Montreal artist Valérie Blass makes bewitching sculptures out of found objects—housewares, wigs, shattered ceramics—which she gloms together under plaster, plastic, paint, and polish to create disarming figurative and abstract works. This combining and modifying is a time-worn technique adopted from art history’s most famous borrower, or bricoleur, Marcel Duchamp. A bricoleur, by his definition, is someone who knows a can of acrylic paint is a found object; for her part, Blass selects her materials from hardware stores, Dollaramas, and city sidewalks.

Like the French American artist Louise Bourgeois, Blass sees neurotic tendencies in common objects, as with her Midnight Viper, a ceramic bust with a teapot ear and a fortune kitty for a proboscis. Her works derive their engagement from their dark humour and the mythic, uncanny familiarity of their forms. Even her least figurative pieces insinuate something grotesque when placed next to L’homme souci, an armless black body made of hair extensions and Styrofoam, standing in Miu Miu shoes. étant donnés, named after Duchamp’s last sculpture, is a yeti-like lion with a frightened white marsupial clinging to its chest like a visual pun. Blass has also made irreverent odes to the modernist sculptor Constantin Brancusi, with her own ceramic pipelines to heaven. She exhibits an affinity for the most perverse contents of any culture’s folk tales. “I’m not so much interested in Chinese art,” she has said. “I’m more interested in chinoiserie—an interpretation of an interpretation of an interpretation.”

The Walrus commissioned the pieces pictured here for an ongoing folio of new works by Canadian artists. This offers the opportunity to reverse the typical arrangement where an artist contributes spot illustrations to be framed by journalism.

The facing page shows four sculptures about the size of Duchampian chess pieces, each combining two or three ready-made objects to form particularly masculine or feminine figures. René Magritte’s painting of a tobacco pipe, Ceci n’est pas une pipe, referred to the illusion of representation, as well as the popular Freudian theory that associates the pipe with the male organ. Blass’s little male beasts are reduced to this metonym, with their central orifices atop a pipe stem. The female figure in the bottom right corner, a thimble-faced siren stroking her copper limbs, is a bald-headed version of Blass’s life-sized 2009 sculpture She Was a Big Success, with a mannequin’s thin arms and legs propping up the headless tower of a voluminous black wig.

At the bottom left sits a more androgynous type, whose Styrofoam nose and long-brimmed hat droop over a hunched body, hidden beneath the shimmering, glazed robe of an old tchotchke. There’s much emaciated wisdom in this hammerhead.

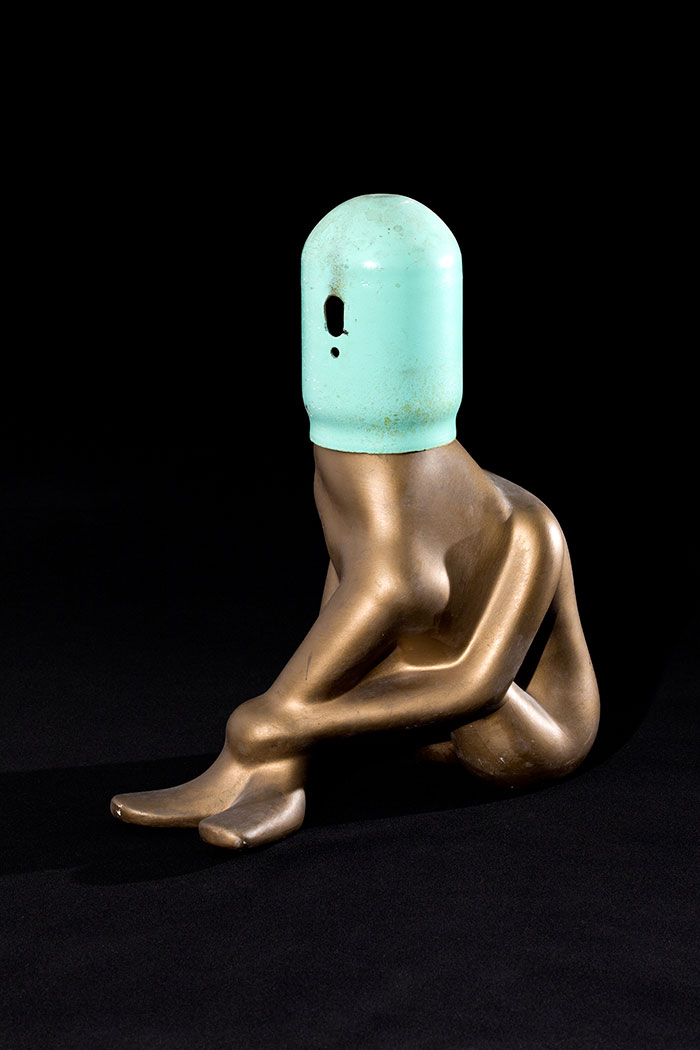

The following pages show two almost identical versions of a toxic Pietà, an irradiated madonna melting over the son buried against her jaundiced breast. She is something of a goddess and much like a witch. The child is both alive and dead, restrained by the same embrace that holds him upright. The mother is reminiscent of Baba Yaga, the witch from Russian folklore, who lives in a hut propped up on four giant chicken legs and pilots a huge stone mortar and pestle through the woods, devouring nasty children. Blass’s figure is a blessed demon to her suffocating child; they eat each other as life eats them. Their tragic relationship is the transaction of myth. Their conflict is the bond.

In the way that Bourgeois employed vanity mirrors, spiders, and cages, Blass uses her own combinations of kitsch to create a Value Village vision of classic monsters: golem, Windigo, siren, sasquatch, Galatea, Medusa, Grendel. She trawls through the dark lakes of the psyche for strange, half-known figures with bodies as defaced as those of a Hans Bellmer sculpture, as disfigured as a Giacometti, improvised like a Dieter Roth.

Other Canadian artists—David Altmejd, Shary Boyle, Liz Magor, and the Royal Art Lodge—have contributed analogous depictions from this parallel universe of uncanny resemblances, a collective dream in which daylight objects fly together to narrate a coherent disorder. We are never far from the monster in contemporary art, because the new is often unsettling. In the sculptures of Valérie Blass, we are startled to see the profound fear and misery that lie at the heart of everything we hold to be true and beautiful.

This appeared in the November 2011 issue.