-mid-sixteenth century, brass, 45 cm x 34.5 cm x 9 cmRoyal Ontario Museum, 908.66.1

Images courtesy of the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Canada. ©ROM

In the spring of 2022, beneath the dense cover of London’s interminably grey sky, two men slipped into the British Museum and headed for the basement. They were dressed in black, wearing hockey masks and carrying nylon bags, as if freshly defected from The Purge franchise. Though some unnerved patrons alerted security guards, nothing could really be done. When the men reached the windowless gallery that houses some of the world’s most famous collections of African art, they set about methodically stealing the treasures, one by one. They left through the front doors in broad daylight and emerged into the courtyard triumphant and untouched.

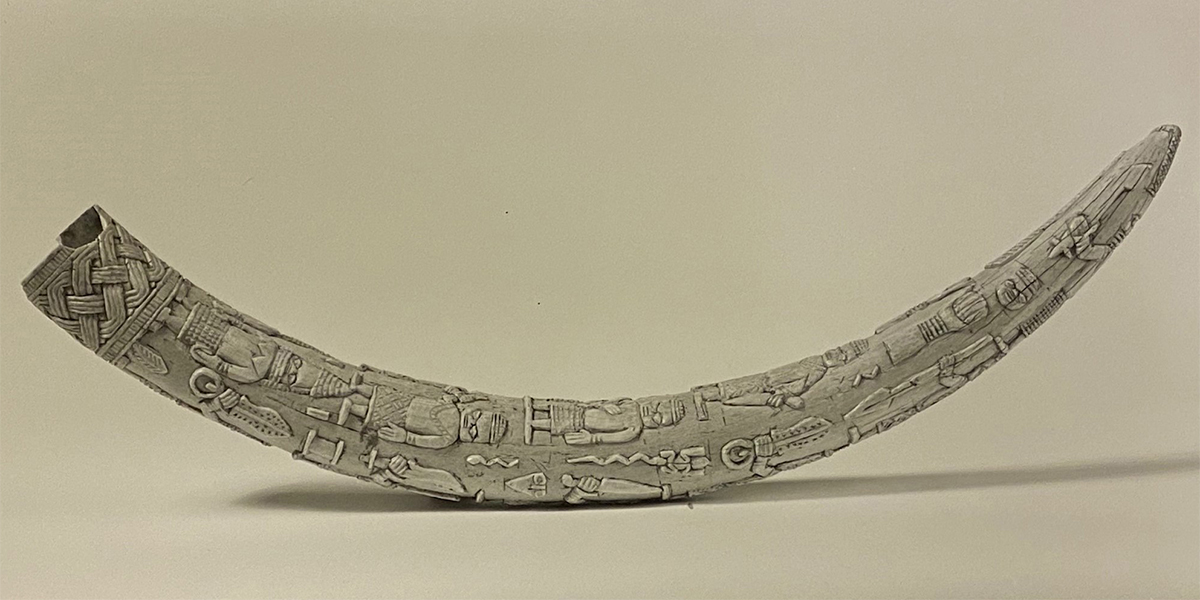

The targets of the operation were the famed Benin Bronzes, a group of sculptures that for centuries adorned the royal palace in the Kingdom of Benin, now located in present-day Nigeria. In 1897, British forces invaded the capital and massacred hundreds of Africans, exiled their leader, bagged everything that looked valuable, then razed the city, including the palace. The masterpieces they transported back to London included thousands of commemorative heads cast in brass, brass plaques, and intricately carved ivory sculptures. These were sacred records of the sovereignty, politics, and history of the Benin kingdom. The officers sold off or gave away many of the pieces upon their return home; these relics are today scattered globally across roughly 150 museums and galleries and some unknown number of private collections. A chunk remain in Britain.

Along with Greece’s Elgin Marbles, the Bronzes are the most visible symbol of the movement to return looted heritage to where it came from. The question raised by the caper at the British Museum, perhaps the world’s largest beneficiary of stolen art, was simple: If someone robs something from you and you choose to take it back, does it really constitute a crime?

The heist was the work of Chidirim Nwaubani and Ahmed Abokor, two men who lead Looty, a collective of activists engaged in the “digital restitution” of plundered artifacts. Using laser-scanning technology, the pair walked the length of the gallery and created 3D replicas of the Bronzes, to be accessed via the metaverse by their cultural heirs. “It’s unfortunate that Africans have to spend a fortune on visas, hotels, and plane tickets to see artifacts that should be down the road from where they live,” said Nwaubani. But Looty’s ambitions extend beyond the Bronzes. In March, they went back to the British Museum and used augmented reality to “re-loot” the Rosetta Stone, seized from Egypt over two centuries ago, and digitally return it to the northern port city of Rosetta, where it is thought to have been discovered. “I see Looty as a way of challenging the colonial hypocrisy of these dodgy institutions,” said Nwaubani.

Looty’s retributive fantasies have thus far focused solely on the spoils of British conquest. But if they wanted to expand the scope, to look abroad at the more discreet inheritors of such thefts, one place to start could be the third-floor African gallery at Toronto’s Royal Ontario Museum, where four Benin Bronzes are tucked inconspicuously behind a humidity-controlled vitrine: an ivory tusk carved with mythical images, a ceremonial waist pendant shaped like a mask, a cylindrical head cast from metal and wood, and a rectangular brass plaque depicting a young warrior in relief.

Until late 2022, when a roughly $2.3 million international research project called Digital Benin began publishing their locations, there was no comprehensive database of objects from the Kingdom of Benin, nor any centralized public information about how they ended up in places like the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, the University of British Columbia’s Museum of Anthropology, or the ROM. Historically, museums have not been so forthcoming about provenance records, which, on the whole, tend to be poorly preserved or incomplete.

Thanks to Digital Benin, which sourced images and information offered by 131 museums in twenty countries, we now know most of these Bronzes made their way into the North American art market sometime in the twentieth century. Many were purchased from auction houses or donated by families with blood ties to colonial-era troops who had served in Africa. In rare cases, there’s a paper trail. The ROM’s brass plaque, for example, was stolen from Benin in 1897 and purchased from a London art dealer in 1908; the tusk, removed from the altar of a high-ranking chief, was gifted in 1998 by the Braine family, whose relative had served in Nigeria in the nineteenth century.

And they are, plainly, still here: four objects with tawdry histories of extermination and dispossession. Why? What has undermined their return home? What has kept the “soul” of Africa, as Beninese president Patrice Talon once described his country’s cultural heritage, detained in white cube galleries, under dim lighting, devoid of the meaning that makes them sacred?

Calls for the return of looted African artifacts first gained prominence amid the dynamism and revolutionary spirit of the 1960s. At the time, African nations were gaining hard-won independence from colonial powers, and their ambitions for decolonization figured into a broader set of pan-African assertions: economic growth, political self-determination, and the chance to define themselves culturally, in part, by what was violently expropriated from them.

But for decades, all the impassioned African polemics, manifestos, feature films and documentaries, international committee meetings, and even United Nations resolutions on the matter fell on ears that refused to hear them. The shameful pattern that etched itself into the face of the art world became one of perpetual African requests and European dismissals. In her illuminating 2022 book Africa’s Struggle for Its Art, which chronologically reconstructs the origins of these battles, French art historian Bénédicte Savoy refers to this as a “history of postcolonial defeat”—a coordinated, bureaucratic counter-revolution by European museum professionals that succeeded, through subterfuge and stonewalling, in burying the debate until it all but “disappeared from collective memory” by the 1980s.

The portrait of lies and disinformation that Savoy paints is extraordinary. A former Nazi, moonlighting as a museum administrator, flat out lying about the provenance records of an acquired collection. French newspaper cartoonists mocking the belief that these treasures should be reunited with the communities that produced them. Curators arguing that Africans were “hardly sufficiently educated” to maintain the upkeep of a modern museum and that their art is far safer in European hands than it would be if shipped “back to the jungle.” The haunted tableau of barren rooms, fleeced of their art by feverish radicals, was constantly invoked by the press.

Eventually, the Enlightenment theory of the “universal museum” re-emerged. In 2002, the British Museum joined seventeen of the world’s leading museums to issue a statement that stolen artworks, over time, simply assimilate as “part of the heritage of the nations that house them.” Signatories included the Louvre in Paris, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and the Prado in Madrid, among others. They argued that art from Benin, along with other colonial objects, should be viewed “in the light of different sensitivities and values” that are “reflective of that earlier era” and that “to narrow the focus of museums whose collections are diverse and multi-faceted would therefore be a disservice to all visitors.” Though they weren’t part of the original group, years later, the National Gallery of Canada and the Art Gallery of Ontario quietly merged with its ranks.

We’ve since seen a tectonic shift in consciousness. It started in 2017, when French president Emmanuel Macron spoke on French-African relations during a state visit to Burkina Faso. His speech contained an explosive declaration: that he would, over the next five years, create the conditions under which Africa’s heritage could be temporarily or permanently restituted. The report he commissioned afterward, by Savoy and Felwine Sarr, a Senegalese economist, proposed a “new relational ethics” between France and African nations and found that at least 90,000 sub-Saharan African objects were held by French public museums, including, from Senegal, one anti-colonial military commander’s saber and, from Madagascar, the crown of Queen Ranavalona III, who was exiled with her family in 1897 following France’s annexation of the country. In fact, according to a UNESCO forum, between 90 and 95 percent of all African artifacts are currently in Western institutions. Europe has more African art than Africa itself.

early twentieth century, brass, 19.8 cm x 6.8 cm x 5.5 cmRoyal Ontario Museum, 971.165.509

Macron’s promises were perhaps disproportionate to what his country was prepared to deliver—a bit of dazzling political choreography to project an air of re-evaluating its imperial past. But the crawl of returns that followed was more movement than what the museum world had ever seen. After France gave back twenty-six artifacts to Benin, a handful of countries and their museums followed suit. Germany agreed to return 1,100 Bronzes to Nigeria and entered into negotiations on the restitution of artifacts to Cameroon, Namibia, and Tanzania. In Belgium, which has one of the largest collections of African art, a $2.9 million research program was established by the government in 2022 to determine the provenance of 84,000 colonial objects from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In America, the Smithsonian and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, among others, have made similar provenance pledges with regard to their archives.

This shift also fortifies what the Martinican poet Aimé Césaire once wrote in his 1950 polemical essay “Discourse on Colonialism,” where he argued that the museum itself was made possible by the destruction, pathologization, and fetishization of non-Western cultures—that it would have been better for Europe to allow those civilizations to “develop and fulfill themselves than to present for our admiration, duly labelled, their dead and scattered parts.”

And so we arrive at our present moment. Museum professionals publish scathing books that indict the very institutions that pay their salaries. The ethics of exhibiting plundered art are called into question by the public. Curators, struggling to answer questions about what they have in their collections, admit that they don’t actually know what they have or why they have it. The moment has cast an especially unforgiving light on the British Museum’s controversial deaccession policy, which restricts the board of trustees from returning objects unless they’re duplicates or damaged.

Whatever strategies of denial and deception prevailed in extinguishing the movement back in the 1980s won’t work this time. The problem can no longer be stalled or kicked down the road for the next generation to solve. The cultural debt collectors have rung the bell—again.

Canada, like your mousy, conflict-averse friend who absents themself at the onset of any uncomfortable situation, tends to fly well under the radar when it comes to the question of African repatriation.

This position is owed, in part, to recent data. In 2021, a report by Savoy found that our public museums currently house about 35,000 African artifacts (excluding what may be in private collections). These artifacts are mainly distributed between the ROM in Toronto (8,000 pieces), the Glenbow museum in Calgary (5,000), and the Museum of Anthropology at UBC (2,800). For context, that’s fewer items combined than what’s at the Weltmuseum Wien in Vienna, where a hall is now entitled “In the Shadow of Colonialism” and features interactive displays on which talking heads acknowledge the relations between so-called “universal museums” and the colonial project. Simply put, we just don’t have as much African art as other countries do.

Still, another reason for our inconspicuousness seems related to how we downplay colonialism and its afterlives within our borders, designating Canada a hero among imperial villains. Until the 1990s, in fact, the art world seemed content with the delusion that Canada’s distance from continental Europe safeguarded it from any plundered art at all.

This ethical lag crystallized in 1998, when the US government held a gruelling four-day conference in Washington, DC, where delegates from forty-four countries—as well as auction house representatives, art world professionals, members of NGOs—met to discuss, perhaps for the first time, what to do about the tens of thousands of Nazi-looted artworks floating around unchecked in museum collections. The systematic pillaging of Jewish property throughout the Second World War had led to what many consider one of the greatest cultural thefts in history: per the US National Archives, approximately one-fifth of all the art in Europe was stolen by the Nazis between 1933 and 1945. Fifty years later, no significant efforts had been made to reunite those artworks with their rightful owners.

The conference culminated in the establishment of the Washington Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art, a declaration of eleven non-binding recommendations. Among other things, the principles encouraged governments to identify all artworks with ambiguous Holocaust-era provenance, to publicize whatever they found in a central database, and to establish official processes to resolve any ownership issues.

Canada was among the dozens of countries that endorsed the principles. And in the aftermath, some major Canadian art museums started sifting through acquisitions for works with Nazi-tainted provenance. Curators and provenance researchers typically worked backward, beginning with the last time the artwork was shown and then tracking through auction records, accession files, dealers’ catalogues, and exhibition archives. A quarter century after that conference, the cracks in Canada’s approach have become apparent.

It’s been estimated that Canada’s tally of Nazi-confiscated art may run into the several thousands. But there’s still no national database, no further commitments to locate them, and no clear, government-defined policy for how to handle them once identified. Clarence Epstein, director of the Max Stern Art Restitution Project, says that our courts don’t classify looted art as the fruit of any legally defined “theft,” and so negotiations tend to happen outside the justice system, on a case-by-case basis.

If a museum wants to reject or dispute a request, little can be done. Only a handful of paintings have since been repatriated from Canada, including one seventeenth-century Flemish still life that the AGO formally deaccessioned in 2020 and that was possibly restituted to the wrong heirs. “There’s a strong willingness to do the right thing,” says Sara Angel, founder of the Art Canada Institute and an expert on Nazi-era art restitution. “But there isn’t a framework for how to do it.”

The issue is no less convoluted for Indigenous communities, qualified by the same budgetary shortfalls and political inertia that complicate provenance research for any other artworks. Indigenous communities are slowly beginning to recover some of the estimated 6.7 million cultural objects and the 2,500 human remains taken by missionaries, government agents, and anthropologists. Museum directors are scrambling to find the best path forward. In 2019, Liberal MP Bill Casey drafted a private member’s bill to develop a national repatriation strategy, and despite the unanimous support for it in the House of Commons, it died on the Senate floor due to the calling of an election. The existing process—fragmented, ad hoc—is insufficient and demonstrates Canada’s inability to back up all the endless government speak about “decolonization.”

Stephanie Danyluk, the senior manager of community engagement at the Canadian Museums Association, laments that it’s often difficult for Indigenous communities to navigate the obscure systems of each museum, to say nothing of how pricey it can be. “It’s more about Indigenous nations having the resources to support their own research, because that’s kind of where the force comes from—not from the museums,” she says. “They want their cultural belongings and ancestral remains back, but the amount of work that it takes on top of what they’re already needing to do is huge.”

According to a 2019 report by the Globe and Mail, the Haida Nation, over the course of three decades, had to spend upward of $1 million to recover the remains of over 500 ancestors from museum collections and universities. Their expenses included researching the location of the remains, negotiating with institutions, getting permits for reburial, the cost of the funerals, and covering travel costs for whoever accompanied the remains back home. There’s something abject about forcing Indigenous communities to pay to recover the bodies of stolen ancestors. It’s also a borrowed tactic, twisted to apply to human beings. In June 1980, after years of rejection, Nigeria was forced to spend half a million pounds to purchase back four objects with Benin kingdom provenance from a Sotheby’s auction in London. Good strategies die hard.

When artificats from Africa flooded the European market in the late-nineteenth century, nobody in the Western world seemed to think about them as anything other than “primitivist” expressions of an underdeveloped people. Ascendant theories of polygenism and scientific racism had left Europeans with little doubt that anything forged in Africa was both intellectually and biologically inferior, giving rise to touring ethnological exhibitions of “exotic populations” and lucrative human zoos. After the conquests and industrial-scale lootings of African nations, the fetishes extracted were absorbed into what became the shimmering European avant-garde—as if their only use was to inspire the likes of Picasso, Matisse, and Modigliani.

Artistic inspiration, like wealth, has often been built on the backs of Africans. And this mass dispersion of relics made it easy for Canadians to wander into museums and bask in the light of treasures once far beyond our national sphere of attention. These were no longer just artifacts; they had become fine art. David Frum, a former George W. Bush speechwriter, says as much in a 2022 story for The Atlantic, in which he simultaneously dismisses curatorial efforts for repatriation as a “ritual of self-purification through purgation” and also praises his parents, Barbara and Murray Frum, as being “[a]mong those engaged in the fight to recognize African art as art.” The highlights of their collection, reportedly one of the most significant private holdings of African art, can be viewed today at the AGO.

But the art-washing of looted artifacts has also aided in severing them from their origins, placing them in contexts they were never intended to be in. One significant collection of traditional African art, made up of approximately 600 objects from nineteen West African countries, was donated by the Canada-based Lang family to the Agnes Etherington Art Centre, at Queen’s University in Kingston, in 1984. At the time, it was the largest collection of African art held by any Canadian university. But the records for where the artifacts came from, like for so many African objects, were patchy and poorly documented, leaving the museum to focus primarily on descriptions of their physical size, material compositions, and places of origin.

The result is that the context provided for these artifacts relies on a superficial understanding of their value, like describing a film you just watched solely in terms of its camera angles and lighting tricks as opposed to what happened or how it made you feel. This past summer, the curator of the Lang collection herself admitted that the museum’s practices needed to respond anew to “a colonial past and to the gaps in our understanding.” It’s that logic that drove Digital Benin researchers to recontextualize stolen artifacts by collecting oral histories on elements of Benin history and culture and featuring them with the original captions.

Versions of this approach are happening elsewhere too. When Nuno Porto was appointed curator of the African and South American collections at UBC’s Museum of Anthropology in 2014, he began to reconsider the outmoded, inaccurate, or inadequate language employed to describe the museum’s roughly 5,000 objects of African provenance. In 2019, he secured a $95,000 grant from the school and started a two-year program that contributed to reclassifying the collections, which included adding cultural affiliations and designations in African languages.

Porto’s team was able to generate about 1,000 new descriptions. In some cases, the work prompted them to display certain items in new ways. But they also debated whether other items ought to be on display at all. The museum holds a collection of ere ibeji figures, for example—wooden carvings made by Yoruba peoples to honour and represent deceased twins. For reasons not entirely understood, the Yoruba have one of the highest incidences of twin births in the world, and they view twins both as extraordinary beings and as sharing a single soul. If a twin dies, the parents consult a divination priest to determine whether an ere ibeji is needed for the twin’s spirit.

These figures are regarded as actual physical bodies, and the mother will ritually bathe, dress, and nourish the wooden carving, sometimes carrying it around in a cloth wrapper. “We had a Nigerian Yoruba curator and artist come into the museum, and one of the first things she said was that we had lots of people in cases,” says Porto. “As a museum, we didn’t acquire these as humans. We acquired them as carvings. But at some point in their biography, they were considered real persons by the people who carved them. And so by exhibiting them, we are re-enacting the slave trade—putting people on display to be looked at.”

The anecdote offers one way to consider the limitations of the universal museum as a site of civilizational understanding. Without accurate, culturally specific contexts for the artifacts, can these institutions be meaningfully differentiated from the human zoos that once exoticized the flesh of Africans? It also illustrates the dilemma faced by curators when they find artifacts they aren’t sure about exhibiting but have no real way of returning. Porto says it would not really be possible to repatriate ere ibeji without a specific request as they do not have documentation of the families for whom these objects would have had personhood. While Bronzes can be repatriated to a nation, ere ibeji belonged and had importance to individual people.

The MOA ultimately chose to display ere ibeji in its exhibition Sankofa: African Routes, Canadian Roots. For the exhibition, the Nigerian Yoruba curator developed a display which contextualized ere ibeji in a home setting, alongside contemporary photographs of twins from a Nigerian artist. The message was clear. A museum doesn’t get to determine the story of an artifact. The culture does.

Even as the world begins to catch up to what postcolonial theorists and intellectuals have been saying since the mid-twentieth century, and even as the word “repatriation” casts off the panic that once enveloped it, the process itself remains anything but inevitable.

It’s taken decades to get here, and it may yet take many more to reach any resolution. Provenance research is expensive and time consuming and requires a wealth of technical expertise. In Canada, museum directors have no organized framework to guide them—or anywhere near the necessary funds to do it properly. Some of the larger museums, like the AGO, choose to publish information on their websites about any artworks with questionable provenance and then wait for the requests to come in. But all the old defences, at the very least, have finally revealed themselves to be the evasions they’ve always been. The vintage excuses are starting to feel vintage.

For now, a good dose of irony seems apt. The British Museum was recently rocked by a scandal. A prominent curator appears to have pocketed up to 2,000 treasures over the past several years and put a number of them up for sale on eBay—including, according to the Telegraph, a piece of ancient Roman jewellery with an estimated value of up to $90,000 that was listed for as little as $71. The inside job has called into question the main defences of the universal museum. How safe is the world’s cultural heritage, really, if one of the largest public museums in the world can lose thousands of artifacts without anyone noticing?

One expert on illicit antiquities trafficking breathlessly called this one of the worst thefts in modern history. The chair of the British Museum, relying on the honesty of antiquarians, is hoping to recover what was fleeced.