After a series of returns to my hometown over a fifteen-year period, a trip in 2017 confirmed a truth I’d been avoiding: Hong Kong did not feel like the same place I had known as a child. Between failed attempts to get by with my faltering Cantonese and an inability to recognize the once-beloved neighbourhoods that had defined my childhood, I felt like a stranger in my own home.

On my last day, after saying goodbye to my grandparents in their apartment, I looked back at them standing by their door. They seemed frail and dejected, and my grandfather turned away while holding back tears; ever since I moved away, I had felt we shared a mutual understanding that each goodbye could be the last time we would see each other. The painful memory would often reappear whenever I reminisced about my time in Hong Kong. I’d try to avoid feeling nostalgic at all, because I didn’t want their pained faces polluting my happy memories of home.

Since that time, people have been leaving the city in droves. After a wave of protests against national security legislation in 2019, Hong Kong experienced a steep population decline. Thousands of residents have emigrated to places like Taiwan, Canada, and the UK in recent years. I wonder if, like me, they wax nostalgic about a home they no longer recognize.

Nostalgia, or the act of longing for something from the past, has always seemed more bitter than sweet to me. In the years following my move from Hong Kong to Canada, reminders of the place I once called home came with a fear that my connection to it was fleeting or, worse, lost forever. I can’t help but continue longing for something I can never get back.

I’m not the only one who sees nostalgia as a double-edged sword; many cultures have tried to capture the unreachable nature of this feeling. The Portuguese word saudade was defined by poet Teixeira de Pascoaes as a desire for something beloved “made painful by its absence.” In Ethiopia, a whole genre of music called tizita is dedicated to evoking feelings of lack and longing. The German word sehnsucht is described as bittersweet yearning for something practically unattainable, like a former flame or a far-off place. The nostalgic experience seems common: a 2006 study showed that over three quarters of participants felt nostalgic at least once a week. Another study showed that across eighteen countries spanning five continents, most agree that reminiscing about the past sets the perfect stage for a range of feelings, like warmth, sadness, comfort, and regret, to surface at the same time. As someone who longs for something that no longer exists, I’m tempted to see nostalgia as a recipe for misery. But every time I indulge in nostalgia, I find it serves a purpose, even if I know I won’t be satisfied.

Nostalgia is understudied in neuroscience, but in recent years, a handful of studies have suggested that when we’re nostalgic, we also engage the same regions of the brain that are associated with reward seeking. Some research has shown that rats will repeatedly electrocute themselves to explore and seek the possibility of a reward. When we’re faced with nostalgic stimuli, like seeing a picture of a loved one or listening to a favourite song, the same brain regions that are sensitive to rewards such as food and drugs are also activated. Once triggered, they release dopamine, one of the brain’s “feel-good” neurotransmitters that gives us pleasure and satisfaction, motivating us to pursue a reward over and over again. While this explains why nostalgia can be addictive, I needed to know if it truly serves a purpose in our lives.

Neuroscience gives us some clues as to why we chase nostalgic experiences, but most of our insights come from psychology. “[We] tend to feel nostalgic when we’re in a situation that is subpar to what we want our situation to be,” says Felipe De Brigard, professor of philosophy, psychology, and neuroscience at Duke University, North Carolina. Research shows that many of us turn to nostalgia in times of distress, but while it helps us cope with bad moods, loneliness, and feelings of existentialism, not everyone reaps its benefits equally. Too much longing for the past has been linked to a heightened sense of anxiety and depression in people who are prone to habitual worrying and those coping with complicated grief or being displaced from their home country. The strongest case against nostalgia is one that could affect us all: if our end goal is to actually return to a particular point in time, nostalgia becomes a game we can’t win. As author Melissa Broder once wrote, longing is like “little treadmills of hope in the abyss,” even if it takes us nowhere. Even if she got what she was longing for, Broder said, she would have “kept looking.”

This rang true for me after watching Past Lives, a 2023 film directed by Celine Song that captured my disappointments. The story centres around Nora, a New York–based Korean immigrant who reconnects with Hae Sung, her childhood sweetheart, two decades after leaving him behind in South Korea. Part of me wanted to see the Skype calls, childhood memories, and inside jokes they shared as signs that anyone could relive a past they yearn for. Somehow I knew this possibility was unlikely. Nora had changed, and so had the place and person from her memories. Their eventual reunion in New York ends with Nora and Hae Sung parting again without consummating their relationship, accepting that the past life with each other they relished was an unreliable indicator of their present. As their story ended, I was let down, wondering what nostalgia leaves for us if not the possibility of satiating it.

I believed that nostalgia is rooted only in our memories of the past. I was wrong. Sometimes we can be nostalgic for things that never happened.

Nostalgia could be more connected to our imaginations than we think. Research from the aughts showed the areas of the brain required for memory recollection are also required for engaging in imagination. De Brigard says these findings could support a growing body of research that suggests nostalgia is motivating and tied to increased optimism, social connection, and feelings of purpose in life. Rather than reflecting our desire to time-travel, nostalgia could help us imagine how we want to bring certain aspects of the past, real or distorted, to our present.

The idea that we can be nostalgic for things beyond the past, including the future or events that never happened, led me to confront a strange realization. My grandparents have always been at the core of my nostalgic yearnings, but since I immigrated to Canada, I struggle to recall a specific memory of us together in Hong Kong.

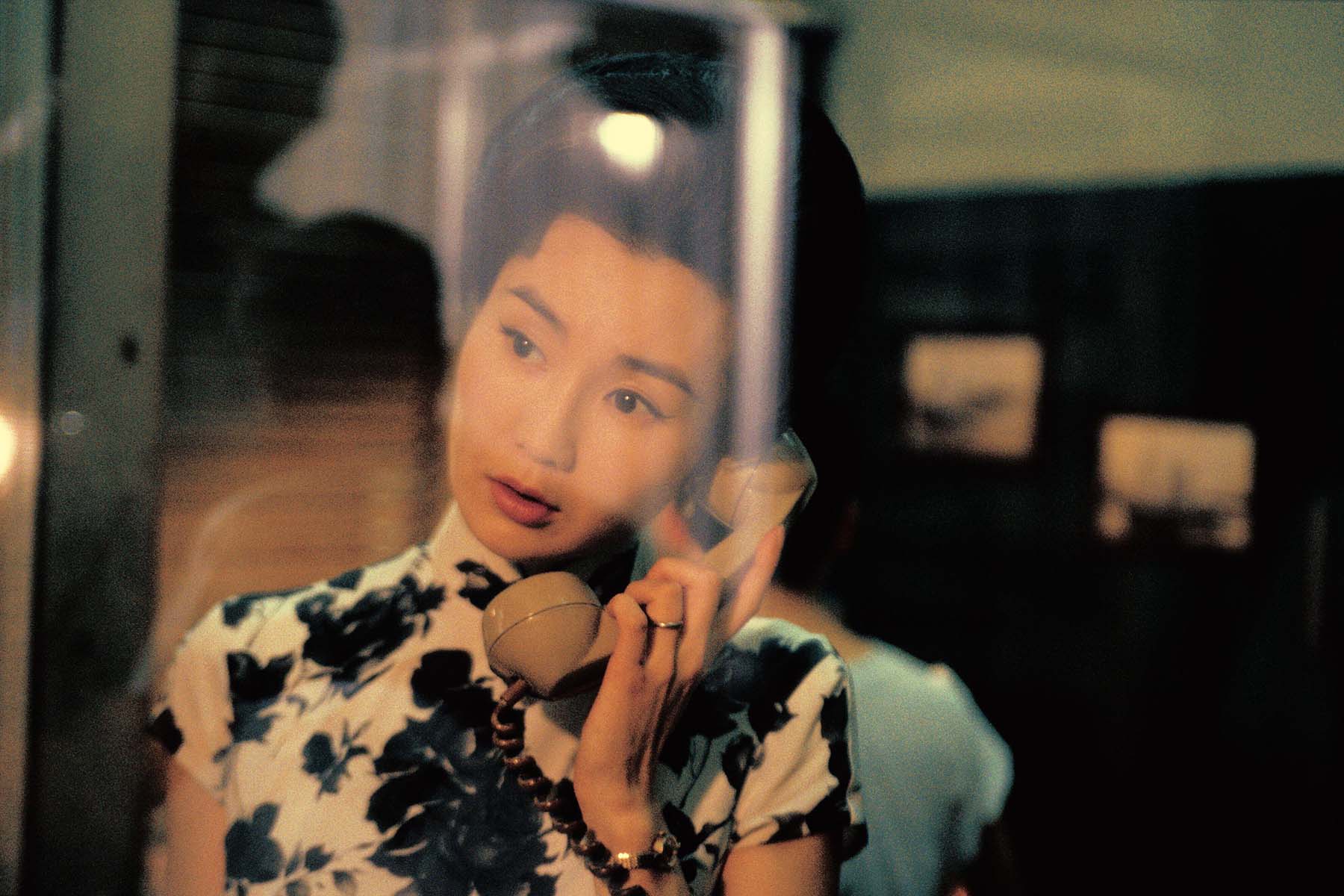

I let this revelation simmer in my mind one afternoon after rewatching one of my favourite films, director Wong Kar-wai’s 2000 masterpiece, In the Mood for Love. It’s about two neighbours who wrestle with their growing desire for one another after suspecting their partners of having affairs—only to never consummate their feelings and end up apart, just like in Past Lives. The story is set in 1960s Hong Kong, where Wong grew up after fleeing with his family from Shanghai during the dawn of the Cultural Revolution, which marked a decade-long period of political and social unrest across China. Around this time, my grandparents were in their mid-thirties, and given what little I know about them, I’ve filled the gaps by creating images of who they could have been. I imagine they were like the film’s protagonists, two people who might have worn colourful cheongsam dresses and tailored suits, restlessly moving between curbside dai pai dong noodle stands (a former fixture of Hong Kong street life, now on the verge of extinction) and crowded apartments that left no room for privacy. In imagining their past lives, it became clear that much of my regret wasn’t just for the time we lost together but was the result of never knowing who they actually were. I decided to let my yearning take the lead once more, going wherever it would take me.

Armed with strengthened skills in my native tongue, a digital recorder, and a desire to kill my nostalgia once and for all, I went back to Hong Kong in the late fall of 2023. After some convincing from a friend who uncovered his own ancestral connection to the Chinese workers who built Canada’s transcontinental railway, and prior to returning to the city, I started the process of building a deeper relationship with my own family history. During my two-week stay in Hong Kong, I spent afternoons with my grandparents, sifting through a list of questions to help them recount the people, places, and times they’ve known. I wish I could say these efforts hinged on grand plans, like putting together a family tree or book, but my intentions were rooted in something simpler. I wanted us to remember each other through something more than nostalgia.

What came out of this experience are memories that seem more concrete than the ones I had of my childhood—memories I never lived through. When they were children, my grandparents fled different cities in Guangdong, a coastal province of southeast China, to escape the Japanese invasion of China in 1931, which led to the largest Asian war of the twentieth century. They settled in Hong Kong and took on different jobs in their teenage years to support their families. My grandmother worked as a seamstress, and my grandfather rotated between working as a server at a cafe and delivering food by bike. When I asked if they had any hobbies growing up, my question was met with amusement. “What was there to enjoy?” my grandmother retorted. As I listened to them describe parts of their lives I never knew, I wondered if I’d ever have cared to find out without nostalgia.

Rather than seeing my nostalgic longings as a sign of being stuck in the past, perhaps it was time to reframe my thinking. According to Tonya Davidson, professor of sociology at Carleton University, this means approaching nostalgia with nuance, seeing it as neither good nor bad. “People are very capable of holding onto multiple times, past experiences, and future dreams at the same time,” she says, adding that the absence of longing also comes with its own losses. “If you’re never nostalgic, that’s also suggestive of a life without many rich experiences and interactions.”

I’m less troubled by nostalgia when my focus shifts away from what’s been lost and toward what my past means to me now. In reconciling the past with the present, I’ve found comfort in natsukashii, a Japanese concept that emphasizes gratitude for the past rather than a desire to return to it. Regardless of whether nostalgia is rooted in the memory or imagination of the beholder, perhaps its true value lies in its ability to reveal what’s meaningful to us in the present, whether that’s closure, excitement, or forging a deeper connection with others. At this stage in my life, it’s the latter; I can’t help but give nostalgia some credit for bringing this revelation to the surface.

My last day in Hong Kong was accompanied by a looming dread that I’d have to part from my family once again. My grandparents and I were back at the scene of our last goodbye, the door of their apartment, but this time, things felt easier. As I struggled to fight back tears and find the right words to say, I recall seeing no such need in their faces. Instead, I heard one request: “See you next year,” my grandmother said, and we agreed to never let too much time pass before we saw each other again. Rather than wishing away my nostalgia, I thanked it for this moment.

Correction, March 12, 2024: An earlier version of this article described Guangzhou as a coastal province in southeast China. In fact, Guangdong is the province; Guangzhou is its capital city. The Walrus regrets the error.