The galleried corridors of glass cases displaying the latest Rosenthals and Cartiers aren’t there anymore. The fabled sirénes parading the lobby in furs and haute couture are gone. So are the swimming pool, the garden, the countless dining rooms, the ballrooms, the salons, the chorus of staff, the pockets of ferns draping the balconies, and the incredible ceiling that, like Zeus, contained it all. The Claridge Hotel, 74 Av. des Champs-Elysées, in Paris, is still there, though today it is flanked by a Planet Hollywood and a Marriott, and faces the Champs like a sullen schoolgirl. Some decades ago, the stomach of the hotel was carved up into arbitrary units, something like the map of Europe after the war. Now the hotel serves as a résidence, mainly for Mideastern oil barons and their furtive-looking wives, with the price tag for a suite sailing at over $1,000 a night.

The room I was hoping to find—that, in 1934, had witnessed the historic musical encounter between Django Reinhardt and Stéphane Grappelli, the makers of the Quintet of the Hot Club of France, an entirely new sound in jazz—simply doesn’t exist anymore, and what’s worse, it’s as if it never did.

Legends sit somewhere between the physics of the trick and the magic produced. Somewhere between the hat and the rabbit. Though the Claridge Hotel has forever lost its magic, the annual three-day festival in Samois-sur-Seine that celebrates the life of Django Reinhardt burns like a cudgel in flame.

Samois is a commuter’s distance from Paris and was home to Django for the last few years of his life. The neck of the Seine running through it is a perfect rendering of a Monet painting: dapples of light dot the surface of the water in a cadenced composition of this gentle, sloping hillside town. Django’s house is at the bottom of the hill, near the water, his grave at the top. Both are unremarkable except for the crowds that gather each summer.

The Django festival is a kind of pilgrimage for enthusiasts of Manouche jazz guitar. They come to pay homage to the man who created the music, reconstituted guitar playing and its position in the European jazz world, and, by virtue of his fame, almost singlehandedly transformed the image of the gypsy. Jazz is an American phenomenon; Django is one of the few non-Americans in the pantheon of jazz greats, and one of even fewer to have generated a school of guitar playing.

The town of Samois inaugurated the festival in 1968 as a response to the annual gathering of gypsy and jazz musicians that had begun spontaneously after Django’s death, in 1953. Django was forty-three years old when he left two sons, a trail of women, his wife, mother and brother, and a catalogue of recordings. This year, because it is the fiftieth anniversary of his death, the festival is particularly crowded. Thousands of people snake their way through fantastic amounts of dust and cigarette smoke, lining up at the makeshift stalls for bowls of paella, calamari/frites, moules, saucisses au vin, and bottles of very, very light rosés.

The events take place on the innocent, tree-lined Ile du Berceau, a slice of land, about the size of a department store, that has drifted from the mainland and is a footbridge away from the main road.

For three days in June, on this tiny, hyphenated island, dozens of scheduled performances are presented in an amphitheatre that seats about a thousand. The concerts are the initial attraction, with some of the world’s best jazz groups appearing, but the really compelling thing about this festival is what happens at the back of the island, in the tents. Here, gypsy-guitar makers from France and across Europe exhibit their instruments in paper-thin lean-tos, and festival attendees sample the wares.

All of the guitars are copies of the original 1930s instruments that Reinhardt championed, which were based on the Italian luthier Mario Maccaferri’s design for the French manufacturer Selmer. They differ from folk and classical guitars in their construction and design. Maccaferri created a soundboard that is curved in two directions and produces an unusually resonant tone. Also significant is the cutaway at the top near the neck and the parallel (instead of cross) bracing of the back. The instruments run anywhere from $2,500 to $3,500 (US), though an original fourteen-fret, oval-holed Selmer now has currency at $25,000.

Philippe Monneret is one of the guitar makers at the festival. He has a workshop in Mirecourt, the traditional seat of French lutheries. Philippe’s tent has a few examples of his work on display. He hovers around one of the Monoprix-issue lawn chairs set up in the middle of his tent. A man wanders in, picks up a guitar, and sits down. (It is always a man. I didn’t see one female guitarist.) He is middle-aged and from either France, Germany, or Britain, though he might even be an American or Australian. He is an amateur and probably belongs to his local Manouche jazz guitar club. He has mastered at least a dozen Django hits and can almost replicate the performance on the recording. He can’t read music and has never studied it formally. He is a dentist. He can play this music because he has spent thousands of hours learning it despite years of groaning from his children and actual disgust from his wife. He has snuck his discs on family vacations and now has to lie about where he’s been when he’s late for dinner, so he admits to having an affair. His wife forgives him because she is European and probably is having an affair. The North American isn’t so lucky. The words lawyers and papers come up over his lunch.

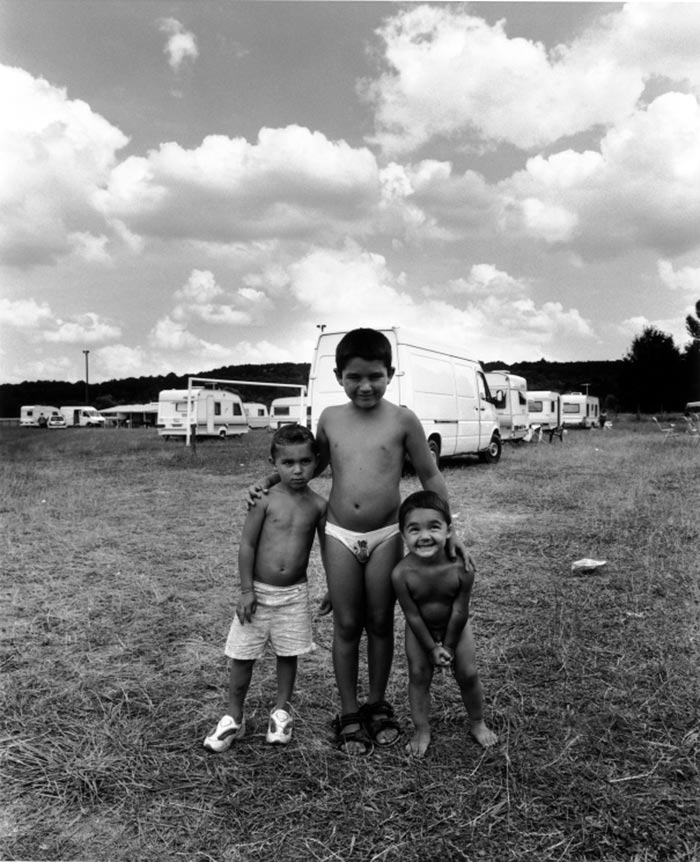

The dentist is obsessed, but this obsession has made him a remarkably fine guitarist, one who can tango with the best of them. When another player sits down in the tent, the guitarists launch into a number and, with an almost feline instinct, one person plays rhythm and the other lead. These men have never met, but they collude like conmen in a conspiracy of intimacy and pure pleasure. There seems to be no saturation point, and the encounters are repeated again and again, well into the night and well past the bedtime of the official festival. When one player gets up to leave, someone else slides into the empty seat with the desperation of a gambler waiting for a table at a casino. A violinist or accordionist wanders through. By now the crowd has swollen around the mouth of the tent. There is a ten-year-old Romany, a baby Django, playing rhythm. He looks almost comical because the guitar is at least three sizes too big on him and he can barely get his creamy adolescent arms around the belly. But he is ridiculously good and as the music moves into the familiar percussive frenzy of “Djangology,” a tune written by Reinhardt, its rhythmic motor pumps its way into the crowd. The boy takes the sixteen-bar lead and smiles like an adult.

Manouche jazz is a fusion of gypsy music and American jazz. It marries the two idioms by combining the forms and practices of jazz improvisation, which is American, with the exotic Eastern European scale system and the simple, mostly minor melodies of the Romany tradition. It is distinguished from other kinds of swing by the delicacy of the sound and by the inclusion of tremolos, harmonics, and gypsy rhythms. Django played with the upper partials of a chord—the seventh, ninth, and eleventh—suspending, augmenting, and lowering them. Though this is standard practice for jazz, the Manouche sound is distinct because he also revoiced and restructured many of the chords. They are leaner sounding and, along with the acoustic instruments and the absence of drums, give the music its particular transparency and charm.

Django was born Jean-Baptiste Reinhardt in a caravan on the outskirts of Charleroi, in Belgium, in 1910. In the grammar of Romany culture, he never went to school and travelled more than 3,000 miles as a child before his mother, Laurence Reinhardt, parked their house near the Choisy gate in Paris. Like many Romany women, his mother, nicknamed ‘Négros’ because of her dark skin and raven hair, never married his father, though they did have another child together, Joseph. In a photograph of her from 1939, she is reminiscent of Ma Barker, all steel and leather, her expression calibrated to permanent fatigue and suspicion. Whatever softness might have been part of her had been worn away by a life that never saw comfort or stability, a life of defending and protecting her own. She was carried along by the grand sweeps of Django’s life and by the Ferris wheel ride that is gypsy life.

As a boy, Django played the banjo at local cafés and on the streets. At the age of twelve, he got his hands on a banjo-guitar, and was getting jobs within a year. By the time he was eighteen, he was living the frantic hand-to-mouth existence of a gypsy musician, which was threatened when, two weeks before the birth of his first child, he nearly died in a fire in his caravan. Django languished in a nursing home for over a year and eventually got most of his mobility back. But the last two digits of his left hand were permanently paralyzed. He taught himself to play the guitar with only two fingers, dragging the other two useless stumps along the strings and using them to dampen the sound. He developed a technique for playing unplayable octaves with his thumb that would become part of his signature virtuosity and the envy of all guitarists. Some fanatic Djangoists actually play with only three fingers.

When Reinhardt and Grappelli got together and formed the Quintet of the Hot Club of France (qhcf), in 1934, the idea of a string-based acoustic jazz ensemble was extremely radical. Until then, the guitar was pretty much relegated to the rhythm section, only occasionally taking a solo. Django moved the furniture. He got rid of the piano, sax, and drums, moved the guitar to centre stage, and designed a space for the violin. And he anchored it all with two rhythm guitars and a string bass. The sound was entirely new, so the music had to change as well. Django composed hundreds of songs that spotlight the guitar and developed a guitar technique and a style of improvisation that reminds me of Oscar Peterson’s or Art Tatum’s: completely organic in the context of the music, but supernatural on its own.

As a composer, Django was taken by the aesthetics of impressionist music, by the texture of the sound, and by the move away from the strict forms of harmonic composition dictated by the diatonic tonal system (major and minor). Debussy and Ravel were already experimenting with the whole-tone scale and with polytonality, the simultaneous use of different keys. Polytonality creates a vague tonal centre, and the ear wanders around not quite knowing what key the song is in. The basic key might be C, but you are also hearing, depending on the bass note, a number of other keys. The ground literally shifts beneath you, and one of the really liberating aspects of this technique is that the harmony can modulate from any one of these keys.

Django couldn’t read music, so he didn’t analyze Bach or pore over the scores of Debussy and study his composition techniques. But he had an extraordinary ear: he could apparently sift out which instrument in an orchestra was out of tune. He wouldn’t tolerate wrong notes and regularly dismissed musicians who committed that crime. And when he heard music, he intuitively deconstructed and isolated the sonorities. He listened to the vertical and the horizontal lines, to the melody and the harmony and their synthesis, and I imagine he would visualize them. In the same way that a mathematical theorem is articulated through its proof, so the calculus of music is unravelled through its architecture. Django was keenly attuned to the formal structure of a piece. He would have automatically calculated the number of bars in the thematic material, where it modulated, when it was repeated, whether it was inverted, how it developed. This made it very easy for him to copy what he heard and to imitate a compositional style, and he would spend hours at the piano improvising in the manner of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century composers. He loved Bach because of the contrapuntal nature of the music. Bach wrote music from the bottom up and then dressed the top with ribbons of sound.

“Rhythm Futur” is an unusual piece written by Reinhardt. It was ahead of its time and shows Django’s harmonic inventiveness. The piece uses two standard jazz chords, both in the tonality of C: a flat five in the bass, juxtaposed with an augmented five on top. These chords are not naturally compatible, though they’re from the same family. When played together, they destabilize the tonality of the piece. They might be used together in more conventional hands, but only in passing. Django sustains the harmonic tension for the first half of the piece, spinning out the melodic line in wild threads. In the less complicated ballad “Tears,” a traditional Romany song arranged and performed by Grappelli and Reinhardt, the introduction of a few American blues notes keeps a simple melody of regret from becoming sentimental.

Joselito Loeffler and Mito Loeffler are two professional gypsy jazz musicians from Strasbourg who are at the festival in Samois. They are sitting on the terrace of one of the only restaurants in town, which, incidentally, has one of the few legitimate bathrooms, and then, only for patrons. I had snuck in to use the facilities, and when I came out, found a spot among the crowd that was beginning to form.

Mito looks like what I’d imagined Django to look like before I’d seen pictures of him: modulated waves of black, black hair, angled cheekbones, moustache, copper skin like old naugahyde, and benevolent, ancient eyes. In fact, his cousin, Joselito, who is younger and lighter-skinned, looks more like the Reinhardt clan. Joselito is squatter and thicker than that family, his features generally less refined, his hair cut like a general’s, but he has the same prominent forehead, the same circumflex of a moustache, and the same leading-man lips.

The two cousins don’t usually play together—both have their own groups and tour extensively—but, on that sundrenched afternoon, we were treated to some of the most exquisite exchanges between musicians I’ve ever heard. Maybe this is what it was like to hear Reinhardt live: the elegant improvisations, the lightning technique, the landscapes of colour in the sound. There are recordings of the qhcf in which it is almost impossible to tell when the violin solo ends and the guitar begins.

By the latter half of the Thirties, swing music had become the order of the day, and the Quintet of the Hot Club of France was bouncing around the borders of Europe, playing to packed houses and enjoying the bounty that comes with fame. It was not uncommon to hear Django’s tunes whistled in the streets. Bolero, one of his orchestral compositions, was performed on the same bill as Ravel’s masterpiece of the same name, and the reviews likened Django to the French school. Gertrude Stein invited him to her elite salon, where he entertained Picasso, Anaïs Nin and Henry Miller, though the real aristocracy for Django was Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong (he cried the first time he heard Armstrong), and he thought the world of Frank Sinatra.

Throughout all this success, Django never lost the caravan in him and was comfortable in the George V hotel, where he was a frequent guest, only when he had a shipload of his ‘cousins’ camp out on the floor. His taste for fat, expensive American cars was congruent with the often outrageous movie-star fees he demanded. And he never carried his guitar. That was left to his brother Joseph, who played rhythm in the original qhcf.

The social patterns that underscore the Romany cultural fabric were the ideal grounds for Django to explore the backstreets of his imagination. They provided him with untempered access to himself, free of the constraints of influence and the pressures of conformity, and gave him a passage to the labyrinth of his talent. He embodies the extremes of that compass—from the untamed to the cultivated, the chauvinist to the supplicant, from shame to defiance, obscurity to magnificence.

He couldn’t read or write and never learned. Grappelli eventually taught him to write his name—his signature is as primitive-looking as King John’s on the Magna Carta—and to subdue his taste for overly festive outfits. Once, when Django was negotiating a contract, which he was reading upside-down, he pointed to a paragraph and demanded that the manager scratch the clause. That clause guaranteed the band return fare from the tour. Grappelli never managed to quell Django’s lifelong appetite for gambling, and on occasion had to drag him from a game to get him to a recording session. Django was also a heavyweight at billiards and at one point even contemplated it as a career.

Doted on by his mother and in-dulged by his wife, Naguine, he was impulsive and imperious, smoked so much that there isn’t a photograph of him that doesn’t include a cigarette, and regularly gambled everything to nothing. He could disappear for long periods without the slightest provocation, and then be found days later, fishing or painting by some simple stream. In some ways, he was a prisoner of the deep swings of his creativity, the gigantic ropes of empty and full.

By the time the Second World War broke out, Reinhardt’s reputation spared him from persecution by the Nazis, who were rounding up gypsies across Europe. He played the ‘subversive, degenerate swing music’ all through occupied France, forming different bands and playing to overstuffed houses. Every second Romany claimed to be his cousin, or, in the case of a few in concentration camps, to be him.

But, for a long time, Django had harboured a dream of a bourgeois life in New York, where he would live off the fat of his talent in some magnificent apartment and patronize expensive restaurants, only occasionally picking up the guitar. He had even detailed for himself the music selections for every meal: Bach in the morning, Stravinsky or Debussy for midday, and Glenn Miller as an after-dinner mint. So, when an invitation arrived in 1946 from Duke Ellington to tour with his band, Django dropped everything, which, at that moment, was a contract to write music for a film, and set off with bumpy bravura for his first American adventure. He didn’t pack a toothbrush or a guitar, sanguine in his belief that various American guitar manufacturers would vie for the privilege of having him play one of their specially designed instruments. But Django’s fame had not, apparently, preceded him. After a few days in the US, he bought a toothbrush and, reluctantly, soon after, a guitar. He proved more comfortable with the former than the latter, and his American experience was scarred by feelings of isolation and disappointment, though he played to enthusiastic audiences across the wide girth of the country. When the band got to Carnegie Hall, by far their most important date, Django didn’t. He wandered on stage two-and-a-half hours past curtain time without a guitar, to the shock of Ellington, who had already made a public apology for the prodigal gypsy. Django was quickly given an instrument, which he had no time to tune, and he delivered a performance below his usual standard. The New York papers were not kind. It marked a turning point in his career.

Django hung around New York for several months after the tour, playing at the Café Society Uptown, and waiting for an offer from California that never materialized. The swing era in jazz was already coming to a close. Manouche would eventually take its place in the filing cabinet of music history, actively surviving only by the romance of a few. The golden age of jazz, which had coincided with the rise and fall of the Third Reich, when it was the anthem of liberation and the music of the everyman, had lost its mass appeal. Bebop and other hybrid forms of jazz were taking over, and Django would no longer be immune to the conventions of professional conduct or be tolerated as an enfant terrible. The demand for his music was drifting away, like images in a dream. Homesick and disillusioned with America, he went back to France and moved to Samois, because the fishing was good and because he wanted to paint. The noise in his life was overwhelming him.

At the beginning of the last century, the pristine hillside town of Samois became a weekend retreat for rich Parisians who constructed extravagant estates along the road facing the Seine. The mansions stand in sharp contrast to the unspoiled medieval architecture of the rest of the village, which borders the Fontainebleau (pronounced ‘blow’) forest.

On the second day of the festival I navigated my way up the hill through the skinny cobblestoned streets in thirty-four-degree heat and inappropriate shoes, in search of the local patisserie and, later, the town cemetery, where Django is buried. The tarte au raisin was disappointing, and I sympathized with the town’s 2,200 inhabitants, whose options for a night out in Samois are limited to the bakery, the bar, or the telephone, all of which are in the square. The single hotel, The Hostellerie du Country Club, is fully booked in September for rooms in June, so the vast majority of tourists who attend festivals there—and there are several such events—look for accommodation in the nearby town of Fontainebleau.

I had come into town from Fontainebleau, where I was staying. Samois has set up a courtesy shuttle bus, the Navette, to ferry visitors to and from the festival. They fail, however, to provide a bus schedule. What is offered, instead, is the train schedule from Paris to FB, from which you have to decipher the arrival times. This is written in code (no legend, of course), which runs vertically on the left-hand side of a graph that is right out of a high-school math exam. It is a series of letters and apparently translates into something like this: Q means not on Sunday. R means only on Tuesday and E means every day except Saturday, which is V. Even if you could crack the nut, there is no guarantee of a bus. I learned this the hard way. So did at least twenty Brits and a muster of Europeans, all of whom expressed “learning things the hard way” with their own distinct national character.

We did eventually get on the Navette, a wide-hipped vehicle whose claim to air climatisé was something of an interpretation, and discovered how difficult it is to negotiate Samois traffic during the festival. Hundreds of cars line both sides of the thin strip of road for kilometres. And everywhere there are people walking, guitars and tents slung over their backs. At some point, the road became impenetrable. A young Honda Civic was straddled on the right-hand side of the road and a ripe old Peugeot on the left. It was impossible to go forward. The bus driver, whose natural mien obscured the line between man and Rottweiler, fugitive tufts of fur creeping out of his undershirt, slammed on the brakes, barked some obscenities, stomped out of the bus, and with the help of two passengers simply lifted the baby Honda from its spot like a schoolteacher removing an offensive child from the playground.

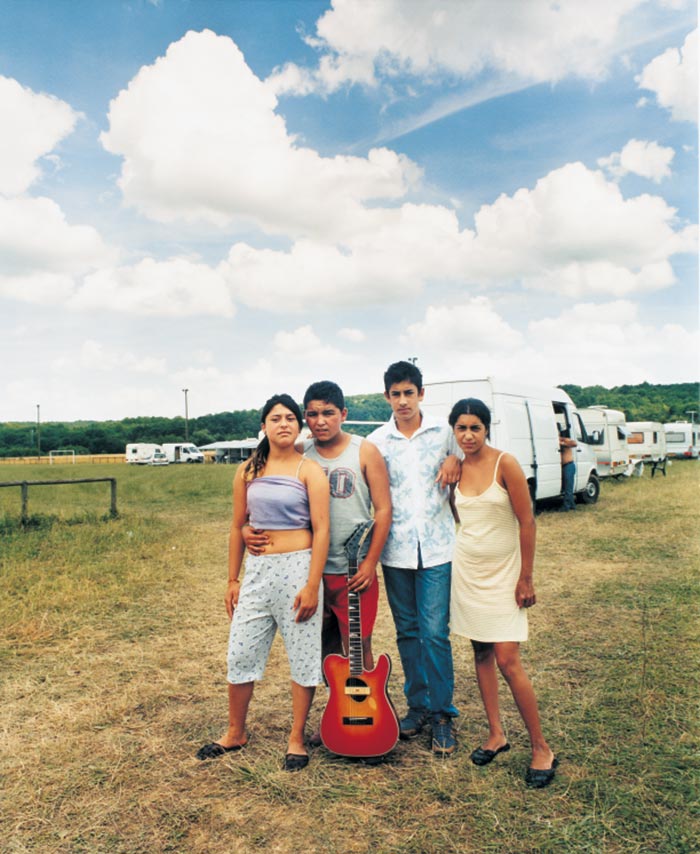

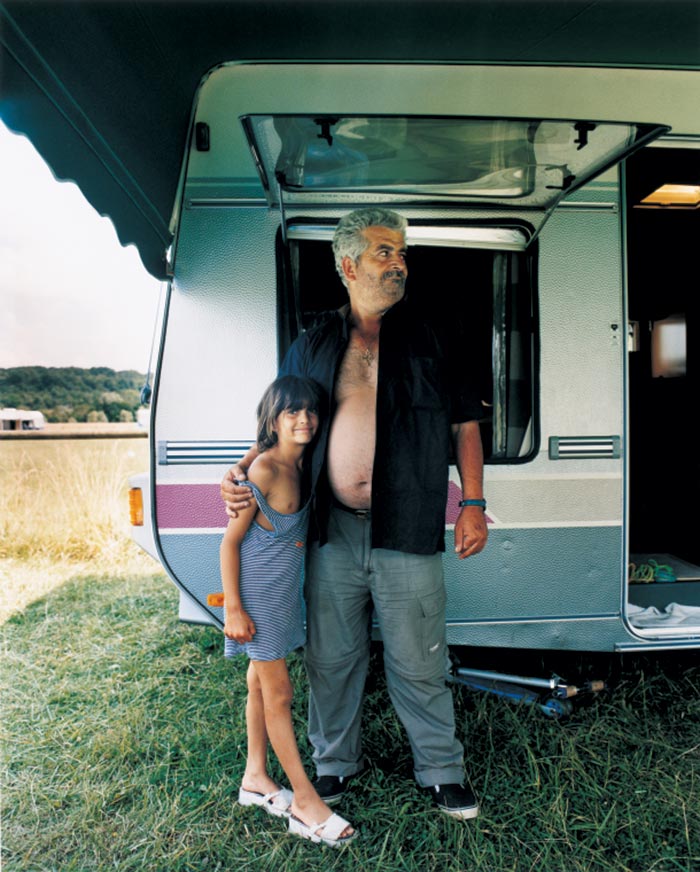

After an exhausting climb from the bottom of town, I reached the cemetery, which sits on the slow, stubby terrain of a neglected field. Scorched and ragged, the land looks like an unkempt beard. The graveyard occupies half of the space; the other half is, because of the festival, temporary housing for the Romany. The caravan has now been replaced by the mobile home and, at two o’clock in the afternoon on a day chaperoned by dangerously oppressive heat, little Hibachi grills set picnic-style in front of a crowd of tired old trailers were already preparing the evening meal. The place was humming with onion.

The Reinhardt family plot is one of the largest in this modest, orderly graveyard typical of any small town’s, the wooden crosses and occasional slabs of stone in tidy rows, the chaos of grief buried in its ordinariness. Django’s memorial is a sizeable marble monument, decorated with a hero’s supply of fresh flowers and adorned with photographs of him. It has become a tradition for guitarists who visit the grave to leave a guitar pick, and the surface of the stone is covered in tiny plastic triangles. The dates on the inscriptions duly chronicle the delicacy of the Reinhardt male constitution; Django died at age forty-three, and his two sons, Henri and Babik, in their early fifties, only his brother Joseph surviving his seventies. Django’s wife and mother lived well past their men.

Music has the power to transmute real time into suspended moments. Great performers usher us through these dimensions and, in a teardrop of sound, we slide through time, sometimes transported to a collective history, sometimes to our own personal archives. In that attenuated moment we are cradled by the magic of eternity.

On the Ile du Berceau, the Romany clans filter through the sea of white faces—the dentists, the fanatics, the Django copiers, conspicuous as buttons on a coat. Here they are the authentic voice, the legitimate heirs to the giant of Django. They accept the attention with a mixture of humility and earned indifference. It’s as if this one man had released them from the burden of their history. To the artists among them, Mito Loeffler, the Rosenbergs, Bireli Lagrene, to name a few, Django gave passage to themselves and to the open seas. “Nous lui devons tous,” said Mito.

Somewhere along the Seine, Django looks on and smiles. Somewhere between the hat and the rabbit.