Two months ago, a group of scholars, activists, and artists converged in Toronto to help celebrate the 20th anniversary of Rinaldo Walcott’s seminal treatise on Black Canadian culture, Black Like Who? In his groundbreaking book, Walcott insists that “Writing blackness is difficult work,” particularly in Canada where “we are an absented presence under erasure.” The erasure Walcott describes occurs because black people in Canada are too rarely seen as truly Canadian. As such, Walcott argues that “blackness in Canada is situated on a continuum.” That is, black people are either erased from Canadian history and identity or they are “hyper-visible”— representing a criminal, unruly population that must be kept at a safe distance.

While discussion at the conference centred around Walcott’s book, there was also ample talk of how little had changed in the twenty years since its publication. Despite the many achievements of black authors and scholars—many of whom were in the room—black culture and writing continue to play a marginal role in Canadian literature.

To date, the New Canadian Library—a series of “classic” works of CanLit—contains one entry by a black author: Austin Clarke’s Amongst Thistles and Thorns. It was added in 1999, more than thirty years after its publication and long after his contemporaries had secured their place in the canon. Where writers such as Mordecai Richler, Margaret Atwood, and Alice Munro merit courses, biographies, and books dedicated to their writing, black authors are typically relegated to a single poem or short story at the tail end of a CanLit class.

Likewise, major Canadian anthologies are still being printed that either exclude important black Canadian writers or that offer the token inclusion of a single poem or short story. Scan CanLit syllabi and you’ll see the same go-to figures—Dionne Brand, say, or Marlene NourbeSe Philip—who are often made to stand for the entirety of Black Canadian literature, casting that body of work as newer and narrower than it actually is.

So it wasn’t entirely a shock when, several days after the event for his book, at a conference called TransCanada, Walcott announced that he was “quitting CanLit.” He will no longer be attending conferences on CanLit, writing about CanLit, or working on trying to get CanLit to recognize black Canadian writing. He went on to explain why:

“CanLit fails to transform because it refuses to take seriously that Black literary expression and thus Black life is foundational to it. CanLit still appears surprised every single time by the appearance of Black literary expression and Black life. Because Black expression is reduced to surprise there has been no sustained and ongoing serious consideration of Black work in CanLit. You can write the same essay over and over again and no one will notice.”

While some of Walcott’s colleagues at the conference responded to his excoriation with the promise that “things will change” and “we need your voice,” he appeared tired of attending yet another conference where he was one of the few black faces. He wasn’t alone. Throughout the conference, younger scholars attacked the implicitly white “we” often invoked by CanLit’s academic old guard and called for a complete transformation of the academy. One of the bigger issues is that CanLit, in many ways, is a gerontocracy; this, in tandem with the corporatization of universities, has led to the replacement of full-time positions with sessional instructors. There are fewer full-time, secure positions from which scholars can unsettle the status quo.

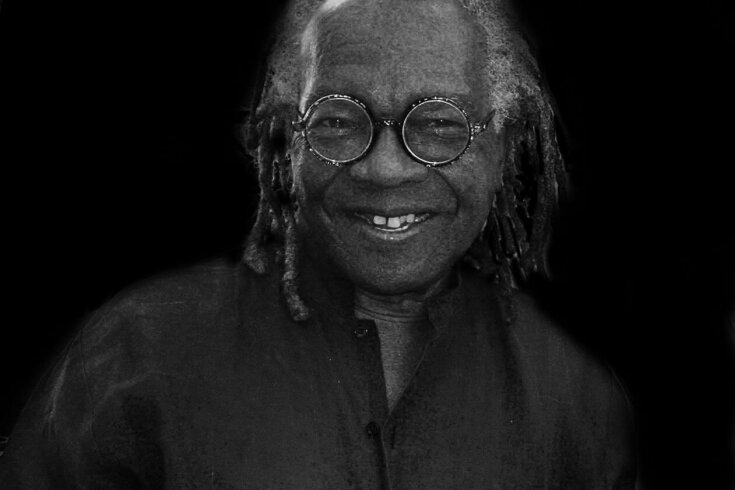

Walcott’s frustration with the lack of “sustained and ongoing serious consideration of Black work in CanLit” became clear for the four of us on the day we ventured to Ryerson University to convene our panel for ACCUTE, the annual conference of scholars of Canadian Literature. The title of our panel was “Austin Clarke’s Critical Neglect” and it posed the question of why Clarke remains such an unrecognized figure in Canadian classrooms and in Canadian scholarship. This, despite writing eleven novels, two books of poetry collections, numerous short story collections, and winning the Commonwealth and Giller Prizes. Indeed, there is an unfortunate parallel between the characters Clarke writes about, who are relegated to the margins of society, and their author, who has been largely ignored by critics.

As Walcott observes, many of our CanLit colleagues are regularly “surprised” by Clarke’s staggering contributions. Simply put, they are surprised because they have typically not read his work. While some attribute this to what they see as sexism and outright misogyny in Clarke’s writing, other writers who have faced similar criticisms—such as Richler and Layton—continue to enjoy a robust critical audience. Clarke was one of the first writers to call out CanLit’s whiteness, so his work is particularly relevant to helping us wade through the current debates. Moreover, as a writer who commented on police brutality in Canada, his observations are as urgent as ever. We therefore hoped that this panel would offer an opportunity to both reexamine Clarke’s writing and also use his work to reflect on the current challenges facing CanLit.

How many of our colleagues attended our panel? Zero. No one turned up. Given Clarke’s marginalization, a low turnout wouldn’t have surprised us. But when you consider that this was the biggest ACCUTE conference to date and that a large portion of the CanLit community had convened in Toronto, then that empty room was yet another example of black writing’s invisibility in the Canadian canon. And when you take into account the recent success of black writers such as Lawrence Hill and André Alexis, it’s become clear that the Canadian critical establishment is failing to keep pace with a public who are buying, reading, and celebrating black writers.

Why the ongoing neglect? Clarke himself provides something of an answer. In a letter dated September 4, 1980 to his friend and fellow novelist Sam Selvon, he writes: “You have to be born here, preferably on a farm, and you have to write about growing up with cow-dung betwixt your toes, in order to be taken seriously by those people who think they know about writing and literature.” Clarke’s observation is, in part, confirmed by Nick Mount’s recent book on the story of Canada’s “literary awakening” during the sixties, Arrival. Mount’s book is an excellent analysis of the period, but it’s hard to miss the fact that little has changed. The white authors who kicked off what we continue to think of as “Canadian literature”—Margaret Atwood, Alice Munro, Mordecai Richler, and Leonard Cohen—remain the figures that define the field and drive the scholarship. CanLit is still very much an anti-black space.

Of course, this essay is not merely about Clarke, nor is it simply about our panel. Many panels at academic conferences are poorly attended and we may have simply been the unfortunate victims of poor scheduling. Yet we believe our experience is particularly instructive because it reveals how the promise of CanLit—to offer a space for black voices—has failed to be kept. To move forward, CanLit must take seriously the challenges being made by black scholars and writers. This is partially about access to resources: welcoming scholars who will reinvigorate the field with new questions and ideas. This is also about challenging old conceptions of the canon to include the books of Austin Clarke—as well as of George Elliott Clarke, Suzette Mayr, Afua Cooper, David Chariandy, Nalo Hopkinson, Dany Laferriere, Wayde Compton, Tessa McWatt, and Claire Harris. These writers and their works are not marginal to our literature; they are our literature. How can one teach Canadian literature without them?

Shortly before the publication of this article, ACCUTE contacted us about our panel’s lack of attendance and the social media attention it garnered. They outlined possible contributing factors and suggested opportunities to continue the conversation about race and CanLit. We welcome their outreach, but we also know that repeated incidents of exclusion followed by calls for “conversation” are exactly what brought us to a moment where scholars like Walcott see quitting CanLit as a necessary course of action.

But while we understand Walcott’s frustrations, we believe CanLit is worth fighting for. What is urgently needed is sustained scholarly engagement with black literary expression in Canada. In this regard, we take inspiration from Black Lives Matter’s slogan describing its work against the erasure of black histories: “May we never again have to remind you.” May we never again have to be reminded that black literature is part of Canadian literature and that CanLit must rid itself of its anti-blackness. Or, in Austin’s words: “One o’ these days, they going remember who I is, and when that time come, they will do the right thing, ‘cause God don’t like ugly.”