I didn’t experience truly brutal winters—the ones where your teeth rattle and face aches—until my first in Toronto in 1997. Having grown up in Beirut and Cairo, and despite eight years in England, I was ill-equipped to survive Canada’s extreme temperatures. I had never heard of a “parka” until my outdoors-loving roommate showed me one and I couldn’t imagine anybody wearing something so heavy and unshapely. After the first cold snap, I slipped on icy sidewalks, and my ears nearly froze when I ventured out on a minus-20 morning without a hat.

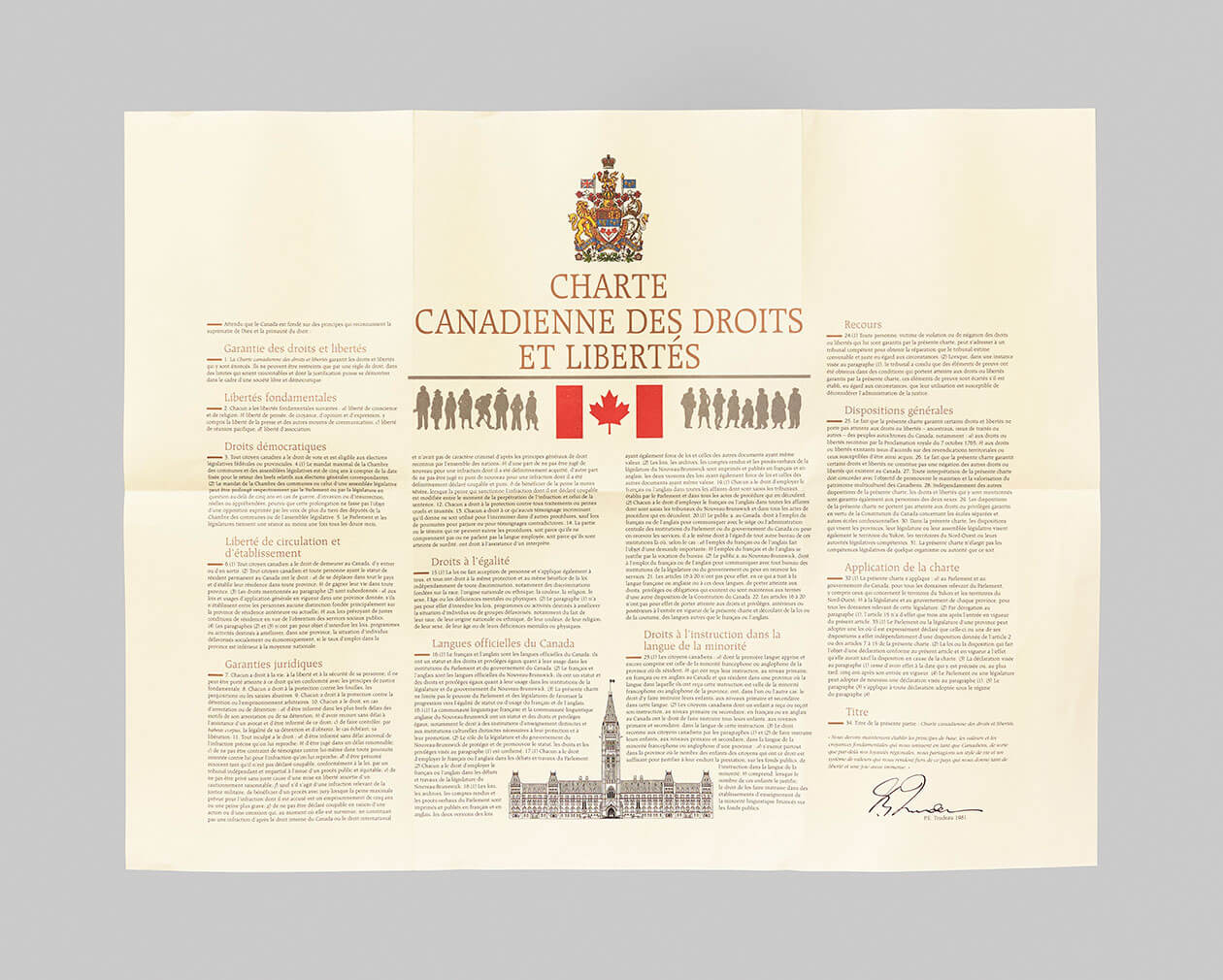

How comforting, then, to know that the first batch of government-sponsored Syrian refugees probably spent their first winter without worrying too much about keeping warm. Upon their arrival, starting in December 2015, from camps in Jordan and Lebanon or Turkey—where many had languished for years—officials distributed a grab-bag of items. The so-called arrival kits, which were later furnished to more than 25,000 refugees targeted to be flown to Canada, included parkas and jackets for youths and adults, two-piece snowsuits for children, and a one-piece version for infants. There was more: socks, gloves, mitts, snow boots, and two sets of toques (one with a Parks Canada insignia). Along with the winter gear, refugees were also handed children’s books and a copy of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedom in English, French, and Arabic. Lastly, there were National Film Board DVDs loaded with short films.

Refugee kits have been a traditional response to migrant crises, especially on camp sites, for some time now. Their history goes back to the First World War when the Canadian Red Cross oversaw the collection and distribution of food parcels, packages of “comforts” (sweaters, socks, or scarfs) and medical supplies for prisoners of war.

In the United States, several charities and aid organizations have continued the tradition, handing kits to refugees who arrive into the country with “few belongings, a difficult past and high hopes for the future,” as the leading outfit among them, World Relief, tells supporters when soliciting donations. That’s one side of America. The other, in plain view since President Donald Trump’s inauguration, is about closing its doors to those fleeing war and famine, under the guise of security and border control.

The full implications for international relations and refugee resettlement after Trump’s executive order barring immigration (and re-entry for some green card holders) from seven, mostly Muslim countries—including my country of birth, Yemen—will become clear over next few weeks. But Trump’s de facto Muslim ban has cast the current Liberal government in an even more positive light. Indeed, with each day of Trump’s presidency, the Trudeau government’s arrival kits emerge as a potent symbol of the widening humanitarian gap between the two countries.

The Liberal government’s selection of items suggests a long-term investment and hints at all that’s decent and level-headed about Canada’s relationship to newcomers—at least during the welcome stage. Had refugees arrived six months later, during the summer, the warmer weather might have made their transition easier, but any kit would have been robbed of what made it truly Canadian.

Surviving a winter, after all, is the first test toward becoming one of “us.” Whenever I meet newcomers who tell me they’ve landed in this country during the winter, my immediate reaction is to advise them in the art of layering. These kinds of survival tips have been passed on from older to newer Canadians for centuries. They shape an important lesson of Canadian resilience: The country doesn’t come to a standstill when the temperature dips. A severe snowstorm may interrupt daily routines—cancelled school buses, rescheduled events—but life goes on.

During a recent visit to Fort McMurray that coincided with the season’s first snowfall—in mid-October, mind you—I witnessed Somali Canadians carry on with their routine of meeting at the Tim Hortons on Hardin Street, their unofficial community centre. Not even the harshest days in January, one of them said, dissuades his friends from driving or walking to get their double double. His tip to me, the Toronto writer who underestimated Alberta’s weather? Leather and not knit gloves. “We’re here to stay,” says Majd AlAjji, a Syrian refugee who arrived in Calgary in August of 2015. “We must fully adapt to the new environment—just like any other Canadian.”

There’s another endurance test that we have come to call the Canadian cultural identity complex. We live in a country that, by and large, relegates the work of its artists—especially film, stage and TV—to secondary status. On average, and excluding Quebec, Canadian films account for 1 to 2 percent of total box office receipts in this country. The inclusion of a DVD of short films by the National Film Board of Canada, therefore, serves a bigger purpose than keeping Syrian kids entertained. For one thing, the DVD selection includes one set in English, another in French and a third without words. Nothing illustrates Canada’s commitment to bilingualism and inclusion as strongly as providing a third alternative that eliminates the need for both official languages.

The NFB, which opened its doors in 1939, has not only reflected Canada back to Canadians but shaped the identities of both country and its citizens. Over thousands of shorts and documentaries—many shown in schools across the country and forming part of a collective childhood experience—the NFB has championed Canadian storytellers and dreamers whose images capture the changing story of this land. My first winter in Canada was made a little less isolating and impoverished when I landed a one-off contract from the NFB to translate the Arabic-language portions of a documentary about feminism and Muslim women by a Canadian director of Arab heritage. As a newbie, I couldn’t understand what exactly made this film Canadian. It wasn’t long before I realized that the NFB’s definition of Canadian-ness meant something broader and more diverse than what the rest of the national media offered.

As Syrian children marvel at the visual poetry of Gilles Carle’s 1962 mainly wordless evocation of skating fun in The Rink, their parents might have the first of many conversations about public funding for the arts in a country that’s all but culturally swallowed by the United States. It won’t be long before the refugees start chanting the Canadian mantra of telling our “own” stories. Or will they instead demand that the country reflect its taxpayers? It’ll depend on which end of the political spectrum the new Canadians feel at home in. Will they align themselves with nationalists who believe in the role of art and public institutions (NFB, CBC, libraries and universities) in fostering an informed citizenry? Or will they jump on the train of the Ford Nation, as other immigrants have? On that train, public funding for Canadian arts represents elitism and a hijacking of the true public agenda: subways, subways, subways.

Each kit also included a copy of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, in English, French, and Arabic. Although my command of Arabic has deteriorated, I’m a native speaker, so reading the Charter in the same language that many refugees understand sent chills down my spine. Most of the rights enshrined in it—especially mobility, legal, and equality—are still unthinkable in much of the Arab world and certainly in present-day Syria. Although the war in Syria didn’t start on sectarian grounds, it quickly evolved into one where Shiite and Sunni Muslims killed each other, sometimes for territory, most often just for survival. In clear and decisive language, the Charter marks the sweet spot where freedom of religion and freedom from religion meet in Canada. Its opening words hit on both the divine and the secular: “Whereas Canada is founded upon principles that recognize the supremacy of God and the rule of law.”

Some Canadians on the political right doubt whether the refugees can ever live up to the ideals of the Charter. We’re not immune to calls of closing our borders, conflating refugees with terrorists or pleas to look after our own first, the kind of sentiments that, in part, led to Britain exiting the European Union or the rise of the far right in continental Europe and the United States. The election of Trump on an anti-refugee and anti-immigration platform suggests that the Trudeau government will have to part company with the US when it comes to maintaining a more inclusive North America. As our officials scrambled on the weekend to determine if Trump’s travel ban applies to Canadian citizens who hail from one of the seven targeted countries, Trudeau sent out a carefully worded tweet that affirmed this country’s commitment to refugees and plurality but didn’t comment directly on the executive order: “To those fleeing persecution, terror & war, Canadians will welcome you, regardless of your faith. Diversity is our strength #Welcome to Canada.” For how much longer the refugee welcome mat will be extended may depend on the next opposition leader and not the current prime minister, however.

Less than one year after the first set of refugee landings in Canada, Kellie Leitch—one of three frontrunners in the Conservative Party leadership race—was already proposing a citizenship test for all new immigrants to ensure that they share Canadian values. A day after Trump’s win, Leitch posted a note on her Facebook page and sent emails to her supporters welcoming the news as “an exciting message” that needs to be delivered in Canada as well. “It’s the message I’m bringing with my campaign to be the next Prime Minister of Canada,” she wrote. “It’s why I’m the only candidate for the leadership of the Conservative Party of Canada who is standing up for Canadian values.”

Forty-eight hours after Trump’s executive order, Leitch still hadn’t issued a statement about it one way or another. Neither had businessman and TV personality Kevin O’Leary, who entered the leadership race on an economically conservative (“jobs, jobs, jobs” as his priority) and populist (“What I’m worried about is the Canadian people”) agenda, as he explained to his former employee, the CBC. Maxime Bernier waited until Sunday afternoon to send a series of tweets that repeated his business-focused immigration platform: “More eco[nomic] immigrants, fewer refugees and family reunification.”

Leitch’s concept of a singular value system that 36 million people must abide by is lunacy. But if anything comes close to articulating this country’s aspirational vision, it’s the Charter. A mere thirty-five years old, it has already acquired the weight of a centuries-old holy book. Like Canada itself, it may feel like a done deal, but it remains a work in progress. The equality of all citizens regardless of their ethnic origins or religious beliefs remains elusive. Indigenous peoples still lag behind the rest of population in education, services, and access to clean water and fresh food. And racial profiling of minority communities and Canadian Muslims has been facilitated by a series of “tough on crime” and anti-terror laws that violate the spirit of the Charter. (Bill C-51 comes to mind.)

While Canadians who identify as black make up about 3 percent of the general population, they account for 10 percent of the federal prison population, according to a 2016 report by the federal watchdog for the Correctional Service of Canada. Indigenous communities represent 4.3 percent of the general population but 24.2 percent of the federally incarcerated. Winter clothes will protect refugees from the cold, but the Charter may not always shelter them from political headwinds or institutional racism.

The kit was a confirmation of a collective humanity; it sent a strong message about our place in a world where other nations closed their borders to refugees. It remains to be seen if Canada (and Germany under Angela Merkel) will become more isolated in the wake of increasingly nationalist, anti-immigrant governments and parties in Europe, the US, and Australia. But I remain optimistic. Two decades after landing as an immigrant, I’ve never been more convinced that it’s the best country in which to live, work, and raise a family, no matter where you come from, what god you worship or what colour your skin happens to be. The kit has taken me to my own moment of arrival into a world before 9/11 and before being Muslim became code for collective racial and political anxieties in North America and Europe.

The recipients of the kits are no strangers to terror. They have suffered more from it than anything we in the still-safe and generally stable West have ever experienced. The kit is a nod to a kinder Canada and to the harsher world we live in. I like to think that it can help replace much of what the refugees have left behind: the right to a place they can call home, where they can walk the streets feeling warm, safe and, in time, start over.