In September 2012, two conservation officers with the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources were waiting along a dirt road in rural south-central Ontario for the poachers to emerge from the forest. The summer before, officers patrolling the area had stumbled upon a poached patch of wild American ginseng after noticing shallow holes pockmarking the ground next to discarded plants torn of their roots. In some spots, though, the stems and leaves had been neatly tucked back into the soil as if to cover up the massacre. The plants were now the standing dead. Nearby, the officers noticed a clue: lying face up on the forest floor, half-shaded by sugar maples, the red of an empty pack of DK’s cigarettes flickered in the scattered sunlight.

Federal and provincial authorities launched an operation to catch the poachers. With Jean-François Dubois, a federal wildlife-enforcement officer, the team installed motion-sensor surveillance cameras, dispatched patrols, and even marked the roots with a special ultraviolet, traceable dye. When the two patrolling officers peered through a truck’s window, they spotted a pack of DK’s lying on the seat. It wasn’t long before Michael Allison and Russell Jacobs hiked out of the trees carrying backpacks brimming with 253 poached ginseng roots that could have fetched a quarter-million dollars.

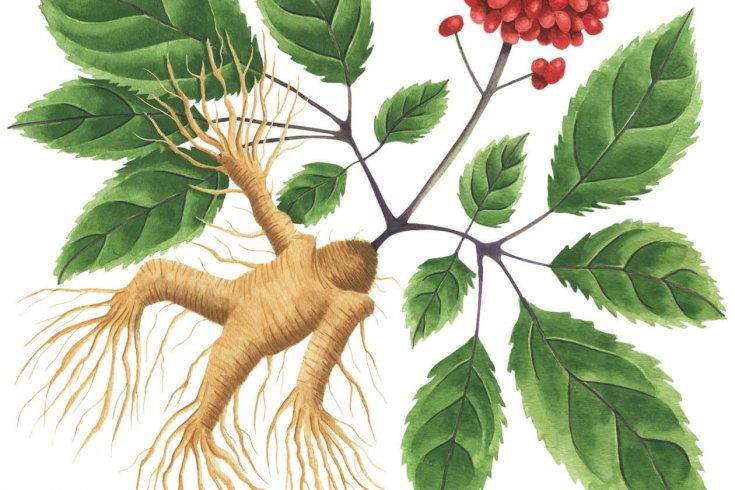

Wild American ginseng, or Panax quinquefolius, thrives in subtlety. Its willowy stem with finely serrated green leaves rarely grows above knee height, and its ghost-white flowers blend in more than stand out in a forest’s understorey. The easiest time to find the herb is in late summer, when it bursts with blazing crimson berries, a siren song to poachers who scour the forests of Ontario and Quebec for the elusive and valuable plant. A pound of wild ginseng root can fetch $1,000 or more on the black market for use in traditional Chinese medicine. Since 2008, wild ginseng has been listed as endangered under the Ontario Endangered Species Act and as threatened under Quebec’s Loi sur les espèces menacées ou vulnérables since 2001.

According to Interpol, the movement of wildlife products is now the fourth-largest illegal trade in the world, behind drugs, humans, and counterfeit currency. Poaching and trafficking are exploding as prices soar. “In South Africa in 2007, there were thirteen rhinos poached. In each of the last five years in a row, it’s been over 1,000 [annually],” says Sheldon Jordan, director general of wildlife enforcement for Environment and Climate Change Canada and former chair of Interpol’s Wildlife Crime Working Group. Poachers around the world are after everything from rare timber to exotic bird feathers. Between 2009 and 2013, the average price for polar bear pelts more than doubled.

In the past decade, the Canadian government has gone to extraordinary lengths to protect species, employing nearly eighty enforcement officers across the country and coordinating international operations to catch perpetrators. In 2016, officers conducted more than 3,500 inspections and hundreds of investigations. In March 2018, a Canadian advocacy organization launched a petition asking Canada to end the sale of elephant ivory, which to date has received more than 245,000 signatures. “A lot of the factors driving demand for charismatic animals coming out of Africa are [also causing] an increased demand in Canada,” says Jordan. The year before, a former RCMP officer was sentenced to five years in prison for laundering money procured by smuggling narwhal tusks out of the Arctic. And, a few years back, Jordan and provincial officers dismantled an eighty-person ring of bear-bile poachers and traffickers in eastern Canada. “One of the things about Canada and having so much wildlife,” he says, “is that it’s a big country to patrol.”

But the threat to wild ginseng reminds us that it’s not just parts of elephants, bears, and tigers feeding our gluttonous appetites. If the illegal wildlife trade values both large and small, both charismatic and uncharismatic, why, then, don’t we?

“It’s not a ghost anymore,” Dubois thought the day he stumbled upon his first wild American ginseng plant in Quebec. “It took me five or six years to find,” he says. Back then, in the mid-2000s, Dubois was a keen botanist, and he noticed, to his dismay, that there were no more than ten ginseng plants in this patch. Biologists can say with certainty that it takes precisely 172 plants for a ginseng population to be viable in the long term. That’s because they’re slow seed dispersers, taking seven years to reach reproductive maturity and begin flowering. “I was always in love with that plant,” Dubois says. He became a federal wildlife officer nearly ten years ago so he could enforce Canada’s Species at Risk Act and has since found dozens of ginseng clusters around Quebec, but only one reached that critical threshold.

Ginseng is no snake oil. The Asian variety has been in use for thousands of years in China, where it served as a symbol of divine harmony and later developed a reputation for potent medicinal qualities. Unlike other trafficked items today, including rhino horn and tiger bone, ginseng’s positive medical effect has been well documented in scientific studies. “It’s a panacea, a cure-all,” says Edmund Lui, former scientific director of the Ontario Ginseng Innovation and Research Consortium at Western University. Wild American ginseng can reverse the conditions that lead to heart failure, and it can control metabolism and manage obesity; it can help with erectile dysfunction, modulate blood glucose, and prevent kidney damage and cataracts; it combats toxins in chemotherapy, is an anti-inflammatory, and can reduce some effects of aging. “A lot of people underestimate the virility and the strength of [ginseng],” says Lui.

Indigenous people have long used wild ginseng found on this continent to treat headaches, earaches, convulsions, bleeding, fevers, vomiting, tuberculosis, and gonorrhea.

During the colonization of North America, the wild ginseng trade was second only to the fur trade in New France. Some early settlers even abandoned their fields to harvest ginseng in the forest instead. In the late 1800s, in a field near Waterford, Ontario, the first cultivated ginseng farm appeared in Canada, sparking an industry that eventually turned the country into the largest ginseng cultivator in the world, with annual exports recently valued at $228 million. And it’s all perfectly legal. Workers harvest cultivated ginseng after just three years, but its wild counterpart is often left to grow for decades, contorting into all sorts of gnarled and alluring shapes. Ginseng roots bearing similarity to the human form, two legs and two arms, fetch high prices. But growing the plant is a finicky practice, requiring fungicides and fertilizers that later appear in the roots. So, for many customers, ingesting cultivated ginseng is a poor substitute. Although Canada ships more than 2.5 million kilograms of cultivated ginseng to Asia each year, a black market for the wild variety continues to thrive.

In the past century, wild American ginseng has faced myriad threats, including suburban development in Ontario and Quebec that keeps destroying its habitat, and the invasion of exotic garden slugs introduced from potting soil and nursery plants. Though it knows the regions where the plant grows, Canada’s wildlife-enforcement directorate still isn’t sure exactly how many populations exist in the country. “Because it’s so endangered, we don’t know where it is,” says Jordan. When the species was last surveyed, in 1998, 50 percent of ginseng populations in Ontario showed signs of human harvesting, as did 15 percent of populations in Quebec. It’s estimated that there are between 50,000 and 100,000 plants in Canada, but only nine of the known populations in Ontario and fifty-four populations in Quebec are considered viable. Now it’s possible to be charged just by touching wild ginseng.

Customers in Asia buy nearly all the ginseng Canadians cultivate and all the wild ginseng from the legal American trade, where nineteen states permit its harvest and export under strict regulations. But Dubois says poachers are beginning to infiltrate protected areas in the United States by foraging in national parks. “That means they’re not finding as much on state and private lands,” he says. And that means prices will go up—feeding the lure and demand.

Allison and Jacobs were arrested with their valuable haul, and the two men ultimately pleaded guilty in the Ontario Court of Justice to harming and harvesting wild American ginseng; they paid a combined $9,000 in fines and were barred from returning to the area for ten years. It was one of the biggest prosecuted ginseng-poaching cases in Canada.

Dubois keeps working to catch others, and he spends summer days looking for new ginseng patches and marking roots with dye. He also continues to return every year to that same forest where he made his first discovery. The patch, against all odds, is still there—but the number of plants is going down. Wild American ginseng, in its subtlety and fragility, is a reminder that even the smallest of species has a very big role to play. Scientists are only just beginning to realize the full extent of the plant’s medical potential. “If we lose those wild populations, maybe we’ll lose something bigger than just a plant,” says Dubois. “The forest will be affected. The ecosystem will be affected. Maybe we will lose a drug that can save lives.”