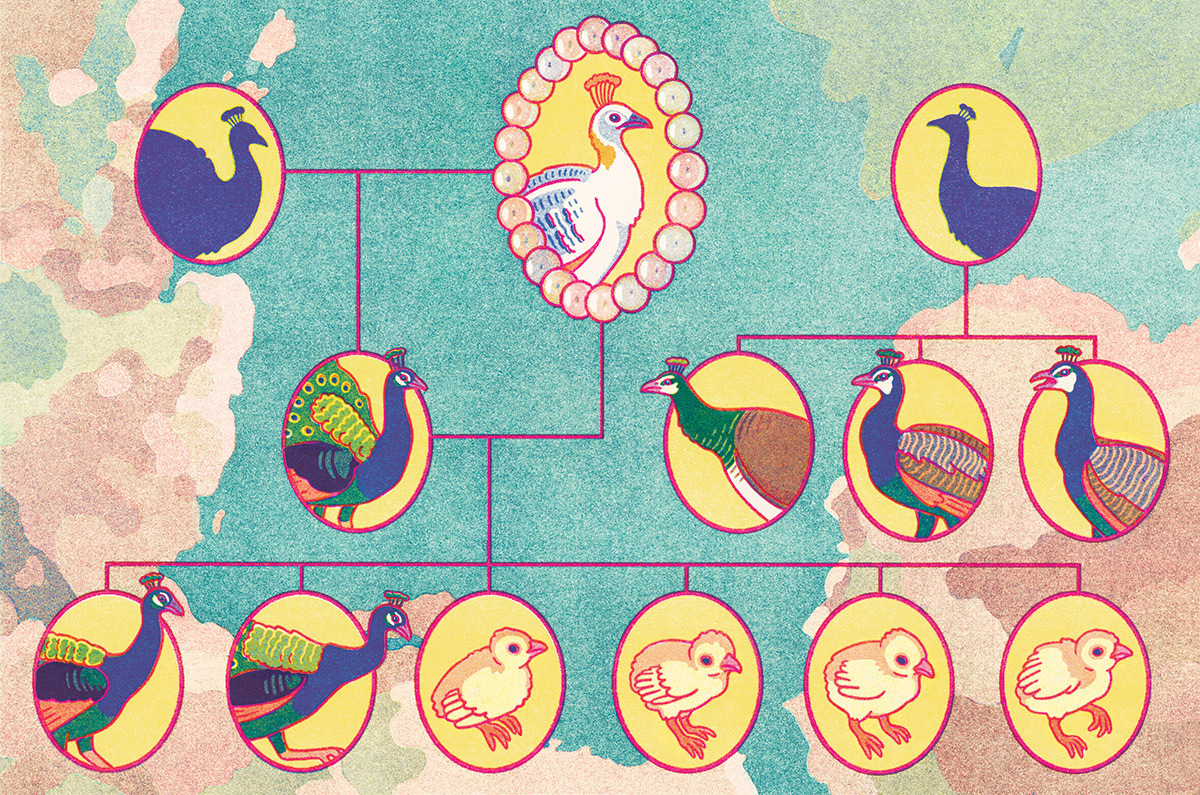

It began with a peahen named Pearl. She was the only female in a trio of peafowl that once freely roamed the small town of Naramata, British Columbia. Her chicks had the bright-blue bodies and metallic-green tail feathers that make the male members of her species iconic, but Pearl’s colouring was rare: her entire body and tail feathers were a shimmering white.

Peafowl in Naramata have been traced back to at least 2010, though some say Pearl arrived in the early 2000s, rumoured to have escaped from a nearby ranch. Over the years, Pearl mated with one of her chicks, and the flock eventually expanded as she continued to breed. Still, when and how the birds first arrived in town is a mystery. In a book of Naramata history, community historian Craig Henderson concedes that, really, “no one knows.”

Perhaps, though, no one wants the blame. The peafowl eventually became a source of tension in this quaint community on Okanagan Lake, in southern BC’s wine country. As their numbers grew, they made more and more of the town’s infrastructure and environment their own. Tourists loved them, and for some residents, they were a welcome addition to the town’s ambiance. Some people provided bird food throughout the winter or built shelters in their yards and filled them with hay or blankets, “kind of like the manger,” recalls local singer Yanti Sharples.

The peafowl seemed to follow a sort of daily migration, commuting from yard to yard, says local librarian Joanne Smiley. But the birds also ate from those yards, helping themselves to vegetable patches and petunia plants. The peafowl were, after all, wild, and they roamed and made roosts wherever they pleased. They peered into windows, staring at their own reflections. They climbed on top of cars so often, leaving deep scratches from their long talons, that people started putting large stuffed animals on the hoods of their cars, says Sharples, like fluffy scarecrows. One peafowl was known to sleep in the branches of a ponderosa pine outside the public library and peck at the flowerpots out front. What small towns become known for is sometimes a product of chance and often not universally welcomed. For Naramata, its peafowl became a fulcrum of what the town is and what it wants to be.

Every Thursday, the peafowl could be seen chasing the garbage truck. Their droppings littered the streets, and their shrill cries echoed throughout the quiet town. To Smiley, it sometimes sounded like a silly cackle. “You might think, They look beautiful, so they might sound beautiful. They do not.”

Other than from an aesthetic perspective, peafowl are essentially useless. Though, if English poet John Ruskin is to be believed, the “most beautiful things in the world are the most useless; peacocks and lilies, for instance.” Mostly, they just walk around and put on a show. For such a big bird, they have a negligible impact on the balance of an urban ecosystem—apart from a nibble here or a peck there. Likewise, not much pushes back: in North American cities, predators of peafowl are most likely to be dogs or raccoons. Beauty is the peafowl’s saving grace. Their feathers are long, colourful beacons splayed confidently, and the plumage is a protector of the species: peahens are attracted to peacocks with long tail feathers and piercing ocelli, the round, eye-shaped tips of the feather. It so happens that the same aesthetic trait attracts gawking humans too.

Even when his tail is not on display, a peacock’s feathers are clumped in a long train that flows behind him as he walks, a veil-like accessory. “If they weren’t beautiful, no one would love them,” says Smiley. “And they are exceptionally beautiful.” That they became emblematic of Naramata speaks in many ways to the people who live there rather than to the animals themselves.

Situated on some of the most coveted land in the Okanagan region, Naramata has historically enticed creative, one might say eccentric, residents. While the rest of the Okanagan wine region has cultivated a polished, Instagram-filtered glow, Naramata has held fast to the bygone off-the-grid pace that drew small homesteaders and orchard operators to the region in the 1960s and ’70s. The peafowl came to fit the image of the town, which has been described as “bench bohemian” (a reference to the Naramata Bench, a subzone of the Okanagan Valley), “artistically unconventional,” and, once, “a will-work-for-crystals economy.” As tourism boomed in the region and orchards were tilled into vineyards, Naramata’s peafowl became an attraction in their own right.

Witnessing such eye-catching fowl idling around urban areas is not unique to Naramata, but peafowl differ from other birds that are symbolic but also native, like the eagles that soar above Vancouver, the seagulls that flit around Halifax, or even the Canada geese that strut on golf courses across the country. All these birds bring annoyance to human communities in much the same way peafowl do—noise, droppings, property damage, territorial aggression—but those inconveniences might be easier to brush off because they’re local. They’re ours, part of the natural world we have built our lives in.

Peafowl, though, native to the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia, are an introduced species in North America. They were brought to populate hobby farms or the estates of (often wealthy) landowners who wanted to see a peacock silently glide and unfurl its feathers in an elegant display. But the birds have often been left behind when those owners moved, or they have escaped from properties that aren’t secure. In places like Naramata, they have then become feral.

Peafowl are not covered by BC’s Wildlife Act or any other provincial or territorial wildlife act, which makes it difficult to responsibly remove them from a municipality where they roam free. They’re also not considered game birds. And to tamper with their eggs is an offence punishable by a $300 fine. In 2019, dozens of feral peafowl dominated the Sullivan Heights neighbourhood of Surrey, BC, leading to complaints by residents at their wits’ end. It was a small farm that had brought the peacocks to Surrey in the first place: when the farmland was developed, the birds stuck to their territory.

The municipality struck up a pilot project, trapping and putting the birds up for adoption through the Surrey Animal Resource Centre and relocating them to wildlife sanctuaries, zoos, and farms. The eventual trapping program was rolled out slowly, though, and over a year later, a dozen still remained in Sullivan Heights. Some residents told the media that they wanted the peafowl to stay; one resident, reportedly frustrated by the city’s inaction, felled a large tree in his yard that had become a popular roosting spot. The peafowl in both Naramata and Surrey came to exist in a grey zone—neither wildlife nor pets, beloved and despised, and impossible to legislate.

In September 2010, a community meeting about Naramata’s peafowl population was held at the OAP (Old-Age Pensioners) Hall. The meeting, which filled the hall to capacity, was sparked by an anonymous homeowner who, worried about expanding brood size, had hired a trapper from nearby Peachland to capture Pearl and her chicks and move them to a petting zoo. The trapper, Larry Fehr, had built a large wooden trap on the homeowner’s property. “This was the first time I ever caught a peacock,” he says in Henderson’s book on Naramata’s history.

Fehr captured the birds on private property, but their status—somewhere between wild and domesticated—meant that they didn’t technically belong to anyone. This, naturally, ruffled feathers. The line had long been blurred between wild animals surviving in an urban environment and beloved pets who belonged to the town. In the days that followed, it emerged that three of Pearl’s chicks had died after being transported to the zoo. A delegation of townspeople visited the zoo to check on its conditions.

By the September meeting, tensions were high. The town was divided over what to do about Pearl, now some sixty kilometres away; over how her relocation had taken place; and over the fact that a trapper had been called without a town meeting. “I love Pearl dearly,” said resident Carol Shea, according to local news site MyNaramata. “I’ve admired her fabulous mothering instincts with her chicks. I really love our Naramata peafowl. . . . But I don’t want twenty or thirty of them.”

Another attendee suggested forming a bird society to bring Pearl home and provide public education around peafowl care. No one agreed to join, and as Henderson writes in his book, the proposal was shut down by a regional district employee who cautioned that anyone who brought back Pearl and her chicks would need to enclose them to prevent them from roaming the town unchecked. Essentially, someone would need to take ownership of the birds, turning them into pets. Resident Carol Allen later commented on MyNaramata that this sentiment “hung over the meeting like the ghost at a banquet, intimidating attendees into a state of paralysis.”

The meeting, it was agreed, was essentially useless. Pearl (who had been renamed Naramata at her new home) remained a resident of the petting zoo. According to MyNaramata, though, “most attendees learned something about peafowl, and just about everyone felt that the chance to talk about an issue with neighbours is always an exercise in community building.”

“After the meeting,” an attendee later commented on the local news site, “I wondered how long Naramata will remain distinctive . . . . ”

When one peacock was killed by a dog, someone said that it was as if one of her children had been killed.

The trapper left behind three peacocks to roam free in Naramata. When one was killed by a dog, someone commented on MyNaramata that it was as if one of her children had been killed. The two remaining birds were dubbed Peter and Kevin. They lived in the ponderosa pines near the public library and moved freely around town for more than a decade.

Three more peafowl reportedly appeared on Naramata’s streets in 2014, four years after Pearl and her chicks had been relocated to the petting zoo. How they arrived in town was a mystery. “I am wondering where they came from, if it is immaculate conception, because to the best of my knowledge there is no female,” said Janet McDonald, executive director of The Centre at Naramata, according to local news site Castanet. But the three reportedly didn’t remain long.

A sort of détente was reached regarding Peter and Kevin. Knowing that they couldn’t mate and expand the pack was a consolation. Some Naramata residents felt that the peacocks had essentially become an integrated part of nature in their small town. It appeared that, after so many years, Naramata had finally come to accept its resident peafowl.

In January, however, Kevin disappeared. Residents discovered iridescent blue-and-green plumage scattered in the snow at two sites: in a backyard near the library and behind the Naramata Inn. The inn posted a short eulogy on Facebook: “Kevin’s swagger, regal beauty, confidence, and quirkiness will be dearly missed. Rest in power Kevin.” Shortly thereafter, Peter vanished as well. It’s suspected that they died by bobcat, but neither bird’s carcass was ever found. Yanti Sharples wrote a memorial song for the last of the Naramata peacocks. As mysteriously as it began, the town’s turbulent history with peafowl came to an end.

Naramata has recently been experiencing a culture shift—a booming housing market, glossy new vineyards, well-heeled tourism. With Kevin and Peter presumed dead, the town has lost a symbol of itself, a surprising reminder of its quirky and colourful roots.