WHO WILL INHERIT THE EARTH?

A lesser-discussed casualty of the climate crisis are children’s rights—particularly for those who are already marginalized.

On the sixth day of November’s COP26 climate summit, the kids were not all right. Led by eighteen-year-old climate firebrand Greta Thunberg as part of her now-global Fridays for Future movement, young people bombarded the streets of Glasgow by the thousands—not only in an attempt to demand change from the assembly of world leaders, but to embody it. Already well-known for her blistering candour, Thunberg dismissed the summit as a mere “greenwash festival,” accusing business leaders of “actively creating loopholes and shaping frameworks to benefit themselves.”

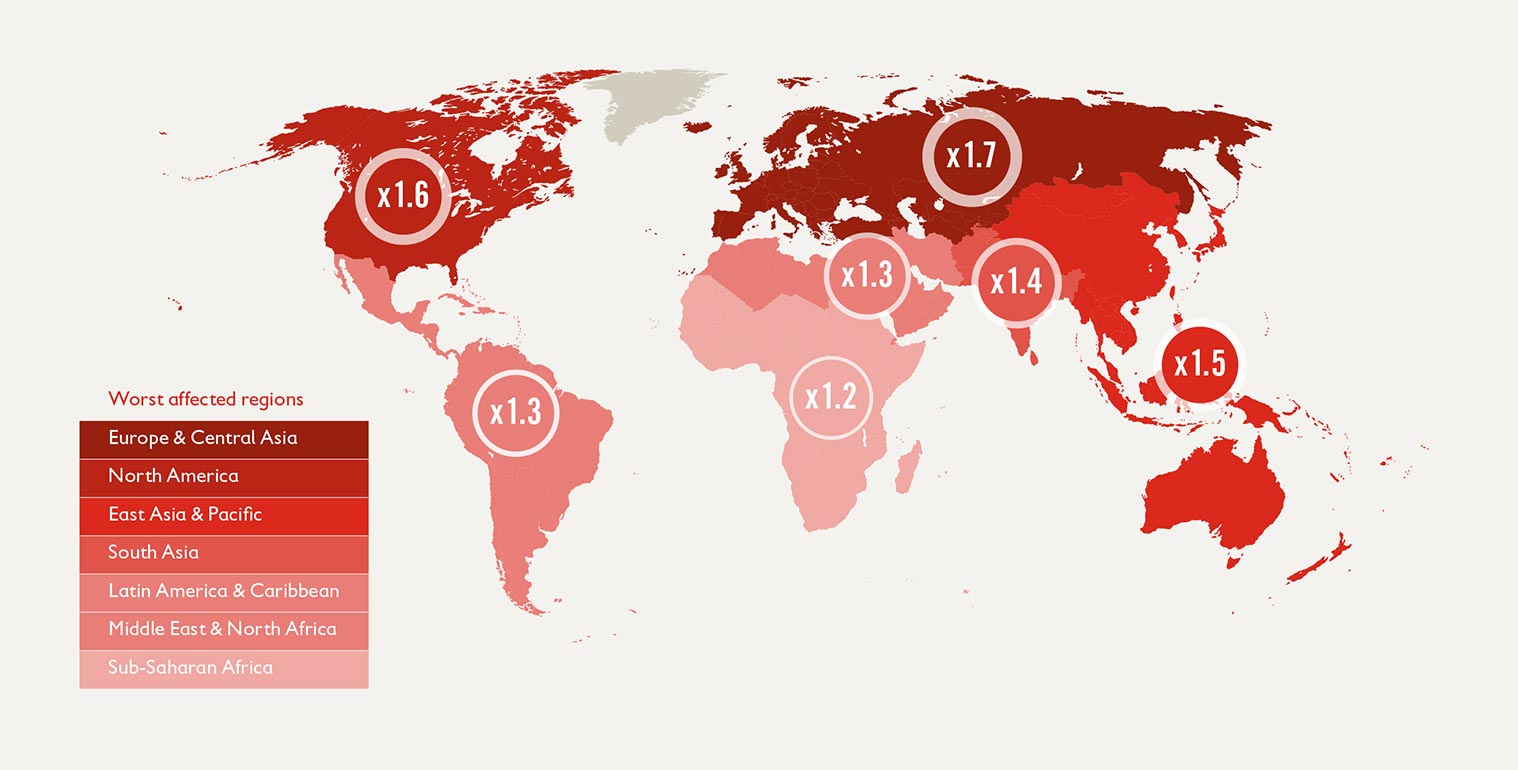

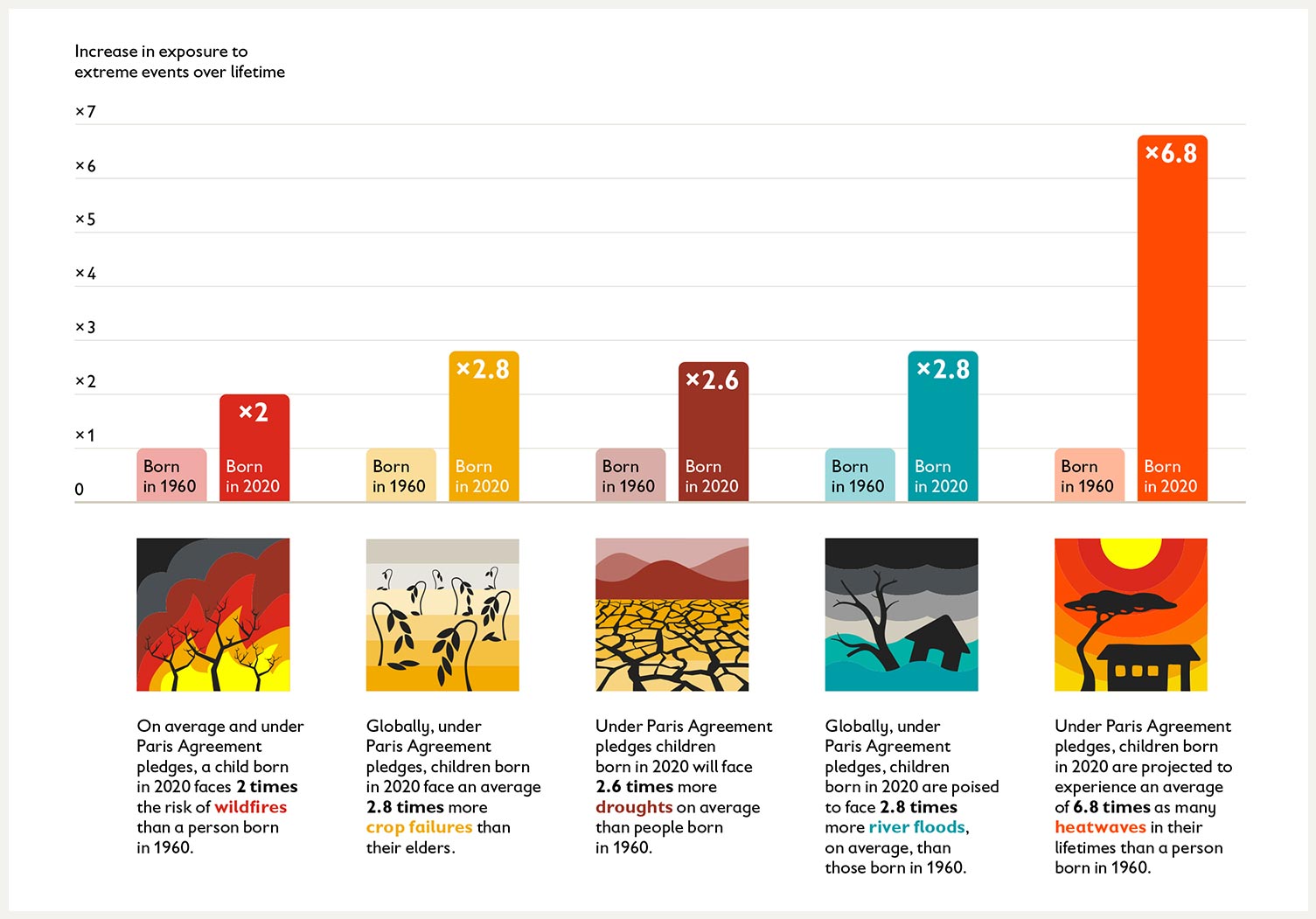

If you’re at all surprised to witness the vast mobilization of children and youth in response to our collective climate catastrophe, well, it’s their fight, too—perhaps more theirs than ours. Though they are routinely and conspicuously left out of conversations and high-level decision-making around environmental stewardship, according to Save the Children’s recent report, Born Into the Climate Crisis, climate change is “giving rise to an intergenerational child rights crisis.” Per research led by the Vrije Universiteit Brussel, a child born in 2020 will experience on average twice as many wildfires, 2.8 times the exposure to crop failure, 2.6 times as many drought events, 2.8 times as many river floods, and 6.8 times more heatwaves across their lifetime, compared to a person born in 1960.

Born into the Climate Crisis

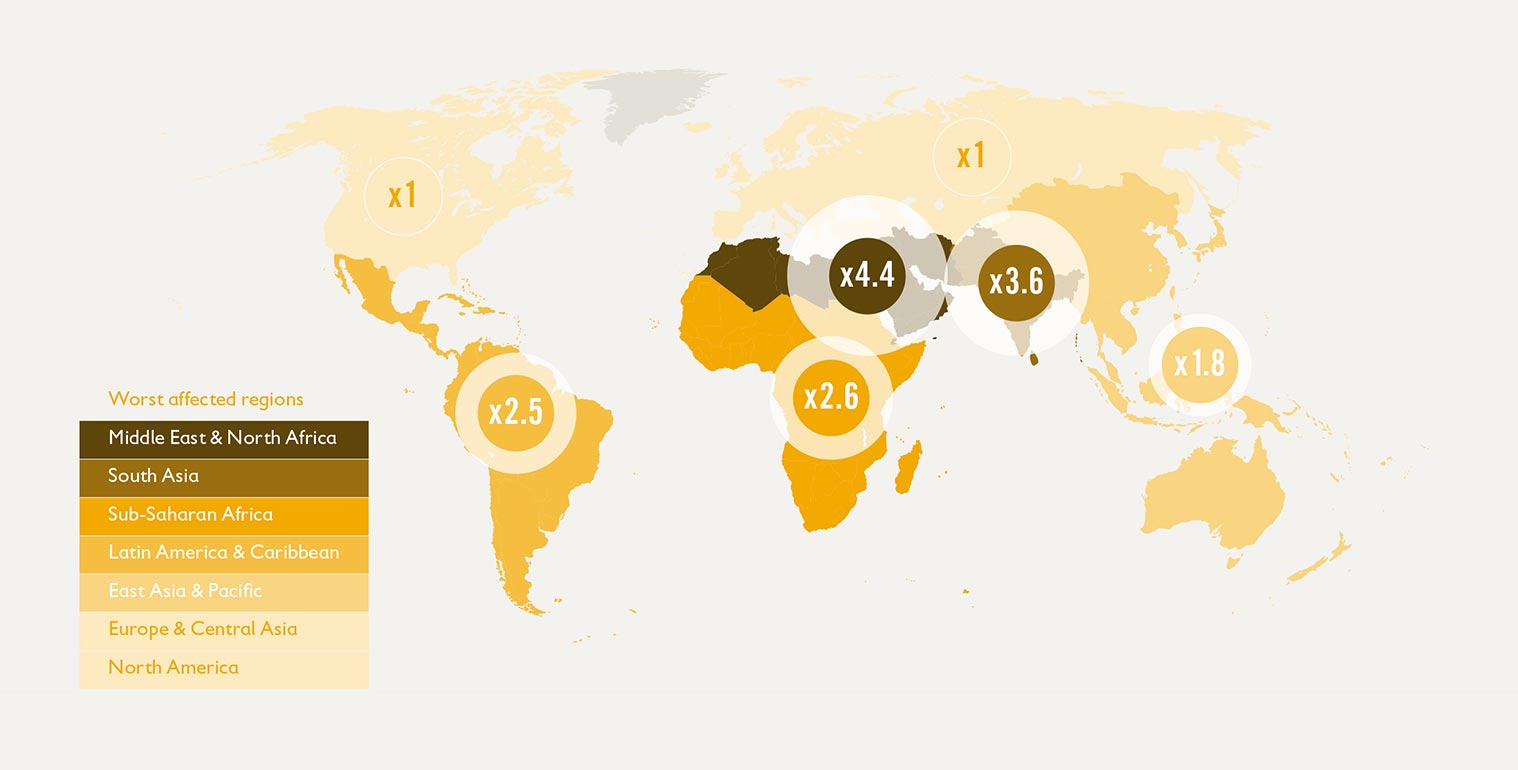

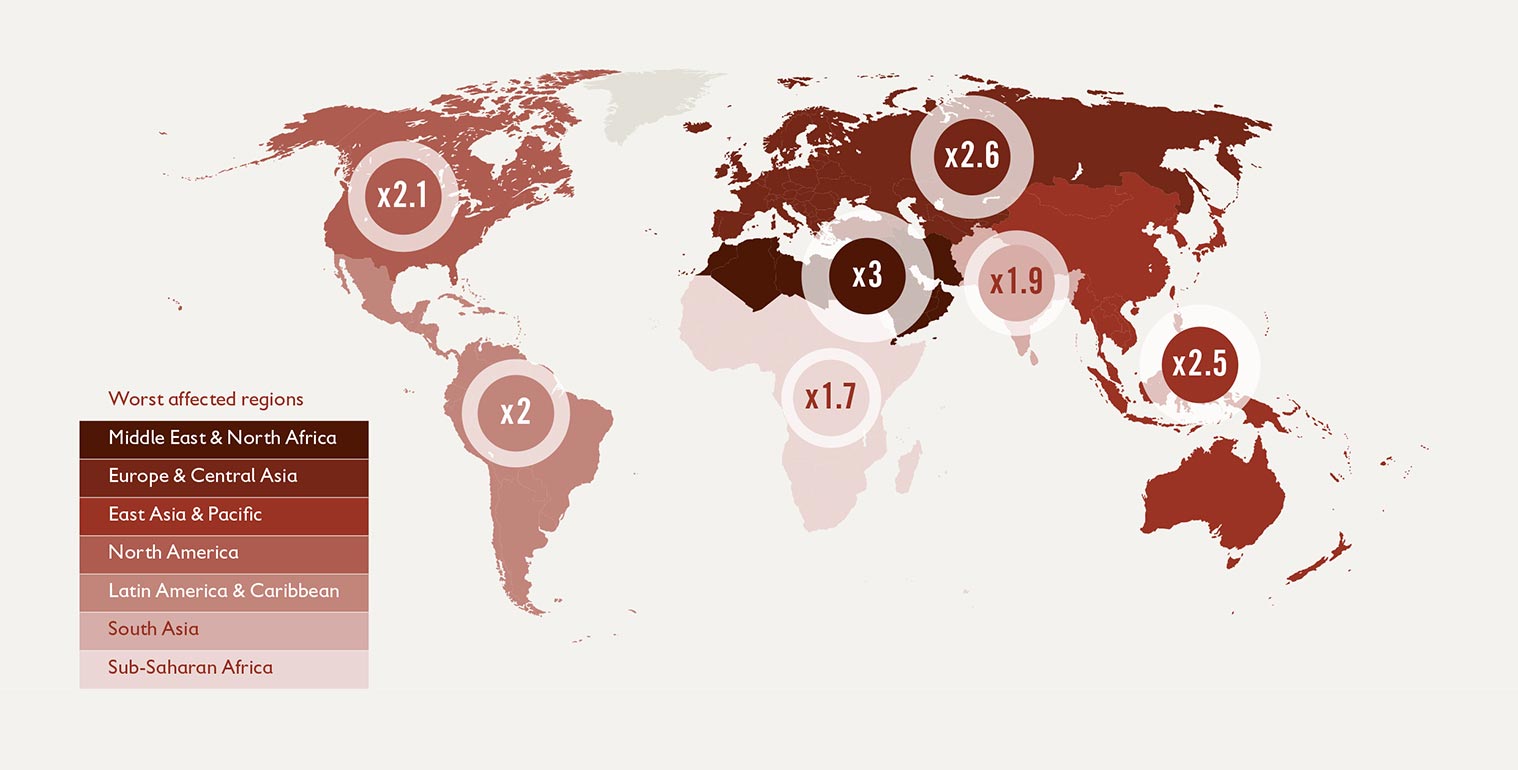

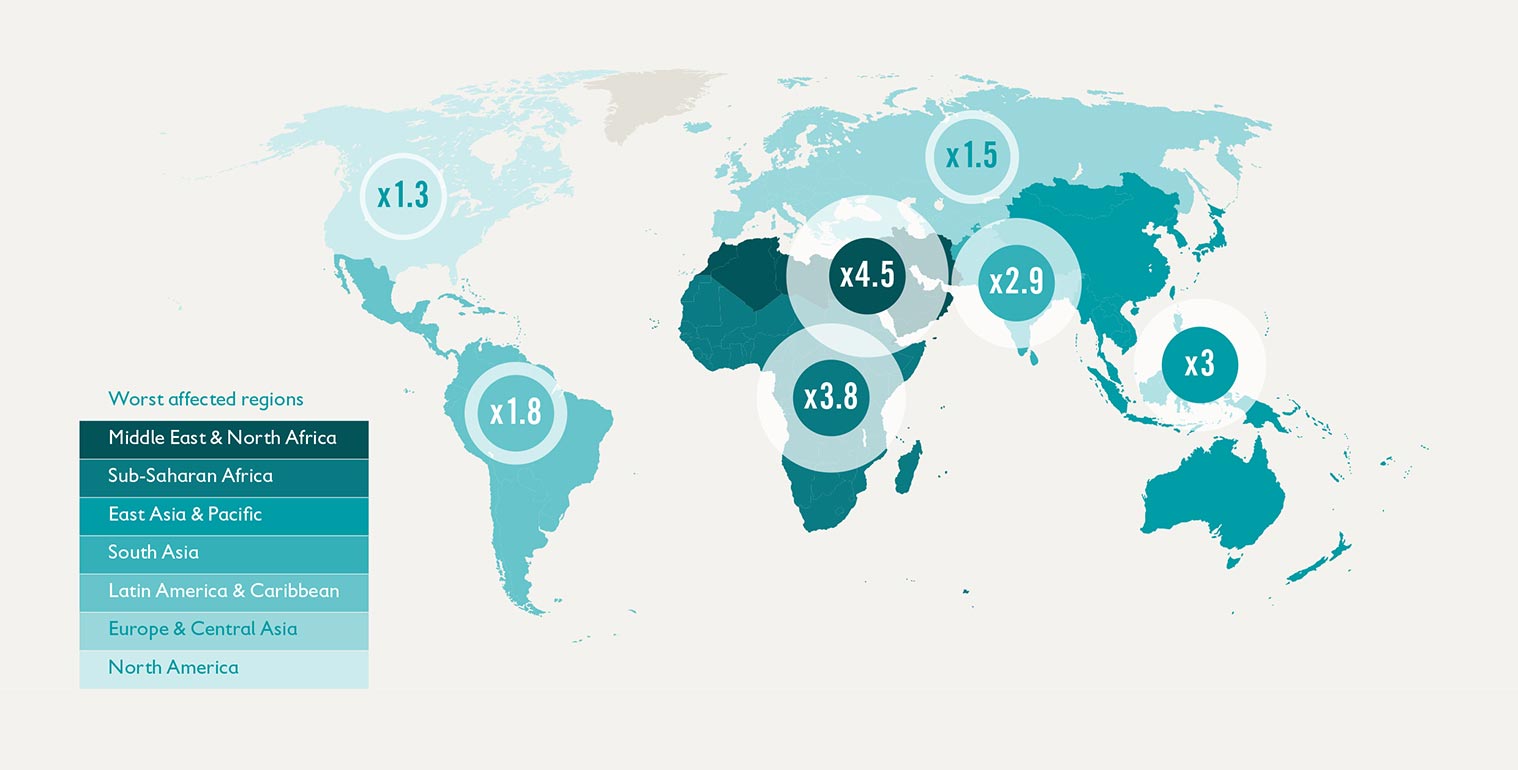

Lifetime exposure to extreme events for children born in 2020 compared to that of a person born in 1960.

But, by far, the most dangerous effects of temperature and weather volatility are endured by children living in low- to middle-income countries, particularly those who are already marginalized and discriminated against due to factors like gender, disability, displacement, and Indigeneity. (The problem isn’t exclusive to developing nations, either: First Nations communities in Canada are 28.7 times more likely to be internally displaced as a result of climate extremes and disasters than their off-reserve counterparts.)

For the already-vulnerable, climate change is often a compounded injustice, one that merits a hard look not only at which environmental issues are tabled and voiced, but also by whom. “If you look at some of the climate activism around the world,” says Danny Glenwright, President and CEO of Save the Children, “it’s children who recognize that this is the issue that will impact them for their entire lives, where maybe adults don’t. And it’s those who are already suffering from inequality that suffer first.”

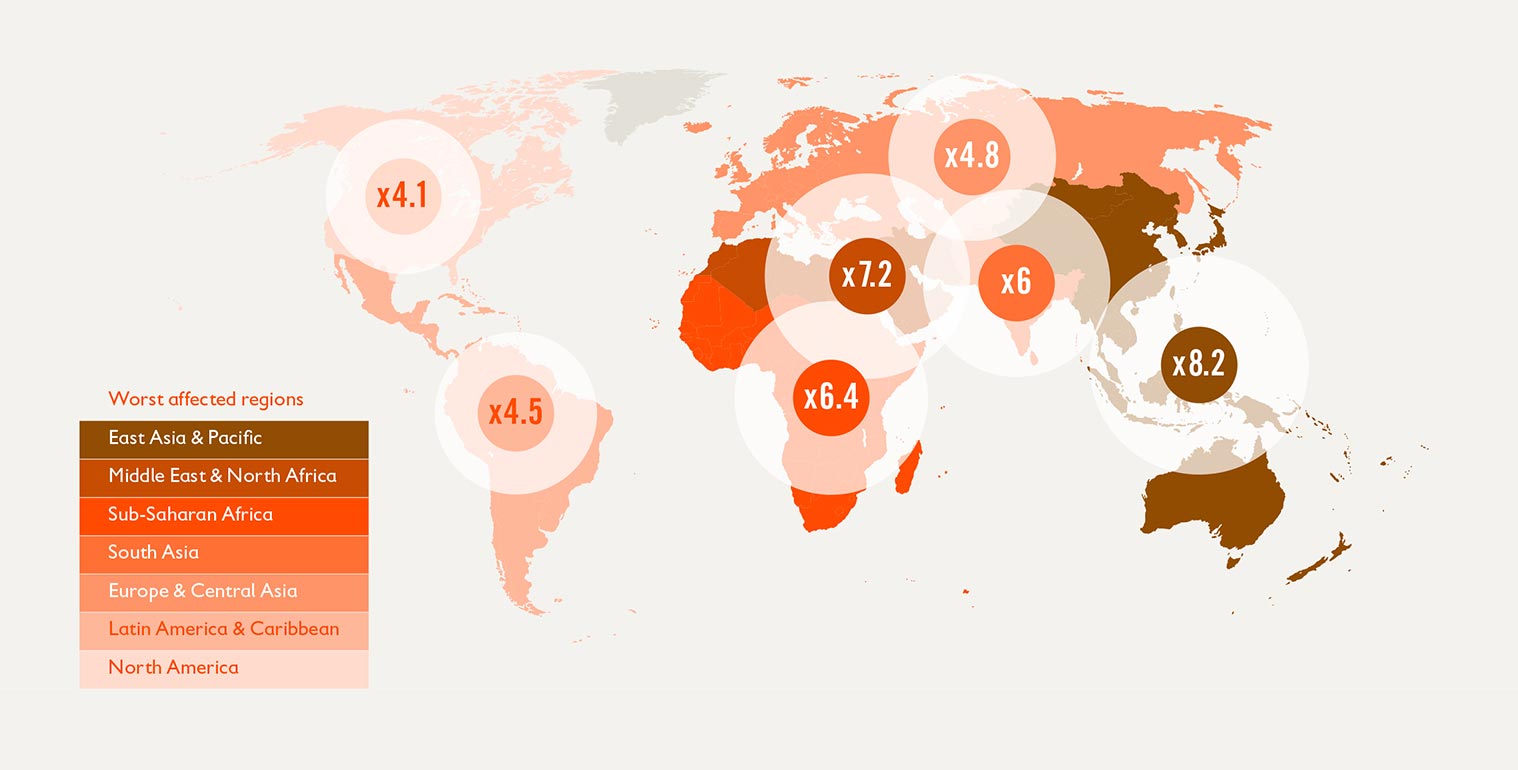

The Future for Children Around the World:

What the Data Says

The worst affected regions in lifetime exposure to extreme events for children born in 2020.

For Annabel Webb—a Canadian human rights practitioner, David Suzuki Fellow, and president and co-founder of Justice for Girls (a Canadian NGO that promotes the rights of teen girls living in poverty)—the need for child-sensitive action and an understanding of climate change’s myriad intersections hits close to home. Living in British Columbia, she’s borne witness to rolling wildfires and the struggles of her Indigenous neighbours—and their children—to engage in the cultural practice of seasonal fishing, which stocks their freezers through the winter months. But working abroad as an advocate for young women, Webb has seen plenty of evidence of climate change as a “threat multiplier.” “When there are climate-induced disasters, you see a spike in sexual and physical assaults of girls and women, or things like forced marriage,” says Webb. “If you take regions that are already stressed due to, say, decades of drought, and there’s already conflict brewing, [climate change] is like pouring gasoline on a fire.”

In the Sahel, a semiarid region of Africa that spans from Senegal to Sudan, the nexus of conflict, displacement, and food and water shortages has been disastrous for the progression of women’s rights: according to Save the Children, the region’s girls have been exposed to significantly higher rates of sexual violence than baseline, often experiencing assaults while walking far distances to gather safe drinking water. In what Glenwright calls a “negative coping strategy,” families in the Sahel have turned to marrying off their young daughters to make ends meet.

Take “Samira”, a fifteen-year-old student who—along with her family—was forced from her home in a village in Burkina Faso by armed men during a violent uprising. Fleeing to the nearby Yatenga province, Samira was out of school for the following two years. But her dedication to her education never wavered: she has since re-enrolled in her studies, and even taken on extra lessons to catch up with her peers, though the looming threat of early marriage is never far from her mind.

“Women and girls, historically, didn’t have many rights in these countries,” says Glenwright. “And they’re continuing to be eroded because of climate change, as families have less ability to eat and to pay for food. These tragedies are very real.”

For a problem with, as Webb says, “so many tentacles,” solutions must be similarly multifaceted. On the practical side, Save the Children issued its own child-sensitive recommendations prior to the COP26 summit: Canada must limit its warming to a maximum of 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels and ensure that the country’s financial commitment under the Paris Agreement ($5.3 billion over five years) includes social protections for children and families. For their part, the non-profit is engaged in bolstering climate resilience in some of the world’s hardest-hit areas by organizing on-the-ground programming that supports local agricultural practices, restoring habitats and, in some cases, providing cash grants to help families transition away from livelihoods rendered obsolete by climate fluctuations.

Their final recommendation, however, requires a political paradigm shift: recognizing children as equal stakeholders in the fight against climate change, and, in some cases, handing them the reins. “Children need to be at the decision-making tables, and I don’t mean as window dressing,” says Webb, who helped a group of teens, including her daughter (then thirteen), file a legal claim against the federal government, in part due to its continued investment in oil and gas. “Often the idea is that children don’t have the capacity to understand social policy, but in my experience, they are very, very quickly able to articulate the impact of climate change on them personally. They see the problem very clearly, and they’re not trying to please political masters. So they are extremely capable—if you give them a seat at the table.”

For all the questions of maturity, perhaps the clarity of youth—so expertly harnessed by Greta Thunberg and her peers—is exactly the kind of straight talk required to catalyze capitulating conversations around our most urgent collective crisis. “As an organization that supports and defends children’s rights, for us, it’s about standing with child activists, and creating forums for them to share their concerns,” says Glenwright. “In the case of the children that are suffering the most, some of them don’t even have access to electricity or food to eat, let alone access to media, so it’s difficult to hear their voices. But it’s critical. For them, it’s a black and white issue, and maybe it should be for adults as well.”