The rain that June was so heavy not even Douglas Haig could ignore it. But the commander of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) was not the sort to give in. Bad weather had to be endured. The rain, though, was more than just unpleasant. It was torrential. Trenches were waist deep in water. With the French facing huge losses at Verdun, Haig had been charged with launching a major offensive on the German forces entrenched along the forty-kilometre front that straddled the banks of the river Somme. But the downpour postponed the “big push.” So Haig set an alternate date: July 1, 1916.

A regiment from Newfoundland played a role. Not a key role, to be clear. There were no key roles. Haig’s strategy, such as it was, ensured that companies in the first and second waves of the advance would face equal danger. When their time came, the Newfoundlanders were expected, like every other unit, to walk toward the weapon responsible for the long stalemate of the Great War: the machine gun.

Haig believed absolutely in what he was doing and was untroubled by its human cost. He was not cruel. He was not insensitive to grief. But when it came to the casualties he was willing to tolerate, he did not think small. Like most of the politicians and military leaders of the day, Haig looked as if he belonged in the nineteenth century. He cut a fine figure on a horse. But by 1914, lances and chargers were things of the past. Haig’s thinking, however, didn’t venture much beyond the confines of his education. He was the kind of man who applied old strategies to new conditions. He trusted in the big assault—the clash of armies, strength against strength.

He wasn’t alone. Tactics that had been the foundation of battle since Napoleon’s Waterloo were more or less transferred to the first years of the conflict. The results were horrifying—and never more so than that summer, in the lines of trenches dug southwest of the small French village of Beaumont-Hamel. The first day of the Somme offensive would prove the most catastrophic twenty-four-hour period the British Army had ever endured. Almost 60,000 of the BEF died. No unit was spared. But the Newfoundland Regiment can stand as an example of what happened that morning when Haig opened his attack.

At 8:45 a.m., the signal came for the Newfoundlanders to go over the top. Approximately 800 advanced. At roll call the next morning, sixty-eight answered.

The notion that a war can ever actually end is a comforting fiction. But if the crowds that gather silently in downtown St. John’s every July 1 prove anything, it’s that wars have a way of living on long after the guns are silent—in the bereavement of families, in the nightmares of veterans. Few conflicts have faded from memory more slowly than the First World War, and probably nowhere was its damage more strongly felt than on what was seen at the time as an obscure island in the North Atlantic.

That the tiny population of just under 250,000 raised a regiment at all in 1914 was improbable. A regiment—typically a unit fiercely proud of its local roots—consists of about 900 men in the field and 100 in reserve. It would have made more sense for volunteers to join up with the British Army. But England’s oldest colony, in what can only be described as a burst of patriotism, set itself the challenge of shipping its own soldiers overseas.

Sir Walter E. Davidson, the governor of Newfoundland, cabled the secretary of state for the colonies and suggested that his territory could muster a force of 500 within the month. His Majesty’s Government gratefully accepted the offer, and from that point on, things moved quickly. The costs of feeding, clothing, supplying, and training Newfoundlanders —and then transporting them to European battlefields—were considerable. The island barely had a police force. Except for the few naval reservists who were not out on the fishing banks, there was virtually no military infrastructure—certainly nothing on which to build anything so ambitious as a regiment. The Newfoundland Patriotic Association was created to make it happen. The association began the war by borrowing $250,000—the first of many loans.

How would Newfoundland pay for it all? No one had a clue. The question was the last thing on anyone’s mind when, on October 3, 1914, the St. John’s crowd cheered as the SS Florizel headed out to sea. On board was the first contingent of men, my grandfather among them. They were called the Blue Puttees, on account of the most eye-catching element of their hastily improvised uniform.

Nobody expected the war to last more than six months. It lasted four years and was fought at a cost—in lives, in material, and in money—that by today’s standards is almost unimaginable. More than 6,500 young Newfoundlanders enlisted, and because of casualties sustained at later battles—at Gueudecourt, at Monchy-le-Preux, at Cambrai—1,305 of them abruptly vanished from a population the size of Regina. In the decades that followed, several thousand more wounded, disabled, and “shell-shocked” veterans required the kind of care and treatment that Newfoundland was too impoverished to provide.

Other countries were left with enormous bills after hostilities ended, not least of all England. But Newfoundland’s were more staggering than most. The year it began sending soldiers into battle, it was saddled with a national debt of nearly $30.5 million. By 1919, it was $42 million. Then came the world collapse of iron, timber, and oil prices (all exports on which the colony relied). Then came the Depression.

By 1934, when Newfoundland voluntarily abdicated its government to a committee of Colonial Office appointees, the island was on the brink of bankruptcy. Yet Britain’s acknowledgment of Newfoundland’s sacrifice was never much more than ceremonial (the Newfoundland Regiment became the Royal Newfoundland—an honour bestowed by King George V after the 1917 battle at Passchendaele). England had its own war debts and by the end of the Second World War was in no position to assist destitute colonies—no matter how bravely their sons had fought in the Great War.

In 1949, the island that my Newfoundland grandfather considered his country bowed to the inevitable. It became a province in a much larger country—a country that celebrates its own confederation on July 1.

Haig emerged from the war a hero, which shows how confounding history can be. There was no doubt he was a stalwart soldier. And an ambitious one. But sharp as his political instincts were, skilled as his networking was, there’s good reason to believe that he was, as the historian Jack Granatstein once described him, “bone stupid.” Certainly, the strategy he employed at the Somme provided no evidence to the contrary. From the point of view of the BEF, the battle was a case study in how not to fight a modern war.

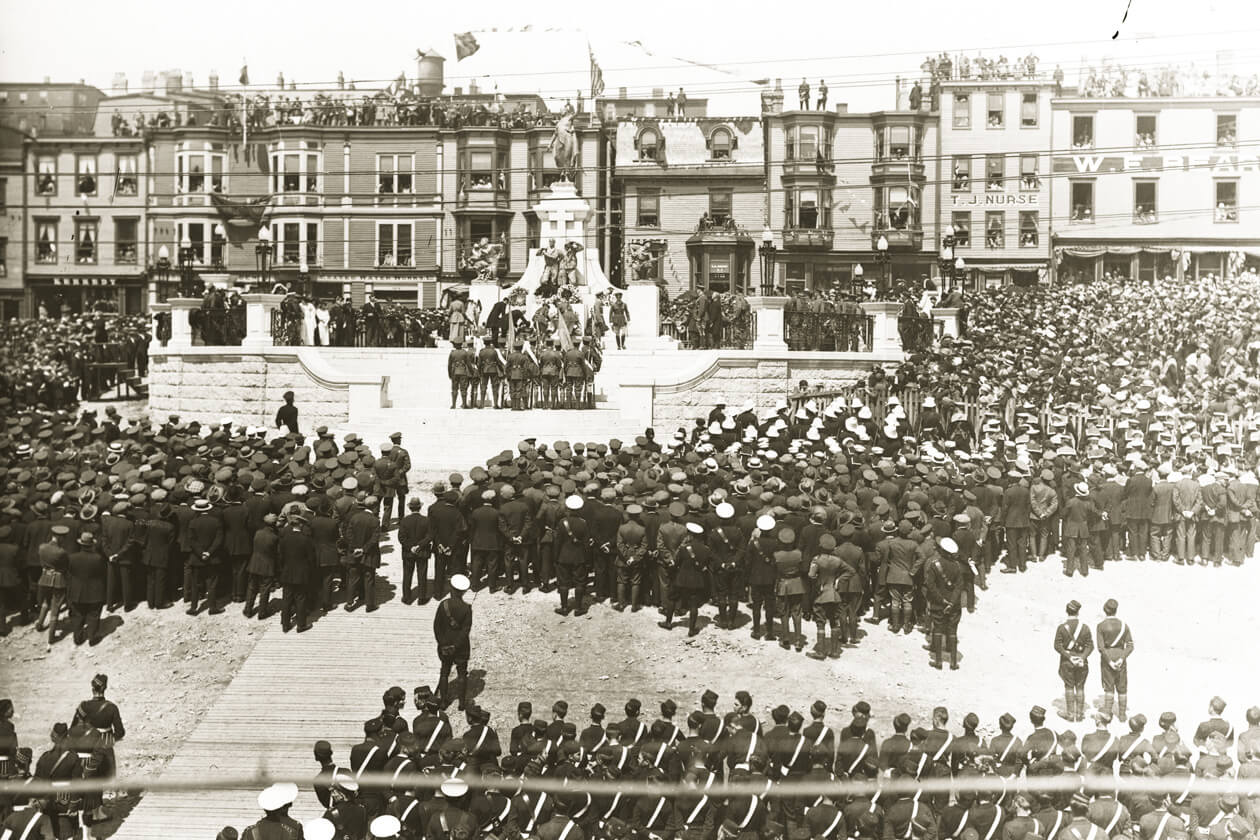

And yet, there was “Butcher Haig” in St. John’s on July 1, 1924, the honoured guest of the Dominion, invited to unveil the city’s war memorial. How come nobody booed? Newfoundland suffered the largest loss per capita of any colonial participant. In my grandfather’s family, five of six Goodyear sons enlisted: three were killed, and two were seriously wounded. But this wasn’t unusual. The Goodyears were no more ill-fated than many other families. From St. John’s wealthiest to the outport’s poorest, the fatalities were everywhere. Who knows how many families unravelled after the deaths of sons, husbands, brothers, fathers, cousins. Michael Winter’s book about the First World War’s legacy in Newfoundland, Into the Blizzard,had its genesis when he moved into a house in Western Bay ten years ago. He wanted to buy the adjacent field and learned that it had been owned by a family whose nineteen-year-old son, Richard Sellars, had been killed in 1916. “If Richard Sellars had lived and had a family, he would have had a stake in this land,” writes Winter. “Today, my family lives our summers on a land meant for a man who fought in the First World War.”

When Haig stood to speak ninety-two years ago, he was addressing an audience made up of those whose lives and ambitions had been shattered, largely as a result of his orders. He described the sympathy he felt for Newfoundland’s loss and went on to praise the “high courage and unfailing resolution all ranks set themselves to accomplish all that was asked of them.”

Why was the architect of a great military disaster invited to appear at this event, and then, in the following year, to be the guest of honour at the unveiling of the Newfoundland memorial at the site of the Somme battlefield? Because the cost of the war was so severe it took generations to see things objectively. It was difficult for those who had lost so much to admit what many in the province now accept as the truth: it was all a terrible waste.

Haig was right about one thing: the Newfoundlanders were brave. He and his commanders were so confident about the five-day artillery barrage that had preceded the Somme advance that troops were ordered to proceed as if enemy positions were taken up by corpses. The Germans—too dug in and too well supplied to have been greatly unsettled by the shellfire—could hardly believe their luck. An army was marching at a slow, steady pace toward them. There was no need to aim; fixing their guns on the gaps in the barbed wire was pretty much all the skill required. The dead lay in heaps.

From a strategic point of view, Beaumont-Hamel changed nothing. The war slogged on. Mud was won; mud was lost. But from the point of view of Newfoundland, it changed everything. The island’s economy, its politics, and the very fabric of its society were never the same. “We are an island,” says Kevin Major, whose 1995 novel, No Man’s Land, centred on the Newfoundland Regiment’s last hours before the carnage. “And there was no place that wasn’t ripped apart by that battle. There was no place it wasn’t marked into our consciousness.”

In a uniquely Newfoundlandish way, this island was accustomed to disastrous news. Fishermen were always lost. Ships were always wrecked. Men died because they needed money—and they needed to imperil themselves in order to get it. In the spring of 1914, five months before war was declared, the bodies of scores of sealers who had perished in a blizzard on the ice floes were unloaded like stacked wood from the decks of the ships that had found them.

In the years ahead, the Battle of Beaumont-Hamel, terrible as it was, would not seem like an aberration of history. As Newfoundland’s debt compounded, as its businesses foundered, as it politicians squabbled, Newfoundlanders—particularly the young—were forced to leave their homes to find work. They went to sea, of course, and to the ice floes, and later, as the wheels of Newfoundland’s economy ground down, to the steel mills of Hamilton, the auto plants of Oshawa and Oakville, the nickel mines of Sudbury, the oil fields of Alberta, and the tar sands of Fort McMurray.

Those disappearances weren’t caused by a single debacle, as was the case at the Somme. But they are gaping absences all the same—of youth, of talent, of skill, of capital, of ideas, of ambitions, of dreams. And perhaps that is why Beaumont-Hamel is so central to the province’s sense of itself: in a place so small and so tightly knit, every loss chips away at its future. Haig’s cruel strategy wasn’t unfamiliar to Newfoundlanders. In a cold, remorseless way, it was Newfoundland writ large.

From the trenches, the Newfoundland Regiment could see the stump of an old tree. It marked the eastern periphery of the churned wasteland over which they would cross on the opening day of the Somme. They called it the Danger Tree. There is something strangely blunt about that nickname—especially considering the island’s collective genius for colourful proper nouns (Blow-Me-Down, Heart’s Content, Seldom-Come-By). For once, Newfoundlanders were understated.

And they continued to be understated. Thirty years ago, I remember asking one of the few surviving veterans of the Great War about his experience. He said, “It’s hard to credit.” And then he stopped. There was nothing more to say. We can’t ever know what it was to be an eighteen-year-old boy waiting at the wall of a trench or what it was like to clamber into an open field, 600 metres away from the German guns, and walk forward—chin instinctively tucked into one’s advancing shoulder (as one observer noted) as if fighting against a blizzard in some little outport. And most unknowable of all: that convulsion of gut and soul that would be the last thing he felt.

Today, the battle is remembered in great detail at the Beaumont-Hamel Memorial in France: the battlefield is largely preserved, and the whole park is surrounded by 5,000 trees native to Newfoundland. Then there are the exhibits at the Rooms in St. John’s, a museum that also maintains a website containing, among other things, the military files of over 2,200 regiment soldiers. And there’s hardly a legion hall on the island that doesn’t have photographs and mementoes on its walls. Accounts of the war have also been published, from the letters of Private Frank “Mayo” Lind (so nicknamed because he wrote home about the tobacco shortage at the front, which led to packages of Mayo tobacco being sent overseas) to Newfoundland’s first novelist, Margaret Duley, who wrote about the war’s effect on outport communities in her 1939 novel, Cold Pastoral (Duley’s older brother was severely injured at the Somme). The final scene of Michael Crummey’s 2009 novel, Galore, features a soldier returning home from the battlefield. In Richard Greene’s 2014 poem “Corner Boys,” the author remembers, as a boy, having seen

the last of the Blue Puttees, the men

of Beaumont Hamel, of Arras and Cambrai;

crutch-propped corner boys on Water Street,

backs to brick and stone, their salient

a length of pavement and a few small shops.

Most recently, Corner Brook’s Jackie Alcock sowed thousands of fabric forget-me-nots onto an old military blanket to honour Royal Newfoundland Regiment soldiers.

And yet, it’s still hard to credit. Because history is so difficult to feel, we codify it with dates and numbers. But those dates and numbers are useful only if they help tell us something about what a place is like. Circumstances in Newfoundland were bleak in 1914, so bleak that the dollar or so a day that a private made was reason enough to enlist. And that hasn’t changed. Today, as in 1914, enlisting for a Newfoundlander means training you wouldn’t otherwise get and money you wouldn’t otherwise earn. It also means adventure—however sad the adventure’s outcome may be.

I was in Newfoundland last November as part of a Remembrance Day assembly at Roncalli Central High School in Avondale. High-school students do not always make for the most attentive audiences. But this group was rapt. They knew why the university in St. John’s is called Memorial. They understood what the mural of a dead tree on the wall behind us represented.

Wars aren’t ancient history in Avondale. A Canadian soldier named Jamie Murphy was killed by a suicide bomber in Afghanistan in 2004. He’d gone to Roncalli. People knew him well. His mother and father lived nearby. There are teachers at the school who had him in their classes. If remembering that young man leads to the battlefields of the First World War—Beaumont-Hamel being the most tragic of all—that’s because July 1 is not simply a ceremonial remembrance. It’s a visceral inheritance, the collective recollection of the day Newfoundland lost more than what it was. It lost what might have been.

This appeared in the July/August 2016 issue.