Afew months after my first visit to Cape Dorset, I had a dream. I was at a crowded gathering in the small Nunavut community on a brilliantly sunny day. But rather than one of the little one-storey prefab buildings scattered across the windswept rock, I was in an apartment building—a very high, somewhat rundown modernist tower with a south-facing view. The apartment was small and jammed with Inuit people, all having a good time. I was the only southern white person there, a recipient of their generosity, as I had so recently been in real life.

The view was extraordinary. Below us lay the entire topography of Hudson Bay, its familiar, lopsided udder shape inverted from its conventional southern orientation. The view was as if seen from the stratosphere, with the water stretching out like hammered silver, shining in the late-afternoon spring light. The bottom of the bay was cloaked in a blanket of clouds, and they, too, were lit up to a satin-sheened brilliance. I was bewitched by the beauty, startled by it, but around me everyone carried on carousing, oblivious. A group of young men were gathering on the balcony—too many, it seemed to me, to be supported by it. I was worried it would break, but as an outsider I was wary of offering advice.

When I awoke, my mood was ambivalent. I was moved by the radiance of what I had seen, but also anxious about the possible calamity. This, I quickly realized, had been the frame through which I had experienced Cape Dorset, a small town that has been the site of a unique intercultural experiment between the Inuit and the white worlds for more than half a century. I had been enchanted by the beauty and the culture of the place, but disturbed about what Inuit had endured, and how much they still stand to lose by adopting the structures and values of the white world. I have now made two visits there to learn about printmaking at the renowned Kinngait Studios, the jewel in the crown of northern artistic production, which celebrated its fiftieth anniversary three years ago. In particular, I wanted to meet Tim Pitsiulak, forty-five, a quiet, steady fixture in the community, one of its best hunters, and now one of its most promising artists. A nephew of the celebrated printmaker Kenojuak Ashevak, he leads a new generation of artists redefining Inuit art.

Artmaking in Cape Dorset has prehistoric roots, from nomadic Inuit who expressed their refined aesthetic sensibilities for millennia in tiny carvings, toggles, and amulets in bone and ivory—objects that connected them to the spiritual realm and to the animals they hunted—and in the striking textile appliqués with which the women adorned traditional clothing. These designs inspired adventurer James Houston to persuade the Canadian government to fund a pilot project in Cape Dorset in the 1950s, encouraging carving on a larger scale, and introducing Japanese-style printmaking to a people who were just beginning to move into fixed settlements. By 1960, Houston was moving on, the mantle of leadership was passed to Terry Ryan, and Kinngait was placed under the direction of the newly created West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative, one of many such co-ops set up across the North under the direction of Inuit leaders.

All artwork courtesy of Feheley Fine ArtsFamily of Eight, lithograph (2008).

All artwork courtesy of Feheley Fine ArtsFamily of Eight, lithograph (2008).For Inuit, the co-ops provided employment and hope, but Ottawa had its own reasons for encouraging permanent settlements. The Cold War had charged the Arctic politically, making it a buffer zone between Communism and democracy. Conscription of the nomadic Inuit into fixed communities enabled the federal government to assert the existence of an Indigenous population in the region, even if that citizenry was to be identified by tracking numbers. In the span of a few decades, the nomadic way of life was lost, and Canada’s claim on the North was secured.

Meanwhile, the country was looking to brand itself at home and abroad, and Inuit art became the iconography. Ookpiks and inukshuks were sold in airports and gift shops from coast to coast. Inuit prints graced our stamps; Kenojuak’s The Enchanted Owl, on the 1970 six-cent stamp, was embraced as a signifier of our identity as an emerging nation, with accents both primeval and modern. Inuit carvings served as the stuff of corporate ritual among Bay Street qallunaat, who swapped bulk-buy soapstone dancing bears and walruses at closing dinners.

Some of this art was outstanding: Kenojuak’s rapturous depictions of animals and supernatural beings; or Kananginak Pootoogook’s renderings of caribou and other creatures, works that vividly capture the specific characteristics of each species. Some of this art, however, was repetitive and formulaic. Still, markets expanded at home and internationally, directors of the West Baffin Co-op came and went (James Houston; Terry Ryan, whose forty-eight years of service ended in 2008; and a succession of other white managers), but the experiment has remained the same: to broker a relationship between a south enraptured by the “idea of North” (to borrow Glenn Gould’s famous phrase), and an Inuit community struggling to find its way forward and maintain its cultural identity. The resulting phenomenon is unique: with a population of 1,363, Cape Dorset may be the only community in the world where art constitutes the leading industry.

My second flight into Cape Dorset reminds me of my dream. Out the window, the dazzling February sun skims low on the horizon, illuminating the wind-sculpted snowdrifts and the low, rocky hills. I can’t help but find irony in the Globe and Mail double-page spread lying open on my lap. The story describes the cultural repatriation of a small historical carving of a golden rhino, found in a hilltop settlement on the Limpopo River in South Africa in the 1930s. The much-prized and now much-contested object reflects the glory of that thirteenth-century culture, its elegance and simplicity communicating an early civilization’s vital connection to the natural realm. In this it resembles the exquisite miniature carvings from Thule and Dorset that once drew the admiration of leading European modern artists—from the surrealists Man Ray and André Breton to sculptor Henry Moore—and which now reside without fanfare in southern Canadian museums. Sweep them all into a pillowcase and toss them in a Dumpster, and the whole legacy would be lost. As we barge into their world with drilling and mining projects, do we Canadians know what we have?

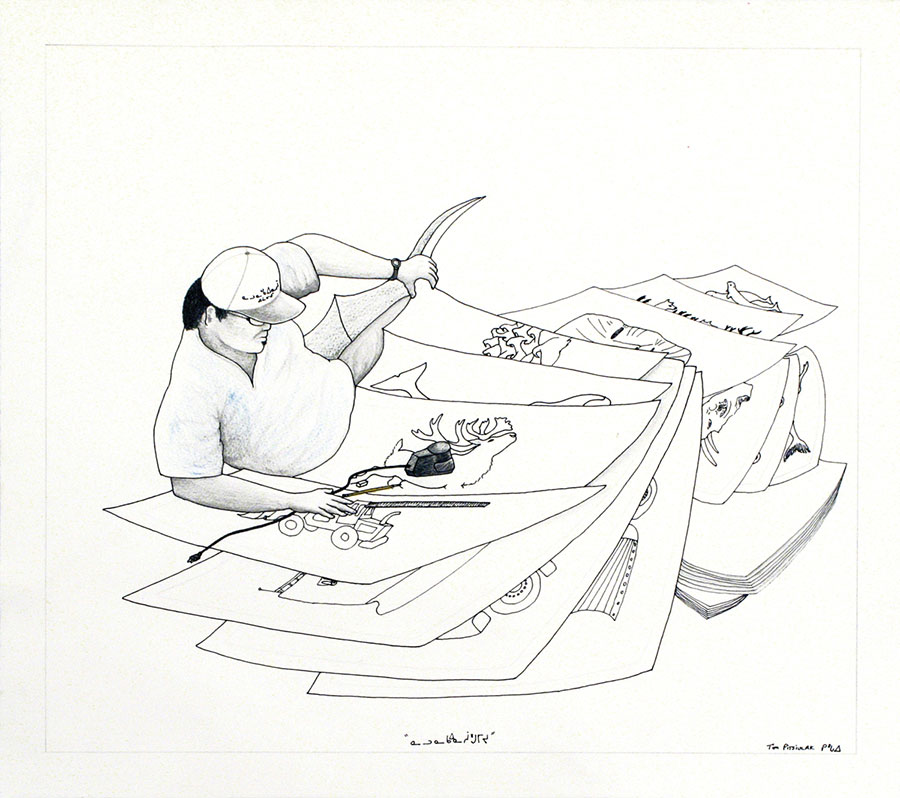

Composition (Self-Portrait with Drawings), pencil, coloured pencil, ink (2010).

Composition (Self-Portrait with Drawings), pencil, coloured pencil, ink (2010).As I circle over the landing strip, I can see the broken shapes of the melting ice at the floe edge, a mash-up of interlocking forms tinged an unearthly aqua. Small icebergs drift offshore. I am arriving a day earlier than planned, thanks to an unscheduled flight out of Iqaluit. This is the first rule of travel in the Arctic, where the only things carved in stone are the sculptures: you get there when you get there.

Stepping out onto the tarmac, I find the air dazzlingly bright and cold. Breathing in is like inhaling millions of microscopic iron filings: a harsh, metallic shock to the system. Inside the one-room airport, my welcome party is my friend Pat Feheley, a dealer in Inuit art in Toronto for thirty years, and Bill Ritchie, a white printmaker from Newfoundland who has run Kinngait Studios since 1988. In Ritchie’s mud-spattered truck, we drive over to the print shops, where we are to be accommodated in the spare but immaculately clean upstairs apartments. On my first visit, we had many cloudy days, but this time light streams in everywhere. It’s as if someone has taken the lid off the top of the world and offered you a clear shot at the universe and all of its radiant silence. The squeaking of your boots on snow suddenly sounds amped up, a kind of music you’ve never heard.

Feheley and I had done this trip together nine months earlier, she looking at work for her exhibitions in the south and talking with the artists, and I playing the fly on the wall, watching and learning. Across the road, the stonecut studio prepares the slabs, with a team of four trained Inuit printers (plus one new Inuit intern) bringing to life the multiples that will be sent south. Here, in the lithography building, another three or so Inuit are pulling proofs. But we spend most of our time in the adjacent drawing studios, where the ideas for the prints take form, and where Ritchie keeps his computer and his phone. This is where the regulars meet daily to draw: Tim Pitsiulak, Shuvinai Ashoona, Jutai Toonoo, Itee Pootoogook, and Ohotaq Mikkigak—a smaller group than in years gone by. In the background, I hear the low-budget sound of the Cape Dorset community radio station, hits from the ’60s and ’70s, contemporary pop, and gospel interspersed with local announcements in Inuktitut, a language of gently consoling, downward-crooning vowels, punctuated by consonants that chime like rattled bones, acoustic sounds produced in the back of the throat. It occurs to me that the world’s harshest place has produced its softest language.

Pitsiulak has the prime spot in the studio, right beside Ritchie’s workstation. He rises to greet me, a burly and affable presence, big-smiling and shy. We met on my first trip here, and later at a sushi restaurant in Toronto, when his solo show opened at Feheley Fine Arts, but now, even more than before, he seems disinclined to talk about himself. He is working against the clock, trying to finish a large drawing so Ritchie can pay him the money he needs for an upcoming three-week artists’ residency in Red Deer, Alberta. We talk for a bit and then, while he continues to draw, Ritchie and I sit at the computer beside him looking at hundreds of photographs Pitsiulak has taken on his hunting expeditions. The pictures reveal, as surely as his drawings, his pleasure in northern life. He often uses them as the basis for his pieces, and many have also served as source material for his fellow artists. In this traditional way, he shares his catch of images as willingly as he does his “country food” of seal, caribou, and walrus, even though the caribou herds are not as plentiful as they were when he was growing up in Kimmirut. “They would come even into the community,” he says. “When I saw caribou across the harbour, I could go and look at them—the landscape as well.” It moves him still. “If it’s a beautiful day and I’m out on the water, I will just stop the engine and float in peace.”

Butchering beluga whales on the spring ice.

Butchering beluga whales on the spring ice.Shooting is what he does well, with gun or camera, and both have brought him relative plenty. For a day in the studio, he earns $100, and then $1,000 to $3,000 for a finished work. With his wife, Mary, he has two young daughters, as well as three sons from an earlier relationship, boys he is teaching to hunt, as his father taught him. He also has a teenage daughter who was adopted by a white family in Toronto, and with whom he remains close. He frequently travels south to attend exhibitions of his work: at Feheley Fine Arts, the Toronto International Art Fair, and the Art Gallery of Ontario’s Inuit Modern exhibition and symposium last year (which he attended with Kenojuak); and for artists’ residencies like the one in Red Deer. In this community, he is a success story. “That’s the best thing about being an artist and a hunter,” he says, “the reward that comes. People [in the south] like it. What more can I ask for than that people are noticing what we have up here? ”

You would have a hard time, however, getting him to say much more. Where southern artists, like southerners in general, are conditioned to accept the assumption of artificial intimacy that comes with the interview process, Pitsiulak clearly finds it undignified and (were he less diplomatic, he would admit it) something of a nuisance. When he picks up on my curiosity about the hunt, he is quick to say that women are not included, though some, like Kenojuak’s daughter Silaqqi, are crack shots. Maybe I should talk to them. Asked what he would do if he could change one thing in his community, he objects: “I don’t want to run a place the way I want to. People have their own lifestyles.” Why would one seek to interfere? Asked if he would ever teach, he says, “When I started drawing, I never looked at anyone else. I did this all by myself, and that is what other people should do: find their own style.” The idea of judging other people, even guiding them, with that implied assumption of superiority, clearly makes him uncomfortable.

When I ask to visit his home, he succumbs to a mysterious bout of deafness. When I press the point, saying I would like to meet his family, as if by magic his wife and two small girls appear in the studio. No need for house calls when the family comes to you. I begin to understand something untranslatable between our cultures: the idea of the glorified individual—of the competition for the spotlight that drives our southern capitalist culture—has no place here. Communal endeavour has always been the only way to survive. Speaking of the self, it seems, is the ultimate gaucherie. When I look in my notebooks at day’s end, I find such entries as “We must respect our elders.” Clearly, I will need to look to Pitsiulak’s art to find the man.

During my first visit, Pitsiulak had been working on a large drawing of a narwhal, a creature he knows from his many hunting trips, although he had clipped an image from the Internet to his drawing board for anatomical guidance. As the picture took shape, he told me about his love of the Discovery Channel and nature shows from the south, and the videos made in the 1990s by Zacharias Kunuk and his partner Norman Cohn, who documented traditional hunting and survival skills from an Inuit perspective. “I saw them in my teens,” he told me. “They were shown on a projector in Kimmirut.” Now raising children of his own, he tries to restrict their viewing to nature programs.

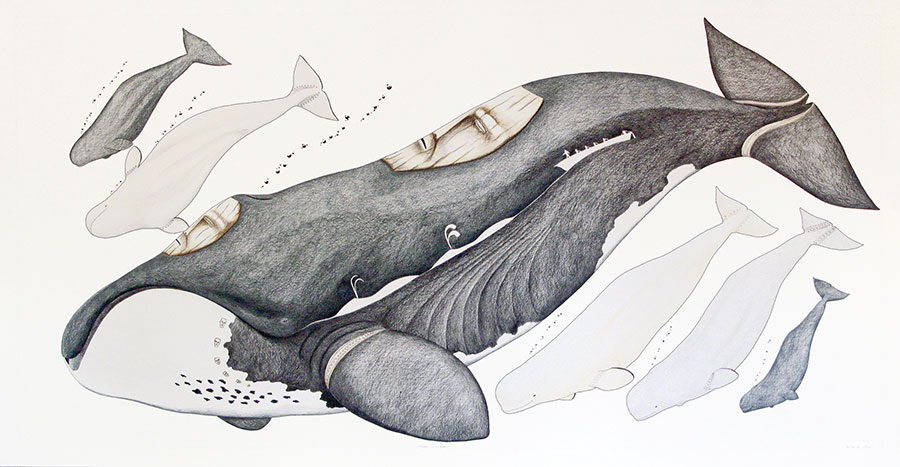

Bowhead with Beluga Whales, ink, coloured pencil (2011).

Bowhead with Beluga Whales, ink, coloured pencil (2011).In the studio, we leafed through a pile of recent drawings Ritchie had gathered for shipment south. One of the smaller ones showed an aging caribou struggling to its feet, its hooves splayed and its body torqued in an awkward position; the animal engages the viewer with its weary eye, its expression conveying the artist’s respect for the pathos of nature’s life cycles. Farther down in the pile, a drawing of a Greenland shark showed the predator as a sleek, muscular curve of flesh, its form pared of detail except for serrated teeth and a hungry eye, an image of pure, ravenous appetite. Others reflected traditional legends, like the many-tentacled Qalupalik, which he rendered with horrifying green talons; or a pair of amautik-clad whales swimming in tandem, a contemporary reimagining of the legend of Lumak, in which a mean-spirited grandmother and a blind boy are dragged out to sea by a whale.

But the major work in the pile was a two-and-a-half-metre depiction of a Caterpillar Telehandler, a piece of forklift equipment often seen around town. Rendered in flaming orange with crisply graphic detailing, it was visual dynamite, carrying the charge of the new and novel in an environment where change happens subtly from year to year. Like earlier drawings of machines (Ski-Doos, known by some in the North as snow machines, and the ubiquitous all-terrain vehicles that roar up and down the town’s main drag at night), it celebrated the trappings of modernity in this northern hamlet. Rifles, outboard engines, earthmovers, snow machines, ATVs—these things make life easier.

Afterward, he returned to a two-metre-wide drawing of a rocky hill clad in snow. Working in coloured pencil, and with complete absorption, he referred often to an eight-by-ten photo he had shot while out on the land hunting walrus. The mountain emerged as a massive, silent presence—humbling, inert. This piece of lived experience would find a swift home in the south: on a collector’s wall; in a museum (the National Gallery of Canada was an early collector of Pitsiulak’s work and owns five large drawings, one print, and more to come); or in a corporate boardroom, where executives would look at it and pine for the imagined freedoms of a life in Pitsiulak’s world.

Whites imagine Inuit, and Inuit imagine whites; Inuit art is where their fantasies meet, but the interface is changing. Kinngait continues to release its annual portfolio of about forty prints, as it has for more than fifty years. Despite stars like Kenojuak, prices for the prints have remained fairly consistent and modest, in the $500 to $2,500 range. But one-of-a-kind drawings are gaining a following and, as with the prints, the prices are regulated by Dorset Fine Arts, the co-op’s Toronto distributor, which sends the art to dealers across Canada and around the world, who then charge what the market will bear. Pitsiulak’s largest and best drawings can now sell for as much as $12,500, making him one of the most successful artists in the North. His aunt Kenojuak’s best works sell for around $16,000. Shuvinai Ashoona’s prices are close behind Pitsiulak’s and rising fast. This phenomenon of individual artists’ commanding widely differing levels of remuneration could someday lead to a break with the old co-op way of doing things, in which the revenue from higher-priced artists supports the costs of maintaining the studio and distribution, helping to fund the production of those artists who are less likely to sell. Inuit artists in Cape Dorset may hesitate to abandon a system that has afforded them predictable prices for pieces on completion (as well as studio space and material costs), irrespective of the vagaries of the southern art market.

Site of the beluga hunt, shot from another angle.

Site of the beluga hunt, shot from another angle.The content, too, is changing. Images of seal hunting and round-cheeked women smiling from beneath their parkas might have pleased gallery-goers a generation ago, but media accounts of social breakdown, gun violence, and epidemic alcoholism have undercut this view of Inuit reality. While the prints of Pudlo Pudlat from the ’70s reflected his fascination with airplanes and helicopters, harbingers of southern ways, he depicted these incursions of urban culture with evident curiosity and delight. Twenty years later, the drawings and prints of Napachie Pootoogook delivered darker scenes of family strife, sexual violence, and nightmarish hallucination.

It was Napachie’s daughter Annie Pootoogook who brought Inuit art’s gritty contemporary focus to a wider public. While Zacharias Kunuk had captured the attention of the international art world with films documenting the traditional Inuit way of life (his first feature, Atanarjuat, won the Caméra d’or Prize at Cannes in 2001), Annie’s drawings portrayed contemporary Inuit youths watching porn and television shows about hunting, families cruising the freezer section of the co-op store in search of provisions, or men beating women. (Sexual assault rates in Nunavut sit at ten times the national average.) Her crisp, candid works also depicted traumatic moments from her own troubled youth as the child of alcoholics and a victim of domestic violence. Courageously, she parted the curtain on the sorrows and sufferings of her people, at a time when post-colonial discussions had reached a fever pitch in international cultural circles.

The southern art world loved it, and Annie Pootoogook’s meteoric trajectory took her from Cape Dorset to the commercial and public galleries of Toronto and Vancouver; to the Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery in Toronto, where she held a celebrated solo exhibit in 2006; to the Sobey Art Award ceremony, where she won the $50,000 first prize that same year; and onward to the prestigious Documenta exhibition in Kassel, Germany, the ne plus ultra of international contemporary art shows. Tragically, her path also led to the streets of Ottawa, where alcoholism has left her destitute.

Shuvinai Ashoona, afflicted with severe mental illness but still highly productive, is another notable Cape Dorset artist. The white world has embraced her extraordinary depictions of transforming creatures, suicidal Aboriginal youth, psychedelic ocean dwellers, global warming, and talking polar bears—an imaginary universe that is by turns ecstatic and terrifying.

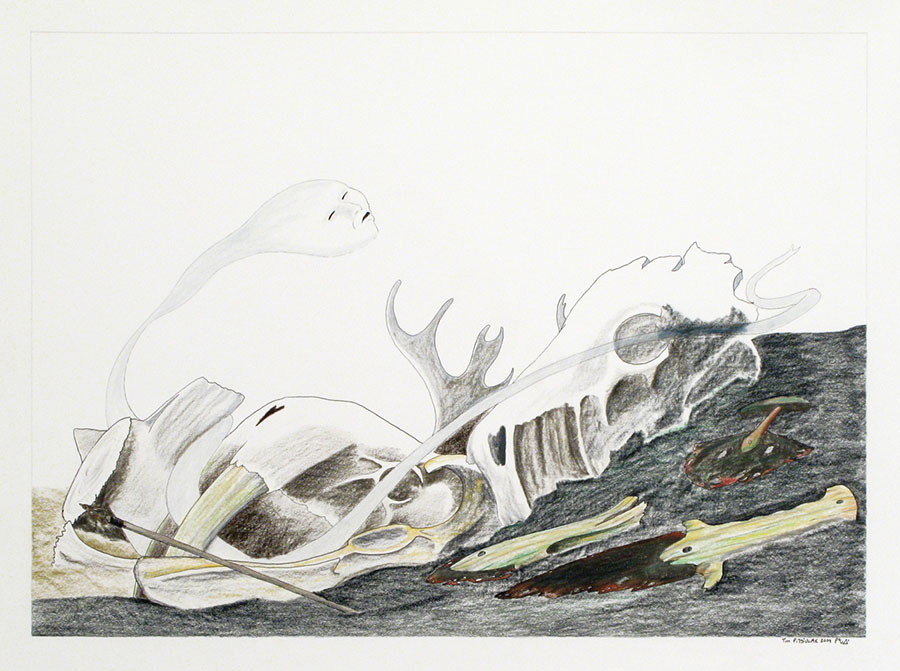

Igaqjuak, oil stick (2011).

Igaqjuak, oil stick (2011).And then there is Tim Pitsiulak. While Annie Pootoogook’s and Shuvinai Ashoona’s deep-delving work can be understood within the framework of traumatized colonialization and feminism, Pitsiulak’s art reflects another reality. It reveals his attachment to place, the rituals of the hunt, and the pleasures of providing, while representing a mode of masculinity in which he can take pride. With confidence and some defiance, he challenges the south’s guilt-ridden view of the North as a place of tragedy only.

It was always a land of extremes. In Cape Dorset, you will find a gang of listless teenagers loitering around the co-op stores every afternoon, some with eyes glazed by narcotics. Every liquor shipment yields a fresh crop of black eyes and sometimes fatalities. The town’s unique cash-for-goods art economy makes these problems more pronounced. With six deaths last year, Cape Dorset had the highest per capita suicide rate of all northern communities. Many families are still living out the legacy of the residential schools, and the trauma that resulted when tuberculosis lead to the incarceration of parents and children in southern hospitals. On one of my return flights, I saw an all-too-familiar sight: sitting in the back row with a burly trio of white policemen were two young Inuit men in handcuffs, more grist for the courts in Ottawa. When I caught the eye of one of them on my way to the washroom, he just smiled politely at me and shrugged.

Nunavut’s transition to self-government has been rocky. According to Peter Ittinuar, Canada’s first Inuit MP, who now works as a land claims negotiator for the government of Ontario, “We are at least a generation behind being the kind of society we want to be.” He says the citizens of Nunavut complain that their new leaders were unprepared. Jobs are harder to come by than they used to be, and fluency in English is increasingly a requirement for any kind of advancement.

But there is good news, too. Inuktitut is spoken in Cape Dorset by young and old alike, which Edward Sheppard, the principal of Peter Pitseolak School, says is unique in the North. And the children graduating from elementary school have better English reading skills than ever before, which should improve their prospects. Rodney MacIntyre, a new police officer, has raised money to beef up the local hockey program. Candice Waddell, the new full-time registered psychiatric nurse, is working with a childhood and youth outreach worker, Taukie Taukie, to identify and treat those in need. Waddell has instituted a mentorship program, funded by the federal government, that each year recruits eight high school students or recent graduates to work with the younger children after school, teaching them sports as well as traditional skills and games, and talking to them openly about mental health, addiction, and suicide prevention.

Composition (Bones, Ghost and Artifacts), pencil, coloured pencil, ink (2009).

Composition (Bones, Ghost and Artifacts), pencil, coloured pencil, ink (2009).There is also talk about a new heritage centre; an Iqaluit engineering firm has already been awarded a contract, estimated between $4.8 and $6 million, to build it. Funded in part by the Nunavut government, and with a commanding site overlooking the town, it would provide a new home for the printmaking and drawing studios, and a new venue for programs that now take place in the old community centre, where elders teach such skills as sewing, traditional toolmaking, and carving.

The people I meet in Cape Dorset seem to love the place. On the eve of my first visit, the Globe and Mail had published an exposé on social problems in the town, offending many local Inuit and causing them to wonder whether only tales of tragedy have traction in the south. But walk into Kenojuak’s house, and you might find her, as Pat Feheley and I did, lying on her stomach on a queen-size mattress on the living-room floor, surrounded by family, and sketching on a big piece of white paper, The King’s Speech playing on the giant flat screen TV behind her. In her kitchen was a hunk of caribou meat in a Pizza Pizza box, bloody evidence of the spontaneous resource sharing that still goes on here. At home, Kenojuak is the eye of a happy family maelstrom, as the mountain of boots and running shoes at the front door attested. Around town, she is still the queen, with Pitaloosie Saila, Kakulu Saggiaktok, Papiara Tukiki, and Ohotaq Mikkigak and his wife, Qaunaq, as vice-regents—the first generation of artists who broke the trail south. She proudly displays her Order of Canada on the wall of her living room, with pictures of her grandchildren tucked in around the frame. On the day we visited, we brought her a present from David Silcox, who runs Sotheby’s Canada: his book on David Milne, which she sat and studied closely, page by page. In this household, contact with the south has brought some good. She has loved her life.

Later, across town, we dropped in on Pitaloosie Saila, now in her seventies, who was presiding over a birthday party for her three-year-old great-granddaughter Eva (one of her twenty great-grandchildren) in a small house jammed with family of all ages. As macaroni and cheese was passed around, we talked about her family. She speaks English with unusual fluency—the legacy of a long childhood hospitalization in the south for tuberculosis—but for thirty years, she was also the Inuktitut voice of Cape Dorset radio, on top of her work as an artist and a mother. We watched her nephew assemble Eva’s new set of doll furniture, a birthday present purchased at the co-op, while Pitaloosie’s outspoken daughter Mary entertained us with stories about her son’s amorous entanglements in Iqaluit. We all laughed as Mary proposed a reality show about Inuit life, featuring Geraldo-style confrontations, DNA disclosures, and marital meltdowns. To me, this felt more like a hive than a house, a dense cluster of human energy filled with the honey of kindness. From my research, I knew that housing shortages were among the most pressing problems in the North, contributing to chronic rates of violence, addiction, and sexual abuse. Yet in this gathering of the generations I saw joy.

I found myself taking convoluted notes about the complex interweaving of family relations; many children are raised by relatives, and if you ask Inuit how many brothers and sisters they have you will often have to wait while they attempt to count them: half-siblings, adopted siblings, and blood relations who for one reason or another have grown up in other homes. The line between inside and outside the family is blurred, a conceptual demarcation evidently deemed irrelevant. It takes a while to grasp the underlying belief system: we all take care of one another.

A local hunter skins (or flenses) a seal, near Cape Dorset.

A local hunter skins (or flenses) a seal, near Cape Dorset.On the wall at Pitaloosie’s house hangs a striking old photograph of her and her late husband, Pauta Saila, a sculptor renowned for his soapstone carvings of dancing bears—or so they were described in the southern marketplace; in fact, they depicted polar bears balancing upright on unstable ice pans as they hunted seals during the spring breakup. Our mistake. On the wall beside it, she has a framed photograph of Peter Pitseolak, one of the first camp leaders to settle his family in Cape Dorset in the ’40s. An avid amateur photographer, he took hundreds of pictures of life in the community, an invaluable record. But if photography has been incorporated into the Inuit way of seeing, knowing, and remembering, the old stories still hold their power.

One day, Pitsiulak told me matter-of-factly about a cousin who was out hunting and saw two yellow female creatures coming out of the water and singing at the floe edge, their voices bewitching beyond his ability to describe them. At Pitaloosie’s house, we heard about a shaman who had tried to kill her mother through the agency of a weasel that morphed into flying black shapes and killed her baby instead. Pitaloosie’s nephew explained that this was likely why the stonecut workers had been spooked that morning by the discovery of a weasel on the studio’s back stairs; weasels are considered harbingers of malignancy. Pitsiulak says that on nights when the northern lights are blazing you can still hear Inuit youths in the streets whistling to draw the lights closer, or clapping to send them away. Draw the lights too close, the wisdom goes, and they can chop off your head. As I listen to these stories, dropped so casually into everyday conversation, I find it difficult to gauge how much traditional belief still lingers, but it’s obvious that these stories continue to bind the generations together.

And then there is the land itself. At the end of every muddy street, beyond the boats pulled up in dry dock in the off-season, beyond the muddy houses and the snow machines and the semi-feral dogs barking on their chains, beyond the long-abandoned, weather-battered Hudson’s Bay post, still with its signature red roof, lies a natural world of staggering beauty, which many in Cape Dorset know intimately and revere in a way that makes life whole. At the airport on my last day, an Inuit woman tells me that today is the day of three drips, when three or more consecutive drips from a snowy overhang mean the season has turned and the big thaw is coming. Their culture has always been one of careful noticing, of detailed looking—both in their relationship to the natural world and, later, in their artmaking, which brings that world so vividly to life.

Their world has been damaged, their way of life disrupted, infused with the toxic viruses of materialism, alienation, violence, and addiction. But it has not yet been destroyed. They were always better than we were at survival.

This appeared in the July/August 2012 issue.