wilcox, saskatchewan—Here are a few things you’ll find in Wilcox, Saskatchewan: one little store, one Olympic-sized hockey rink, one motel, three illuminated manuscripts from medieval France, three grain elevators, and one copy of the Nuremberg Chronicle—published in 1493, written in Latin and illustrated by 1,809 superbly detailed woodcuts.

Wilcox is five streets long and three streets wide; the only red lights are behind the hockey nets. Finance Minister Ralph Goodale, the town’s most powerful native son, evoked the place during his March budget speech. “In the depths of the Depression,” Goodale said, “a unique character named Père Athol Murray founded a remarkable prairie school known as Notre Dame. Murray was tough as nails but he had a simple faith . . . that an education could open doors, expand opportunities, and change lives.”

Thanks to Murray, Wilcox boasts not only an arena but also the manuscripts, the Nuremberg Chronicle, and dozens of ancient books, some of them printed shortly after Gutenberg invented movable type. They belong to the boarding school, Athol Murray College of Notre Dame—the only thing that keeps the town alive. Its 350 students far outnumber the town’s other residents.

“Amazing, isn’t it? ” says Terry O’Malley, a three-time member of Canada’s Olympic hockey team and now the school’s president. “The middle of nowhere.”

Into this nowhere, half an hour south of Regina, the hockey legend Patrick Roy sent his goal-tending son Jonathan: “Not a bad player,” O’Malley says judiciously. “But he didn’t make our top team.”

Notre Dame has been hit hard by the decline of family farms and big Catholic families across the west; today the school survives largely as a training ground for athletes. Its top teams have nurtured NHL stars like Vincent Lecavalier, Brad Richards, and Curtis Joseph. They were Hounds (as of Heaven). On the school’s website, the Hounds’ scores are among the lead items.

Athol Murray would have approved—up to a point. He loved competitive sports. But having worked in journalism and law before entering the seminary, he also had a wide range of other interests. Since his death in 1975, a few writers have depicted this irascible, generous, domineering, hard-drinking man as a near-saint. As he would have been quick to say, he was nothing of the kind. When the governing CCF created Canada’s first medicare system in the early 1960s, Murray’s conservative rhetoric grew so inflamed that the RCMP considered jailing him for trying to incite a riot.

He was, as Goodale said, unique. The scion of a rich Toronto family, a grandnephew by marriage of Sir John A. Macdonald, Murray was educated mostly in Quebec. Exposure to the collèges classiques gave him an abiding love for Greek and Latin classics as both the foundation and the pinnacle of our culture.

Sent out to Saskatchewan in 1923, Murray fell in love with the place—and with the opportunities he could create there. Becoming Wilcox’s parish priest in 1927, he also took charge of its tiny Catholic school, expanding it into both a high school and a college. Murray had high ambitions for his charges. To be able to offer young men and women a BA in liberal arts, he persuaded the University of Ottawa to grant Notre Dame status as an affiliate. Still, Notre Dame’s public emphasis was on the body, not the mind. Its football teams took on squads from American universities; its hockey players would battle for Canadian junior championships. “Battle” was not always just a metaphor.

Whatever the students could afford, they paid. If a farmer’s son could provide only oats and potatoes, so be it. Murray refused to seek help from governments. As late as 1957, the Star Weekly called Notre Dame “Saskatchewan’s shack college.” Its low brick buildings are relatively recent; for decades the students lived in shabby cabins free of indoor plumbing. Murray’s students grew intimate with hunger—they would kneel to pray for food. Occasionally, with Murray’s tacit approval, they stole milk and chickens from neighbouring farms.

Yet to satisfy the University of Ottawa, Notre Dame needed more than illicit poultry and triumphs on ice; it needed a library. Among his other attributes, Murray was a bibliophile. No one is sure how he equipped Notre Dame’s library with vintage texts that would be the envy of most universities. But equip it he did. Books from Lübeck (1483) and Venice (1481). Leatherbound volumes signed by a French count and a Spanish marquis. A Latin text published in Lyon in 1547: Treatise on Evidence for Murder. . . .

Soon after Murray’s death, Notre Dame reverted to being just a high school. History and foreign languages are not prominent on today’s curriculum; the classics are absent. Murray’s collection survives inside a locked vault in the school’s museum. Students rarely glimpse the ancient books; their working library is a nondescript room tucked behind the hockey rink.

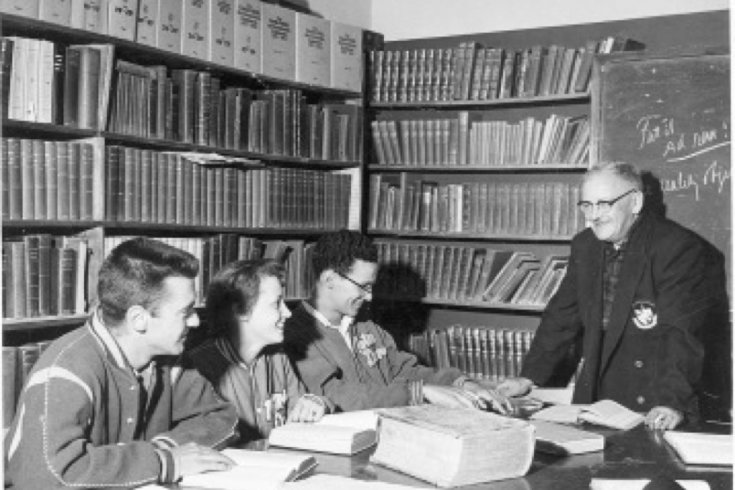

To reach the rare-book vault, you have to walk past a maquette of the ramshackle college of 1939, Murray’s moth-eaten buffalo coat, a plaster copy of friezes from the Parthenon—and several cans of Spam. (They commemorate a hungry moment when Murray advised the students to pray for a miracle. The next day a boxcar full of Spam arrived, courtesy of John Diefenbaker.) The vault forms an inner sanctum. Except on organized tours, few people venture in. The Nuremberg Chronicle and other rarities survive behind glass; humidity, light, and temperature are regulated with care. It’s a far cry from past decades when, in the midst of a lecture about Martin Luther, Murray would run out of the classroom and reappear waving a 1569 edition of Luther’s Bible.

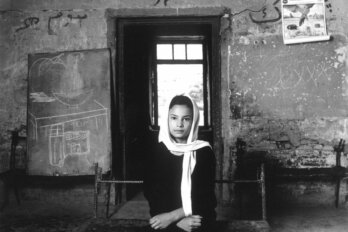

“When Père was here, it was all hands-on,” says Jean Nelson, the archivist and museum curator. She has hauled into the prairie light a jewel of his collection: a thirteenth-century manuscript glorifying France’s patron saint, Martin of Tours. The manuscript is made of vellum—supple parchment from a calf’s belly. Look closely and you can still detect the lines that some anonymous scribe ruled across each page. The scribe then copied the saint’s miraculous deeds in double columns, leaving a space atop each section for a splendid ornamental initial.

These initials twine across the page like vines. One of them encloses a tiny portrait of a chunky, open-mouthed man brandishing a stick. It bears a striking resemblance to Murray.

In all likelihood, this manuscript arrived in Wilcox from Gull Lake, Saskatchewan, a small town about 250 kilometres to the west. Gull Lake was the parish of an expatriate French priest named Al Bacciochi—a distant relative of Napoleon who had previously worked in Louisiana. He didn’t slap his name on any manuscript. But he signed an illustrated 1637 edition of Ovid’s Metamorphoses. And on the title page of a magnificently illustrated Bible from 1874, Bacciochi wrote: “I am so glad to deliver into your hands, Father Athol Murray, the Bible [by] Gustave Doré the greatest illustrator of our times. I know you will enjoy it, admire it.”

The only study of the school’s collection—a recent thesis by Michael Santer of the University of Saskatchewan—mentions more than 450 items. About many of them, little is known: a parchment decree, for example, written in Latin and signed in the name of James I of England in 1606. Santer noted tersely, more work is needed.

“There’s a bit of a mystery here,” Nelson says, “but there’s no money to solve it. You’re living on what the kids bring in.” She gazes at a Latin letter, bound or trapped inside a first edition of Erasmus’s Institutio principis Christiani (“Education of a Christian Prince”), published in Basel in 1516. Its calfskin cover is peeling away, half exposing the letter. Who wrote it? Who received it? What news did it convey?

In truth, there are numerous mysteries about Murray’s ancient treasures in the middle of nowhere. “We’ve got things here,” Nelson admits, “that we don’t know we have.”