The words themselves aren’t so strange. Although, I have to admit, there is a hint of the Gothic to them. The word mourn is never used lightly, and nobody begins a declarative sentence with oh anymore. But you can’t really call them strange words. What is strange is that they came to me as clearly as they did.

Oh, how I mourn her passing.

That’s what they were. Those exact words. But how and why did this fully articulated phrase land suddenly in my brain, so out of the blue?

I had come to Paris for a story about Mavis Gallant, who died on February 18, 2014, and I was in the cemetery where she is buried. I had also just thrown up. I mention this last detail because the words popped into my head, without warning or preamble, immediately after.

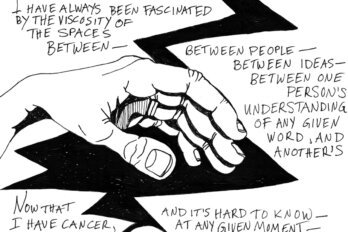

I concede that the state of my digestion may seem irrelevant. On the other hand, my experience was unusual. And the sudden appearance of the unusual is the kind of beginning that Gallant savoured. A character she did not yet know—that is, a character she had not yet fully created—might speak to her. A scene she did not yet understand might appear without explanation or context. A fragment of memory—clear, as her memories tended to be—might suddenly present itself. And on the foundation of these strange, unheralded visions, she would bring to bear her intelligence, her wit, her empathy, and her great skills as a fiction writer. Her stories are, in a way, investigations into the mysteries of their inspirations; because writing was a kind of quest, she resisted and was irritated by efforts to decode it. It was a process that she held as sacred. Unknowable.

In a 2007 interview with the Quebec cultural journalist Stéphan Bureau, published in Brick magazine, Gallant (who spoke freely in French about her work, which was always in English) described the mysterious flashes in which her stories presented themselves. They arrived at ordinary, unexpected moments. She might be brushing her teeth, she said, and something would arrive “like a dream, you know—you’ll forget it if you don’t write it down at once.”

I have to say there was something weirdly dreamlike about the words that came to me in the Montparnasse cemetery. I was feeling odd, somewhat light-headed when it happened. I was greatly relieved that I spotted the public washroom in time, and that I had some mint gum in my pocket. And then, bang: the words appeared so clearly they might have been stamped in black ink across the white and grey Paris sky. I don’t want to get carried away, but I do wonder if I experienced something beyond indigestion. Perhaps I experienced something like the visions peyote users have after they scare themselves half to death with the ferocity of their vomiting.

In the days that followed, I sat writing in a white loft with soaring ceilings in the thirteenth arrondissement. Occasionally, to escape the more uncooperative paragraphs, I crossed the Seine, via the Simone de Beauvoir footbridge, to the Parc de Bercy. A few times, I strolled as Mavis Gallant had often strolled through the Luxembourg Gardens; once, I ate an old-fashioned French lunch in the artist’s bistro Wadja, on the rue de la Grande Chaumière, as she liked to do. I drank coffee with her friend Odile Hellier on the terrace of le Dôme—the grand café Gallant most enjoyed. I stood in front of 14 rue Jean Ferrandi, her home for some fifty years, and considered the view she had when she looked up from her work. I went to le Danton on Boulevard Saint-Germain to meet Ian Paterson, the photographer whose work appears on these pages. We discussed how the personality of Paris was a part—a crucial part—of the personality of Mavis Gallant.

All the while, I couldn’t escape the notion that Oh, how I mourn her passing was important. In fact, the sentence haunted me; it was as if I had seen a ghost flitting among the tombstones of Montparnasse. But I couldn’t easily account for it—which only reinforced the notion that, as ghosts are wont to do, it bore some message. But what?

I never met Mavis Gallant. We never corresponded. I never even saw her read in public. I am not close friends with anyone who was a close friend of hers. My knowledge of her work is far from comprehensive. So who was I to be so mournful?

She is a writer I greatly admire, of course. But she was ninety-one and had not been well for some years. Because she took such pleasure in the narrow streets and the civic gardens and the grand boulevards of Paris, I thought they might be reliable clues to who she was—more reliable, at any rate, than anyone’s speculation on the carefully guarded private realm of what was a very private life.

Mavis Gallant was, by her own admission, a city girl. I remember thinking, If I can sense the delight she must have taken by strolling past shops at dusk on a lustrous spring evening, I will have a more profound sense of her. Paris became a kind of memorial for me, because her Paris was by no means a secret one. She enjoyed its bold, public gestures—a meal at le Dôme, a visit to the Jeu de Paume, a bottle of champagne, a taxi ride to see the chestnut trees in bloom. And although my retracing of her steps had an elegiac quality, I wasn’t exactly grieving. Certainly not enough to begin a sentence with oh.

On the face of it, I was simply standing in the Montparnasse cemetery catching my breath after a brief, unanticipated squall of nausea. I wasn’t even thinking about Gallant—at least not in the biographical sense. I wasn’t thinking of her birth in Montreal in 1922; nor her lonely, itinerant childhood; nor her early employment in Montreal; nor her decades as a contributor of short stories to The New Yorker; nor her friendships with such writers as Anne Hébert, Michael Ondaatje, and Alberto Manguel; nor the decline in her latter years; nor her friends’ concerns about her health, finances, and increasingly determined aloneness. (About two years before her death, she fell in her bathroom and spent more than a day on the floor before she was found.) None of these things were on my mind. I know this because—in the way we can remember dreams after we suddenly wake—I remember exactly what I was thinking about when the words Oh, how I mourn her passing materialized. I was thinking about a Mavis Gallant story called “The Remission,” which The New Yorker published in August 1979.

I didn’t choose this story in a conscious way—certainly not in the orderly, exemplary manner of an academic or critic. I may be a writer, but I am a very ordinary reader—serendipitous, idiosyncratic, undisciplined, almost careless in the way I select books and articles and stories. I may not be the last of my kind, but I am drawn from the diminishing ranks of the general reader—riders of subways, patients in waiting rooms, tourists on hotel balconies, insomniacs who reach for the magazine on their bedside table at 3 a.m. I pick things up. I read them. And sometimes, with no rhyme or reason, I fall in love. “Have you read the Mavis Gallant? ” someone must have asked me in 1979. The introduction may have been as simple as that. In my mind, she has helped to define good writing ever since.

I don’t know her entire oeuvre—far from it. In the course of her career, she published two novels, a play, and more than a dozen collections. The New Yorker alone printed 116 short stories, making her as much a fixture in its pages as John Cheever or John Updike. It is her New Yorker connection—as well as a shared literary quality—that links her with Nobel laureate Alice Munro, particularly when Canadians are doing the linking.

I’m sure that any number of Mavis Gallant’s stories fairly compare to “The Remission”: her standards wavered little from subject to subject. She thought of her work more as a string of beads than as a gathering of variances. This is largely, I think, because her relationship to it was based on a rigorous, deeply private process—not in assessing individual stories or talking about them or even reading them after the fact. “I’m not a teacher,” she complained in the Brick interview, “and I can’t analyze what I do.” She didn’t much care for stacking the themes, settings, characters, and narrative structure of one composition against those of another. “I don’t compare stories,” she told novelist Jhumpa Lahiri, a little impatiently, in a 2009 interview for the literary magazine Granta.

They were talking about “The Remission,” which captures with Vermeer-like precision an English family in a Mediterranean town. Just after World War II, they have come to “a pink house wedged in the side of a hill between a motor road and the sea” to live a little absurdly, a little unreasonably, and well beyond their means in a crumbling villa. Alec Webb—husband of Barbara and father to Molly, James, and Will—is dying. He is convinced that the little, bedraggled expat community on the Riviera will accommodate more comfortably, and with a certain panache, his sickness and death.

“Can you talk about what inspired the story? ” Lahiri asked.

“Oh, I don’t know,” Gallant replied unhelpfully, before reluctantly adding, “I just had an image of them getting down from the train.”

There was something prickly about Gallant. Her friends all mentioned this. The more they loved or admired her, the more likely they pointed out that she could be “difficult.” It’s a quality you can sense reading the interviews: She would withdraw from her initial enthusiasm as the questions unfolded. She took her work seriously—as almost all of her sentences reveal—but also saw something ineffable at its heart. She dug in her heels when asked to deconstruct a truth that she had gone to some lengths to construct. Stéphan Bureau once asked her about narrative tension, and she sputtered: “I’m sorry, but I can’t really explain.” Bureau wisely said, “No need to apologize. We understand by reading your works. You don’t need to talk about them.” In that interview, you can almost hear her breathe a sigh of relief.

By way of the general reader’s somewhat haphazard selection process, “The Remission” is the Mavis Gallant story that I have returned to over and over. I keep picking it up. Other stories might more rightly be considered her best, but “The Remission” is certainly among the reasons that one of Canada’s most astute critics, Robert Fulford, compared her to George Eliot, Henry James, and Anton Chekhov. It’s an excellent example of why the great British biographer Hermione Lee described Gallant as “a paragon and a delight, a writer of the utmost subtlety, curiosity and attentiveness.”

Oh, how I mourn her passing.

I was lost in thought when these words revealed themselves, lost because there is a scene in “The Remission” that is so vivid it sometimes feels more like a personal memory than a recollection of something I’ve read. Poor, bedridden Alec Webb—who everyone thinks is so close to death that he can’t come downstairs to watch the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II on the blurry black and white screen of a newly acquired TV—appears “gasping in the doorway, holding on to the frame.”

Gallant claimed such literary territory as hers, because she understood expatriate life well and, as a result, excelled at composing its most telling nuances. (“Details,” Manguel told me. “She was always talking about details.”) With every sentence of “The Remission,” you understand what Manguel means when he describes Gallant as a writer who possessed a good journalist’s uncompromising loyalty to reality: “She had a kind of Truman Capote memory, and what mattered to her was an accuracy that was synonymous with truth and honesty, and that therefore became an aesthetic quality.”

When Alec Webb appears gasping at the doorway, Gallant tells us that his hair “was carefully combed and parted low on one side . . . and he had dressed completely, though he had a scarf around his neck instead of a tie. He was the last, the very last of a kind. Not British but English. Not Christian so much as Anglican. Not Anglican but giving the benefit of the doubt.”

Perhaps it was Gallant’s Canadianness that allowed her to capture the English so intimately, while never losing sight of how strange they appeared to those who didn’t share in the intimacy. Her ear for this minor key was pitch perfect. At one point in the story, Mr. Cranefield, a semi-successful novelist and part of the expat community, describes the spiritual difference between the British and the Mediterranean soul by drawing upon history, sociology, and comparative religion. When it comes to revelations, he says, the English aren’t “awfully good at seeing saints . . . Though we do have an eye for ghosts.” And has there ever been a better description of the thin, broadcast voice of the new queen, which Gallant describes as “ironed flat by the weight of what she had to remember”?

You could teach a creative writing course based on “The Remission”—a prospect that would have horrified Gallant. The newfangled TV on a little stage of an unused room, which had hosted amateur theatre before the war; the chorus-like gathering of expats; the apparition of a dying man at the doorway—every detail sharpens the pivot of a specific point in time. We can argue whether or not “The Remission” is the kind of story people want to read anymore; we can wonder if the fleeting moment that Gallant inspects so carefully still has relevance; we can question the story’s marketability in today’s thumbs-up, thumbs-down critical schema; we can wonder if there are stories that better exemplify her work. But what we can’t dispute is how fantastically good “The Remission” is.

I was alone in the cemetery after a lunch near Saint-Sulpice with Livia Manera, an Italian literary journalist who knew Gallant and had written about her for Corriere della Sera, the Milan newspaper. We met at la Petite Cour, a small, civilized restaurant that Gallant occasioned with friends. “Not because we were rich,” Odile Hellier, who once owned the Village Voice Bookshop, explained. “But because we weren’t. We knew exactly what those dinners cost.” Gallant enjoyed the patio, which sits just below grade and has a gently splashing fountain. She lived nearby and, in the square-heeled pumps she favoured, often walked to la Petite Cour.

My most frequent question in Paris was, “In what way was she difficult? ” Each response had the tone of someone remembering a hugely admired, if occasionally exasperating, older sister. “It was like this,” they’d say. They’d tell me about how caustic, or cutting, or uncompromising she could be. And then they’d make me promise not to repeat their anecdote.

For example, an aspiring novelist once pressed Gallant for advice, which she stubbornly refused to give. She could have said something—anything, almost—to satisfy the would-be writer. But she wasn’t the kind of person who did that. As Hellier put it mildly, “She could be very direct.”

How to write? This was not, as far as Gallant was concerned, an uncomplicated question. It was also a question that, were it to be answered meaningfully, would require more soul-searching, more thought, more self-analysis than she would want to undertake in front of a stranger. It’s easy to imagine how the question could come across as rude or impossible to answer—or both. Besides, she firmly believed that writing could not be taught.

But the young author persisted. “All right,” Gallant finally said. “Here’s some advice: never drink cheap wine.”

And so, in honour of Mavis Gallant, Manera and I didn’t. I can’t now remember what bottle we ordered at la Petite Cour, but it went very well with the steak tartare—which was, I thought, the kind of traditional choice of which Gallant (always a traditionalist when it came to Paris) would approve of.

She has been described as a writer’s writer, a term that can deserve the misgivings that attend it. For one thing, it implies that writers are more perceptive readers than non-writers are, which is simply untrue. For another, it is praise that often carries no small amount of practical difficulty for its recipient. A writer’s writer is often a euphemism for someone who, although greatly admired by those who go to the trouble of admiring writers, has not achieved great commercial success.

In Gallant’s case, the label had an even darker connotation. Within the general, rather impractical context of earning a living by writing, Gallant was most practical. She was disciplined, hard working, and down-to-earth in her nose-to-the-grindstone approach. Nonetheless, even she ran aground on the shoals that writers most fear: a book, a story, a script that simply won’t come together. For decades, she worked on an ambitious book about the Dreyfus affair, and though the publication of her journals may reveal otherwise, the project seems to have defeated her. It was a failure that had no antecedent in a life with no shortage of challenges.

An only child, Mavis Young had a solitary upbringing and a disjointed adolescence. She was fluently bilingual by the age of three. Her father died when she was ten; she was then shunted to a succession of schools, some quite far from home, by a mother who, in Gallant’s typically mordant assessment, “should never have had children.”

Gallant liked to boast that she attended seventeen different schools during the unsettled improvisation of her education. Rather than hinder her, her upbringing bequeathed a strong sense of self-reliance. It also gave her something else: whatever the private wounds she carried about her youth, her memories equipped her with an uncanny precision for wry, unsentimental observations of kids.

In “The Remission,” descriptions of Barbara and Alec Webb’s three children would be almost peripheral were they not drawn with such sharp, detailed economy: “Since they had no school to attend, and did not know any of the people living around them, and as their mother was too busy to invent something interesting for them to do, they hung over a stone balustrade waving and calling to trains, hoping to see an answering wave and perhaps a decapitation.” Here, in a single sentence, Gallant captures the mood of boredom and exhilaration that children find when abandoned to wide gaps of time in barren, unfamiliar places.

“She found reality extraordinarily tragic, and because of that, very funny,” Manguel told me. “For Mavis, tragedy had nothing to do with seriousness.” She did not casually display the subtlety of her humour. She worked hard at it, challenging herself with standards established by those writers—E. M. Forster and Thomas Mann, for example—whom she most admired.

It was World War II that opened a professional door for her in Montreal: women could find jobs that previously had been unobtainable. She worked briefly at the National Film Board, and less briefly as a reporter for the Montreal Standard. She was married to a musician, also briefly, and took from that entanglement the sadness of experience, the certainty that she would always live on her own, and the excellent byline Gallant—pronounced the old-fashioned English way, with the emphasis on the last syllable.

In 1950, she moved to Europe with the intention of making a living as a professional writer. Not a few eyebrows were raised—most of them by her male colleagues in Montreal who were jealous, skeptical. They assumed she’d come back, looking for work, soon enough.

Journal entries from that early period of emigration—written in Spain and in the south of France—reveal a determination consisting of equal parts stubbornness and bravery. She was always poor, often hungry, and if that wasn’t bad enough her unscrupulous agent was pocketing her earnings from The New Yorker. Yet she stuck with plan A. She persevered. And as measured in the world of professional writing, she was successful. She moved to Paris, and lived there until she died.

She remained a Canadian, not so much out of patriotic pride (she didn’t put much stock in that sort of thing) as out of a conviction that being Canadian was simply a fact of life. Indeed, after eyeing her for a while with the cool, slightly hurt distance that nations reserve for their expats, Canada honoured her with awards, a university residency, a senior arts fellowship, and critical regard. It’s worth remembering that From the Fifteenth District, her 1979 collection of New Yorker stories published by the redoubtable Douglas Gibson, was passed over for a Governor General’s Award—like Robertson Davies’s masterpiece, Fifth Business, nine years earlier. But this oversight was corrected in 1982 when Home Truths, which Gibson edited, won. The previous year, Gallant was awarded the Order of Canada—an honour that was upgraded from Officer to Companion twelve years later.

Although she was not well known as a writer in France (a lack of recognition, she admitted to friends, that wounded her pride), she lived independently to the very end. In her introduction to Home Truths, she quoted Boris Pasternak: “Only personal independence matters.” She was never more than temporarily flush, but that didn’t seem to bother her much. You didn’t have to be rich to enjoy life in Paris; until relatively recently, the US dollars paid by The New Yorker went a long way. She had a favourite table at le Dôme; she loved white roses; she enjoyed a good meal. She gave occasional readings at Odile Hellier’s bookshop and at the Canadian Cultural Centre. Literary types called on her, and sometimes they’d go to la Petite Cour or Wadja. She loved walking in the Luxembourg Gardens.

Toward the end of her life, she suffered from ulcers, from increasingly debilitating osteoporosis, and from the changing times. Evolving literary tastes, diminishing attention spans, declining magazine-ad revenues, new editors, the Internet, Amazon, fad, fashion, the iPad, and who knows what else—they all affected her income. Whether it was a problem of her own making or the problem of the increasingly shallow, anti-intellectual culture, time passed her by. She was a writer who wrote for readers who paid attention. And they didn’t anymore.

As her health became increasingly fragile, and her finances more precarious, a concerned circle of friends, editors, academics, writers, and her agent, which tried to look after her, regarded her future with some dismay. Occasionally, and usually without her knowledge, SOS’s were sent to funding institutions such as the Writers’ Trust of Canada. To its great credit, the trust came to her rescue in 2000, awarding her the newly minted $20,000 Matt Cohen Award.

Despite the transformative changes in publishing, Gallant was not inclined toward accommodation. She wrote by longhand and used a typewriter. She posted letters to friends. She worked on manuscripts that she could physically hold. Tweets and blogs were not part of the carefully honed, slowly crafted language that she spent her professional life perfecting. And, of course, she was getting old. She could no longer count on being published; after 1995, there was little new work to publish anyway. But she remained stoic. “I have chosen to be a writer,” she told her anxious friends. “I know what it entails.”

This period would have been much easier for her had she been comfortably well off, but her reputation was measured on another scale. As Steven Barclay, a close friend and co-editor of her forthcoming journals, has pointed out, the fact that Ondaatje, Lahiri, and Russell Banks all wrote introductions to her collections demonstrates her stature. Fellow Canadian and three-time Governor General Award–winner Hébert was one of her closest friends. Carol Shields, Janice Kulyk Keefer, Jane Urquhart, and Susan Swan idolized her. She was, as Hellier described for me, “the last serious writer.” Mavis Gallant was, without question, one of the finest authors this country has produced. She was also close to penniless when she died.

In an obituary in the Globe and Mail, Sandra Martin wrote, “Ms. Gallant had a journalist’s nose, a cinematographer’s eye and a novelist’s imagination. She combined her technical skills and sensory perceptions in the shrewdly observed and multi-layered short story, a form she made her own. She was a specialist in writing about outsiders trying to insinuate themselves into alien situations and cultures.”

It was one of those shrewdly observed, multi-layered stories I was thinking about in the cemetery. “The Remission” explored a subject for which she possessed an unequalled eye. In the dreariness of Europe’s immediate postwar years—in the impoverishment and uncertainty, in the far-flung, uselessly dignified remnants of an old empire—Mavis Gallant saw a world in transition. It wasn’t an era so much as a sputter of one, and she caught it vividly in her sights, just before it disappeared altogether.

“The Remission” begins, “When it became clear that Alec Webb was far more ill than anyone had cared to tell him, he tore up his English life and came down to die on the Riviera. The time was early in the reign of the new Elizabeth, and people were still doing this—migrating with no other purpose than the hope of a merciful sky.”

Looking up into a sky that was more white than blue, this being Paris, I was stopped in my tracks. There I saw the words Oh, how I mourn her passing set against a radiant cloud. Not really, of course—to say that I actually saw them would be stretching it. But they were so clearly manifest in the Montparnasse cemetery that they might as well have been.

Maybe there was nothing mystical about it at all. Gallant’s grave is not an easy one to find: an attendant looked at me blankly when I asked. In fact, she’s not even in her own tomb. Her friend Josie Peron donated what amounts to a spare room in the Peron family crypt. As Manguel put it, the burial was like a turn of events straight out of a Mavis Gallant story. It was the kind of unexpected development that she enjoyed—because, as Hellier said over orange juice at le Dôme, she “wanted to know how people managed to be who they are.”

So there I was working my way, grave by grave, up and down the grid of tombstones, having made the mistake of ordering steak tartare at lunch an hour or so before. And maybe all that happened was that I thought of something someone had mentioned about the person whose grave I was looking for. I’d had interviews with her friends and acquaintances, and they’d all said the same things: That she was charming, dignified, funny, brilliant—and difficult. That she was a fiercely dedicated writer who investigated her own observations, experiences, and memories with the dogged determination and precision of a journalist. That the great love of her life was the city of Paris. That until her final years, she worked every day in the apartment she first rented in 1960, in an undistinguished postwar building on the rue Jean Ferrandi. That sometimes she wrote longhand in the kitchen, and sometimes she typed at her desk, where, when she looked up from her work, she could watch a dozen domestic narratives play out on the street below. That she had a great sense of style—and of fun. That she enjoyed gossip and mischief, and did not suffer fools gladly.

An image of Mavis Gallant had emerged from these descriptions—an image that echoed the one perfectly captured by Lahiri in 2009:

At eighty-six, Mavis remains an elegant woman. Each day she was impeccably dressed in a woollen skirt, sweater, scarf, stockings and square-heeled pumps. A medium-length coat of black wool protected her from the Paris chill and beautiful rings, an opal one among them, adorned her fingers. Her accent, soft but proper in the English manner, evoked, to my ear, the graceful and sophisticated speech of 1940s cinema. Her laughter, less formal, erupts frequently as a hearty expulsion of breath. French, the language that has surrounded her for over half a lifetime, occasionally adorns and accompanies her English. She is a spirited and agile interlocuter [sic] who tells stories as she writes them: bristling with drama, thick with dialogue, vividly rendered and studded with astringent aperçus.

But this remission from the process of shrinking and aging and declining didn’t last for long. Gallant’s hands began to seize. The physical difficulties she acknowledged in that interview (she was saddened that she could no longer visit art galleries, because she was unable to stand for any length of time), increased in the years that followed. Eventually, she was losing the two things she most cherished: her independence and her memory. This was very sad, and any of her friends might have leaned across a table at le Dôme and confessed, Oh, how I mourn her passing.

It was after my lunch with Manera that I went to the cemetery. It had been on my Paris to-do list for years. Samuel Beckett is there. Charles Baudelaire is there, too. So is Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, Guy de Maupassant and Brassaï, Man Ray and Constantin Brancusi, Marguerite Duras and Carlos Fuentes, Alfred Dreyfus. The pale city where their lives intertwined looms over the stately arrondissement.

Gallant’s funeral took place here on a winter’s day one year ago. About fifty friends gathered, many of them bringing white roses to say goodbye. It was a solemn, low-key affair.

Like Alec Webb, Mavis Gallant was the last of her kind. She is mourned by literary scholars, of course, who continue to explore the intricacies of her work. She is mourned by her friends and by fellow writers, of course, for whom she remains an example of fierce dedication and unwavering standards. But it was only months after I’d left Paris—when, without thinking much about it, I once again picked up “The Remission”—that I realized it is, perhaps more than anyone, the general reader who should most greatly mourn the passing of a writer who held the general reader in such high regard. Mavis Gallant wrote as well as she possibly could for people who would simply pick her up—casually, carelessly, without vested interest. And who would then, as general readers do, get lost in the worlds she created. The general reader, along with her beloved Paris, are what Mavis Gallant must miss of life. But that day, in Montparnasse, I hadn’t yet had this thought. I was just looking for the grave of a great writer, and I felt as if nothing was left inside me but sadness—the pain of which I could not immediately explain.

This appeared in the March 2015 issue.