Dany Laferrière remembers the confusion he caused among locals after landing in Montreal in 1976. “They didn’t understand,” explains the Haitian-born author in Working in the Bathtub, a new book of interviews, “how someone who worked in a factory, who was black, an immigrant, from an extremely poor country like Haiti, could want to be a writer.”

What happened next may well have puzzled Laferrière’s neighbours even more. His 1985 debut, How to Make Love to a Negro without Getting Tired, made him a sensation. Irreverent and picaresque, set in Montreal’s Carré Saint-Louis neighbourhood, the novel mirrored Laferrière’s life during the 1980s: a Black man from Haiti yearning to be a great writer. Early in the book, the narrator declares himself a “Negro brimming over with unappeased fantasies, desires and dreams. Put it this way: I want America. Not one iota less.” Laferrière got a version of his wish: his fame exploded in Quebec and France, in part because of the controversy generated by the book’s title. (Later titles include Why Must a Black Writer Write about Sex? and I Am a Japanese Writer.) Laferrière has since published dozens of books, winning both France’s Prix Médicis and the Grand Prix du livre de Montréal with his 2009 international bestseller, The Return.

Uncertainty, however, still stalks Laferrière’s career, especially in the rest of Canada, where his reputation seems to have stalled. The last book of his translated into English appeared eight years ago (The World Is Moving around Me, a 2012 memoir on the Haiti earthquake). A total of fourteen titles remain untranslated. As scholar Lee Skallerup Bessette noted in her introduction to Dany Laferrière: Essays on His Works, Laferrière’s notoriety turned him into an object of cocktail-party fascination, someone whose celebrity was premised on the racial dimensions of his books rather than on his literary gifts. He became a symbol of trendy otherness—he was even offered a gig as a TV weatherman in Quebec. But, while his stature grew, consideration for his books did not. “I’m very famous,” Laferrière is reported to have told his French publisher, “but not many people read me.”

Laferrière’s Anglo neglect was on stark display in 2013, when only a scant number of Canadian dailies covered his appointment to one of the most exclusive organizations in the world: the Académie française, a forty-member council founded in 1634 to protect and preserve the French language. The seat is a lifetime posting, and previous members—usually known as “immortals”—have included French luminaries Voltaire, Victor Hugo, and Alexandre Dumas. Laferrière was the first Haitian and the first Quebecer to be elected, yet the New York Times devoted vastly more space to the news than any of our national papers did.

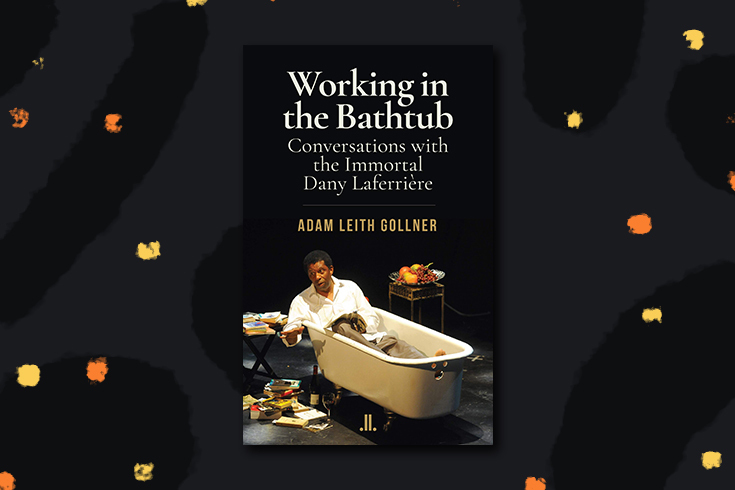

One answer for why Laferrière’s rise has been all but overlooked in English Canada may be found in Working in the Bathtub. In his interviews, Montreal writer Adam Leith Gollner traces the various ways Laferrière has confounded literary expectations, often at the expense of popularity. As he and Laferrière talk—touching on everything from Laferrière’s obsession with coffee (drinking it, he says, is “not merely a drug; it’s an art”) to his theory of “dandyism”—it’s hard not to get the sense that Laferrière may be paying a price for storytelling that flagrantly mixes fiction and memoir. Laferrière calls his oeuvre of unclassifiable, self-referential books “an American autobiography.” The lifelong project features recurring plots (such as a stand-in called “Dany” who, in at least two novels, returns home to Haiti for the first time) and a stream-of-consciousness form that shapeshifts from verse to dialogue to essay—all of it held together by Laferrière’s coy humour. The result, says Gollner, is “as postmodern as it is electrifying.”

It’s not just Laferrière’s genre-bending innovations that risk alienating him from English Canadian tastemakers. It’s also his hostility toward one-dimensional conceptions of Black, immigrant, and Haitian life. As this year’s Scotiabank Giller Prize winner, Souvankham Thammavongsa, noted to the CBC, “Whenever we encounter stories of immigrants and refugees, they are always sad and tragic.” Canadian publishing catalogues show the continued ascendency of books that delve into the struggles of racialized groups. The terms often used to describe such books—“raw” or “authentic” or “intimate”—tend to sideline aesthetic achievement in order to highlight insider reportage. In late August, eight of ten Canadian nonfiction bestsellers, according to the CBC, were by Black, Indigenous, or Muslim writers—all of them featuring tales of trauma: the practice of police carding, for example, or the suicide crisis among Indigenous youth, or the ordeal of Pakistani asylum-seekers fleeing to Canada.

For Laferrière, who fled Haiti at twenty-three after his friend and fellow journalist was assassinated, racialized lives are not solely mired in misery. There is also exhilaration and joy. Defending the validity of happiness for the underclass is the radical pursuit of Laferrière’s work. It’s a pursuit rooted in his upbringing under a dictator. “I severed my ties with Haiti,” he tells Gollner, “to break the great sorcerer’s spell—that of the dictator, who says, You will be obsessed with me, and you will think only of me. I can do other things, but you, you will think of avenging yourself, of getting worked up, and you will think of nothing but me.”

The refusal to play into this doom-and-gloom has put Laferrière at odds with a central bias of English Canadian writing. “Why can’t happiness be just as valid as bad feelings?” he asks.

Voicing the concerns of different diasporas across the English-speaking world, British writer Monica Ali has often pointed out the pressure to keep writing about the Bangladeshi community she explored in her first novel, Brick Lane. “If you’re a writer of color,” she wrote in a recent essay, “you’re only supposed to write about what people imagine to be your self. And that self is not an imaginative, creative, artistic, or intellectual self.”

The writer of colour is thus trapped in a double bind. Racism must be investigated and challenged, but what does it mean if there is only one acceptable framework for addressing the issue? What does it mean if diversity initiatives laud only one kind of story?

This critical failure is exacerbated by industry demographics. According to a 2018 survey of Canadian publishing, 82 percent of the country’s publishing professionals are white. The scarcity of racialized people in positions of power—editorial and marketing being the true gatekeeping roles—means that few internal mechanisms exist to keep publishers accountable. Even Laferrière complains that, late into his career, he is still expected to be a spokesperson for the Black experience. “My publisher in Paris was interested by the way Caribbean and Creole writers treat the question of identity,” he tells Gollner. “I wasn’t at all interested in that. I wanted to approach the subject not at all from a perspective tied to colonialism or politics or the left or the right. I wanted to tackle it rather in a strictly linguistic sense.”

Working in the Bathtub revels in Laferrière’s contrarian nature—which includes his refusal to submit to expectations often placed on racialized writers. He shifts and paces in conversation, flipping from one point of view to another, thinking out loud while renouncing or celebrating earlier beliefs. “The idea of the senses,” he tells Gollner, “is what permitted me, as a writer, to not aim to produce a logical kind of literature based on rationality and intelligence, but rather to produce something that aimed to seduce, not to convince. The aim was for the reader to be encircled by these perfumes I’m trying to describe—in activating senses that aren’t logical—so that he or she drops the need to judge.”

We can see that strategy in the novels that constitute Laferrière’s “American autobiography,” a pioneering project that fuses cerebral intensity with vivid sensuality. His self-reflexive style allows him to interrogate the value of dreams, imagination, and storytelling while depicting his favourite motifs (cheap wine by the feet, the sun glancing on skin) until they produce new insights. As he tells Gollner and repeats in many novels, the single thread woven through his work is that he sees “no distinction between writing and real life.” Everything is part of imagination, and to limit the imagination is to limit freedom: the freedom to write whatever he considers most vital.

Laferrière’s mischievous decision to obscure the line between memoir and fiction draws attention to this freedom. As he writes in I Am a Japanese Writer, “That’s another thing I detest: authenticity.” Laferrière argues repeatedly that the first-person has become a burden for racialized writers, who are asked to use authenticity to satisfy readers who demand cultural reportage over imagination. This is why a statement like “I am a Japanese writer” is so seductive for him—it’s impossible to disprove; reality, he insists, is what we make it. The novel’s “I” responds to baffled critics, “My Japan is invented and concerns only me.” And, “I’ll create something, then I’ll believe in it afterwards.” Or, when describing the influence of Japanese poet Basho, he writes, “The inventory of my inner landscape [is] provided by a vagabond poet.” By insisting that his imagination is as real as his experience, Laferrière casts off the expectations placed on writers of colour.

Laferrière addresses these expectations brilliantly and provocatively in Why Must a Black Writer Write about Sex? “Forget about racism,” he writes, “it’s not your business. It’ll burn the heart right out of you. We’re better off leaving racism to the racists. It’s a sickness, and they have to try and wipe it off the face of the planet themselves. You can’t be both the sickness and the cure. Don’t worry about it. If you do, you won’t have time for anything else.” Laferrière evades the concern he is supposed to be examining—simultaneously stating its importance while acknowledging that life is bigger and brighter and that it is not the responsibility of racialized people to provide the antidote to racial animosity.

Why Must a Black Writer Write about Sex? was published in 1994. Nearly three decades later, little has changed. Antiracist reading lists have increased in popularity, directing readers toward the work of racialized writers not out of a desire to engage with style but as a treatment for intolerance.

Laferrière’s books have yet to find an easy home with English readers, but he has done much to show a way forward. In Working in the Bathtub, Gollner presents a writer who has carved out a unique path by insisting on his own happiness, playfulness, and lyrical impulses. By writing formally challenging, thematically bold works, Laferrière demands to be read on his own terms. He is tired, he bluntly tells Gollner, “of being seen as a Caribbean writer, as a Québécois writer, as an ethnic writer, as an exiled writer—instead of just simply as a writer.”