Sometime in 2007, Lucia O’Sullivan, a psychology researcher at the University of New Brunswick, had lunch with a friend and colleague from campus. Her friend worked as a doctor at the university health centre, and for the past couple of years, she had noticed a concerning occurrence among young female students: they would come in for a routine gynecological exam saying nothing was wrong, and when the doctor looked, she would find vulvar fissures—small cuts on the women’s vulvas, often caused by lack of lubrication during intercourse. When she asked about these wounds, a number of patients would reveal that sex was often painful or uncomfortable but that they had never considered it a problem.

Listen to an audio version of this story

For more Walrus audio, subscribe to AMI-audio podcasts on iTunes.

The more the doctor asked her young patients whether the sex they were having was a positive experience, the more concerned she became. For years, she noticed this happening—that some teenagers and young adults were having unpleasant sex yet continued to do it—but she didn’t know how to handle it past speaking to her patients one on one. Then, curious whether anyone had ever researched the phenomenon, she discussed it with O’Sullivan over lunch.

O’Sullivan, who was until recently a Canada Research Chair in adolescents’ sexual-health behaviours, has studied the relationships of teenagers and young adults her entire working life, and her friend’s story struck a chord. She had just returned from working in the United States, where sex research is notoriously underfunded and stifled by a reluctance to have open discussions about intimacy. It occurred to O’Sullivan that from her new position in New Brunswick, she had the freedom to research a question no academic had comprehensively investigated before: Are young people enjoying the sex they’re having?

Since that lunch date, O’Sullivan has devoted a large part of her research to finding the answer. “We decided to conduct a preliminary study, and we realized right away that sexual functioning”—the scientific term for how the body reacts during sex, including erection and orgasm—“in young people is notably bad,” she says. She found that people between sixteen and twenty-one years old consistently experienced problems, including pain and lack of interest. For many of them, those problems affected their lives in a substantial way: in a survey published in 2014, 50 percent of teenagers surveyed described a “clinical level of distress.”

Their difficulties weren’t related to poor hookups or inexperienced sloppiness: O’Sullivan found that most sex between young people occurs in a relationship setting. And teens of all genders were struggling with significantly low amounts of satisfaction and desire to have sex in the first place. A study from 2002 about Viagra abuse found that a large number of users were teenage boys. This study, which informed O’Sullivan’s own, seems to show that young men feel pressured to pursue sex even if they don’t want it.

The findings were “eye opening” even for O’Sullivan, and they serve as a reminder of how little is understood about teenagers’ relationships to sex. Conversations in the public sphere about sex—whether related to workplace harassment policies, educational curricula, or criminal trials—are so political and personal that they have become increasingly removed from the reality of people’s lives. This is especially true when the conversation is about young people: acknowledging that teenagers are sexual beings taps into broad cultural anxieties—teen pregnancy, loss of virginity—that many are still not ready to grapple with.

When it comes to education in most of Canada, the unwillingness or inability to engage with reality has meant focusing largely on prevention, birth control, and STIs (the least controversial topics) while overlooking any kind of desire or incentive to please. But this approach leaves many teenagers in the dark, and it overlooks the fact that sex between adults will inevitably be informed by the experiences—whether positive or negative—they had when they were young and learning about sex for the first time.

Meanwhile, society’s understanding of sex has long been dominated by the pornographic ideal of male pleasure, and contemporary conversations about rape culture have further muddled our understanding of relationships and sexual acts. We generally know what not to do, and we know what we think sex should look like. But many young people (and often adults too) have no idea how to start, or why to start, or what to do once they’ve started. O’Sullivan’s research is likely showing us the results of that reality for the first time: burdened by a fear of speaking about sexual pleasure with young people—and by an occasional inability to understand or even explain it—society may have set them up for a lifetime of unsatisfying or even painful sex.

“It’s scary as a parent to talk about sex, but I think we shouldn’t avoid it,” says Carlyle Jansen, a sex educator from Ontario who founded Good For Her, a Toronto-based shop that offers sexuality workshops and sex products, in 1997. Jansen and her colleagues offer courses for adults about everything from female ejaculation and anal sex to consent and online dating. She also has two sons, and as a family, they’re learning how to speak about sexual pleasure and relationships. She believes those are the conversations that are missing from her sons’ education at school.

Jansen has learned that teachers had taught them about the fallopian tubes and the vagina and condoms but not about the clitoris or the logistics of actually having sex. From speaking with people who attend her workshops, Jansen knows that many sexual challenges are not particular to women; men have often come to her for advice about pleasing their partners and coping with various difficulties. Jansen wants her sons to be comfortable with sex and to understand boundaries and respectful interactions. Now, when the topic of sex comes up at home in song lyrics, on TV, or on social media, as it is wont to do, she tries to introduce discussions about intimacy and relationships. She will elaborate about the pressure some people feel to perform, the value of pleasing one’s partner (“if someone goes down on them, then they go down on them too”), or the different ways that sex can be had.

A few months ago, Jansen and her kids watched an episode of Modern Family that showed the character Alex Dunphy, a young teenager, receive her first kiss from a boy without her consent. The show brushes off the incident as a cute encounter: Alex later confronts the boy and kisses him back. But Jansen paused the scene and used it as an opportunity to discuss the value of consent and communication with her sons. Seeking pleasure for oneself, she told them, should not be separated from the pleasure of one’s partner. “When you do talk to [your children], they know it’s okay to bring stuff up with you,” Jansen says. “If you don’t talk to them, they’re going to talk to their friends who have horrible information. They’re going to search the internet and find porn instead.”

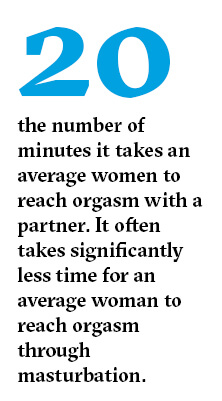

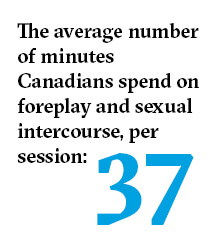

While the idea of a parent talking so openly with their teen about sex might seem novel, it’s also a necessary part of helping them to navigate healthier sex lives—and pleasure does, arguably, influence health. The better understanding a teen has of both, the better foundation they have for a holistic sex education. A teenager’s willingness to practise sex safely, for example, could strongly relate to the type of sex they think is normal and the messages they receive from their partners. And while traditional sex-education curricula might introduce students to human anatomy and topics such as STIs, they often treat those elements as completely separate from the actual act: a teacher will explain how a woman can become pregnant but not which angle of penetration might be most comfortable or pleasurable for her. They will explain how sperm flows from the testicles to the penis but not how someone might approach discussing premature ejaculation with their partner.

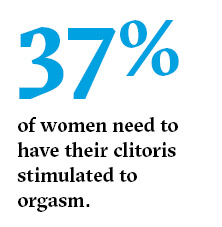

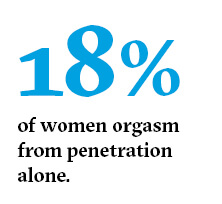

Many of the difficult conversations about sex today are related to the differentiation between what is natural and what is not: we are much less likely to overcome abuse if we don’t know that it’s a problem in the first place. It sometimes takes a structured classroom setting to learn how to identify good, bad, and everything in between, to learn how to have proper conversations about consent, to learn how to be close to someone after trauma, and to learn how to be intimate without sex. It might also take an educated instructor to teach people that clitoral orgasms are real orgasms (a surprising number of women don’t think so), that some men can have multiple orgasms, and that different people might respond differently to different acts. These are all lessons that are easily available to adults through workshops such as Jansen’s or in popular books and online forums. Yet young Canadians, who are much less likely to access those resources, are excluded from those conversations.

This is where pleasure education comes in, promoting a more comprehensive program where the teacher acknowledges not just biological elements of intercourse but also why people do it and what it might look like—including oral sex, masturbation, and other aspects of intimacy that are standard facets of the human experience but have little to do with pregnancy and reproduction. This philosophy—that young people should learn about the enjoyment of sex at the same time as safety, prevention, and birth control—was introduced in North America in the late 1970s, but the inclusion of pleasure education really took hold in 1988, when Michelle Fine, a professor of psychology at the University of Pennsylvania at the time, published a seminal paper on the “missing discourse of desire” in public-school education in New York City. Her research cemented the concept of sexual education as an integral part of feminism. Speaking with young women about their agency and sexual enjoyment, she argued, would empower them to reject the idea of sex as something they reluctantly gave away to persistent boys and men and to see it instead as something they might enjoy.

As Fine pointed out in her paper, sex educators in the early 1900s thought that, for example, “a normal young woman” would never masturbate. Even more “progressive” courses of the ’80s and ’90s focused mostly on biology and “male heterosexuality,” excluding any other sexual orientations or genders. Feminists at the time argued that pleasure education was essential for the health of young women; it would help them understand their own bodies, learn to navigate a complicated world of sexual politics, and enrich their lives. Over time, as researchers acknowledged that the problem extended past the experiences of young women, pleasure-education advocates also incorporated the experiences of young men and those of other gender identities and sexual orientations, all of which are typically overlooked in traditional sex education. Studies showed promise for the effectiveness of such an approach, but in North America at least, the idea has largely remained controversial and marginalized. Then, and now, parents and politicians have been scandalized by the thought of speaking with children about orgasms, same-sex intercourse, and other topics that were rejected by more traditional ideologies.

Today, many other countries including Sweden and the Netherlands, have incorporated comprehensive sex education into their classrooms. Researchers generally agree that it is the most effective way of helping teenagers and young adults of any gender to have safe sex, prevent coercion and discomfort, and even avoid pregnancy and STIs. (In the Netherlands, for example, where 92 percent of men and 75 percent of women today say they “enjoy sex very much,” rates of STIs and unplanned pregnancies are comparatively low.) But there is a gap between the academic discourse in Canada and local classrooms and doctors’ clinics, where pleasure is rarely touched upon at all. Most provinces and territories teach about the logistics of sex—the body parts, birth control, safety—but nothing about the enjoyment of the act or the relationships that form before, during, and after.

Ask young people what they want to learn about in class, and they’ll answer that they’re curious about how to have sex and communicate about it openly; most of them will decide whether or not to do it regardless of education, but the way they do it is what could change based on the information they receive. Louisa Allen and Moira Carmody, researchers in New Zealand and Australia, call this the “gap” between what teenagers talk about in school and what they do among themselves. “Young people surveyed by researchers from a range of countries are consistently clear about what they want to know, what is over-emphasised in sexuality education and what is omitted,” they wrote in a 2012 paper. Teachers would avoid discussing desire and the “emotional aspects of sexuality,” for example, while belabouring lessons on reproduction and the dangers of pregnancy, abortion, and STIs.

These findings are strikingly similar to the results of a Toronto youth survey published in 2009. Planned Parenthood Toronto interviewed 1,216 teenagers and found that the top three topics they had learned about in school were HIV/AIDS, STIs, and pregnancy and birth control. But the top three topics youth had wanted to learn about were healthy relationships, HIV/AIDS, and sexual pleasure. Less than 30 percent reported having learned about relationships. No group reported learning extensively about pleasure. The irony, as Jansen, who sometimes teaches sex education in alternative schools, points out, is that “when you talk about safe sex, teenagers tune out. But you can sneak all the safe stuff in when you talk about pleasure…they are much more receptive.” It’s easier to talk to a classroom of curious students about using condoms when you also talk about what comes before and after the condom and what open communication about safety might look like.

This kind of shift in perspective, which treats sex as a complex act grounded in mutual respect and desire, does more than teach students about orgasms. It also reorients the sexual experience, reminding teenagers that the primary motivation for sexual acts is, in most cases, the pursuit of pleasure and intimacy—so, if the sex they are having is neither pleasurable nor intimate, there might be something wrong. If someone is never taught that sex is something they should enjoy, they might be more willing to accept pain and discomfort as a typical experience. And, if they are never taught that their partner should be enjoying it too, they might develop habits without any regard for whoever else is involved. O’Sullivan’s research in New Brunswick, which was the first comprehensive research of its kind in North America, likely shows the consequence of the lack of pleasure education in classrooms: many of the teenagers and young adults she and her colleagues surveyed had “never ever been told how to have pain-free, pleasurable sex”—and so they often accepted discomfort as a natural part of the experience.

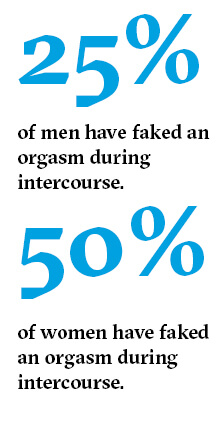

Out of the adolescents O’Sullivan and her colleagues surveyed for their 2014 study, just over half of those who were sexually active reported a problem such as pain or lack of satisfaction or ability—a higher rate than in comparable adult samples. There was no significant difference in rates between boys and girls: while girls had difficulties with pain, sexual coercion, and lack of orgasm, boys struggled with performance, low desire, and low satisfaction. In a follow-up study in 2018 about how young people understand and address these problems in sexual functioning, O’Sullivan found that most had never discussed the “positive aspects” of sex with their parents and didn’t know where to turn for information, nor did they know how to lessen the impact of these problems on their lives and relationships. Eventually, young men and women would accept their predicaments as a natural part of life, and they would develop a variety of coping mechanisms. As one young woman told O’Sullivan, sex was “not bad,” but it also felt like “losing your virginity every time—it’s like a ripping.” Sex to her was like “a science experiment,” and yet she continued to have it.

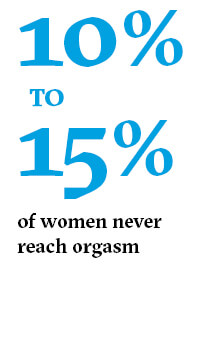

Low satisfaction and desire don’t necessarily go away as teenagers get older—nor does pain. O’Sullivan and her colleagues found that the problems people experienced as young adults likely followed them into adulthood, which might explain why adults have notoriously high rates of sexual problems. It’s something we rarely talk about, especially because adults are expected to figure these things out on their own. But, in reality, people don’t enjoy sex nearly as much as popular media would have us believe. In 2004, a global study of adults over forty in twenty-nine countries revealed that around 40 percent of women and 30 percent of men faced challenges such as low interest, inability to orgasm, and early ejaculation.

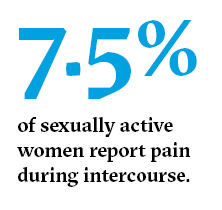

Those are just a few of the problems starting to gain public awareness. Doctors have, for example, only begun to understand the sheer number of women who have vulvodynia, meaning they experience persistent, unexplained vulvar pain. Many women with vulvodynia endured excruciating sex for years before finding an accurate diagnosis—which shows not only how little we know about certain parts of our bodies but also how much someone might be willing to put up with if they think it’s normal or unfixable.

Mhairi Kay, a twenty-nine-year-old occupational therapist in Toronto, has a retroverted uterus, meaning her uterus is tipped backward toward her rectum instead of her stomach. Ontario’s educational system taught her nothing about what that would mean for her sexual life. Her mother would ask her if she was having safe sex, but they never spoke at length about what she was dealing with. Kay found sex sometimes uncomfortable or unenjoyable, but she felt that “if I wasn’t having an orgasm or wasn’t into it, it meant my body was broken or I was too much in my head.” Kay felt like an anomaly. It wasn’t something she ever spoke about at school or with friends. She thought she would have to deal with the problem alone or not at all.

Then in her early twenties, she visited a doctor who explained to her for the first time what having a retroverted uterus meant. He walked her through which positions might work best and how to address that with her partner. “That changed the way I viewed my body,” Kay says. “I finally understood my own body and pleasure.” Over time, she become more communicative with partners. “I now know the difference between good and bad sex. I’m less willing to accept bad sex,” Kay says. “I don’t feel shame anymore.”

But despite this change over the past few years, Kay still found pleasure to be a challenge: it’s often difficult for her to identify why something isn’t working or to instruct a partner on what to do differently and how. That’s why, in September, Kay attended a workshop at Jansen’s Good For Her, which offers a kind of sex education for adults, filling the gap between the pragmatic preventative measures people were taught in school and the knowledge many need to find satisfaction in the romantic and sexual world.

Being able to learn about anatomy in the context of pleasure—not just a body part’s reproductive function but also its sensitivity and pleasure points—was elucidating and empowering for Kay. “It helped me feel more confident that I could perform, because I have a better understanding of where everything is.” In a group setting, she heard women talk about how to overcome challenges such as poor body image and low confidence in the bedroom. She left the class with a better understanding of sexual dynamics and how to acknowledge her own desires.

Alternative workshops such as the ones offered at Good for Her are often treated as fringe and risqué. And the academic circle, which is composed of researchers such as O’Sullivan, is often excluded from public forums. Despite her research and multiple calls for the implementation of comprehensive sex education in Canada, the majority of school curricula haven’t changed based on her recommendations. The public narrative across most of Canada, propagated by school boards, parents, and politicians, is still largely stuck on the debate about whether to even include sexual orientation—let alone discussions about blowjobs—into classroom conversations.

These worlds are all so separate that, before speaking with me, O’Sullivan had never heard of Jansen’s workshops, and Jansen had heard of O’Sullivan’s research only in passing. And yet the two have reached the same conclusion through their decades of work: we need to teach teenagers about sex more comprehensively. The fact that we don’t do so now has a serious impact on their romantic and sexual experiences, and possibly will for the rest of their lives.