For his fans, there was so much to love about Leonard Cohen. His rare ability to be sardonic and generous at the same moment. His self-deprecating humour—the gravelly, knowing way in “Tower of Song” that he would intone, “I was born with the gift of a golden voice.” The man embodied cool, without ever quite discarding warmth.

But most of all, we loved his fearlessness. Cohen, who passed away on November 7, at the age of eighty-two, was constantly ready to reimagine himself. Uneasy in his guise as a soulful poet, he became an innovative novelist. Constrained by the printed page, he turned into a professional singer. Discontented with his image as a world-weary lady-killer, he took up the study of Zen. Unwilling to accept the role of a placid sage, he spent much of his seventies performing in venues as untraditional as Piazza San Marco in Venice and the Kremlin in Moscow.

I grew up in Saskatoon listening to his early albums in a small, unstylish bungalow on a windswept street. With its corrosive delicacy, its mixture of irony and passion, Cohen’s music seemed to arrive from some foreign country of the soul. It embodied a kind of sophistication I barely knew I craved. Years later, having chosen to make my home in Montreal, I realized these songs had been a subconscious influence.

During his later years, when he wasn’t on the road, Cohen spent much of his time in Los Angeles. But in at least a portion of his heart, he remained a Montrealer. His early songs are imbued with his home city—in “Suzanne,” “the sun pours down like honey / on Our Lady of the Harbour,” and in “The Stranger Song” the speaker proposes a meeting “beneath the bridge / that they are building on some endless river.” (It was the supposedly sturdy Champlain Bridge across the St. Lawrence, and Cohen, who wrote that song in the early 1960s, almost outlived it.) In his semi-autobiographical novel The Favourite Game (1963), the invalid father of the boy hero shows his son how to pat the noses of horses by the chalet on Mount Royal, and how to feed them cubes of sugar from his palm. “One day we’ll go riding,” the father says. “But you can hardly breathe,” the boy answers. That night the father collapses. Soon he is dead.

Cohen’s own father—a prosperous clothing merchant who owned a splendid house in Westmount, far from the scruffy neighbourhood of Mordecai Richler and most other Montreal Jews—died in 1943, when his son was only nine. The boy went on to McGill University and found a mentor if not a surrogate father in the poet Irving Layton, a generation older, who fondly referred to him as “golden boy.” “I taught him how to dress,” Cohen once said. “He taught me how to live forever.” Like so many of his gnomic statements, this was both tongue-in-cheek and flat-out serious.

“Some say that no one ever leaves Montreal,” he wrote in The Favourite Game, “for that city, like Canada itself, is designed to preserve the past, a past that happened somewhere else.” But of course Cohen did leave—for London, for the Greek island of Hydra, for New York, for LA, and for the Mount Baldy Zen Centre on the highest peak of the San Gabriel Mountains in southern California. There, for a time, he lived as a virtual recluse. The abbot of the Zen centre, Joshu Sasaki, or “Roshi,” filled somewhat the same role for Cohen in middle age that Layton had filled in his youth.

For all the seriousness of his Buddhist training, Cohen never abandoned his Jewish roots (his maternal grandfather was a rabbi, his paternal grandfather a founding president of the Canadian Jewish Congress). At a symposium held at the Jewish Public Library in Montreal in 1964, Cohen defined Judaism as “a secretion with which an eastern tribe surrounded a divine irritation—a direct confrontation with the Absolute. Today we covet the pearl, but we are unwilling to support the irritation.” From “Story of Isaac” to “Hallelujah,” many of his songs are drenched in the language and images of the Hebrew Bible.

“Our appetite for reverence has not been addressed very much,” Cohen said when I interviewed him for the Montreal Gazette in December 1993. He still had a house near Boulevard Saint Laurent; we sat in the small kitchen, where he brewed cup after cup of the most alarmingly strong coffee I have ever drunk. “Our appetite to respect,” he continued. “Our appetite to submit. Our appetite to obey.” But isn’t respect a far cry from submission? I asked. Cohen didn’t miss a beat: “One follows the other as the day the night. You only obey that which you respect.” He paused then, thinking about what he had just said. “But the only basis of practice that has worked for me is love.”

He was an unabashed lover of women. “She stands before you naked / You can see it, you can taste it, / And she comes to you light as the breeze . . .” A lot of male singers are never this direct, and certainly they never haul worship and blessing and heaven into a song about sex. Cohen made this seem only natural.

He had a kind of courtly gentleness about him, and a deep faith in his work that did not preclude genuine humility. “Much in me strives for this honour,” he said when he turned down the Governor General’s Award for poetry in 1969, “but the poems themselves forbid it absolutely.” Over coffee that morning in the kitchen of his stone-faced Montreal house, he admitted that “I can’t talk when there’s music in the background. When I listen to a singer—unless it’s Pavarotti, seizing me by the heart and throwing me over the edge of the world—I’m listening to another guy doing what I do for a living: revealing his position in the world.”

So many songs revealed those positions. “Hallelujah” may be his most famous song today—it is certainly his most recorded. But it arrived at a low ebb in his career. After the success of his first few albums, Cohen’s popularity began to wane in the 1970s. By 1984 he had been musically silent for several years, and his album Various Positions—which featured not just “Hallelujah” but “Dance Me to the End of Love”—was rejected by Columbia Records. There were periods of time when his following in Britain and Europe was larger and more faithful than his following in North America. But beginning in the mid-‘80s and stretching well into the twenty-first century, his sales and reputation kept on rising even as his cigarette-bruised, whisky-darkened voice kept on dropping to ever deeper levels.

If there were critics who doubted the quality of his music, as opposed to his poetry, those critics did not include Bob Dylan. “His gift or genius is in his connection to the music of the spheres,” Dylan told David Remnick, the editor of The New Yorker, in October. Dylan compared Cohen to Irving Berlin, saying that both songwriters “are incredibly crafty. Leonard particularly uses chord progressions that seem classical in shape. He is a much more savvy musician than you’d think.”

Throughout his long career, movie directors were happy to use Cohen’s work. His songs were featured in films as different as Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers and Atom Egoyan’s Exotica. Three songs from his first album provided an evocative soundtrack, improbably enough, for an anti-Western set in the Pacific Northwest, Robert Altman’s McCabe and Mrs. Miller. Even more improbably, Rufus Wainwright’s version of “Hallelujah” formed part of the soundtrack of Shrek. “Hallelujah” also showed up in the superhero movie Watchmen.

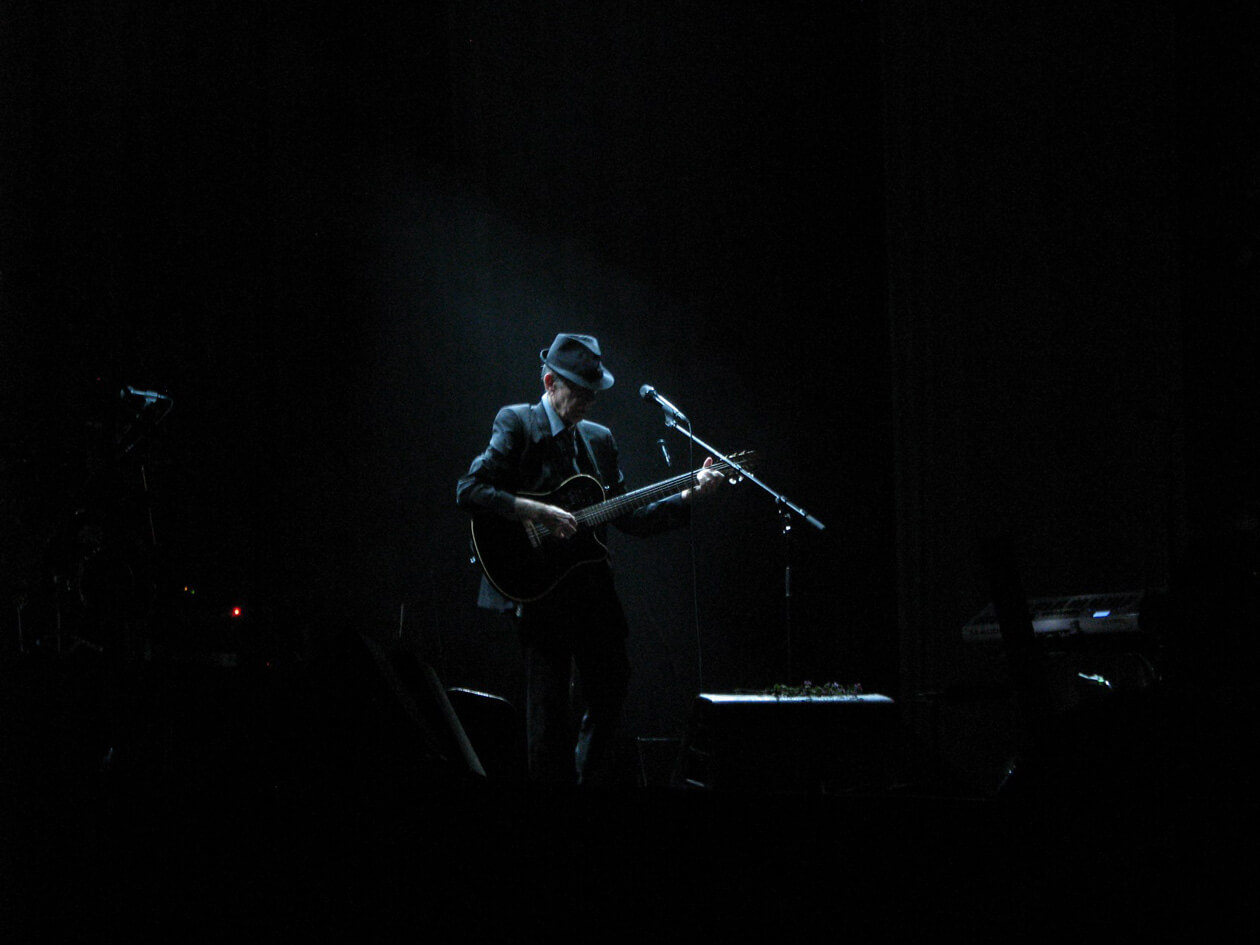

What the directors valued, I suppose, was also what we ordinary fans of his music valued: a willingness to plunge straight to the heart of emotion, conveyed not with the greatest range or the most powerful voice but with grace and absolute authenticity. I heard him live in Oxford in 1976; after the fourth encore, the house lights came on but the crowd refused to leave. Cohen reappeared after a few minutes, sat down on a stool and sang a fifth encore. I heard him again at the Bell Centre in Montreal in 2012, when he was seventy-eight years old. In the palace of hockey—the city’s true cathedral—he made twenty thousand listeners feel as if he was singing to each of them alone. Again the crowd demanded encore after encore. Again he obliged.

Cohen’s health declined after the final tour ended, yet he continued to write. The songs in his 2016 album You Want It Darker showed no decline in his lyrical talent, even though sexuality has receded and left the field, so to speak, open to God. The nubile women who accompanied so many of his albums were replaced by the cantor and choir of Congregation Shaar Hashomayim in Westmount, the synagogue of his childhood. “I better hold my tongue,” Cohen intoned in “It Seemed the Better Way, “I better take my place / Lift this glass of blood / Try to say the grace.”

Call it a poem; call it a song; call it a confession; call it a prayer. Like so much of Cohen’s work, it defied definition. Near the end, there was nothing on his tongue but hallelujah.