They were an unlikely pair, the young Nova Scotia bookkeeper and the wealthy, middle-aged American. Thomas Raddall had just turned twenty, but he had already spent several years at sea as a wireless operator on merchant ships and on remote Sable Island. His new friend Lou Keyte was an ingratiating chap with a penchant for tailored suits, a roving eye, and money to burn. No one in Liverpool—a town southwest of Halifax—was quite sure where he was from or how he had made his fortune. No one really cared.

They met in the spring of 1924 at a dance in the town hall’s assembly room, a tin-ceilinged cavern framed in dark woodwork. It was a favoured venue for community events and, on this night, a local band of tuxedo-clad young men who called themselves the Bambalinas—a name borrowed from a popular style of the foxtrot—was performing.

Raddall spotted him from across the room. Keyte, decked out in a white vest and matching spats, was a hard man to miss, even without the bowler hat he wore around town. “He was an odd sight,” Raddall recalled, “obviously a city type.” A thick, well-groomed beard made him stand out as well; to Raddall, it looked like the kind sported by officers of the Royal Navy.

Keyte was “well spoken and affable in a suave sort of way,” Raddall noted after they had a chance to chat. He mentioned in passing that he had made “a good deal of money in land speculation” in the United States. Then, as if to prove it, he sent out to a restaurant for sandwiches, sweets, and coffee for everyone at the dance. “This,” Raddall wryly observed, “made him popular at once.” Keyte was an excellent dancer and chose “the prettiest girls in the room” as his partners. Word spread that the dapper, generous newcomer was a millionaire who had bought a secluded hunting lodge north of Liverpool as his summer home.

Keyte was “a jolly good fellow” and Raddall discovered they had a lot in common. Raddall, short and stocky with deep-set brown eyes capped by dark eyebrows, was worldly for his age—his father had been killed in the Great War and he had left school at fifteen to help support his family. Like Keyte, he was a newcomer to Liverpool, an outport where ferrying liquor to thirsty, Prohibition-deprived Americans had become a major industry. And both men loved books. Keyte was well read, collected rare titles, and claimed he had made enough money to retire from the business world and indulge his passion for literature. They even agreed on a favourite author: Joseph Conrad. “There, by God,” Raddall said, “was a man who knew sailors and the sea.”

Raddall had literary ambitions of his own. He had already published a short story and dreamed of the day he could quit his day job and write full-time. He would become one of Canada’s most prolific and acclaimed authors, a three-time winner of the Governor General’s Literary Award. He produced twenty-five historical novels and works of non-fiction in his lifetime, drawing on Nova Scotia’s rich history of seafaring, piracy, and war.

As for his new American friend, Lou Keyte: he would soon be exposed as one of the most brazen and successful American swindlers of the twentieth century.

Keyte’s real name was Leo Koretz and he had struck it rich as a stock promoter. A newsman once hailed him as “an outstanding example of the Horatio Alger type of self-made young man,” proof the American Dream was within anyone’s grasp. In 1887, when he was eight, his German-Jewish family had arrived in Chicago from Rokycany, in present-day Czech Republic, to seek a better life in America’s second-largest city. Koretz, eager to get ahead as a young man, took night classes to earn a law degree while clerking at one of the city’s leading law firms. He set up his own practice in 1905—but drafting documents and wills, he discovered, was not a fast track to wealth. Desperate for cash, he drew up a fake mortgage, sold it to a client as an investment and pocketed the proceeds. When he needed more money, he forged more mortgages. Soon, he later admitted, he was churning out and selling worthless paper “like streetcar transfers.”

By 1911 Koretz was promoting a new, more ambitious get-rich-quick scheme: the Bayano River Syndicate, which purportedly controlled five million acres of timberland in a remote region of Panama that produced mahogany and other exotic woods. Hundreds of investors signed on, including Koretz’s family and his network of friends in Chicago’s Jewish community. It was a giant Ponzi scheme, with the money flowing in from new investors diverted to pay profits to established investors; Koretz skimmed off the rest to support a millionaire’s lifestyle of a suburban mansion, two Rolls Royce limousines, and expensive hotel suites. He entertained lavishly and hobnobbed with Chicago’s elite; his wife never suspected he had a mistress stashed in a South Side apartment.

His scam went viral in 1921, when he announced he had struck oil on the property and began offering annual returns of an astounding 60 percent. Standard Oil, the world’s largest petroleum company, he claimed, was offering $25 million—more than $300 million in today’s terms—for a modest stake in Bayano. Investors clamoured for a piece of the action. They camped outside his posh Evanston home and begged Koretz to sell them shares. “It was like a hot tip on a horse race,” noted one investor. “Everybody jumped on who could.”

Koretz was one of the slickest and most successful swindlers in history, a Bernie Madoff of the 1920s who kept his Ponzi scheme afloat for almost twenty years. Those lucky enough to have a stake in his burgeoning oil empire trusted him implicitly. “His followers were devout,” explained long-time friend Charles Cohn. “Everybody had confidence in him,” another investor chimed in, “and never worried about the details.” Not even the exposure in 1920 of swindler Charles Ponzi—the man who gave the rob-Peter-to-pay-Paul scam its name—could shake confidence in Koretz; grateful investors began to refer to their financial hero, in jest, as “Our Ponzi.”

The house of cards collapsed in December 1923 when a group of investors boarded a steamer for a voyage south to Panama to inspect Bayano’s vast oil fields and production facilities. Koretz saw them off, gathered up as much cash as he could, and fled. By the time word reached Chicago that they had found nothing and newspaper headlines confirmed that the Bayano windfall was a scam, he had disappeared. One official estimate pegged victims’ losses at up to $400 million in today’s dollars.

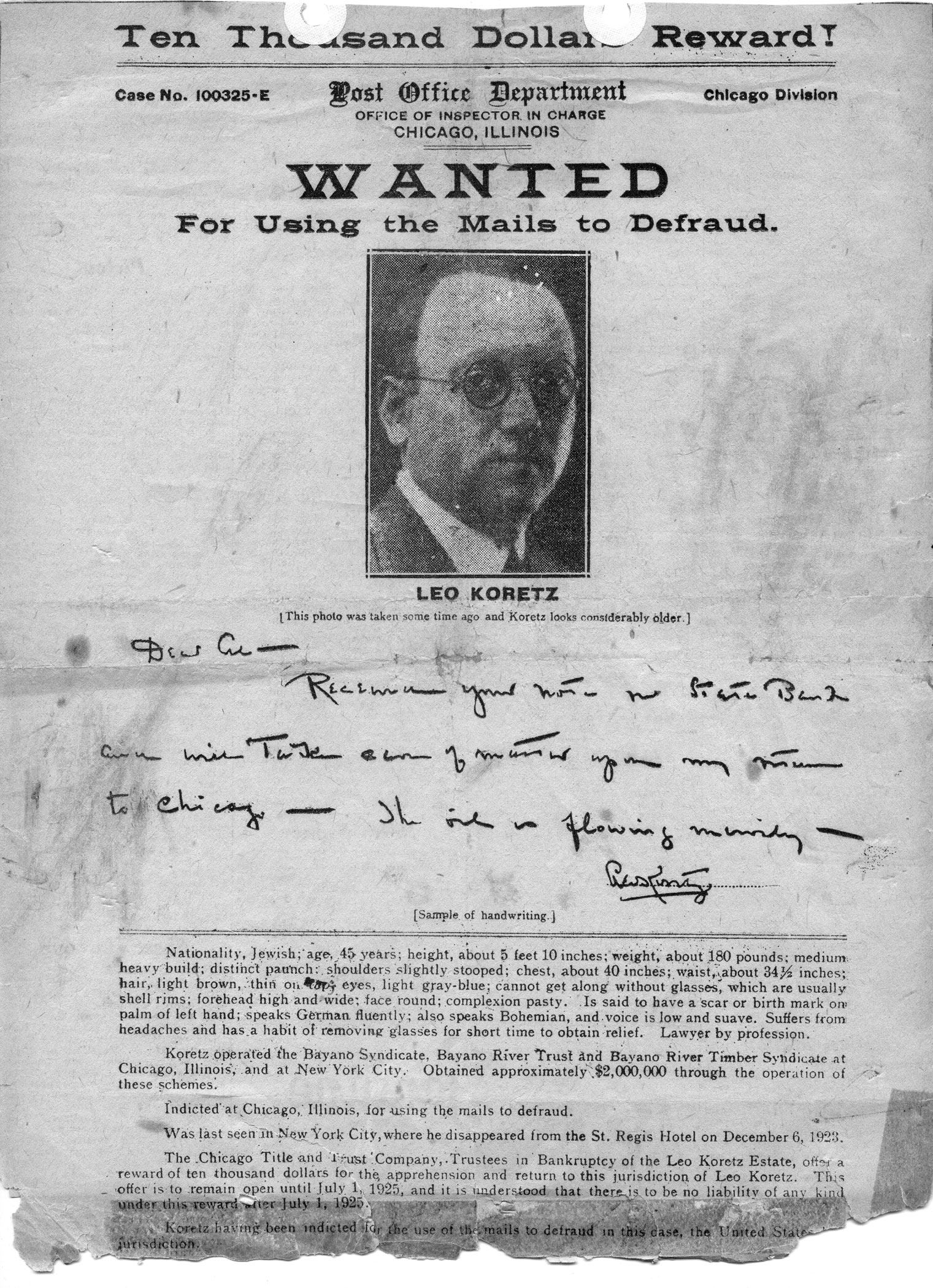

Leo Koretz spent that winter in New York City, growing a beard as a disguise and developing a new persona as Lou Keyte, retired businessman-turned-literary critic. He even bought a bookstore in the Upper East Side to bolster his credentials. But with his photo staring out from wanted posters and an international manhunt underway, Chicago was too close for comfort. When he learned of a hunting lodge called Pinehurst for sale on a secluded lake north of Liverpool—near the village of Caledonia and present-day Kejimkujik National Park—he was sure he had found the perfect refuge. When he arrived in Nova Scotia in the spring of 1924, one of the first people he met was Thomas Raddall.

Keyte immediately injected Jazz Age glamour into Raddall’s stifling, small-town world. On the long weekend in May he arranged for a fleet of taxis to ferry a dozen guests, Raddall among them, from Liverpool to a private dinner–dance at a hotel in the neighbouring town of Bridgewater. There were gifts of chocolate and cigarettes; an upstairs room was stocked with illegal booze. Leo hired the Bambalinas to perform and a menu card printed for the occasion offered diners a three-course meal and a choice of entrées: fried salmon or roasted stuffed chicken with cranberry sauce. Raddall was so impressed that he asked everyone to sign his card as a souvenir of an evening to remember.

It was just the beginning. Keyte hired contractors to transform Pinehurst into a palatial, fifteen-room country estate where he could entertain in style. It featured a music room, billiard table, outdoor tennis court, and an on-site power plant to supply heat and electricity. Money was no object for him—he was not spending his own, after all—and tales abounded of his free-spending ways. He scoured shops for antiques to furnish the lodge and drove around in a flashy Franklin, a luxury car rarely seen on Nova Scotia’s gravelled roads. He was a generous tipper who once ordered ice cream, tendered a $100 bill, and left without asking for change. With cash in short supply in Nova Scotia—the Great Depression, it is often said, started a decade early in the province—an American newcomer was doing his part to revive the local economy.

The Halifax Herald introduced Lou Keyte to its readers as “a writer of reputation” from New York; he did everything he could to play the part. Keyte was sometimes seen on Liverpool’s streets toting armloads of books. He claimed he had written several plays—none, he confessed, had made it to the stage—and articles and book reviews for American magazines. He boasted of having discovered and championed the work of Zane Grey, whose wildly popular western adventure novels had made him the bestselling author of the 1920s. It was little wonder the book-loving Raddall believed he had found a kindred spirit.

Keyte soon became a familiar figure in Halifax, where he spent many weekends at the city’s best hotel. He mingled with Nova Scotia’s elite at the prestigious Royal Nova Scotia Yacht Squadron and frequented shops, restaurants, and dance halls. When American actress Edna Preston performed in Halifax that summer, Keyte treated her eighteen-member entourage to a gala dinner and gallons of champagne. One Halifax newspaper christened him the “prince of entertainers.”

Keyte proved worthy of the title that August, when he hosted a housewarming bash at Pinehurst. Raddall’s name was among more than 100 on a guest list that included local politicians and businessmen. It was, Liverpool sportsman Laurie Mitchell recalled, “a brilliant party that astonished everyone.” Liquor flowed, couples wandered the grounds, and Keyte hired orchestra players to provide the soundtrack. Even the Halifax Herald took note of the lavish affair, filing a brief item reporting that “dancing was the chief entertainment.” It was as if Jay Gatsby, the wealthy and enigmatic title character of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s classic novel of 1920s excess, had been transported to Nova Scotia for the night.

As far as anyone in Nova Scotia knew, this charming, generous millionaire was a bachelor. Keyte was in his mid-forties and a bit overweight, with a pasty complexion and a face as round as his thick-lensed glasses, but his charm and his money made him a catch. He was rarely seen without a female admirer in tow. “Keyte had a fickle and insatiable appetite for women,” Raddall noted, and lived “at a furious pace . . . passing from one woman to another like a hummingbird in a flower bed.” He finally set his sights on Mabelle Gene Banks, the twenty-something daughter of the publisher of Caledonia’s weekly paper, the grandly titled Gold Hunter and Farmers’ Journal. Her betrothed called her Topsy. Her parents approved of the match, “flattered with the notion,” as Raddall put it, that she might marry a millionaire.

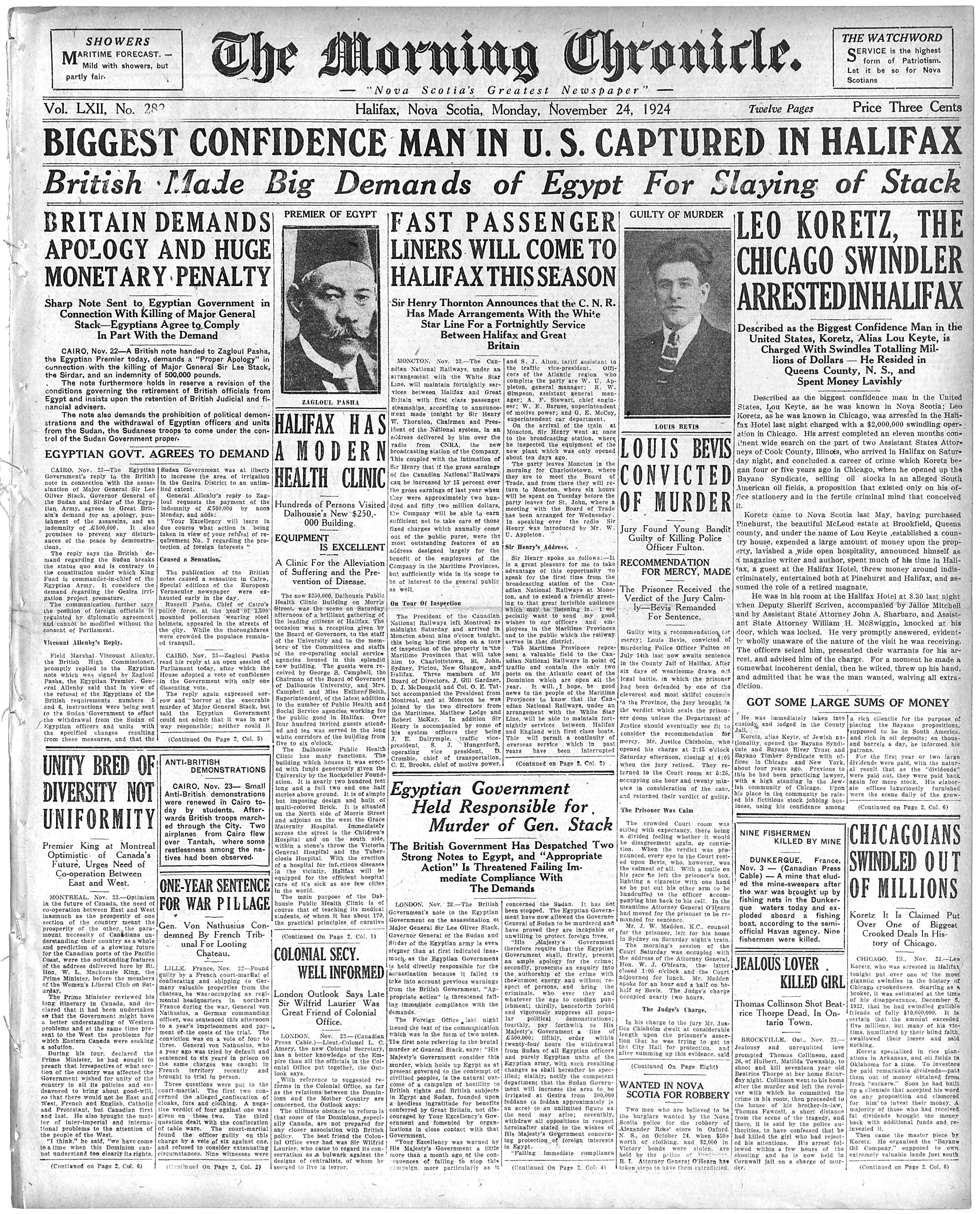

But Lou Keyte’s booze-soaked, orchestra-serenaded Nova Scotia romp came to an abrupt end in November 1924, with a knock on the door of his Halifax hotel room.

A chance discovery was his undoing. When he dropped off a suit jacket at a Halifax tailor shop for repair, a label bearing his real name was discovered in the lining. The news soon reached Chicago. Keyte was arrested and extradited to the US on charges of fraud and operating a confidence game.

In Nova Scotia, where he had fooled almost as many people as he had in Chicago, reaction ranged from bemusement to disbelief. Halifax’s Morning Chronicle scoffed at how the swindler had used his generosity and ill-gotten wealth “to flutter various sensitive hearts and silly minds.” Keyte’s final Canadian caper proved that a showman’s bravado, a dash of charm, and a display of wealth could overcome caution and common sense. Thomas Raddall was as astonished as anyone to discover his new friend was a notorious con man. He was also at a loss to understand why a fugitive from justice would draw so much attention to himself. “Had he chosen to live quietly and inconspicuously at Pinehurst he might have evaded capture for the rest of his life.”

Raddall continued to write and publish and finally quit his pulp-mill job in 1938, launching his literary career. When he published his memoir In My Time in 1976, he included a brief description of his adventures with the “jolly millionaire,” Leo Koretz. At some point Raddall wrote a more detailed account of that memorable summer, a 4,000-word story entitled “Pinehurst,” but for some reason it was never published. The manuscript was among the papers he donated to the Dalhousie University archives before his death in 1994. The same file contains the menu card “Lou Keyte” autographed during the Bridgewater dinner-dance, and a reproduction of a wanted poster, offering a $10,000 reward for Koretz’s arrest; Raddall had clipped it from a Halifax newspaper back in 1924 as another keepsake.

Keyte’s exploits were still fresh in Raddall’s mind in 1953 when he published his novel Tidefall. The protagonist is a Nova Scotia ship’s captain with a taste for fine clothes who makes a small fortune as a rum-runner in the Caribbean. Saxby Nolan double-crosses his bootlegger bosses and hides out in New York City—just as Koretz did—before returning to Nova Scotia. Nolan’s past catches up with him when one of his former associates arrives and demands money in exchange for his silence. His old friend, it turns out, is desperate for cash because he has been swindled; a slick-talking “shark” had convinced him to invest $20,000 in a bogus oil company.

The company supposedly controlled oil fields in Texas, not Panama, and the swindler is never named. But the source of Raddall’s inspiration is unmistakeable.