Mass violence motivated by misogyny is repeatedly attributed to mental illness, framed as the act of a lone man driven to snap by his disordered neurology. That’s what happened in Montreal when a gunman killed fourteen women in 1989. It happened again when another man murdered six people in Isla Vista, California, in 2014. And again when a fifty-one-year-old denturist killed twenty-two people in and around Portapique, Nova Scotia, in April, in the deadliest mass shooting in Canadian history.

Listen to an audio version of this story

For more audio from The Walrus, subscribe to AMI-audio podcasts on iTunes.

The connections between mental illness and attacks like these will be explored in depth in a trial set to start this November. Alek Minassian is accused of killing ten people and attempting to kill sixteen others by driving a van through crowds of pedestrians on a Toronto sidewalk two years ago. The judge in the case has said the outcome will turn not on whether Minassian committed the crime but on his state of mind when he did.

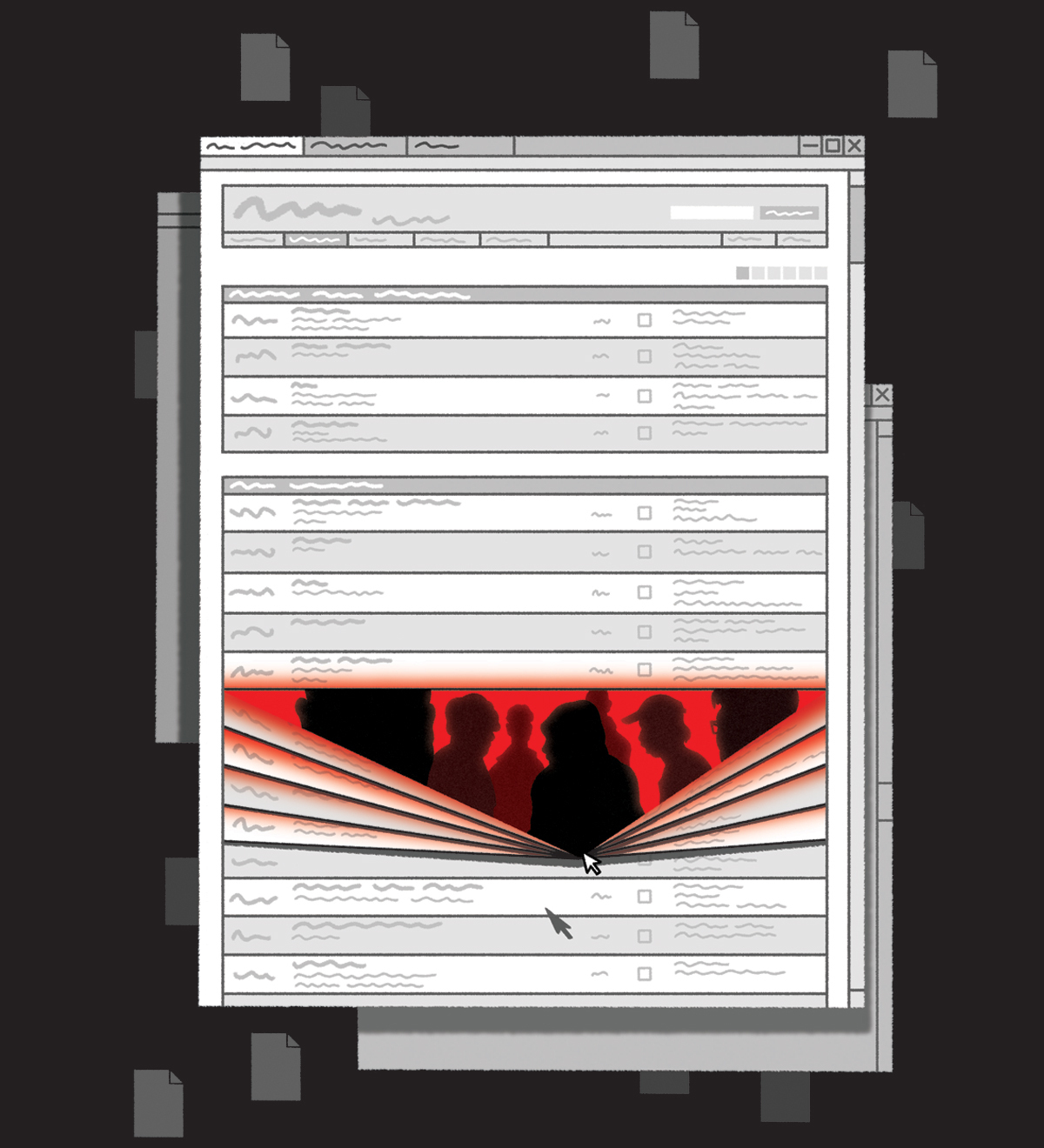

Hours after the attack, Minassian told police that he wanted revenge. He’d been rejected by a woman and was part of a group known as “incels,” a community of self-described “involuntarily celibate” men who gather online to share frustrations about a lack of access to sex. Thousands of users fill forums on websites like 4chan and other, darker parts of the internet. They discuss violent fantasies—such as ruining the good looks of attractive men and women with acid attacks—encourage rape, and advocate for mass killings. In the last few years, some of these calls have resulted in attacks offline, new developments in the tradition of misogyny-based violence that has existed for the duration of human history.

It has always been easier to isolate the perpetrators in these cases by their psychologies than to ask, How did we get here? But the research we gather after every misogyny-motivated mass killing shows us something we’d rather it didn’t. It reveals that there is a terrorist ideology at work and online forums have given it a place to fester and spread. One study, for example, published last year in the Journal of Language Aggression and Conflict and conducted by six researchers from around the globe, used language analysis to determine that the incel ideology frequently has links to violent extremism. For example, the forums’ users have a unique and well-developed subculture language that clearly defines an in-group (the people who aren’t having sex) and an out-group (the people who are). The forums also contain direct incitements to violence, and some users frame the only solution to inceldom as harming one of the out-groups. The fantasies are vivid, as is the glorification of people who have carried out those scenarios.

In May, the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (csis) moved to classify the incel movement as ideologically motivated violent extremism, which could make it easier for law enforcement to lay terrorism charges in the event that an attack is committed by a member. The day before that announcement, the rcmp laid what is likely the world’s first-ever terrorism charge against a self-identified incel, a seventeen-year-old who had killed a woman and injured two others in a Toronto massage parlour.

Still, the narrative of the unstable lone wolf endures. And, as researchers try to move past the paradigm of violence and mental illness, they’re learning more about the anger brewing in these forums. To explain how that anger has become a social issue, Amy Coren, a Florida State University (fsu) researcher who focuses on the incel community, offers an analogy. When you walk into a restaurant, she says, you either look for a hostess station or seat yourself if there is a sign that says to. You don’t walk into the kitchen and start cooking. The question is, Why not? The script that tells us what to do inside a restaurant is one of thousands that run through our heads every day, tacit knowledge about how to interact—how to be, really—in society. Somehow, she says, the incels’ scripts have been twisted. “Our questions should be, How do they get these scripts? How do they think that’s a valid way of interacting with the world?”

Pundits have long cast about for simple explanations to the tangled problems of misogyny and violence. Days after Toronto’s van attack—and before csis had linked the incel movement with terrorism—one columnist wrote, “I am sure that many people were relieved (as I was) when [the theory that this was a terrorism attack] turned out to be wrong. A terrorist attack has far grimmer political, social and security implications than a random act of violence by a homicidal loser.” Following other attacks similarly motivated by misogyny-as-ideology, some commentators have suggested that video games, prescription stimulants such as Ritalin, or psychosis were to blame. (Such arguments continue to be made even though people living with mental illness are statistically more likely to be victims of violence than perpetrators of it.) Still others have proposed sex robots as a way to stem the sexual frustration and, ultimately, the violence. But these narrow solutions are misguided and won’t solve a societal problem. Many of the incels who frequent online forums aren’t really angry because they can’t have sex. Theirs is a conversation about power: they are angry because they can’t have sex with the women they feel they deserve simply for being themselves.They reject the idea that women, whom they view as subhuman “femoids,” have the right to choose at all.

Roman poet Horace described anger as a “transient” madness. The quotation, which has been translated in slightly different ways across centuries, comes from The Epistles of Horace, first published in 20 BCE. Two thousand years later, clinical psychologist Louis Sass would write, “the madman is a protean figure in the Western imagination, yet there is a sameness to his many masks.” This perception of the violent criminal as necessarily insane has pervaded the cultural conversation across millennia. That view persists today, even as the news fills with attacks linked by ideology we see and don’t want to believe. “The conflation of mental illness and violence is a very difficult paradigm to overcome,” says James Clark, dean of fsu’s college of social work.

The college is where new research on incel radicalization is taking place, prompted by yet another tragic attack. In November 2018, a man walked into a Tallahassee yoga studio and shot five women and one man before killing himself. The army veteran had planned the attack for months and identified publicly as a member of the incel community in a series of YouTube videos he posted under the name Scott Carnifex—Latin for “executioner.” Twice, in 2012 and 2016, he’d been charged with battery against a woman. Like many in the incel community, he’d expressed admiration for Elliot Rodger, the man who killed six people in Isla Vista, California, and left behind a garbled manifesto.

The Tallahassee man killed two women that night in the yoga studio. One of them was Maura Binkley, a twenty one-year-old fsu student. In the aftermath, her parents wanted to advocate for stricter gun regulations and red-flag laws, which would allow family members or police to petition the court to temporarily take away someone’s firearms if that person were deemed to be a danger to themselves or to others. To power their activism, Maura’s parents needed data—on intimate-partner violence, for example, and developing and recurrent misogynist ideologies—that they couldn’t find. The Binkleys decided to partner with fsu, under an umbrella organization they called the Maura’s Voice Research Fund, to support research that might prevent violence against women, including examining stalking-violence patterns, evaluating red-flag laws, and developing threat-assessment tools for people motivated to kill not a particular person but an entire subset of people. The organization’s ultimate goal, Clark says, is to produce research that can drive policy changes to help prevent future attacks.

Amy Coren, one of the researchers at the college, says her work will tie what we know about isis radicalization on websites like Facebook to linguistic and environmental analyses of incel forums. She’s working to develop a portrait of a community, she says, a typology of incels that will allow researchers and policy makers to differentiate between a “shy incel” and an “aggressive” one. The distinction might help the team identify ways to prevent violent attacks. Researchers in the field know that infighting is rampant, for example, and that there’s a visible contingent that objects to violence. “There are certainly incels who have a lot of unexpressed anger and aggression toward women, but there are a lot of incels who absolutely do not,” Coren says. “There’s a contingent that says, I feel alienated, I don’t feel like I can talk to people. They’re the ‘shy incels.’” The faction that incites violence is smaller but has an increasingly vocal bent and developed ideology, each fantasy ratcheted up to best the last.

But, Coren says, the research team doesn’t believe either of these classifications has anything to do with mental illness. “The idea that you can relate those two things seems very enticing. But it’s just a correlation, not causation. You could have mental illness and be an incel, but mental illness doesn’t cause you to be an incel. This is a sociological phenomenon that’s driven by social awkwardness, expectations, community, self-perceived deficiencies, and alienation. Those, coupled with a community that stokes the fire, are what drives the incel movement.”

The impact of social alienation is undeniable. Talk on the forums often devolves into self-loathing and suicidality. One subgroup of the incel movement, known as “blackpillers,” occasionally promotes rape and suicide for incels who are deemed too ugly to get laid. “There really is nothing else worth living for, people laugh at us for that but it’s the truth,” reads one post on incels.co. “The only reason we exist is to share love and have sex. If you can’t do that, there is no ‘hobby’ or ‘career’ that can make up or replace that. There’s just nothing.” Another reads, “An incel’s options are cope or rope.”

Inceldom, for a long time, has been viewed as a disease, not a state,” says Lauren Callahan, an independent researcher who works with Clark. This idea suggests that members are sick with the same ailment their compatriots have and that, rather than a passing state, it’s an illness that can’t easily be cured. Like many echo chambers, it keeps participants participating, stuck in an increasingly nihilistic headspace. This perspective dovetails with the idea, from terrorism theorists, that the foundational components of radicalization are needs narratives, and networks. The Three Pillars of Radicalization, a 2019 book on the subject, explains that, when someone has all three—a desire for personal significance, a narrative that guides them in that quest for renown, and a network that offers veneration to the members who validate and implement the collective narrative—they’re much more likely to progress into violent extremism. And research is proving that these online communities act as pressure cookers, speeding up the radicalization process.

Callahan has observed an increasingly militarized language style in forums hosted on various websites and on Discord servers, where private chats take place. Similar to other avenues of online radicalization, incels.co offers a posting structure that incentivizes participation and escalation. At zero posts, you’re a “recruit.” After 500, you’re moved up to an “officer” ranking. At 1,500, you’re a “captain”; at 5,000, you’re an “overlord”; at 25,000, you’re “transcendental”; and, once you reach 30,000 posts, you’re “enlightened.” If the implications weren’t so sinister, it would sound cartoonish. Coren and Callahan have also been exploring the forums’ coded messages, word usage, and preliminary links that tie excessive first-person pronoun use—talking about yourself more than about others—into the language of radicalization and extremism.

Some servers, in an attempt to rid themselves of incel communities, have treated them like rodents in a game of whack-a mole, a well-intentioned approach that has largely proven futile. In November 2017, when the online platform Reddit shut down an incel forum it hosted, the group had approximately 40,000 members. Their grievances continue to reverberate through the internet, on sites such as incels.co (more than 10,000 members) and looksmax.me (more than 6,000 members), among others. For years, incels have written posts in ciphers to evade detection by law enforcement, something the Toronto van killer Alek Minassian explained in his April 2018 interview with senior detective Rob Thomas. On these forums, map, for example, stands for “minor-attracted person” and is used to describe those who post about underage girls. “Going ER” is used as a signal for violence and incorporates the initials of Elliot Rodger, who carried out such an attack. In his interview, Minassian also told police that he’d been in private communication with Rodger and with another man, who killed nine people at Oregon’s Umpqua Community College in 2015.

Making sense of a movement in which participants are migrating to darker parts of the internet to avoid being watched can feel overwhelming. “Sometimes I think, This must be what it was like to live through the Gutenberg era,” Clark says. “I feel like an illiterate parent whose children have the Bible for the first time. The impacts of social media are just as profound.” He’s been tasked with developing a threat-assessment tool that will eventually help law enforcement and policy makers better implement redflag laws. “The real intellectual problem here is, Can we accurately predict violence before it happens?” Clark muses. “The answer is no.”

At least, not yet. In May, the Canadian government announced a ban on 1,500 types of assault-style weapons. In the same announcement, public-safety minister Bill Blair said the government plans to table gun-control reforms when Parliament is able to resume regular sessions, including expanding red-flag laws that would allow relatives, victims, and community members to report someone who could pose a threat. And, as more and more American states implement redflag laws, groups like Maura’s Voice are mining the work of security experts and forensic psychologists on related topics, such as how to protect celebrities from stalkers and assailants.

Developing a threat-assessment framework, Clark says, will include monitoring what’s happening in online forums and treating them as their own environments, with similar social and psychological consequences to the ones that arise from places people gather in person. “Most mental health professionals, including in law enforcement, are trained to work with people who are acutely suicidal or homicidal. But not somebody like the people we’re talking about, who are very angry and have an ideology of hate and may have some plans for how they want to make that known in the world,” Clark says. “There are so many different pathways to an act of violence. We’re not claiming to develop any kind of magic instrument to predict future violence. The idea is prevention.”