The warning, when there is one, often comes in writing: a note slipped under the door, or sent to your cellphone, or scrawled on the wall in black paint. Other times, the delivery is personal: a man intercepts your daily walk to the farm, or five of them burst into your living room. They might come during supper or just before dawn; they might wear street clothes, camouflage, uniforms, or masks. Whatever the method, the message is always the same: leave now, or we’ll kill you.

More than two million Colombians, mostly farmers, have received this message over the past eight years, pushing the number of internally displaced citizens in the country to as high as five million. Only Sudan has more. The forced marches playing out across the countryside lend a uniquely Colombian irony to the ministry of tourism’s new slogan: “The only risk is wanting to stay.” With Colombia’s decades-old civil conflict finally winding down, the ministry can point to statistics showing car bombs, kidnappings, and murders at their lowest ebb in a generation, but the trends haven’t trickled down to the country’s catastrophic accumulation of desplazados (displaced people).

A recent survey by Colombia’s constitutional court found that 37 percent of the displaced blamed paramilitaries for their situation, the most often-cited cause. These private militias began appearing in the 1980s, raised by wealthy landowners to protect their holdings. At first, the government collaborated with the soldiers, as a way of buttressing its overextended army. This allowed the militias to grow in strength and organization, though, and by the 1990s they were taking over the drug and extortion trades. They were also clearing campesinos off their land, opening enormous territories to development for their own benefit and that of a central government hungry for foreign investment.

In 2006, the “parapolı´tica” scandal broke, exposing the extent to which former president Álvaro Uribe’s government was colluding with the militias. One-third of Colombia’s politicians, including several members of Uribe’s inner circle, have since been indicted or investigated for links to the groups. Uribe himself slipped the noose, accepting a post at Georgetown University in Washington, DC, when his second term ended last summer. Meanwhile, the paramilitaries’ work goes on.

Lay a map of the country’s natural resources over one of its abandoned farms, and their motives become clear. As one expert was quoted as saying in a foreign government report, “Colombian regions that are rich in minerals and oil… are the source of 87 percent of forced displacements, 82 percent of violations of human rights and international humanitarian law, and 83 percent of assassinations of trade union leaders in the country.”

The government in question was Canada’s, the report delivered by the standing committee on international trade. It landed in 2008, just as debate over the Canada-Colombia Free Trade Agreement (CCFTA) was heating up. Like other investigations before and since, it made clear that many of the opportunities for foreign investment in Colombia were being underwritten by government-abetted atrocities. “Given the violent way commerce is undertaken, profit is extracted, and exports are generated,” our parliamentarians heard, “Canadian investment in trade would be complicit in that violence.”

Paramilitary violence in Colombia has opened an area larger than Costa Rica to investment; much of this newly productive land lies in Antioquia, the industrial heartland in the northwestern Andes, renowned for its perfect weather and the fierce business instincts of its inhabitants. With its gold-stuffed mountains and a subtropical climate ideal for coca and African palm, Antioquia generates 15 percent of the country’s GDP, and roughly the same proportion of its desplazados. They come without pause to the department’s capital, Medellin, day after week after year: 8,900 in 2004; 17,000 in 2006; 27,000 in 2009; and over 30,000 in 2010.

Part of Medellin’s magic is how it has managed to absorb more than 200,000 traumatized paupers—one-tenth of its population—without anyone really noticing. “You can walk today in Medellin’s downtown, and it’s full of people,” beamed Liberal MP Mario Silva after a visit in 2008. “[That] wasn’t the case ten years ago.” Indeed, his trip came at the end of a two-decade decline in homicide rates, which transformed Medellin from the most dangerous city on earth in the early 1990s (when the reign of the drug lord Pablo Escobar saw some 6,000 murders a year) to the “city of eternal spring” one sees today: a modern metropolis of skyscrapers towering over leafy boulevards plied by fleets of shining, reliable taxis. Small wonder Colombian officials felt confident bringing Silva and other parliamentarians here. But the trip’s itinerary shielded the Canadian visitors from the seething comunas that surround Medellin’s prosperous valley floor. There, too, is Medellin. It is the Medellin of the desplazados, those legions driven from the countryside at gunpoint, only to find their troubles have just begun.

Iarrived in the city on a lukewarm night at the end of June, soon after the Canada-Colombia Free Trade Agreement had passed through Parliament. Life magazine described Medellin as Colombia’s “capitalist paradise” back in 1947, and the tag still holds even though the factories of a half century ago have been replaced by banks and shopping malls. The city’s water, electricity, and transit systems are all profitable, and its medical industry draws elites from around the world for procedures from breast implants to heart surgery. During my three-month stay, I beheld fashion shows and flower festivals, a metro that runs with Nordic precision, the inevitable salsa clubs, and an international poetry slam that drew thousands beneath a driving equatorial rain. Escobar’s Medellin had been reduced to $10 tours of his former haunts and his grave.

And yet it was but a ten-minute walk from my lightly guarded apartment complex in the San Diego district to the Exposiciones metro station, and from there another ten-minute ride over the city’s rooftops to Comuna 13, one of the most lethal neighbourhoods in Latin America. Twenty minutes from San Diego to Comuna 13. It was a frequent topic of conversation, even among paisas (as Antioquians call themselves), how the city was two in one—turn a corner, and you could confront another reality.

The first people to take me to Comuna 13 were Carlos Mario Muñoz and his wife, Luz Marie Duarte, both desplazados and former residents. They were fourteen and eight, respectively, when their families were forced to move to the city. After they met and married, they found their own flat in Comuna 13, eventually moving three more times because violence had engulfed their lives. On the second occasion, an army raid in 2002, soldiers mistook Carlos for a rebel and struck him behind his left ear with a rifle butt, permanently damaging his hearing. The first thing I learned about him was to walk on his right side.

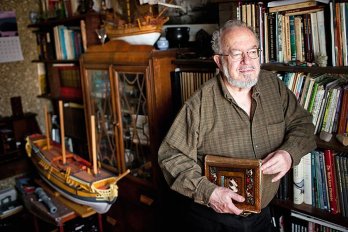

In 1998, he was elected as an unofficial representative of Medellin’s desplazados, and he has won re-election every four years since. He had an inexhaustible supply of stories, which he deployed in dense, rapid Spanish, illustrated with pantomime. Over the course of a conversation, his eternally stubbled face would contort with Shakespearean emotion while Luz Marie, a sweet indígena from the Caribbean coast, rolled her eyes and slapped his arm whenever he went too far.

We met on the cement platform of the Santo Domingo station downtown. I was surprised to see they’d brought four of their five children with them; the eldest of the pack, Yasira, was five. The kids played around our legs as we boarded the train, showing none of the nervousness I felt about entering what several people had described to me as a war zone. When we disembarked at Comuna 13, Luz Marie handed me her baby. I carried the infant up a maze of uneven concrete stairs, narrow alleys, and kiosks, past mothers combing their daughters’ hair and viejos playing dominoes.

Finally, we reached the house where the remnants of Luz Marie’s family still lived—her mother, one brother, an indistinguishable gaggle of cousins and aunts, and her grandpa. Her father had been the brood’s first casualty, shot and killed in 1993 by paramilitaries that had ordered him to leave his farm in Apartadó, nine hours to the north. A few months after that, the same men shot her mother in the stomach; she survived, but the family fled to Medellin, settling in the house where we now stood. It was one of an endless succession of identical shacks woven into the steep hillside like swallows’ nests—its cinder-block exterior, its chipped cement patio festooned with clothesline. As in all the rest, portraits of Jesus and Mary and family members living and dead adorned the drab walls inside.

Luz Marie’s mother was a quiet woman with scarred cheeks. When I asked her if she hoped to return home one day, she scowled and shook her head. “At least [here] there’s a hospital close by,” she said. The family had visited their old farm two years earlier and found a small forest of African palm where yucca, banana, maize, and other crops had once grown. Their house was still there, but the woman who answered the door threatened to call her brothers if they didn’t leave. They did, and never went back.

In 2004, one of Luz Marie’s brothers—a soldier, twenty-two years old at the time—answered a knock at the door while she was in the bedroom. “I heard the shot, and he was dead by the time I came out,” she said. “I found him lying where you’re standing now.” Whoever had pulled the trigger disappeared, never to be seen again. Medellin’s outlying neighbourhoods were made for disappearing; seeing their oceanic warren of interconnected homes and bifurcating paths up close, you understand how Escobar eluded capture for so long. He was sprinting across a rooftop not far from where I stood when the bullets finally caught him.

While I peered about, Luz Marie’s last surviving brother, James Richard, sat against a wall, watching me with crossed eyes. He, too, had been shot in the head—five years ago, at the age of fourteen. Though his eyesight was now scrambled, he still carried packages for the same gangs he’d been running with when he was wounded. He was clearly, anxiously high, this and every other time I saw him. I asked if going out made him nervous, but it must have come across as a taunt. “I go where I want,” he said, then stormed into the kitchen. Months later, when I was back in Canada, Luz Marie wrote me that he had been killed.

Carlos took me outside and showed me some bullet holes in the concrete. Two weeks earlier, he said, the house had been engulfed in a shootout; Luz Marie’s grandmother had had a heart attack and died in the midst of it. The family’s women, who spoke of violent death as though offering you sugar for your coffee, still couldn’t talk about this one.

The violence that afflicts Colombia’s displaced is senseless on many fronts. Paramilitaries, coke dealers, soldiers, and teenage delinquents often sell weapons to one another between firefights, for example; they also exchange roles and trade sides with bewildering frequency. But at every level, an underlying order exists. Standing on the bullet-scarred porch, with its magnificent view of the barrio, Carlos laid it out for me. “That soccer pitch over there,” he said, pointing, “is the closest plaza—the place you go for the vice. City council must have built a hundred pitches in the past ten years, and they’ve all ended up the same.” He began an impression of a man unhinged, swaggering around the patio with an imaginary pistol and a distorted leer, then composed himself and carved a finger through the air to demarcate the slum’s fronteras invisibles. “Every neighbourhood in the barrio has at least one plaza, every plaza has its own gang, and every gang is working for one of two people: Sebastian or Valenciano.”

Medellin remains a major centre for the global cocaine trade. Following Escobar’s death in 1993, the city’s underground passed into the hands of a paramilitary leader known as Don Berna. His monopoly on crime led to the first genuine ceasefire in the city, and by 2005 its annual homicide rate had dropped below 1,000 for the first time in more than twenty years. Berna was extradited to the United States in 2008, provoking a war of succession that was down to two contenders by the time I showed up. Sebastian and Valenciano kept to the shadows—the government had placed million-dollar bounties on each of their heads—but everyone knew who employed the city’s hundred-odd gangs and 3,500 child gangster-soldiers. The recruits were drawn largely from the ranks of the displaced—teenage boys like James Richard and Carlos’s own little brother, Sergio.

Carlos raised his arm and pointed to a crease in the mountainside above, near the topmost point of the tenements. Just beyond was a new highway to the Caribbean coast, now a major route for commercial trucks hauling freight from Colombia’s interior to the port city of Barranquilla. The drivers often added a few illicit kilos to their loads as they passed through Medellin.

“That,” he said, “is what everyone’s fighting for.”

Why did the Canadian government want to sign a free trade deal with Colombia? With half its population living under the poverty line, the country hardly qualifies as a burgeoning untapped market. Most of the products moving between the two countries were already tariff-free prior to the deal, and the money this trade generated added up to less than 0.1 percent of our GDP. Examine the FTA Canada signed with Chile in 1996, and you see that it changed nothing, really. Our exports to that country grew by all of 6 percent over the next decade, while trade in services actually decreased. As for our largest Latin American free trade partner, Mexico, the most obvious outcomes of NAFTA, signed in 1993, have been the flight of millions of farmers from Mexico’s corn-growing states, and a flood of immigration northward.

Canada’s impact on Mexico, meanwhile, has been minimal, overshadowed by that of NAFTA’s third signatory. But there is one area, particularly relevant to the Colombian case, where Canada’s weight rivals that of the United States: the extractive sector. Some 60 percent of the world’s mining companies are listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange, and Calgary-based oil and gas corporations are ubiquitous in South America. The extraction companies listed on the TSX add over $50 billion a year to our GDP, and have helped Canada become Latin America’s third-largest source of foreign investment. Canadian mining imports from Colombia more than doubled between 2004 and 2009; by 2008, more than half of the mining companies operating there were Canadian. Seen in this light, the CCFTA suddenly makes sense.

According to a report by the Canadian Council for International Co-operation, an umbrella group of development NGOs, the trade pact, which is now in force, “provides, arguably, the most effective enforcement regime ever incorporated into trade agreements because it can be invoked to win damages by countless third party private investors.” In other words, once a Canadian company buys into a project in Colombia it is legally insured against, say, a change in the tax code or an indigenous uprising. However, the FTA’s attendant silence regarding investor conduct raises some awkward questions in a country with little capacity to enforce human rights or environmental safeguards.

In the early 2000s, the Canadian International Development Agency, and the Canadian Energy Research Institute, a pro-industry think tank based in Calgary, helped Colombian policymakers amend the country’s mining regulations. The ensuing reforms loosened environmental protection measures, diminished worker rights, and reduced the royalties paid by foreign companies for access to mineral deposits. Countervailing measures would have been introduced in Canada with the passage of Bill C-300, which was designed to establish oversight of Canadian resource corporations working in developing countries, but the bill was defeated last October by the Conservatives, in a vote of 140 to 134 (fourteen Liberals abstained, Michael Ignatieff among them). During the debate over the bill, Ottawa and industry representatives argued that enforcement measures were unnecessary. Canadian companies have the highest standards of corporate social responsibility in the world, they said, and bureaucratic red tape would reduce our competitive edge.

To see whether Canadian mining companies were indeed behaving responsibly in Colombia, and to better understand the connection between them and the desplazados, I decided to look into a Toronto-based gold mining junior called Medoro, which had recently acquired two major claims within a half day’s drive of Medellin. One of its new properties is in Marmato, a town of 2,000 inhabitants plastered to the side of a steep and thickly forested mountain. Álvaro Uribe’s son Jerónimo, whose business empire includes assets in a mining waste disposal company, had visited the area shortly before I began my investigation.

The mostly indigenous and Afro-Colombian residents of Marmato have been perforating their mountain by hand for 450 years—not the easiest of livelihoods, but one over which they had some control. Now Medoro was planning to relocate the entire town and convert the mountain into an open-pit mine. Before the company could proceed, though, it had to buy up several hundred private claims, a process it was twenty-one away from completing as I set out.

Juan Manuel Peláez, president of Medoro’s operations in Colombia, told me from his office in Bogotá that the company would be responsible for building the new town, and would pay up to 80 percent of residents’ moving costs, with government sources covering the rest. “They will never get anything inferior to what they had before,” he assured me. He expected Medoro to employ as many as 2,000 workers once the mine was in full swing, with $4 of every ounce (0.3 percent of the gross profit at current gold prices) set aside for a “social fund” that he described vaguely as comprising agricultural projects, jewellery workshops, and other job-friendly exercises. If all went according to plan, every last ounce of gold would be squeezed from the ground in twenty years, though Peláez hastened to point out that it might take a decade or two longer. When I asked him what Marmato’s children could expect to live off when Medoro and the mountain were gone, he replied, “We’ll have twenty years to smooth out the transition,” brushing off both our continents’ history lessons in boom town collapse with a single confident phrase.

So far, the debate over Medoro’s presence in Marmato has been heated but non-violent. The same cannot be said of Medoro’s other acquisition, Frontino, a historic lode a few hours’ drive northeast of Medellin. It lies just outside Segovia, a gold mining town not unlike the Deadwood of legend. All salsa bars and prostitutes, its town square features an enormous bronze statue of a woman being disembowelled by a miner’s pickaxe. Segovia has a long and bloody history of warfare over the lucrative extortion payments commanded by the mine.

Medoro bought the Frontino claim for $200 million in the spring of 2010—just as the free trade agreement with Canada was being finalized—over the fierce objections of the local miners’ union, which insists it is the rightful owner. The legal dispute is as tangled as any Colombian conflict, and its results are as typical. Around the time the mine was sold to Medoro, union leaders began receiving anonymous death threats on their cellphones. A few weeks later, one of them was shot five times.

“It sounded like firecrackers,” Jhon Jairo Marulanda told me when I visited him at the house in Medellin where his wife was nursing him back to health. He’d lost 25 kilograms in two months; a polite but pained smile was as close to laughter as he could manage, because his intestines were exposed beneath his bandages. I asked him who was responsible for the shooting. “I have no idea who pulled the trigger,” he said, but added that he believed it was connected with the purchase.

When I asked Peláez what he thought about the death threats and the Marulanda shooting, he condemned them and said that Medoro was “against all acts of violence.” He added that the company expected the shooting to be investigated and that union leaders would be provided with whatever protection they required in the interim.

The police investigation was going nowhere, though, and several of the union leaders soon followed Marulanda to Medellin, a few more drops in the sea of displacement.

In August, Medellin exploded. Sebastian’s and Valenciano’s foot soldiers went on a rampage that set a new one-month record for displacement within the city: 268 families fled their homes, some because the crossfire got too intense, and others because their children’s gang involvement had made them targets for criminals and the police.

Earlier in the month, Carlos and I had gone back to visit his family. As his mother fried chicken in the kitchen, I saw five teenage boys climb the stairs outside. Three were shirtless, two were carrying machetes, and one look at their faces was enough to pull me away from the window. Soon afterward, the first shot went off. It came from a rooftop not far above ours, and was quickly followed by a second, this one returned by a pair of cracks from a long way away. Then the shots started to come in staccato bursts from near and far.

Carlos’s aunt, who had been smoking in the doorway, dashed inside. Sergio, Carlos’s youngest brother, admonished us to close the door, but we were protected from stray bullets by the house two metres opposite, so no one did. A pair of soldiers ran by, holding their machine guns tight to their chests, glancing inside as they passed. After the next round of gunfire, they raced back and hurried up the stairs. “Aren’t you scared? ” Carlos’s mother asked me. I told her I felt safe behind the thick concrete walls, which was partly true; really, though, it was the general lack of concern in the room that kept me at relative ease. The gunfire sounded like firecrackers, just as Marulanda had said. I remembered something Carlos had told me once: that when his kids heard firefights in their neighbourhood, they said, “Qué pereza”—what a bore—“now we can’t go to the park.”

There came a pause, and everyone cocked their heads toward the door. Carlos took a two-by-four from where it was leaning against the wall, winked at me with a sh motion of his lips, and slapped the board down hard on the cement floor. Everyone leaped. His mother cried, “Ave Marı´a, Carlos!” and he burst out laughing. “You thought they got inside, didn’t you!”

A few weeks later, rivals of Sergio’s gang did beat down the door, in hope of finding him inside. Fortunately, he was away from the house at the time. When he returned, he and his mother packed their belongings and moved in with Carlos and Luz Marie.

As the summer wore on, Carlos continued to spend his days helping Medellin’s desplazados navigate Colombia’s bureaucratic maze. When he wasn’t roaming the comunas, visiting people at home, he was loitering near the edge of Plaza Botero, where a drab seven-storey building housed the Antioquian chapter of Acción Social, the government agency that manages the desplazado register. Outside, tattered groups mulled around, huddling over cigarettes and ultra-sweet coffee. Watching Carlos move from one circle to another, stoking their indignation and explaining how to word the legal complaints that occupied their lives, it was easy to see why some in authority wanted him to disappear. His latest death threat, delivered from the curb by two men who parked their motorbikes in front of his house, had come three months before.

Acción Social only accepts 150 to 160 claimants a day, so the line usually starts forming at four in the morning. I showed up at that hour once to see it for myself, and, sure enough, two couples sat cross-legged against the wall, sharing a blanket against the thin edge of cold in the air. The ranks swelled to more than 100 by the time the sun rose. Another time, when I didn’t show up until nine, a still-wet stain on the concrete testified to a murder that had taken place a few hours before.

In 1997, Law 387 came into force, committing the Colombian government to “creating conditions of social and economic sustainability for displaced populations within the framework of voluntary return or resettlement in other urban or rural areas.” In that it acknowledges the state’s responsibility to reverse the conditions that create displacement, Law 387 is generally recognized as enlightened. But as one lawyer told me, “Our libraries are filled with the most progressive laws in Latin America. The problem is getting them applied.” Between 1997 and 2003, Colombia’s constitutional court ruled seventeen times that the desplazados’ rights were being violated. Only a third of them were receiving the aid they’d been promised, and fewer than 1 percent had been given land to return to—a state of affairs that holds to this day.

A Kafkaesque array of government branches deals with the displaced, but Acción Social has the final say in who qualifies for state recognition and how much individuals are paid. “Out of ten people who apply, two are approved,” an official from another department told me, on condition of anonymity. “Of the remaining eight, three give up and five apply again. In the end, four out of ten are accepted—but they still haven’t received any support, so now they have to fight for their cheques.”

Someone in Acción Social eventually got wind of the foreign journalist loitering outside their office and sent forth an invitation for me to meet the executive director, Olga Londoño. A decrepit elevator transported me up three floors to a sterile antechamber, where I found myself surrounded by a knot of solemn, threadbare men and women waiting for their turn with the bureaucrats. “They killed my son,” said the first person to speak up, a slight woman whose grey hair was pulled into two severe braids. “He disappeared three years ago. I looked everywhere for him, until one day three men came to me in the street and told me to stop asking questions unless I wanted to end up like my boy.” She spoke with increasing urgency, blinking rapidly to clear the tears from her eyes. “When I kept asking around, the threats got worse: men were coming straight into my house. I moved to my sister’s house, but they followed me there. I moved eight times, but they followed me everywhere I went. Finally, I came to Medellin… ” She trailed off abruptly. Other voices rose to fill the void, but suddenly the cubicles and corner offices of Acción Social opened up, and I was ushered inside.

“The reason they line up so early,” said Londoño, once we’d sat down with our coffees, “is that we paisas have the habit of rising before the sun.” A brisk blonde in her mid-forties, with a permanent half-smile, Londoño waved off my suggestion that Acción Social was overwhelmed by the number of people clamouring for help. “What the desplazados need to realize,” she told me, “is they can’t rely on the state to solve all their problems. They say they’re getting nothing, but don’t their children go to school for free? ”

She had a point—up to a point. The children of the desplazados did indeed have their elementary school and basic health care fees waived, and many wrested a cheque from the government every three months for two or three hundred dollars. They were unlikely to starve in Medellin, which few were willing to concede. But their existence was precarious; they were largely illiterate and unskilled, and uncertain how to survive in the city. They believed the government had a duty to help them become self-sufficient, because the government had taken everything away in the first place.

“I have six sewing machines at my house,” Carlos told me later. “My wife and I could produce 500 blouses in a month.” In ten years, however, they hadn’t been able to get a start-up loan. At the same time, Medellin’s once-burgeoning textile industry was dying out, thanks to an influx of cheap Chinese wares.

By the time I left in September, the family’s one-bedroom home sheltered not only Carlos, Luz Marie, and their children, but also two grandmothers, a cousin, Luz Marie’s sister, and Sergio. Carlos’s dad would have been there as well, had he not been in the hospital. The gang rivals who had come looking for Sergio weeks earlier had cut the old man’s foot while searching the house. Because he was diabetic, the wound had become badly infected. The doctors had already amputated one of his toes, and they were waiting to see if they would have to take off the rest of his foot. (Eventually, they did.)

The last time I visited the family, Carlos greeted me at the doorway with a scowl. “Want to see a dead man? ” he asked. It was an overcast September day, and the neighbourhood children were flitting in and out of the house like minnows. As usual, I wasn’t sure if he was joking. I followed him into the bedroom with some trepidation.

Lying on Carlos’s bed was Sergio—alive, but perhaps wishing otherwise. He glanced at me through blood red eyes, his face the colour of bile, and tried to nod hello through hyperventilated breaths. He was shivering as though buried in ice. Carlos explained that Sergio had gone out with his new friends in the neighbourhood the previous night and wound up overdosing. “He did everything!” Carlos exclaimed, pantomiming a snort-smoke-guzzle combo that ended with him nearly falling over. Then he straightened out, and for the first time in months I saw him look truly defeated.

“Mira,” he said, indicating a camouflage duffel bag on the bed beside Sergio. He unzipped it and pulled out the contents: a camo jacket and trousers, black boots, a black beret, a homemade-looking pistol with uneven welds, and several bullets. While Sergio had been out on his tear, Carlos said, a paramilitary parade had wound past the house. It stopped at the soccer pitch nearby—hundreds of young men in camouflage, marching in strict military formation, polishing their point turns and salutes. After it was over, a group of them came to the house. They belonged to the Cacique Nutibara, a paramilitary group connected to the gang Sergio had fled the month before, and they’d come to re-enlist him. “Tell him it’s time to come back to work,” they told Carlos. “If he tries to hide again, you and yours will get the bill.” They left the bag behind.

Officially, the Cacique Nutibara had demobilized in 2003. They’d given Sergio a gun back then, too, paying him to pose as a member for the disarming ceremony. Four years later, they were rounding up fresh recruits for a detachment operating several hours south of Medellin. It was Sunday afternoon, and Sergio had thirty-six hours to recover. His ride was leaving Tuesday.

This appeared in the May 2011 issue.