With stunted vegetation poking through its rough Precambrian ruins, Gereaux Island has a raw, windswept charm that holds up even on a sunny July morning. My journey to the tiny island from the marina at Britt—on the north shore of the Magnetawan River, sixty-five kilometres north of Parry Sound—took only a half-hour by boat. After fifteen minutes, however, the shoreline of suntanning cottagers, gazebos, and gas barbecues gave way to Georgian Bay’s open waters and random, lurking shoals. My first sight of the island was a postcard-perfect, red-shingled lighthouse on its granite roost. Then, as my boat chugged toward the wooden dock, three Pinus strobus in spread-eagled silhouette parallaxed into view: eastern white pines, the lofty kings of the boreal forest, and one of the reasons for my expedition.

Several days earlier, I had visited the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg, Ontario. Hanging on the walls of the gallery, famous for its Group of Seven collection, are dozens of paintings by Tom Thomson. In his hands, Canada’s northern woods reveal themselves in soft eruptions of colour: rubicund sunsets, splashy wildflowers, fire-swept hills, gusty shorelines. His robust brush strokes and thick spatterings of colour suggest the passion and determination of someone who has discovered his true subject, as well as the urgency of someone who feels he hasn’t much time to capture it—as indeed Thomson did not.

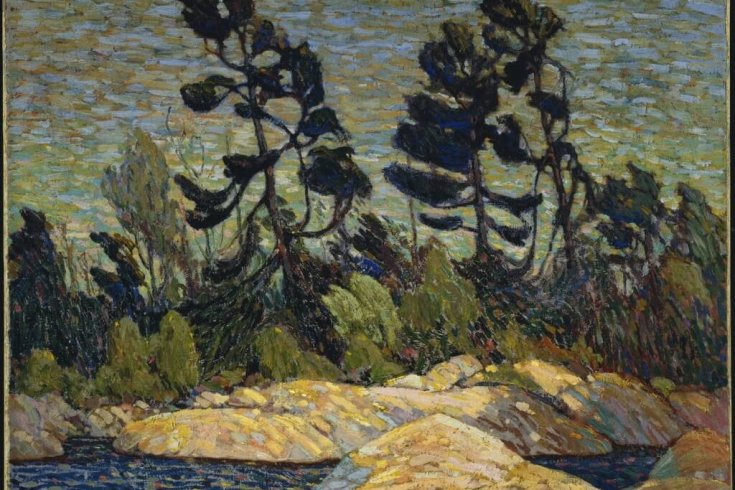

Even in this company, one painting compels attention. Begun in the wartime winter of 1914–15, it features three white pines arched against the sky, all flailing branches and straining trunks. Here, for virtually the first time in his career, Thomson turned the landscape of the Laurentian Shield into his distinctive icons of Canada. Before The West Wind and The Jack Pine, there was Byng Inlet, Georgian Bay. Thomson found at Byng Inlet not just the evocative subject matter he would so richly exploit until his tragic early death in 1917. He also developed his style, a thrilling mix of coruscating colour and energetic brushwork. Showing the audacious but controlled handling of pigment that was to become one of his hallmarks, Byng Inlet, Georgian Bay is a startlingly accomplished piece for someone who only two years earlier was little more than a Sunday-afternoon painter.

Thomson bloomed late. Born in 1877, he was thirty-seven and had achieved little with his brush by the time he painted Byng Inlet. But his shy blossoms, when they began to appear, were profuse and magnificent. In Byng Inlet, the boulders, water, and sky are all done in separate licks of paint, little hyphens of colour that fit together like the platelets of a mosaic, or the warp and weft of a multi-hued textile. This bold style owes little to photographic realism, and much to what the French neo-Impressionist Paul Signac called la touche divisée, the “divided touch.” Signac applied his pigments in separate, unmixed dabs, in the belief that the colours would spark off one another. “Make your colours as bright as possible,” he urged his followers. In the first decade of the twentieth century, Henri Matisse and the Fauves applied his theories with dazzling results (Matisse strove for a certain shade of red he believed could raise the blood pressure). In 1914, however, this colourful and expressive sort of paint slinging was still an almost unheard-of technique in Canada.

Standing in front of the McMichael’s Byng Inlet—something I’ve done many times over the past few years—I often thought that the geographical Byng Inlet should have a distinctive place in the Canadian imagination. Byng Inlet is a landmark not just for Thomson, but for Canadian art as a whole. It was the first time the white pine, sculpted by the prevailing wind into banner tree formation, was used as an artistic emblem (Canadian paintings were usually populated by more sedate-looking oaks and maples). The piece also indicates the existence in Toronto of a vibrant, determined modernism, at odds with the more placid, conventional landscapes by an earlier generation of Canadian painters, such as Homer Watson or Horatio Walker.

But Byng Inlet itself meant nothing to me. My Ontario Back Road Atlas revealed it to be somewhere off Highway 69, midway between Parry Sound and Sudbury, where the Magnetawan River flows into Georgian Bay. A black dot marked a town, likewise called Byng Inlet, on the south side of a swelling in the river. The black dot seemed optimistic, given that Byng Inlet features on two websites, Ontario Abandoned Places and Ontario Ghost Towns.

The enigma of Byng Inlet seemed an appropriate match for someone as confusing and contradictory as Thomson. He was a brilliant painter with little formal training. He was a loner who thrived in the atmosphere of a group. He was a self-described “wild man” of the bush who would cast off his mackinaw to don silk shirts and, when in funds, relish the niceties of city life. He was a powerful, courageous man rejected for service in the Canadian Expeditionary Force (or else he himself refused to enlist: the facts in the case are as contrary and obscure as so much else about his life). And, of course, he was an expert canoeist who, famously and unaccountably, drowned on a calm lake in broad daylight.

Sherrill Grace’s superb study Inventing Tom Thomson shows just how extensively Thomson pervades the Canadian psyche. He has been the subject of poems, films, songs, and even (most prolifically) conspiracy theories and murder-mystery fantasies. Even so, he remains an elusive figure. There is neither a catalogue raisonné of his work, nor a rich cache of letters that—like those of Cézanne or Van Gogh—might have revealed his artistic inspirations or the inner workings of his mind.

Anyone writing about Thomson therefore quickly runs up against his frustrating refusal to come into any kind of sharp biographical focus. I began to wonder if Byng Inlet, the place where he first began spreading his artistic wings, could reveal anything about him. Was there something about this remote northern settlement, apparently unviable and doomed, that caused his talent to begin its sudden, rich germination?

Opportunity came knocking in the form of an invitation from Peter Raymont and his colleagues at White Pine Pictures, whose name seemed happily propitious. They were in the midst of making a film with the working title West Wind: The Vision of Tom Thomson. Having hired a water taxi, they volunteered to help me ply the waters of Byng Inlet in search of those inspirational pines and Thomson’s lingering ghost.

Thomson loved the woods and waters of Northern Ontario, but Byng Inlet doesn’t seem to have been a considered or deliberate destination—more a chance meeting than a fixed appointment. For someone who grew up on a farm outside the pretty village of Leith, a stone’s throw from Owen Sound, he had strangely little enthusiasm for painting the Georgian Bay waterscape. The bay’s wind-whisked waters and corkscrewing trees inspired such National Gallery stalwarts as A.Y. Jackson’s Terre Sauvage, F.H. Varley’s Stormy Weather, Georgian Bay, and Arthur Lismer’s A September Gale, Georgian Bay. But Thomson always preferred Algonquin Park, which he visited for the first time, as far as anyone can tell, in the summer of 1912. The summer of 1914 was the first and only time he is known to have painted along the eastern shore of Georgian Bay—and Byng Inlet, Georgian Bay is the only significant painting of the area he completed.

Thomson arrived on this shore in late May of 1914. What drew him there was an eye specialist: his patron, Dr. James M. MacCallum, an ocular surgeon and a professor of ophthalmology at the University of Toronto. MacCallum didn’t know much about art (A. Y. Jackson claimed his appreciation was limited to finding animal shapes in Thomson’s paintings). But the distinguished oculist certainly knew what he liked, and Thomson’s paintings of the Ontario backcountry reminded him, he claimed, of his childhood on Georgian Bay.

Thomson was not a professional painter of any reputation when he first met MacCallum, at the end of 1913. For much of the previous decade, he had been a graphic artist, most recently at Grip Limited, the Toronto design firm where he worked alongside future Group of Seven members Lismer, Varley, J. E. H. MacDonald, Frank (later Franz) Johnston, and Franklin Carmichael. But at the end of 1913, he was liberated from the drudgery of designing posters and pamphlets when MacCallum, taken with a few samples of Thomson’s work, pledged to pay his expenses for a year as he established himself as an artist. It was a rare vote of confidence in a Canadian painter, at a time when most Toronto collectors bought Dutch and English art by the acre (as Jackson acerbically put it, “Art in Canada meant a cow or a windmill”).

Funded by MacCallum, Thomson settled into a regular pattern that would endure without deviation for the rest of his short life. The winter months he spent in his studio in Toronto, working on large canvases. The rest of the year, usually from April through October or November, he camped, fished, and painted at Canoe Lake in Algonquin Park. In the spring of 1914, undaunted by the snow on the ground, he pitched his pup tent beside an abandoned sawmill on the fringe of Mowat, the ghost town on the western edge of the park that became his base of operations. Toward the end of May, after a camping and canoeing expedition through the park with Lismer, he headed west to Georgian Bay when MacCallum offered him the use of his summer cottage.

The cottage, built in 1911, stood on a rocky island almost a mile off the mainland, at the southern end of Go Home Bay. Previous invitees included Lismer and MacDonald, both of whom duly produced shimmering waterscapes and distant panoramas of the neighbouring islands. Thomson, too, would execute a few oil sketches at the MacCallum cottage; he also gave painting lessons to MacCallum’s ten-year-old daughter, Helen. But the shy and introverted artist felt out of place in this world of Muskoka chairs and marshmallow roasts. As the extended families of other cottagers descended on Go Home Bay for their summer holidays, he began deploring the company as “too much like North Rosedale… all birthday cakes and water ice.”

Thomson would have been ill at ease in the Rosedale mansions and corporate boardrooms where many of his paintings now hang. In polite company, he came across as awkward and inarticulate. A former boss found him reticent to the point of bashfulness, and MacCallum called him “chary of words.” Even at Canoe Lake, where he seems to have been more relaxed than he was anywhere else, he developed a reputation as an eccentric and taciturn solitary. He sometimes studied the landscape with such intensity that he failed to notice when a friend greeted him. Even female courtesies were spurned. An attractive, well-bred young woman who expressed an interest in the “strange-looking chap” hunched over his paintings beside Canoe Lake couldn’t attract his attention. “I’ve spoken to him two or three times,” she explained in exasperation, “and he won’t as much as look my way or answer.”

Thomson needed peace and privacy to paint. Go Home Bay, colonized in such noisy abundance by Toronto’s social elite, provided neither. He wrote to Franklin Carmichael that he was unable to paint at the cottage, and it’s revealing that inspiration struck elsewhere, farther north, on a small, out-of-the-way island whose only inhabitants were a lighthouse keeper and his small family. Thomson had probably reached Georgian Bay and then navigated his way along its archipelago via a combination of train, packet steamer, and his own canoe. His progress was a leisurely one, and before arriving at the MacCallum cottage he spent a day or two on the Magnetawan River. He must have paddled his five-metre Chestnut canoe up and down Byng Inlet, probably trying to catch some of the muskie for which the waters were famous. At some point, as the inlet widened, he landed his canoe on an island, took out his box easel, and, crouching behind a sinuous stretch of rock, painted a small sketch, now in the Art Gallery of Ontario, that became the prototype for Byng Inlet, Georgian Bay.

If Byng Inlet is a ghost town, its ghost seems to be enjoying—during the summer months, at any rate—very rude health. In Thomson’s day, the settlement was divided by the Magnetawan River into Byng Inlet North and Byng Inlet South; today the former is called Britt, named a bit unromantically after the superintendent of the Canadian Pacific Railway’s Montreal fuelling depot. Both it and the town of Byng Inlet, on the south shore of the Magnetawan, are popular with boaters, cottagers, and kayakers. Wright’s Marina in Britt was doing a bustling trade when Peter Raymont arranged our two water taxis, with boats coming from as far away as Louisville, Kentucky. A mile upriver, where the river narrows to let the Trans-Canada across, a scene from an all-Canadian summer greeted us: young boys from the Magnetawan First Nation diving from smooth rocks into sun-sparkled water.

The Byng Inlet at which Thomson arrived in June 1914 was no ghost town either. It had a healthy year-round population of 1,200, and a book by local historian Fred Holmes depicts a thriving industrial town. Most of the men worked either at the CPR’s coal docks (opened in 1910 to supply the booming mines and paper mills of Northern Ontario) or for the local sawmill. This mill, one of Canada’s largest, was run by a tycoon aptly named William E. Bigwood.

Byng Inlet boasted all the amenities of a company town: a school, two churches, a dance hall, a billiards room, a jail, a bakery, a movie theatre, a steamboat landing, and a hotel. The wooden-sidewalked streets bore optimistic names like Rosedale and Klondyke. In summer, canoes and skiffs bobbed along the wide stretch of river. In winter, hockey games were contested on the two ice rinks, with old CPR boxcars serving as change rooms. American tourists bent on hunting and fishing arrived from as far away as Pittsburgh. Hard times came only later, in 1927, when the mill closed, and then in the 1950s when the coal docks shut down. As the rest of Canada was growing steadily bigger, Byng Inlet began to shrink rapidly.

Thomson must have felt more at home among these people than he had at Go Home Bay. Reading Holmes’s The History of Byng Inlet and Its Shoreline Communities, I couldn’t help but admire the long-gone Canadians pictured in its pages. To make a living in this hardscrabble landscape called for the kind of thrift, grit, and graft that few of us today have experienced or can truly imagine. With the coast guard’s inflatable lifeboat now patrolling the small-craft channel, with radio masts and a radar dome overlooking the RV-crammed Trans-Canada a few miles to the east, and with the Mint Julep (the yacht from Louisville) docked at the marina, it’s hard to imagine just how isolated and dangerous the town would have been a century ago, especially before the railroad arrived in 1908; or in winter, when for months at a stretch the steamboats couldn’t enter the inlet. Holmes offers a poignant litany of the town’s numerous tragedies: drownings, shipwrecks, sundry fires, people freezing to death or being struck by trains. One disaster seemed to encapsulate the pluck and the hardships in this part of Ontario: in the 1880s, a teacher drowned when she broke through the ice while skating home from school.

These adversities are a reminder that the Precambrian hinterlands painted by Thomson were more indomitable and inimical than those in Europe and most parts of the United States. In Canada, after all, people used to run rope lines from their back doors to their outhouses so they didn’t get lost in a blizzard and freeze to death while answering nature’s call. Given these perils, the Canadian response to the landscape was bound to be different from that of Europeans or even Americans. In 1943, Northrop Frye noted that much Canadian poetry evoked a “stark terror” in the face of a vast and hostile nature—the terror that Margaret Atwood, three decades later, catalogued with such verve and wit in Survival.

There was, though, little terror or menace in Canadian landscape painting in the days before Thomson and the Group of Seven arrived in the Ontario northlands. An earlier generation of Canadian painters had stuck to the country’s more pastoral regions, producing comfortingly nostalgic motifs of snake fences, grazing cows, and doddering barns. Horatio Walker, whose works breathed the terroir of the Île d’Orléans, summed up his artistic aspirations as the “pastoral life of the people of our countryside… the poetry, the easy joys, the hard daily work of rural life, the sylvan beauty in which is spent the peaceable life of the habitant.”

There was, I suspect, little easy joy or sylvan beauty in places like Byng Inlet—and that, for Thomson and the Group of Seven, was precisely the appeal of the northern woods. Despite their pretensions after their formation in 1920 to being a “national school,” the Group of Seven disdained Canada’s fertile agricultural lands (it’s ironic that Lawren Harris never painted the wheat fields combed by his family’s reapers and binders, and not a single member of the group ever painted a Saskatchewan landscape). It was to Canada’s Precambrian Shield—eerie, dangerous, hostile, often ugly, apparently untamed and unpopulated, and made accessible only by the railroad, waterways, and logging roads—that Thomson and the Group of Seven turned to create their avant-garde images of Canada.

The rural, remote Shield country might seem an unlikely proving ground for an avant-garde style of art. Most of us probably think of modernism as a metropolitan phenomenon, a response to fast-paced crowds, urban congestion, and social dislocation—not as something that happened around sawmills or beaver dams. Yet modernism had its rural side. Some of its greatest pioneers rejected the city for remote, “primitive” locations that provided them with a new artistic vocabulary. “I am finished with all that is not simple,” Vincent Van Gogh wrote to his brother, Theo, in 1883. “I don’t want the city any longer, I want the country.” And so off he went to paint the swirling skies and flamboyant cypresses of rural Provence. His friend Paul Gauguin, likewise in flight from civilization, left Paris to paint in Brittany and, ultimately, Tahiti. A few years later, the radical advances of cubism evolved far from the madding crowd, as Georges Braque painted his proto-cubist landscapes in the rugged French coastal town of L’Estaque (also one of Cézanne’s favourite haunts), and Picasso, a year later, in the Spanish hilltop village of Horta de Sant Joan.

Around the turn of the twentieth century, in other words, modern art was propelled forward by artists tackling raw landscapes in far-flung peripheries. Thomson and his friends were well aware of these developments. Jackson (who spent much of his time studying in France between 1907 and 1913) claimed in 1921 that the “gods” of the Group of Seven were “Cézanne, Van Gogh, and other moderns.” Appeals to nationalism shouldn’t disguise the fact that the Canadian painters were a combination of the backwoods and the boulevards—a mixture of mackinaw and Matisse. The elephantine boulders and whirligig pines of Northern Ontario, as well as its dazzling splashes of autumn colour, would be the building blocks of their own artistic experimentation—the Canadian equivalents of Van Gogh’s gnarled vineyards, or the Olympian presence of Cézanne’s Mont Sainte-Victoire.

For the Canadian painters, this escape to the country did, of course, take a detour through nationalism. They believed that by heading into the bush they were leaving behind an older, European civilization and discovering a more authentic—and more distinctively Canadian—world of nature. If the pastoral latitudes of Walker and Watson differed little from those painted by Europeans such as Millet or Constable, the granite cliffs and krummholz-formation pine trees of Ontario’s boreal forest seemed more singularly, undeniably Canadian. But the painters’ ability to capture these elements on canvas owed as much to the ateliers of Europe as it did to their canoe and snowshoe expeditions into Shield country.

Fred holmes’s book contains numerous photographs of Byng Inlet’s bygone industries: the CPR’s cranes rising like miniature Eiffel Towers above the coal docks; the intricate tramways and phallic-looking refuse burner of Bigwood’s sawmill. But Thomson had no interest in painting these sights. Instead, he must have climbed into his canoe and paddled downstream along the inlet to where the Magnetawan flung itself open to Georgian Bay.

My plan was to find the spot where Thomson had produced his sketch. There was a precedent for my quest. The model for one of Thomson’s most famous paintings, The Jack Pine, was supposedly identified in 1970 on Grand Lake, near Achray, on the eastern edge of Algonquin Park. Today a plaque proudly commemorates the spot as “one of the most famous sites in Canadian art history.” Alas for artistic pilgrims, by 1970 the tree was dead and—in what makes a sad, undignified end for a Canadian icon—burned by campers for firewood.

Thomson, handily, offered a clue to where he painted the oil sketch for Byng Inlet. On the back of the small wooden panel, he inscribed, in pencil: “Georgian Bay—June 1914, Behind Giroux light at entrance to Byng Inlet.” “Giroux light” is a reference to the lighthouse on Gereaux Island, now managed by the Canadian coast guard. Given that, according to a 1911 survey, Gereaux Island is only 2.42 acres in size—a little larger than a football field—finding the spot where Thomson had painted seemed as if it shouldn’t be too difficult. I even had, courtesy of Holmes, a 1921 aerial photograph that showed several likely looking stands of trees behind the lighthouse. Even more promising was the fact that Holmes put Peter Raymont and me in touch with Bill Franks, a doctor who owns a cottage in the area. Dr. Franks, an enthusiastic painter, used to canoe and sketch with A. Y. Jackson, and he once accidentally shot a Lismer painting with a BB gun while hunting bats at Dr. MacCallum’s cottage. A guide with more impeccable credentials could hardly be imagined.

There was, however, one potential difficulty. How interested was Thomson in topographical accuracy? He was painting a picture, after all, not taking a photograph. In 1919, Jackson suggested that he and his friends weren’t trying for verbatim transcriptions of the landscape when they went up north. “We felt that there was a rich field for landscape motives in the North Country,” he wrote, “if we frankly abandoned any attempt after literal painting, and treated our subjects with the freedom of the decorative designer.”

Just how topographical accuracy was sacrificed by Jackson and his friends I had recently seen at the McMichael. The exhibition Following in the Footsteps of the Group of Seven juxtaposed some of the group’s paintings with photographs of the Killarney landscape taken by Jim and Sue Waddington on the spots where, after much canoe-based sleuthing, they deduced the painters had worked. The paintings proved to be clever dances of inclusion and exclusion, the visual data of the landscape carefully and artfully sieved before reaching the canvas. Cézanne once claimed that he would rather smash his canvas than invent or imagine a detail in his painting. For a later generation, however, truth to nature was less important than emotional values and visual effects—and it was okay to invent or imagine. The huge rupture marked by this aversion to what Jackson called “literal painting” is made clear in a startling piece of advice from Paul Signac: “Sitting down in nature and copying what you see is not the way to make a painting.”

Thomson’s finished work in the McMichael is so intense and exciting precisely because it’s not meant to be a “literal painting”—a straightforward transcription of trees, rocks, and water. Instead, it’s a joyous celebration, a transformative work of art that splinters surface forms into bright shards of colour. There’s a vibrato sky, licks of red in the water, passages of blue in the trees and teal on the boulders, and what was fast becoming a Thomson trademark: branches tracing elegant arabesques. Thomson is, of course, back in his Toronto studio when he works on the canvas. Far from the waters of Georgian Bay, he flexes his artistic muscles, selectively screening and manipulating the raw data of the landscape, riffing with his paints and brushes to achieve pyrotechnic effects that can’t really be compared with the vista he glimpsed—or indeed the small panel he painted—on Gereaux Island.

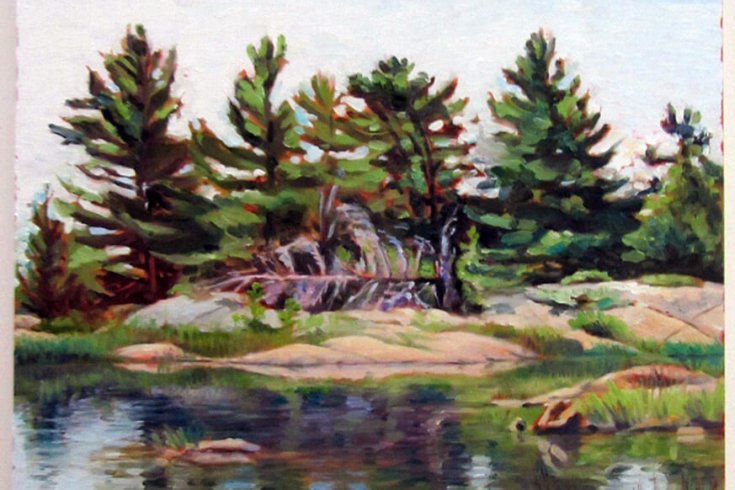

Dr. Franks, a tanned, vigorous septuagenarian who arrived on the island by rowboat, was confident he knew the spot where Thomson painted his sketch. So, armed with reproductions of both the sketch and the finished painting, our expedition made its way onto the island. Warning us about poison ivy, Franks conducted us to a benchlike stone—a sort of prehistoric pew—situated a short distance behind the lighthouse. His theory was that Thomson sat on this inviting perch and, looking across a small inlet to a stand of white pine, began his sketch. Sitting side by side on the bench, Franks and I held up the copy of Thomson’s sketch. All the elements certainly seemed to be in place: the foreground haunch of granite, the strip of water, and, of course, some pirouetting pines.

The view was eloquent. I could easily imagine how, sitting on this same slab of granite, Thomson first saw the possibilities of turning the ubiquitous white pines of the Canadian Shield—trees he would have seen on dozens of islands like this as he made his way along Georgian Bay—into his kinetic, expressive forms. Before Thomson, the eastern white pine was used for everything from ships’ masts and log cabins to hemorrhoid ointments, but few realized its artistic possibilities. Watson and other Canadian landscapists such as Carl Ahrens preferred mellow portraits of mossy oaks. After Thomson, Canadian landscape painting would produce an unending procession of threadbare pine trees dancing on ledges of rock (many came from the brushes of the Group of Seven, as if in tribute to Thomson). But all of those trees, it suddenly seemed to me, could trace their lineage back to the ones behind the lighthouse on Gereaux Island. Alas, like the Jack pine on Grand Lake, these trees were immortal only on canvas. Two of them were dead, one toppled sideways, its shallow roots a dirt-caked filigree, the other a greying column. It was difficult to resist making our way around the inlet to claim a relic of the True Cross.

But then doubt set in among the faithful pilgrims. Making our way back to the water taxis, a few people in our expedition, without wishing to gainsay Dr. Franks, started suggesting additional spots from which Thomson might have painted the trees, or even other groupings of trees he could have painted. Alternative, equally plausible locations were tried and tested. Thomson could have stood five metres to the left of the bench… or maybe six metres to the rear, where the perspective was equally if not more persuasive. As we stumped through the sumac and tall grass, trying out still more prospects, I thought of the early Arctic explorers, crawling through the snow on their bellies as they tried to find the north magnetic pole as it drifted elusively from beneath their dip circles. Thomson, so close but ever fugitive, seemed to recede from me once again.

Of course, it doesn’t matter whether or not we found the precise spot where he painted, or if the trees he painted are no more—because so many other trees, and so many other scenes that might have inspired him to take up his brush, are still there, on Gereaux Island and elsewhere. The spirit of those vivid snapshots on the walls of the McMichael—the windswept, frost-hardened genii loci of the northern woods—can be found everywhere in this part of Ontario. Turn a corner, take a bend in the river or a path through the woods, and a Thomson vista springs magically into view. Snow-stooped or frost-rimed fir trees; susurrating yellow aspens or crimson fringes of sumac; a November sky brooding over the dull menace of a northern lake. And almost always that image of survival and defiance: a pine tree shadow-boxing on a choppy shoreline. For those of us who love this landscape, the ancient question of St. Hilary of Poitiers—“Who can look on nature and not see God? ”—can be given a Canadian twist. Who can look on nature and not see Tom Thomson?

This appeared in the November 2010 issue.